Dilemmas for Natural Living Concepts of Zoo Animal Welfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

Learning About Nature at The

Original citation: Jensen, Eric. (2014) Evaluating children's conservation biology learning at the zoo. Conservation Biology, 28 (4). pp. 1004-1011. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/67222 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Jensen, E. (2014), Evaluating Children's Conservation Biology Learning at the Zoo. Conservation Biology, 28: 1004–1011. doi:10.1111/cobi.12263, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12263. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRAP url’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. -

General Services Big Creek

WILDERNESS TREK Asian ENTRANCE Highlands PARKING Bear Lot Unlock adventure and learn more about your favorite animals. Rosebrough Tiger Passage General Services Big Creek First Aid Lost & Found Restrooms Family Restroom Deckwalk Ben Gogolick Giraffe Encounter Sarah Allison Water Fountains Steffee Center for Zoological Medicine Stroller & Wheelchair Rental Restaurants/Snacks Shopping/Souvenirs ATM Yagga Train Playground Tree Station Daniel Maltz Lorikeet Rhino Reserve Nursing Room Feeding Sensory Inclusive Check-In Complimentary cell phone charging station Reservable Picnic Areas 1 Palava Hut Pavilion 2 Tucker Court Pavilion 3 Wild Wonder Pavilion 4 Nature Nook Pavilion 5 Waterfowl Lake Tent PARKING 6 Primate Picnic Canopy Lion Lot KeyBank ZooKey Locations Purchase Total Experience Pass Pass powered by CPP Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Pass Includes: Welcome Pavilion • KeyBank Zoo Key The Zoo is a smoke-free environment for the safety • Unlimited Boomerang Train, PARKING Zoo Tram Service to: Stork Lot of our animals and the comfort of our guests. Primate, Cat & Aquatics Circle of Wildlife Carousel and Tram routes and times subject to change. 4-D Theater Recycling stations located throughout the Zoo. • Plus $1 off giraffe feeding and lorikeet feeding PARKING Habitats and attractions are subject to change. Tiger & Otter Lots The RainForest Main Entrance Lower Level PUBLIC ANIMAL ACCESS EXHIBITS KAPOK TREE STAIRS REPTILES ELEVATOR LEAF-CUTTER VIDEO BATS ANTS THEATER SPIDERS & AFRICAN INSECTS POND TROPICAL RAINSTORM PORCUPINE AMPHIBIANS TO 2ND GHARIAL LEVEL TURTLES MEDICINE TRAIL SMALL PRIMATES JUNGLE CASCADE TO ORCHID ROOM & JUNGLE LAB MAIN ENTRANCE Together we can Upper Level secure a future for wildlife. KAPOK TREE STAIRS Join our conservation community AGOUTI, PORCUPINE & BINTURONG ELEVATOR Fifty cents from every admission fee RESEARCH helps support Zoo conservation HUT programs to secure a future for wildlife. -

Legal Status of Zoos and Zoo Animals.Pdf

TOWARD A MORE APPROPRIATE JURISPRUDENCE REGARDING THE LEGAL STATUS OF ZOOS AND ZOO ANIMALS By GEORDE DUCKLER* I. INTRODUCTION Zoo animals are currently regarded as objects by the state and federal courts and are perceived as manifesting the legal attributes of amusement parks. The few tort liability cases directly involving zoos tend to view them as markets rather than preserves; the park animals are viewed as dangerous recreational machinery more akin to roller coasters or Ferris wheels than to living creatures.' Courts typically treat zoo keepers and owners as the mechanics and manual laborers responsible for the mainte- nance of these dangerous instrumentalities. 2 Disputes concerning the pos- session, sale and care of exotic animals, as well as'the administration of the habitats in which such animals are housed, have also been treated by the courts in terms of control of materials for public exhibit and entertainment.3 Since zoos do in fact operate primarily as centers of entertainment, it is not surprising that they are characterized as such by the judiciary. Moreover, animals in general have historically been considered the prop- erty of humans, and that courts consider them as such is a topic well ex- plored by authors from many disciplines, including those published in earlier issues of this journal.4 With regard to animals as property, most discussions have focused on one of three specific groups: domesticated animals, animals used in scientific experimentation, or wild animals found on public lands. Zoo animals, on the other hand, occupy a peculiar place in the prop- erty law hierarchy;, a position not as easily or as regularly assessed as * Ph.D. -

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone

Updated February 6th, 2020 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Granby - Quebec Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9101 If the zoo or aquarium to which you Winnipeg - Manitoba Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 belong has 50% in the Reciprocity MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 column, you can expect to receive a Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 50% discount on admission at all the zoos and aquariums on this list Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 (except, of course, those that are Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4393 FREE TO THE PUBLIC ). Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 If the zoo or aquarium to which you Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 belong has 100% and 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can expect California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 to receive free admission to the Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 zoos and aquariums that also have Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office 559-498-5921 100% and 50% in the Reciprocity column and those that are FREE TO Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. -

