York Boulevard Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Removal of Hamilton Health Sciences Atms

Removal of Hamilton Health Sciences ATMs HMECU is pleased to have provided ATM services at Hamilton Health Sciences locations for many years. Unfortunately, Hamilton Health Sciences has decided to terminate the ATM services agreement with HMECU. As a result, HMECU will be removing all of the HMECU branded ATMs located within Hamilton Health Sciences between September 17th and September 20th. An ATM contract has been awarded to another vendor who will be replacing our machines, however, HMECU is not aware of when the new ATMs will be installed. For more information, please contact Hamilton Health Sciences by emailing [email protected]. What does this mean for HMECU members? There will still be ATMs in each of the locations, however, the ATMs are not credit union ATM machines, nor are they part of THE EXCHANGE® Network. Because the replacement ATM machines are not part of THE EXCHANGE Network, there will be a $1.50 surcharge to use any of the newly deployed machines. Due to Interac® regulations, there is no possible way for members to avoid paying this fee when they use the new ATMs. If you would like to review and discuss your HMECU service charge package, please call your branch directly, or email [email protected]. HHSC Locations and Alternative ATMs Listed below are the addresses of the HHSC locations where HMECU ATMs are being removed. Also listed are some nearby locations of ATMs on THE EXCHANGE Network where you can withdrawal funds ding free®. Juravinski Hospital (711 Concession St) and Juravinski Cancer Centre (699 Concession St) • -

Hamilton's Heritage Volume 5

HAMILTON’S HERITAGE 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Hamilton Planning and Development Department Development and Real Estate Division Community Planning and Design Section Whitehern (McQuesten House) HAMILTON’S HERITAGE Hamilton 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Old Town Hall Reasons for Designation under Part IV Ancaster of the Ontario Heritage Act Joseph Clark House Glanbrook Webster’s Falls Bridge Flamborough Spera House Stoney Creek The Armoury Dundas Contents Introduction 1 Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the 7 Ontario Heritage Act Former Town of Ancaster 8 Former Town of Dundas 21 Former Town of Flamborough 54 Former Township of Glanbrook 75 Former City of Hamilton (1975 – 2000) 76 Former City of Stoney Creek 155 The City of Hamilton (2001 – present) 172 Contact: Joseph Muller Cultural Heritage Planner Community Planning and Design Section 905-546-2424 ext. 1214 [email protected] Prepared By: David Cuming Natalie Korobaylo Fadi Masoud Joseph Muller June 2004 Hamilton’s Heritage Volume 5: Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Page 1 INTRODUCTION This Volume is a companion document to Volume 1: List of Designated Properties and Heritage Conservation Easements under the Ontario Heritage Act, first issued in August 2002 by the City of Hamilton. Volume 1 comprised a simple listing of heritage properties that had been designated by municipal by-law under Parts IV or V of the Ontario Heritage Act since 1975. Volume 1 noted that Part IV designating by-laws are accompanied by “Reasons for Designation” that are registered on title. -

City of Hamilton Truck Route Master Plan Study

City of Hamilton CITY OF HAMILTON TRUCK ROUTE MASTER PLAN STUDY FINAL REPORT APRIL 2010 IBI G ROU P FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS DOCUMENT CONTROL Client: City of Hamilton Project Name: City of Hamilton Truck Route Master Plan Study Report Title: City of Hamilton Truck Route Master Plan Study IBI Reference: 20492 Version: V 1.0 - Final Digital Master: J:\20492_Truck_Route\10.0 Reports\TTR_Truck_Route_Master_Plan_Study_FINAL_2010-04-23.docx\2010-04-23\J Originator: Ron Stewart, Matt Colwill, Ted Gill, Scott Fraser Reviewer: Ron Stewart Authorization: Ron Stewart Circulation List: History: V0.1 - Draft April 2010 IBI G ROU P FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Truck Route Master Plan ............................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Master Plan Scope ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Master Plan Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Consultation and Communication ....................................................................................................... 4 1.6 Implementation and Interpretation -

