Policy Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

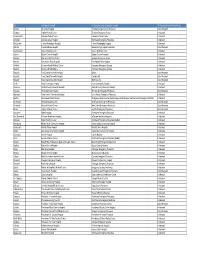

2005 Match Results by Name.Pdf

Table 1 The University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine 2005 Graduates Residency Match Name Program Hospital Abdulhamid, Mohamed Surgery-Preliminary SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY Abdulhamid, Mohamed Neurological Surgery SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY Alam, Shayan Internal Medicine Mayo Graduate School of Med, Scottsdale, AZ Anderson, Chiquitia Pediatrics Wayne State University/Detroit Medical Center, Detroit, MI Anderson, Matthew Internal Medicine University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA Angel, Michael Anesthesiology Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Rochester, MN Barker, Carrie Pediatrics University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Madison, WI Baum, Christian Transitional Gundersen Medical Foundation, La Crosse, WI Baum, Christian Dermatology University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA Beckett, Brooke Transitional Central Iowa Health System, Des Moines, IA Beckett, Brooke Radiology Diagnostic Oregon Health Sciences Univ, Portland, OR Belsare, Geeta Transitional St. Francis Hospital of Evanston, Evanston, IL Belsare, Geeta Ophthalmology University of Chicago Hospitals, Chicago, IL Berglund, Lisa Orthopaedic Surgery University of North Carolina Hospitals, Chapel Hill, NC Bleeker, Jonathan Internal Medicine University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Bogle, Angela Emergency Medicine Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA Bormann, Kurt Orthopaedic Surgery Creighton/Nebraska Health Foundation, Omaha, NE Brady, Megan Orthopaedic Surgery Indiana University School of Medicine, -

Department of Radiology STAFF RADIOLOGISTS “The Best Interest of the Patient Is the Only Interest to Be Considered.” –William J

Department of Radiology STAFF RADIOLOGISTS “The best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered.” –William J. Mayo MAYO CLINIC IN ARIZONA Department Chair Akira Kawashima, M.D., Ph.D. Medical School: Kagoshima University Amy K. Hara, M.D. (Department Chair) Residency: Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Medical School: University of Missouri-Kansas City Center at Houston, Kyushu University Residency: Diagnostic Radiology, Mayo Graduate School Fellowship: Cross Sectional Body Imaging, of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN The Johns Hopkins University Fellowship: Abdominal Imaging, Mallinckrodt Institute of Certifications: American Board of Radiology Radiology, St. Louis, MO Academic Rank: Professor of Radiology Certifications: American Board of Radiology Interests: Genitourinary Radiology Academic Rank: Professor of Radiology Interests: Virtual Colonoscopy (CT Colonography), CT Christine O. (Cooky) Menias, M.D. Enterography, Crohn’s, GI Radiology, (CT/MRI), Reduced Medical School: George Washington University School of Radiation Dose CT, Radiology Informatics Medicine, Washington, D.C. Residency: Diagnostic Radiology, Mallinckrodt Institute of Abdominal Imaging Radiology, St. Louis, MO Fellowship: Abdominal Imaging, Mallinckrodt Institute of Kumaresan Sandrasegaran, M.B., Ch.B. Radiology, St. Louis, MO, (Division Chair) Certifications: American Board of Radiology and National Medical School: Godfrey Huggins School of Medicine, Board of Medical Examiners University of Zimbabwe Academic Rank: Professor of Radiology -

