The Role of the HSUS in Zoo Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums

Reciprocity Please Note: Due to COVID-19, organizations on this list may have put their reciprocity program on hold as advance reservations are now required for many parks. We strongly recommend that you call the zoo or aquarium you are visiting in advance of your visit. Thank you for your patience and understanding during these unprecedented times. Wilds Members: Members of The Wilds receive DISCOUNTED or FREE admission to the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. Wilds members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains its own discount policies, and The Wilds strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. Each zoo reserves the right to limit the amount of discounts, and may not offer discounted tickets for your entire family size. *This list is subject to change at any time. Visiting The Wilds from Other Zoos: The Wilds is proud to offer a 50% discount on the Open-Air Safari tour to members of the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. The reciprocal discount does not include parking. If you do not have a valid membership card, please contact your zoo’s membership office for a replacement. This offer cannot be combined with any other offers or discounts, and is subject to change at any time. Park capacity is limited. Due to COVID-19 advance reservations are now required. You may make a reservation by calling (740) 638-5030. You must present your valid membership card along with your photo ID when you check in for your tour. -

Cover Letter

PARC Prisoner Resource Directory - Last Updated April 2014 1 Core Volunteers B♀ (rita d. brown) Greetings, April 2014 Pat Foley Scott Nelson Welcome to the latest edition of the PARC Prisoner Resource Directory, which has been fully updated as of April 2014. We wish to thank those readers who have written back this past year with letters Sissy Pradier and stories and who have returned our evaluation form, as this allows us to get a better idea of the true Penny Schoner readership of the directory and let us know which direction to take when adding new categories or information. Special thanks again to those who pass on the directory – according to your reports, our Taeva Shefler resource directory is widely circulated and viewed by an average of 15 or more people. Mindy Stone Starting with this edition we have reorganized many resources that were formerly listed in individual categories into a state-by-state listing. Thus for instance, the former entries for Innocence Projects, Prison-Based College Programs, and Family & Visiting Resources are now listed in the Community corresponding state in which the organization is based or primarily offers its services. Our other categories Advisory Board with listings affecting prisoners on a nationwide basis will continue with their own sections, such as Women’s Organizations, Death Penalty Resources, and Religious Programs / Spiritual Resources. B♀ (rita d. brown) Rose Braz PARC also has been closely following the ongoing federal lawsuit over cruel and unusual conditions in California’s security housing units (Ashker v Brown, 4:09-cv-05796-CW), which was filed jointly Angela Davis by the nationally-recognized Center for Constitutional Rights, Oakland-based California Prison Focus, and San Francisco-based Legal Services for Prisoners with Children. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

Local Destinations for Children to Interact with Animals Kansas City

veggies being grown. They may even get to sample those What? The Nature Center is home to that are ripe!** many live, native reptiles, amphibians and fish. The Ernie Miller Nature Center surrounding area also features a www.erniemiller.com bird feeding area, garden pool and Where? 909 N. Highway 7 Olathe, Kansas butterfly garden. When? Monday through Saturday 9 AM to 5 PM, Sunday 1 PM to 5 Why? Classes are offered most Saturdays PM (March 1 through October 31) Monday through Saturday (although most are aimed at children 5 and older), and the Local Destinations for Children to Interact with Animals 9 AM to 4:30 PM, Sunday 12:30 PM to 4:30 PM (November 1 park features a stroller-friendly walking trail and takes visitors Kansas City Zoo through February 28); Closed daily for lunch from 12-1 PM; through meadows, past a variety of wildflowers , and along www.kansascityzoo.org closed on Sundays June, July and August. the creek where children can easily spot native animals. Where? 6800 Zoo Drive (inside Kansas City, Missouri’s Swope Park) What? The Center provides an opportunity for learning, When? Open year round 9:30 AM to 4PM (Closed Thanksgiving Day, understanding, and admiring nature’s ever-changing ways. Anita B. Gorman Discovery Center Christmas Day and New Year’s Day) The Center contains displays and live animals, along with a http://mdc.mo.gov/regions/kansas-city/discovery-center What? Recognized as one of “America’s Best Zoos, “the Kansas City friendly, knowledgeable staff eager to share their knowledge Where? 4750 Troost Avenue, Kansas City, Missouri Zoo is a 202-acre nature sanctuary providing families with of nature. -

2006 Reciprocal List

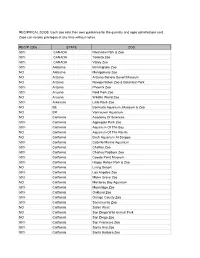

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Kczoo Reopening to the Public with Precautions