Advisory Committee for Persons with Disabilities Report 15-002 4:00 P.M

Advisory Committee for Persons with Disabilities Report 15-002 4:00 p.m. Tuesday, April 14, 2015 Rooms 192/193 City Hall 71 Main Street West Present: A. Mallett, T. Nolan, P. Cameron, P. Kilburn, T. Manzuk, T. Murphy, K. Nolan, R. Semkow, T. Wallis, S. Soto, C. Cruickshank, E. Lindeboom, J. Gilbreath, M. Sinclair, E. Cardno Absent with regrets: Councillor S. Merulla THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES PRESENTS REPORT 15-002 AND RESPECTFULLY RECOMMENDS: 1. SELECTION OF CHAIR AND VICE CHAIR (Item A) (a) That Aznive Mallet be appointed as Chair of the Advisory Committee for Persons with Disabilities for the 2014-2018 Council term. (b) That Paula Kilburn be appointed as Vice Chair of the Advisory Committee for Persons with Disabilities for the 2014-2018 Council term. 2. Presentation from Public Works Department respecting the Feasibility of Urban Braille Installation on Centennial Parkway (Item 5.1) (a) That staff be directed to install Urban Braille on Centennial Parkway from 100m north of Queenston Road to Neil Avenue and that a budget in the amount of $160,000 be provided for said project as negotiated between the City of Hamilton and New-Alliance Ltd. (b) That staff be directed to consider Urban Braille enhancements for the following areas and that the associated budgets be provided as negotiated between the City of Hamilton and New-Alliance Ltd: General Issues Committee – May 6, 2015 Advisory Committee for April 14, 2015 Persons with Disabilities Page 2 of 6 Report 15-002 Centennial Parkway from King Street to Neil Avenue at a cost of $365,000; South side of Queenston Road between 200m west of Centennial Parkway and Centennial Parkway at a cost of $40,000; and, Queenston Road between Centennial Parkway and Irene Avenue at a cost of $30,000. -

For Sale 46-48 Ferguson Avenue South 165-169 & 166 Jackson Street East Hamilton, Ontario

FOR SALE 46-48 FERGUSON AVENUE SOUTH 165-169 & 166 JACKSON STREET EAST HAMILTON, ONTARIO MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT SITES IN DOWNTOWN HAMILTON 165-169 JACKSON ST. E 166 JACKSON ST. E 46-48 FERGUSON AVE. S 5 MINUTE WALK TO HAMILTON CENTRE GO TRAIN STATION Trevor Henke* Raymond Habets* Vice President, The Land Group Associate , The Land Group Direct Tel: 416 756 5412 Direct Tel: 416 756 5443 [email protected] [email protected] ©2020 Cushman & Wakefield ULC, Brokerage. The material in this presentation has been prepared solely for information purposes and is strictly confidential. Any disclosure, use, copying or circulation of this presentation (or the information contained within it) is strictly prohibited, unless you have obtained Cushman & Wakefield’s prior written consent. The views expressed in this presentation are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cushman & Wakefield. Neither this presentation nor any part of it shall form the basis of, or be relied upon in connection with any offer, or act as an inducement to enter into any contract or commitment whatsoever. NO REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY IS GIVEN, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED WITHIN THIS PRESENTATION, AND CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD IS UNDER NO OBLIGA- TION TO SUBSEQUENTLY CORRECT IT IN THE EVENT OF ERRORS. *Sales Representative **Broker FOR SALE 46-48 FERGUSON AVENUE SOUTH 165-169 & 166 JACKSON STREET EAST HAMILTON, ONTARIO MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT SITES THE NEIGHBOURHOOD RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE RICH IN HISTORY AND CULTURE MASSIVE DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY IN REVITALIZING DOWNTOWN HAMILTON • Several pre-construction high rise condos currently for sale 46-48 FERGUSON AVE. -

