Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

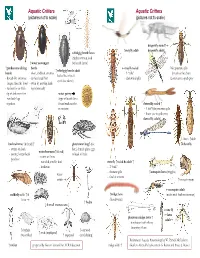

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Yellow Mayfly (Potamanthus Luteus )

SPECIES MANAGEMENT SHEET Yellow mayfly (Potamanthus luteus ) The Yellow mayfly is one of Britain’s rarest mayflies. The nymphs or larvae of this mayfly typically live in silt trapped amongst stones on the riverbed in pools and margins and grow to between 15 and 17mm. They are streamlined with seven pairs of thick feathery gills that are held outwards from their sides. The adults have three tails and large hindwings. The body is a dull yellowish-orange with a distinctive broad yellowish brown stripe along the back. The wings are yellow and the cross-veins are a dark reddish colour. Due to its rarity and decline in numbers this insect has been made a Priority Species on the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP). Life cycle There is one generation of this mayfly a year which overwinters as larvae. The adult mayflies are short lived and emerge between May and late October (with peak emergence in July). They will typically emerge at dusk and usually from the surface of the water, although they may also emerge by climbing up stones or plant stems partially or entirely out of water. Distribution map This mayfly is historically a rare species with populations in the River Wye and Usk, Herefordshire. The most recent surveys show a dramatic decline in the River Wye population and have failed to find this species in the River Usk. A small population has however recently been found in the River Teme in Worcestershire. Habitat In the Herefordshire streams where this species has been found, the larvae have been found under loose stones, preferring mobile sections of shingle or a mixture of larger stones with loose shingle such as those found downstream of bridges or at the confluence of tributaries. -

Insects Carolina Mantis Mayfly

I l l i n o i s Insects Carolina mantis mayfly elephant stag beetle widow skimmer ichneumon wasp click beetle black locust borer birdwing grasshopper large milkweed bug (adults and nymphs) mantisfly walking stick lady beetle stink bug crane fly stonefly (nymph) horse fly wheel bug bot fly prairie cicada leafhopper robber fly katydid alderfly syrphid fly Order Ephemeroptera mayfly Species List Order Coleoptera black locust borer click beetle This poster was made possible by: nsects and their relatives (arthropods) make up nearly 80 percent of the known animal species. Scientists elephant stag beetle lady beetle Illinois Department of Natural Resources Order Plecoptera stonefly currently estimate that 5 to 15 million species of insects exist. In contrast, 5,000 species of mammals are Order Orthoptera birdwing grasshopper Carolina mantis Division of Education found on our planet. In Illinois, we have more than 20,000 species of insects, and many more likely katydid Illinois Natural History Survey I Order Hemiptera large milkweed bug Illinois State Museum occur, as yet undetected in our state! The scientific study of insects is known as entomology. Entomologists stink bug wheel bug Order Diptera bot fly study insects for many reasons, including their incredible number of species and their wide variety of sizes, crane fly horse fly colors, shapes, and lifestyles. The 24 species depicted on this poster were selected by Michael R. Jeffords of robber fly syrphid fly Order Homoptera leafhopper the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Illinois Natural History Survey, to represent the variety of prairie cicada Order Phasmida walking stick insects occurring in our state. -

Aquatic Insects

Volume 33 | Issue 8 April 2020 Aquatic Insects Photo CCBY Rhonda Clements on Flickr. Inside: Aquatic Insects Constructing Caddisflies Toothed Dragon Marvelous Mayflies Nature's Red Flags Be Outside - Fishing is Fun idfg.idaho.gov Aquatic Insects Aquatic insects have some things in common with all insects. They have six legs. They have no bones but are covered by an exoskeleton, a shell similar to your fingernails. They also have three main parts to their body: head, thorax and abdomen. To be called aquatic insects, insects must spend part of their lives in water. They may live beneath the water surface or skim along the top. Some examples of aquatic insects are mosquitoes, dragonflies and caddisflies. Aquatic insects come in many shapes and sizes, and they all have some interesting ways of dealing with living in and on water. If you were an insect living underwater, how would you breathe? Insects are animals, so they need oxygen to survive. Many aquatic insects have gills, just like fish. The gills may be attached to the outside of the insect’s body or found inside the body. Some insects have tubes sticking out of their abdomens. They stick the tube above the water and breathe the same air you breathe. They may even stick the tube into plants underwater. They get oxygen straight from the plants that make it! Other aquatic insects, like diving beetles, grab bubbles of air and pull them underwater. The beetles carry the bubble in their back legs as they swim. Once they have used all the air in the bubble, they go up and grab another bubble. -