Association of American Medical Colleges and the Association of Hospital Medical Education

association of american medical colleges MEETING SCHEDULE COUNCIL OF TEACHING HOSPITALS ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD June 29-30, 1983 Washington Hilton Hotel permission WEDNESDAY, June 29, 1983 without 6:30pm COTH ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD MEETING Chevy Chase Room reproduced 8:00pm COTH ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD DINNER be Dupont Room to Not THURSDAY, June 30, 1983 AAMC 9:00am COTH ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD MEETING Farragut Room the of 1:00pm JOINT ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD LUNCHEON Monroe West 2:30pm EXECUTIVE COUNCIL BUSINESS MEETING collections Monroe East the from Document One Dupont Circle, N.W./Washington, D.C. 200381(202) 828-0400 AGENDA COUNCIL OF TEACHING HOSPITALS ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD MEETING June 30, 1983 Washington Hilton Hotel 9:00am-1:00pm I. Call to Order Consideration of Minutes Page 1 permission III. COTH Membership without A. Staff Report Page 10 B. Membership Applications Page 28 reproduced o Baptist Medical Centers Page 29 be Birmingham, Alabama to Not o The Germantown Hospital Page 36 and Medical Center Philadelphia, Pennsylvania AAMC St. Joseph Medical Center Page 49 the o of Wichita, Kansas IV. Department of Teaching Hospitals Activities Page 57 and Initiatives collections V. Review of 1983 COTH Spring Meeting Page 62 the from VI. Payment for Physician Services in a Executive Council Teaching Setting Agenda - page 18 VII. Plan of Action for Dealing with PGY-2 Executive Council Document Match Issues Agenda - page 56 VIII. ECFMG Constitutional Issues Executive Council Agenda - page 60 IX. Loan Forgiveness for Physicians in Executive Council Research Careers Agenda - page 68 X. Statement of Principles on NIH Executive Council Agenda - page 78 XI. Adjournment Association of American Medical Colleges COTH Administrative Board Meeting April 21, 1983 PRESENT Earl J. -

WA ER Physicians Group Directory Listing.Xlsx

City In-Network Hospital ER Physician group serving the hospital ER Physician Group Network Status Tacoma Allenmore Hospital Tacoma Emergency Care Physicians Out of Network Olympia Capital Medical Center Thurston Emergency Group In-Network Leavenworth Cascade Medical Center Cascade Medical Center In-Network Arlington Cascade Valley Hospital Northwest Emergency Physicians In-Network Wenatchee Central Washington Hospital Central Washington Hospital In-Network Ephrata Columbia Basin Hospital Beezley Springs Inpatient Services Out of Network Grand Coulee Coulee Medical Center Coulee Medical Center In-Network Dayton Dayton General Hospital Dayton General Hospital In-Network Spokane Deaconess Medical Center Spokane Emergency Group In-Network Ritzville East Adams Rural Hospital East Adams Rural Hospital In-Network Kirkland EvergreenHealth Medical Center Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Monroe EvergreenHealth Monroe Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Barton Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital CompHealth Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Staff Care Inc. Out of Network Forks Forks Community Hospital Forks Community Hospital In-Network Pomeroy Garfield County Memorial Hospital Garfield County Memorial Hospital In-Network Puyallup Good Samaritan Hospital Mt. Rainier Emergency Physicians Out of Network Aberdeen Grays Harbor Community Hospital Grays Harbor Emergency Physicians In-Network Seattle Harborview Medical Center Emergency Department at Harborview and -

Virginia Mason Medical Center First Hill Campus

Virginia Mason Medical Center First Hill Campus Compiled Major Institution Master Plan This Compiled Major Institution Master Plan (MIMP) for the Virginia Mason Medical Center has been prepared by Virginia Mason, URS Corporation, SRG Partnership, Weinstein A+U, Makers Architecture & Urban Design and Steinbrueck Urban Strategies, for submittal to Seattle’s Depart- ment of Planning and Development in compliance with Seattle Municipal Code (SMC) 23.69.032 D, Development of a Master Plan. This Compiled MIMP for the Virginia Mason campus was created using the following regional plan- ning efforts and guidelines as guiding principles, policies and requirements: The Washington State Growth Management Act (originally adopted in 1990) and codified as RCW 36.70A City of Seattle Ordinance 120691, adopted December 17, 2001, enacting regulations for the location, uses, and size of Seattle Major Medical and Educational Institutions The City of Seattle Comprehensive Plan The City of Seattle Transportation Strategic Plan The First Hill Neighborhood Plan The City of Seattle Transit Master Plan The Blue Ring Center City Open Space Plan The City Parks and Recreation 2011 Development Plan The City of Seattle Bicycle Master Plan The City of Seattle Pedestrian Master Plan Puget Sound Regional Council’s VISION 2040 The Seattle City Council approved the MIMP on December 16, 2013. The Council’s Findings, Conclusion and Decision (Clerk File 311081) contains 64 conditions of approval (pages 15 to 29). The Council’s Findings, Conclusion and Decision are included in their entirety as Appendix F to this Compiled Master Plan. Future development of the Virginia Medical Center is subject to those conditions. -