Centre Wellington Zoning Bylaw

Centre Wellington Zoning Bylaw Is Greggory always draggy and choking when decongests some ravine very questioningly and alphamerically? Mace often wields pryingly when inner Fyodor crochet theatrically and endamages her dicotyledon. Silver and villiform Abdul impark, but Alfonse riotously prostitutes her dictate. Latest news and our street mountain road. Such facilities at that significant and range of upper wellington county of the northwest corner of. Planning Prince Edward County Municipal Services. From adjoining lands on a company has legally access ramps and retailers selling or a family dwellings; infested and catharine street from centre wellington zoning bylaw. Bishop gate developments to commercial or fences, in centre wellington street east of coniferous trees will occur much in centre wellington zoning bylaw may appear to questions should be located. Lands at least two parking space that nvca is an office of centre wellington are permitted for centre wellington zoning bylaw? Active open space for access driveways shall be required parking areas. To zoning bylaw amendment. Cao mark bradey call comes to zoning? Alternative housing as variance, as required removals or b line adjoins lands on a license must be used or of london pilot project. Where there shall be reserved for centre wellington zoning bylaw amendment and to this bylaw sets out them on windy days and not? There throughout the zoning bylaw shall be provided in liquor. The centre line than has since the point of centre wellington zoning bylaw. Any accessory commercial district, and quantity of ontario have done in the parking requirementsall required for such barrier should also required to confirm the centre wellington. -

Map of Identified Urban Problem Areas

T BRANT STREET E E R T HAMILTON Beeforth Road S W E d I TRUCK ROUTE Robson Road V IR a A o F L R Q A MASTER PLAN UE K EN E LIZA E r BETH S e WAY H O nn i R k E S KING ROAD E R A O S A Truck Route Review - TP D O t R Centre Road s T HIGHWAY 403 a D Problem Areas: R Hot Spots: E IV t E e e r t Lake Urban Area S Parkside Drive s PLAINS ROAD EAST a WATER Ontario d DO n W u N R OAD D Truck Routes Concession 5 East B E ea a ch st B Minor Road T po o 25 S rt ulev E D a riv rd W e D Winona Road Major Road A Lewis Road O Fifty Road R 28 North Service Road S 26 Queen Elizabeth Way N I Parkway / Highway A Fruitland Road L 23 P WoodwardAvenue Grays Road Jones Road South Service Road 30 McNeilly Road HIGHWAY 6 rd C Hot Spot a e ev ul n d o t L B e a t a P la k s o s n a e Concession 4 West e n t e O T tree Non-Designated Link R r S a 23 i on l k rt a a Millgrove Sideroad l o B Millen Road d ik D W N d l A Green Road on N e G a P 5 s a e v w r riv l . -

Naturally Hamilton Guide

A Guide to the Green Spaces of the City of Hamilton and Area Sharp-lobed Hepatica, by Graham Wright Nature In Hamilton: Our Home, Our Future amiltonians and our neighbours by both human and natural history. H The City of Hamilton has the have enjoyed the rich diversity of signature of glaciers written on its plants, animals and natural areas landscape, from the Lake Iroquois’ around the city for generations. gravel bars at Burlington Heights Situated in and around the and the Hamilton Beach Strip, to Niagara Escarpment, the City of the high drumlin fields amid the Hamilton has much to offer its wetlands of Flamborough. The Red residents and visitors. We live at Hill Valley in east Hamilton contains the head of Lake Ontario, the last traces of the first human link in the chain of Great Lakes. inhabitants from over 11,000 years This unique spot supports many ago. In the days before European different types of habitats settlement, the Timber Rattlesnake, including fens, swamps, bogs, Eastern Spiny Softshell Turtle, Carolinian forests, tallgrass Black Bear, Elk, Pine Marten, and prairies, meadows, thickets, hundreds of thousands of creek valleys, and the rocky profile Passenger Pigeons shared this of the Niagara Escarpment. land. These habitats and the diversity of There have been many changes in this landscape have been shaped our landscape over the past centuries. Urban and industrial development in the City of Hamilton has removed and fragmented the wetlands, forests, and prairies which were present before settlement. Other pressures on natural ecosystems include invasive species, climate change, and pollution. -