Declines in an Abundant Aquatic Insect, the Burrowing Mayfly, Across

Declines in an abundant aquatic insect, the burrowing mayfly, across major North American waterways Phillip M. Stepaniana,b,c,1 , Sally A. Entrekind, Charlotte E. Wainwrightc , Djordje Mirkovice , Jennifer L. Tankf , and Jeffrey F. Kellya,b aDepartment of Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019; bCorix Plains Institute, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019; cDepartment of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556; dDepartment of Entomology, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24060; eCooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072; and fDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556 Edited by David W. Schindler, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, and approved December 12, 2019 (received for review August 6, 2019) Seasonal animal movement among disparate habitats is a fun- while also serving as a perennial annoyance for waterside resi- damental mechanism by which energy, nutrients, and biomass dents; most of all, these mayfly emergences were a conspicuous are transported across ecotones. A dramatic example of such sign of a productive, functional aquatic ecosystem (14–17). How- exchange is the annual emergence of mayfly swarms from fresh- ever, by 1970, these mass emergences had largely disappeared. water benthic habitats, but their characterization at macroscales The combination of increasing eutrophication from agricultural has remained impossible. We analyzed radar observations of runoff, chronic hypoxia, hydrologic engineering, and environ- mayfly emergence flights to quantify long-term changes in annual mental toxicity resulted in the disappearance of Hexagenia from biomass transport along the Upper Mississippi River and West- many prominent midwestern waterways, with complete extir- ern Lake Erie Basin. -

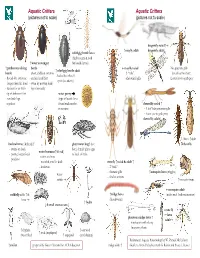

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny - row back legs (type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery buoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Dichotomous Key to Orders

FRST 307 Introduction to Entomology KEY TO COMMON INSECT ORDERS What is a Key? In biological sciences a “key” is a written tool used to determine the taxonomic identification of plants, animals, soils, etc. For this lab, a key will be used to identify insects to Order. More detailed identifications to family, genus and species are beyond the scope of this course, but can be accomplished using appropriate guides available from the library. Taking a Closer Look Because insects are so small, differentiating among species, families and even orders is often difficult. However, examination beneath a hand lens or microscope will allow you to see many of the characters mentioned in the key. Why Use a Key? Sometimes, you can identify an insect quickly by comparing it to pictures in field guides or on the internet. Pictures are a great tool, but the use of a key is essential to guarantee that your identification is accurate. Why? Because some insects, even ones from separate orders, can look almost exactly alike. For example, many flies (order Diptera) look almost exactly like wasps (order Hymenoptera). Using your key, you will find that a fly has 1 pair of wings, whereas wasps have 2 pairs of wings. Key to Adult Insects Only Remember - immature insects and adult insects are often very different. This is especially true for holometabolous (complete metamorphosis) insects where the immature stages are larvae and pupae. The key included in this guide is only useful for keying adult insects to order. Also, this key does not cover other creatures related to insects, like spiders, sowbugs, and centipedes. -

The Mayfly Newsletter

The Mayfly Newsletter Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 1 3-1-2012 The Mayfly Newsletter Peter M. Grant Southwestern Oklahoma State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mayfly Recommended Citation Grant, Peter M. (2012) "The Mayfly Newsletter," The Mayfly Newsletter: Vol. 17 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mayfly/vol17/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Newsletters at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Mayfly Newsletter by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The MAYFLY NEWSLETTER Vol. 17 No. 1 Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford, Oklahoma 73096-3098 USA March 2012 News from the Permanent Committee Dear Mayfly Students and Enthusiasts, The year 2011 comes to an end and, needless to say, it has been a peculiar year. We should have met this spring in Kiyosato for our joint meeting with Plecopterists. The tragic events which happened in March in Japan prevented finally the organization of such a meeting. Our sincere thoughts and thanks are addressed to our Japanese colleagues for the hard work to rapidly relocate the conference site and their willing to host the congress in 2012. The next Joint International Conference will be held in Wakayama City, Wakayama Prefecture, Kansai District, Japan, 3-9 June 2012. The preliminary program includes welcome and farewell parties and a mid-conference barbeque party and excursion. The deadline for registration and abstract submission is 30 March. -

Aquatic Insects

Aquatic Insects D-BAIT Lesson Purdue Polytechnic Institute Purdue Dept. of Entomology Photo credit: John Obermeyer, Purdue University Entomology What is an Insect? 1 Insects are: 2 1) Animals which are heterotrophs with internal digestion 3 2) Arthropods, which have an exoskeleton with jointed legs 3) Insects have external mouthparts, three body regions, and six legs https://cals.arizona.edu/pubs/garden/mg/entomology/intro.html • 3 Insect Body Sections: – Head: sensory & feeding – Thorax: movement, legs & wings – Abdomen: reproduction, digestion Aquatic Insect Evolution • All aquatic insects have wings as adults • Primitive “old-winged” insects: mayflies & dragonflies • “New-winged” insects derived folding before metamorphosis evolved: wings stoneflies, true bugs wings • Most recently evolved groups have new folding wings and metamorphosis: flies, beetles, caddisflies, net-winged insects Insect Life Cycles Incomplete metamorphosis Complete metamorphosis - get larger at each molt - immature and adult very different - wing buds appear and increase - wings visibly absent until adult - adult can be aquatic or terrestrial - adult can be aquatic or terrestrial Habitats & Challenges • Habitat is the ecological area inhabited by a species that provides it with nutrition, shelter, and the ability to reproduce (mates, nesting sites, etc…) • Each habitat type presents different benefits and challenges to species Ponds and Lakes Streams and Rivers - Often full of plants - Moving water - Low oxygen content - Higher oxygen content Life in the River -