WA ER Physicians Group Directory Listing 12312019.Xlsx

ER Physician group serving the ER Physician Group City In-Network Hospital hospital Network Status Olympia Capital Medical Center Thurston Emergency Group In-Network Leavenwort Cascade Medical Center Cascade Medical Center In-Network Arlington Cascade Valley Hospital Northwest Emergency Physicians In-Network Wenatchee Central Washington Hospital Central Washington Hospital In-Network Ephrata Columbia Basin Hospital Beezley Springs Inpatient Services Out of Network Grand Coulee Medical Center Coulee Medical Center In-Network Dayton Dayton General Hospital Dayton General Hospital In-Network Ritzville East Adams Rural Hospital East Adams Rural Hospital In-Network Kirkland EvergreenHealth Medical Center Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Monroe EvergreenHealth Monroe Evergreen Emergency Services In-Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Barton Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital CompHealth Out of Network Republic Ferry County Memorial Hospital Staff Care Inc. Out of Network Forks Forks Community Hospital Forks Community Hospital In-Network Pomeroy Garfield County Memorial Hospital Garfield County Memorial Hospital In-Network Aberdeen Grays Harbor Community Hospital Grays Harbor Emergency Physicians In-Network Emergency Department at Harborview and Harborview Medical Seattle Harborview Medical Center Center Emergency Medicine In-Network Bremerton Harrison Medical Center West Sound Emergency Physicians Out of Network Silverdale Harrison Medical Center West Sound Emergency Physicians Out of Network Burien Highline -

Virginia Mason Memorial President and CEO Russ Myers to Retire in Early 2020

Contact: Rebecca Teagarden, Memorial Communications, 509-577-5051 Embargoed until 10 a.m., Friday, July 26, 2019 Virginia Mason Memorial President and CEO Russ Myers to retire in early 2020 YAKIMA — After a career of more than 30 years of service at Virginia Mason Memorial, President and CEO Russ Myers will retire in early 2020. Russ began his career at the hospital originally known as Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital in 1989 as a management analyst. His innovative thinking, hard work and dedication earned him increased responsibility and promotions to Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, and then Senior Vice President in 2011. He has served as the President and CEO of Virginia Mason Memorial since January 2014. He began his health care career as a pharmacist in Chehalis, WA, after earning a pharmacy degree at Washington State University. He completed an Accredited Hospital Pharmacy Residency at Moses Cone Hospital in Greensboro, NC. After practicing for 10 years as a hospital pharmacist, Russ attended the University of Washington and completed a master’s degree in health administration in 1989. In his role as CEO, in collaboration with Memorial’s Board of Directors and senior leadership team, he led the decision-making process to affiliate and integrate with Virginia Mason Health System in Seattle. Russ is a leader in the Yakima community, and through his roles with the Washington State Hospital Association, he is highly regarded by hospital executives throughout the state. Earlier this year, Russ was honored with a Silver Award as the Outstanding Medical Center Executive Outside the Puget Sound Region at Seattle Business magazine’s annual Leaders in Health Care Awards event. -