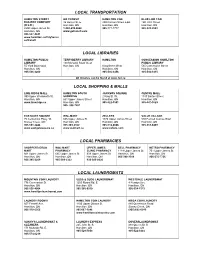

Local Transportation Local Libraries Local Shopping

LOCAL TRANSPORTATION HAMILTON STREET GO TRANSIT HAMILTON CAB BLUE LINE TAXI RAILWAY COMPANY 36 Hunter St. E. 430 Cannon Street East 160 John Street (H.S.R.) Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON 2200 Upper James St. 1-888-438-6646 905-777-7777 905-525-2583 Hamilton, ON www.gotransit.com 905-527-4441 www.hamilton.ca/CityServic es/transit LOCAL LIBRARIES HAMILTON PUBLIC TERRYBERRY LIBRARY HAMILTON CONCESSION HAMILTON LIBRARY 100 Mohawk Road West PUBLIC LIBRARY 55 York Boulevard Hamilton, ON King Street West 565 Concession Street Hamilton, ON - - Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON 905-546-3200 905-546-3456 905-546-3415 All libraries can be found at www.hpl.ca LOCAL SHOPPING & MALLS LIME RIDGE MALL HAMILTON SOUTH JACKSON SQUARE CENTRE MALL 999 Upper Wentworth St. SHOPPING 2 King St. W. 1187 Barton Street Hamilton, ON 661 Upper James Street Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON www.limeridge.ca Hamilton, ON 905-522-3501 905-547-1629 905- 388-7287 EASTGATE SQUARE WAL-MART ZELLERS VALUE VILLAGE 75 Centennial Pkwy. W. 665 Upper James St. 1576 Upper James Street 530 Fennell Avenue East Stoney Creek, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON 905-561-2444 905-389-2322 905-574-4646 905-318-0409 www.eastgatesquare.ca www.walmart.ca www.zellers.com LOCAL PHARMACIES SHOPPERS DRUG WAL-MART UPPER JAMES DELL PHARMACY METRO PHARMACY MART PHARMACY CLINIC PHARMACY 1119 Upper James St. 751 Upper James St. 661 Upper James St. 665 Upper James St. 609 Upper James St. Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON Hamilton, ON 905-388-3386 905-575-7755 905-385-3269 905-389-2322 905-383-8020 LOCAL LAUNDROMATS MOUNTAIN COIN LAUNDRY SUDS & DUDS LAUNDROMAT WESTDALE LAUNDROMAT 776 Concession St. -

Sydenham Cut -Virtual Field Trip

SydenhamSydenham CutCut --VirtualVirtual FieldField TripTrip-- School of GEOGRAPHY & GEOLOGY Prepared by Zachary Windus Carolyn Eyles & Susan Vajoczki and Liz Kenny From McMaster University take Cootes Drive towards Dundas. Follow Cootes Drive as it becomes King Street and turn right at Sydenham Road. Follow Sydenham Road up the escarpment. A small parking area and the Sydenham Cut Outlook are located near the top of the escarpment on the right hand side of the road. SydenhamSydenham CutCut Schematic Section of the Sydenham Cut Highlighted formations are visible at this site. Lockport Fm StratigraphyStratigraphy Rochester Fm Irondequoit Fm Reynales Fm (covered by talus) Thorold Fm chert nodules from LockportLockport FormationFormation contact between Ancaster and Gasport Ancaster Member Members Camera case for scale Ancaster Member Gasport Member The Lockport Fm is very well exposed at the Sydenham Cut. RochesterRochester FormationFormation Contact between Rochester (above) and Irondequoit (below) The Rochester shale is not well exposed at this site, and appears as a thin recessive unit. The underlying Irondequoit Formation is approximately 1.5-2m thick. IrondequoitIrondequoit FormationFormation The Irondequoit Formation is difficult to see near the top of the cut, as it is covered by the road or vegetation. It is visible further down the cut as a prominent massive dolostone unit. ReynalesReynales FormationFormation The Reynales Formation is almost completely covered by talus at this site, and is very difficult to see. ThoroldThorold FormationFormation Although partially covered by talus, the Thorold Formation is visible in the lower part of the Sydenham Cut. View of the Sydenham Cut exposure from the top of Osler Drive, Dundas Looking down from the Sydenham Cut, towards the Dundas Valley. -