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact

Updated March 25th, 2021 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Katie Frost 403-232-9386 Granby - Quebe Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept 416-392-9101 Winnipeg - ManiAssiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 If the zoo or aquarium to which MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 expect to receive a 50% discount Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 on admission at all the zoos and Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept 602-914-4393 aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept 877-526-3960 THE PUBLIC). Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept 520-881-4753 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 If the zoo or aquarium to which California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 you belong has 100% and 50% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive free Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office559-498-5921 admission to the zoos and Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept 323-644-4759 aquariums that also have 100% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Membership Dept 510-632-9525 x160 and 50% in the Reciprocity column and those that are FREE Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 TO THE PUBLIC; and a 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Membership Dept 916-808-5888 discount on admission to the San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5310 zoos and aquariums that have 50% in the Reciprocity column. -

North Carolina Zoo Conservation Report

North Carolina Zoo Conservation and Research International 4 Conservation Conservation is at the Heart of Everything We Do. Regional 30 Conservation © Lo ri Wi lliams Conservation © N at rd 38 Education han Shepa © D r . G ra s ham Reynold 44 Research Animal 50 Welfare Our mission is to protect wildlife and wild places and inspire people to join us in conserving the natural world. The North Carolina Zoo’s staff are dedicated to local and global wildlife conservation, educating future generations, and ensuring the best possible care and wellness for the animals under our care. Green Practices We do these things because we believe the diversity of nature is 56 & Sustainability critical for our collective future.” L. Patricia Simmons Director of North Carolina Zoo International Conservation Since 2013, the North Carolina Zoo and the Wildlife Conservation Society have partnered to conduct Tanzania’s first substantial vulture monitoring program. This important collaboration continues to provide guidance to wildlife managers in terms of the overall status of various vulture species, the impact of poisoning events as well as providing protected areas with near real-time poaching-related intelligence to guide their protection operations.” Aaron Nicholas Program Director, Ruaha-Katavi Landscape, Tanzania, Wildlife Conservation Society Tracking Tanzania’s Vultures Vultures are currently the fastest declining Since 2013, the Zoo has worked across group of birds globally, and several African southern Tanzania in two important vulture vulture species are considered Critically strongholds encompassing over 150,000 km2: Endangered. The primary threat to vultures the Ruaha-Katavi landscape and Nyerere is poisoning - often from livestock carcasses National Park. -

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Welcome to the San Diego Zoo Safari Park Please note the Africa Tram is not included with school admission tickets. You must have purchased a separate Africa Tram ticket to experience this attraction. Here are a couple of tips to help you make the most of your day. Chaperones, please share these insider tips with your students. 1. Chaperones, please stay with your students at all times. The Safari Park is a large and exciting place and it is easy to get separated. Lost chaperones are brought to Ranger Base (indicated on reverse) to meet up with your students. 2. For best viewing of our animals, please use low voices, do not bang on the glass and try not to run. The animals will move away or hide from loud noise and fast movements. 3. If you want to feed our animals, please visit Lorikeet Landing (from 10:00 A.M. to 3:45 P.M. Lorikeet food is available for purchase, 10 students at a time), The other animals are on special diets and people food might make them sick. 4. If you want to pet our animals, please visit our Petting Kraal. Your teacher must schedule a visit time if you are visiting October 1st- 31st and May 11th - April 23rd. 5. Have a good time, take lots of pictures and ask questions. Safari Park staff are happy to assist. To further enhance your visit, you may want to see one of our shows or meet one of our animal ambassadors up close by seeing an Animal Encounter. -

The HSUS Investigates: Natural Bridge Zoo in Natural Bridge, Virginia

The HSUS Investigates: Natural Bridge Zoo in Natural Bridge, Virginia During the spring, summer and early fall of 2014, an HSUS investigator went undercover at the Natural Bridge Zoo (NBZ), a tawdry and troubled roadside zoo located in rural Natural Bridge, Virginia, and owned and operated by Karl and Debbie Mogensen. NBZ breeds and sells numerous exotic animals to the pet trade, individuals, other roadside zoos, at auctions and to canned hunt facilities. The Mogensens are affiliated with the Zoological Association of America, a small, deceptively named fringe group that accredits poorly run roadside zoos and supports indiscriminate and unhealthy breeding practices along with the exotic pet trade. Karl Mogensen’s daughter, Gretchen, breeds tiger cubs for use in money- making photo shoots and private play sessions at NBZ. During our investigation, five tiger cubs were born and immediately taken from their mother, Bhuva. Two of the cubs, named Daxx and Deja, were kept by NBZ for a few months while their three siblings were sent to T.I.G.E.R.S., an exotic animal compound in South Carolina that engages in the same cub breeding that has caused an over-population problem and Trip Advisor reviews aptly describe what warehousing of these magnificent animals. disgusted patrons have found during their visits to NBZ: The video and photographic evidence gathered by the HSUS investigator Ü “Size of the area the animals had was demonstrates that Natural Bridge Zoo: very poor. After entering the zoo I left 20 Ü Fails to provide adequate veterinary care to sick and injured minutes later. -