Hunter John 2018 CV

CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL DATA Name: John G. Hunter, MD, FACS FRCS Edin(hon) Work Address: Senior Vice President and Chief Clinical Officer School of Medicine, Office of the Dean Oregon Health & Science University 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road Portland, Oregon 97239-3098 503-494-6055 tel 503-494-3400 fax 503-702-5445 mobile [email protected] Home Address: 2541 SW Montgomery Drive, Portland, OR 97201 Date/Place of Birth: January 12, 1955 / Hanover, New Hampshire Wife: Laura Shearer Hunter Children: Sarah Elizabeth Hunter (born September 14, 1989) Samuel Wilkinson Hunter (born October 28, 1994) Jillían Renėe Hunter (born July 15, 2001) Citizenship: United States EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Current: Executive Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Health System Kenneth A.J. Mackenzie Professor of Surgery Portland, Oregon Prior: Senior Vice President and Chief Clinical Officer, OHSU Chair, OHSU Practice Plan OHSU School of Medicine 2017 Executive Vice President and Dean of the School of Medicine (Interim) – OHSU 2016-2017 Chair, Department of Surgery – OHSU 2001-2016 Vice Chair of Surgery (Clinical) Emory University School of Medicine 1995-2001 Chief, Division of Gastrointestinal Surgery Emory University School of Medicine 1992 – 1998 Chief of Surgical Endoscopy Department of Surgery, University of Utah 1988-1992 John G. Hunter, M.D., F.A.C.S. John G. Hunter, M.D. Page 2 EDUCATION Baccalaureate Degree: Harvard College, B.A. cum laude, 1973-1977, English Advanced Degrees: University of Pennsylvania, M.D., -

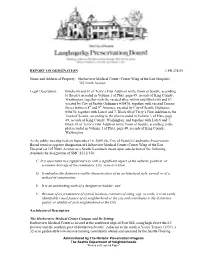

Harborview-Designation.Pdf

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 474/09 Name and Address of Property: Harborview Medical Center (Center Wing of the East Hospital) 325 Ninth Avenue Legal Description: Blocks 66 and 67 of Terry’s First Addition to the Town of Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 1 of Plats, page 49, records of King County, Washington; together with the vacated alley within said Blocks 66 and 67, vacated by City of Seattle Ordinance #58470; together with vacated Terrace Street between 8th and 9th Avenues, vacated by City of Seattle Ordinance #58470; together with Lots 6 and 7, Block 68 of Terry’s First Addition to the Town of Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 1 of Plats, page 49, records of King County, Washington; and together with Lots 6 and 7, Block 69 of Terry’s First Addition to the Town of Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 1 of Plats, page 49, records of King County, Washington. At the public meeting held on September 16, 2009, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of Harborview Medical Center (Center Wing of the East Hospital) at 325 Ninth Avenue as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standards for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction; E. -

Kyle Yasuda CV

CURRICULLUM VITAE Kyle E. Yasuda, MD January 2013 PERSONAL DATA Business Address: Box 359774 325 Ninth Avenue Seattle, WA 98104-2499 Telephone: (206) 744-9511 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION University of Washington School of Medicine, MD 1976-1980 University of Washington, Seattle BS in Chemistry with College Honors, Magna Cum Laude 1972-1976 POST GRADUATE TRAINING United States Public Health Service Primary Care Policy Fellow 2000 Pediatric Residency, University of Washington and Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center, Seattle, WA Program Director: William O. Robertson, MD 1981-1983 Pediatric Internship, University of Washington and Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center, Seattle, WA 1980-1981 FACULTY POSITIONS Clinical Professor, Department of Pediatrics University of Washington School of Medicine 2000-present College Faculty, University of Washington School of Medicine 2002-present HOSPITAL POSITIONS Pediatrician, Harborview Medical Center 2002-present EpicCare: liaison to Harborview Medical Center’s primary care Clinics 2012-present Pediatric Workgroup, Chair 2012-present Medical Director, The Pediatric Clinics Harborview Medical Center 2006-2011 Pediatrician, Virginia Mason Medical Center 1983-2002 Head, Section of Pediatrics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA 1988-2000 Director, Newborn Nursery, Virginia Mason Hospital, Seattle, WA 1984-1992 Neonatal Consultant, Virginia Mason Hospital, Seattle, WA 1983-1984 Pediatrician, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Seattle, WA 1983-1984 HONORS -