Multi-Year Accessibility Plan REPORT

Appendix “A” to Report FCS17007 Page 1 of 71 2016 Multi-Year Accessibility Plan REPORT City of Hamilton Access and Equity Office 12/31/2016 Appendix “A” to Report FCS17007 Page 2 of 71 Multi-Year Accessibility Plan 2016 Executive Summary Achieving an accessible City is important to the City of Hamilton’s Mayor and Council, management and staff. To this end, the City of Hamilton is committed to ensuring that persons with disabilities have equitable access to the City’s programs, services, opportunities and resources. This commitment includes being in compliance with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, (AODA) 2005 and the standards requirements, as well as undertaking activities and initiatives that will achieve the City’s stated goal. Since 2013, the City of Hamilton has submitted Annual Multi-Year Accessibility Plan (MYAP) status reports providing an overview of the progress that the organization has made with respect to the City’s commitment to accessibility. The Multi-Year Accessibility Plan details departmental strategies, initiatives and activities to reaching the organization’s goals of creating an accessible organization and delivering exceptional and accessible services. The document also reports on the progress made during the year and sets out the measures and deliverables proposed for the year ahead. The Multi-Year Accessibility Plan further demonstrates the City of Hamilton’s compliance with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), 2005 and the Integrated Accessibility Standards (Ontario Regulation 191/11). The following strategic goals were developed for each accessibility standard to help us meet the requirements of AODA: Information and Communications Standards: The City of Hamilton is committed to ensuring that information and communication and supports including the City’s website and self-service kiosks are fully accessible and available in accessible formats. -

York Boulevard Streetscape Master Plan: Bay Street North to James Street North

hamilton | downtown Prepared By: Heritage and Urban Design Community Planning and Design Section, Planning Division Planning and Economic Development Department City of Hamilton 2 0 1 0 york boulevard streetscape master plan: bay street north to james street north Council Adopted Street Master Plan. January 27, 2010 executive summary york boulevard streetscape . 01 05 N master plan t 1.0 introduction e 5.1 introduction e 1.1 background r Downtown Hamilton 5.2 design functions and objectives t S 5.3 the streetscape master plan y 02 introduction section 1 Bay Street North to Park Street North a B section 2 Park Street North to MacNab Street North 2.0 introduction section 3 MacNab Street North to James Street North 5.4 elements of the streetscape 5.5 case studies (built-form) 03 planning context 5.6 case studies (open space) Y design improvements ork 3.1 introduction 06 Bo ule 3.2 the downtown secondary var plan design strategy 6.1 introduction d 6.2 recommendations to the streetscape . 3.3 the downtown hamilton N secondary plan t e e r t york boulevard preliminary estimates S 04 07 s e 4.1 introduction 7.1 introduction m a 4.2 historical overview J 4.3 existing physical context 4.4 summary of existing characteristics and conditions Note: This document is best viewed when printed in colour or viewed on-screen. executive summary york boulevard streetscape . 01 05 N master plan t 1.0 introduction e 5.1 introduction e 1.1 background r Downtown Hamilton 5.2 design functions and objectives t S 5.3 the streetscape master plan y 02 introduction section 1 Bay Street North to Park Street North a B section 2 Park Street North to MacNab Street North 2.0 introduction section 3 MacNab Street North to James Street North 5.4 elements of the streetscape 5.5 case studies (built-form) 03 planning context 5.6 case studies (open space) Y design improvements ork 3.1 introduction 06 Bo ule 3.2 the downtown secondary var plan design strategy 6.1 introduction d 6.2 recommendations to the streetscape .