Biodiversity Teacher Resource Booklet

GGRRAADDEE 66 BIODIVERSITY TEACHER RESOURCE BOOKLET TO THE TEACHER Welcome! This resource guide has been designed to help you enrich your students’ learning both in the classroom and at the Toronto Zoo. All activities included in this grade 6 booklet are aligned with the Understanding Life Systems strand of The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 1-8: Science and Technology, 2007. The pre-visit activities have been developed to help students gain a solid foundation about biodiversity before they visit the Zoo. This will allow students to have a better understanding of what they observing during their trip to the Toronto Zoo. The post-visit activities have been designed to help students to reflect on their Zoo experience and to make connections between their experiences and the curriculum. We hope that you will find the activities and information provided in this booklet to be valuable resources, supporting both your classroom teaching and your class’ trip to the Toronto Zoo. CONTENTS Curriculum Connections ................................................................................................ 3 Pre-Visit Activities What is Biodiversity? ............................................................................................. 4 Biodiversity Tray Game ......................................................................................... 5 Junk Box Sorting ................................................................................................... 6 Interactive Animal Sorting ..................................................................................... -

Conservation Biology • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Commonly Asked Questions

Conservation Biology • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Commonly Asked Questions As a conservation Biologist what are the job duties and responsibilities? What are some daily activities? It depends if you are in the field, or in the office. In Denver Zoo’s conservation and research department, the ratio of that is dependent on time of year and project. Often, the organization of data is a huge part of what a conservation biologist does when not in the field. Applying for grants to fund conservation work, planning trips, sometime organizing students and/or volunteers are other responsibilities. If working for a university as a conservation biologist, field research AND working as a professor teaching students is part of a day’s work. When in the field, conservation biologists are typically out looking for sites if one has not been identified or gathering data. What do most people like and dislike about this occupation? Conservation is hard physical work, which includes getting dirty, and being uncomfortable. It can also be dangerous depending on where fieldwork is occurring (animals, political clashes, remote medical issues). If working internationally there can be language barriers and challenges with being far away from home/family. Those same things can be very new and exciting. How a conservation biologist reacts to these challenges often depends on one’s personality and where they are in life. Do you need to go to college to become a Conservation Biologist? Yes! Study topics of the most interest! Look at the courses that make up each major and choose the one that has the courses that are of interest. -

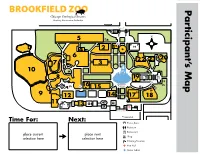

BROOKFIELD ZOO Participant’S Map

BROOKFIELD ZOO Map Participant’s Inspiring Conservation Leadership Enter/Exit Hoofed Animals 5 Camels * 2 1* 4 * 6 22 21 20 7 3 10 8 19 Roosevelt * * 16 Fountain * * 15 * 9 * 12 14 17 18 11 13 * * Enter/Exit Time For: Next: *Seasonal Picnic Area Restroom Restaurant place current place next Shop selection here selection here Drinking Fountain + First Aid Motor Safari Schedule Instructions Visual Schedule Instructions 1. Choose _____ animal photo cards from the Animals section. Number 2. Choose _____ photo cards from the Other Choices section. Number 3. In the Schedule section, post all of the photo cards in the sequence of your choice. (Prepare all cards with a removable adhesive, such as velcro.) Locating and Attending Procedures 1. On the Participant’s Map at the front of this book, post one photo card in the square under Time For, and the next photo card in the square under Next . 2. On the map, find the same number as the photo card. 3. Walk to that area in the zoo. (A responsible adult may use a timer for minimum or maximum attending goals.) 4. When you are finished, post the photo card in the All Done section at the back of this book. 5. Check the Schedule . 6. Repeat steps 1 to 4 until you have posted all photo cards in the All Done section. © 2015 Chicago Zoological Society. The Chicago Zoological Society is a private nonprofit organization that operates Brookfield Zoo on land owned by the Forest Preserves of Cook County. Animals Butterflies! Hoofed Animals Wolf Woods 1* 5 9 Zebra Longwing Bactrian Camel Mexican Gray Wolf Australia