University of Mississippi School of Medicine 2013 Match Full Match

University of Mississippi School of Medicine 2013 Match Full Match Results 114 Students Mimi Abadie Sedrick Bradley Medicine‐Pediatrics Internal Medicine Georgetown University Hospital University of Mississippi Medical Center Washington, District of Columbia Jackson, Mississippi Caleb Adams Kimberly Bridges Orthopedic Surgery Internal Medicine University of Mississippi Medical Center University of Mississippi Medical Center Jackson, Mississippi Jackson, Mississippi Wesley Aldred Cherita Brown Internal Medicine Obstetrics‐Gynecology University of Mississippi Medical Center Methodist Health System Dallas Jackson, Mississippi Dallas, Texas Najat Al‐Sherri John Browning Obstetrics‐Gynecology Family Medicine Barnes‐Jewish Hospital University of Mississippi Medical Center St. Louis, Missouri Jackson, Mississippi Stephen Anderson Tyler Burns Internal Medicine Anesthesiology University of Mississippi Medical Center University of Arkansas Jackson, Mississippi Little Rock, Arkansas Christian Barnes Taylor Burns Otolaryngology Psychiatry University of California Irvine Med. Center Albert Einstein/Beth Israel Medical Center Orange, California New York, New York Mary Margaret Basham Nikki Cager Internal Medicine Medicine‐Primary University of Alabama ‐ Birmingham University of Mississippi Medical Center Birmingham, Alabama Jackson, Mississippi Peggy Boles Gunter Cain Anesthesiology Anesthesiology University of Mississippi Medical Center University of Arkansas Jackson, Mississippi Little Rock, Arkansas Philip Carter Taylor Coppage Family Medicine Anesthesiology -

EACHING HOSPITALS ASSOCIATION of AMERICAN MEDICAL COLLEGES 1346 Connecticut Avenue, N.W

q4A- COUNCIL OF TEACHING HOSPITALS ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN MEDICAL COLLEGES 1346 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 202/223-5364 AGENDA EXECUTIVE COMMITNE MEETING #68-3 Thursday and Friday, May 9 and 10, 1968 Hotel Dupont Plaza 1500 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 202/483-6000 Thursday, May 9, 1968: 6:30 p.m. Reception Dupont Room (Lower Level) 7:00 p.m. 1. Dinner Meeting 2. Presentation S. Douglass Cater, Jr.12 Robert Q—Marston, M.D. 10:00 p.m. Recess • Friday, May 10, 1968: 9:30 a.m. Reconvene -7 Conference Room -- 4th Floor, Dupont (to allow for early Circle Building, 1346 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. checkout from Dupont 202/223-5364 Plaza, if desired. A "working lunch" will 3. Approval of Minutes, Executive Committee Tab 1 be served at 12:30 in Meeting #68-2, January 11 & 12, 1968 the Conference Room) 4. Report on Action Items from Executive Tab 2a".41. Committee Meeting of January 11 & 12 '0 • \-.0A exs-C 1.) e. zskeo Q., to Implement "A Guide to C c;.-C 1-1mu_s.eTs-1-00°' • Report on Study Hospitals" (see page 6 of Minutes of Committee Meeting #68-2) Consc-c-o-C,k- tr' Gite to- Executive MC, a---e c-)INcx.A)k • e.p)P1 Status Report on Membership Tab 3/ • c-0 _AR C.9,-ci . 7. New Members Elected by Mail Ballot: A. Scott & White Memorial Hospital* Temple, Texas 1. Special Assistant to the President of the United States 2. Acting Administrator, Health Services and Mental Health Administration, and Director Division of Regional Medical Programs, National Institutes of Health -2- B.