How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them

insects Perspective Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them Natalie E. Duffus , Craig R. Christie and Juliano Morimoto * School of Biological Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Zoology Building, Tillydrone Ave, Aberdeen AB24 2TZ, UK; [email protected] (N.E.D.); [email protected] (C.R.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Insects—as many other organisms—provide services for our societies, which are essential for our sustainable future. A classic example of an insect service is pollination, without which food production collapses. To date, though, there has often been a generalised misconception about the benefits of insects to our societies, and misunderstandings on how insects have revolutionised our cultures and thus our lives. This misunderstanding likely underpins the general avoidance, disregard for, or even deliberate attempts to exterminate insects from our daily lives. In this Perspective, we provide a different viewpoint, and highlight the key areas in which insects have changed our cultures, from culinary traditions to architecture to fashion and beyond. We then propose a general framework to help portray insects—and their benefits to our societies—under a positive light, and argue that this can help with long-term changes in people’s attitude towards insects. This change will in turn contribute to more appropriate conservation efforts aimed to protect insect biodiversity and the services it provides. Therefore, our ultimate goal in the paper is to raise awareness of the intricate and wonderful cultural relationships between people and insects that are fundamental to our long-term survival in our changing world. -

September Fly Fishing Reports By: Weston Niep Pattern: Matt's Hi-Vis Spinner Summer Fishing Will Be Gone As Soon As It Came

September Fly Fishing Reports By: Weston Niep Pattern: Matt's Hi-Vis Spinner Summer fishing will be gone as soon as it came. Family Matched: Mayflies However, we still have a few weeks to say our Species Matched: Trico Mayfly goodbyes. I highly recommend getting out over the Life Cycle Matched: Spawned Out Spinner coming weeks as the dry fly depression will kick in before you think. Flows across the state have During a recent visit to Grand Junction, I made a de- dropped significantly causing fish to accumulate in tour into Montrose to visit the offices of Ross Reels. I certain holes. Now is your last good chance to ham- mer the freestones before winter sends us all to had the pleasure of meeting the team and touring the the midge rich tail-waters. Get out there and plant where the fly reels are manufactured. These drown some flies! reels have been recognized as one of the most innova- tive, dependable and best performing in the world. It Cache la Poudre- 147 cfs at Canyon Mouth was a pleasure to spend time with these folks and see The tiny moving water mayfly family Flows have dropped significantly over the past their engineering processes. If you find yourself fishing of Tricorythodes or more commonly known as Tri- month. This in combination with the unseasonably cos make up what for what they lack in size warm weather has led to some unbelievable fish- the waters of the western slope, you should stop by (generally sizes 18-22) with their almost plague-like ing. -

Bug's Eye View No 11 Mayfly

Bug's Eye View No 11 Mayfly https://mailchi.mp/35985f7de714/bugs-eye-view-no-11-mayfly?e... Subscribe Past Issues Translate No 11 May 15, 2018 View this email in your browser Mayfly Various species Order: Ephemeroptera Contrary to popular conception, mayflies are relatively long-lived insects. While it is true that adult mayflies do not feed and only live a day or two—just long enough to mate and lay eggs, most mayflies have an annual life cycle, which means that most adult mayflies are about one year old when they die. That’s pretty old for an insect, and a few species take several years to develop from egg to adult. Mayfly taxonomy and identification is pretty complex. Worldwide there are thousands of species, representing dozens of families. Immature mayflies, known as naiads, live in the water, where they feed on algae and other organic materials and breath by absorbing oxygen through their skin and abdominal tracheal gills. When mature, they move to the surface of the water to emerge, and the non-feeding adults spend a day or two mating and laying eggs to repeat the cycle. Like periodic cicadas, adult mayflies tend to emerge en masse, so fish, birds and other predators can’t eat them all before they have a chance to mate and lay eggs. Numbers can be huge, millions and millions, and heavy emergences of mayflies show up clearly on weather radar—like a light to moderate thunderstorm. Some summers the number of mayflies around the Ross Barnett Reservoir and other large lakes is so high they cause safety hazards, general consternation and other problems by accumulating on walkways, roads and buildings.