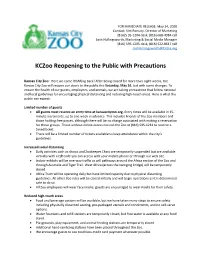

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 14, 2020 Contact: Kim Romary, Director of Marketing (816)5 95-1204 desk, (816) 668-4984 cell Josh Hollingsworth, Marketing & Social Media Manager (816) 595-1205 desk, (816) 522-8617 cell [email protected] KCZoo Reopening to the Public with Precautions Kansas City Zoo: Here we come ROARing back! After being closed for more than eight weeks, the Kansas City Zoo will reopen our doors to the public this Saturday, May 16, but with some changes. To ensure the health of our guests, employees, and animals, we are taking precautions that follow national and local guidelines for encouraging physical distancing and reducing high-touch areas. Here is what the public can expect: Limited number of guests • All guests must reserve an entry time at kansascityzoo.org. Entry times will be available in 15- minute increments, up to one week in advance. This includes Friends of the Zoo members and those holding free passes, although there will be no charge associated with making a reservation for these groups. Those without online access can call the Zoo at (816) 595-1234 to reserve a timed ticket. • There will be a limited number of tickets available to keep attendance within the city’s guidelines. Increased social distancing • Daily activities such as shows and Zookeeper Chats are temporarily suspended but are available virtually with a QR code you can access with your mobile phone or through our web site. • Indoor exhibits will be one-way traffic as will pathways around the Africa section of the Zoo and through Australia and Tiger Trail. -

ASIAN ELEPHANT WC 36 (Elephas Maximus) NORTH AMERICAN REGIONAL STUDBOOK UPDATE

ASIAN ELEPHANT WC 36 (Elephas maximus) NORTH AMERICAN REGIONAL STUDBOOK UPDATE 1 MAY 2005 - 16 JULY 2007 MIKE KEELE - STUDBOOK KEEPER KAREN LEWIS - CONSERVATION PROGRAM ASSISTANT TERRAH OWENS - CONSERVATION INTERN PL 16303 PL 16304 NORTH AMERICAN REGIONAL STUDBOOK – ASIAN ELEPHANT i MESSAGE FROM THE STUDBOOK KEEPER This studbook update does not contain historical information. The last complete studbook was current through 30 April 2005 and was published and distributed in 2005/06. This Update includes information on Asian elephants that were living or died during the reporting period (1 May 2005 through 16 July 2007), 287 living elephants are included here – 50 males and 220 females. Much of the work associated with publishing this Studbook Update was performed by Karen Lewis. Karen serves the Oregon Zoo as our Conservation Program Assistant. She surveyed facilities, validated data, and made contact with many of you who have contributed animal information to the Studbook. Conservation interns Stephanie Dobson & Terrah Owens were instrumental in getting this Studbook Update ready for publication. Terrah formatted all of the studbook reports and created the pdf document. We will continue our effort to validate historical information and we expect to be contacting many of you to assist us with that effort. Special thanks for all of you who have been responsive to our requests for information and for responding to our surveys. We could not have accomplished this publication without your efforts. Additional information or corrections are enthusiastically welcomed and should be forwarded to either myself or Karen. Mike Keele – Deputy Director Karen Lewis – Cons. Prog. Asst. Oregon Zoo Oregon Zoo 4001 S.W. -

RECIPROCAL LIST from YOUR ORGANIZATION and CALL N (309) 681-3500 US at (309) 681-3500 to CONFIRM

RECIPROCAL LOCAL HIGHLIGHTS RULES & POLICIES Enjoy a day or weekend trip Here are some important rules and to these local reciprocal zoos: policies regarding reciprocal visits: • FREE means free general admission and 50% off means 50% off general Less than 2 Hours Away: admission rates. Reciprocity applies to A Peoria Park District Facility the main facility during normal operating Miller Park Zoo, Bloomington, IL: days and hours. May exclude special Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. exhibits or events requiring extra fees. RECIPROCAL Henson Robinson Zoo, Springfield, IL: • A membership card & photo ID are Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. always required for each cardholder. LIST Scovill Zoo, Decatur, IL: • If you forgot your membership card Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. at home, please call the Membership Office at (309) 681-3500. Please do this a few days in advance of your visit. More than 2 Hours Away: • The number of visitors admitted as part of a Membership may vary depending St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO: on the policies and level benefits of Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general the zoo or aquarium visited. (Example, admission and 50% off Adventure Passes. some institutions may limit number of children, or do not allow “Plus” guests.) Milwaukee Zoo, Milwaukee, WI: Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. • This list may change at anytime. Please call each individual zoo or aquarium Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL: BEFORE you visit to confirm details and restrictions! Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general admission and 10% off retail and concessions. DUE TO COVID-19, SOME FACILITIES Cosley Zoo, Wheaton, IL: MAY NOT BE PARTICIPATING. -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ...