How and Why We Blame the Victims of Street Harassment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harassment and Victimisation Introduction

Harassment and victimisation Introduction Stockholm University is to be characterised by its excellent environment for work and study. All employees and students shall be treated equally and with respect. At Stockholm University we shall jointly safeguard our work and study environment. A good environment enables creative development and excellent outcomes for work and study. At Stockholm University, victimisation, harassment associated with discrimination on any grounds and sexual harassment are unacceptable and must not take place. Victimisation, harassment and sexual harassment all jeopardise the affected person's job satisfaction and chances of success in work or study. As soon as the university becomes aware that someone has been affected, action will be taken immediately. In this brochure, Stockholm University explains • the forms that victimisation, harassment and sexual harassment may take, • what you can do if you or someone else becomes subjected to such behaviour, • the university's responsibilities, • the sanctions faced by those subjecting a person to victimisation, harassment or sexual harassment. Astrid Söderbergh Widding Vice-Chancellor Production: Human Resources Office, Student Services, Council for Equal Opportunities and Equality, and Matador kommunikation. Illustrations: Jan Ed. Printing: Ark-Tryckaren, 2015. 3 What is victimisation? All organisations experience occasional differences of opinion, conflicts and difficulties in working together. However, these occasional conflicts are not considered victimisation or bullying. Victimisation is defined as recurrent reprehensible or negative actions directed against individuals and that may lead to the person experiencing it being marginalised. Examples include deliberate insults, demeaning treatment, ostracism, withholding of information, persecution or threats. Victimisation brings with it the risk that individuals as well as entire groups will be adversely affected, in both the short and long terms. -

The Bullying of Teachers Is Slowly Entering the National Spotlight. How Will Your School Respond?

UNDER ATTACK The bullying of teachers is slowly entering the national spotlight. How will your school respond? BY ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK ON NOVEMBER !, "#!$, Teaching Tolerance (TT) posted a blog by an anonymous contributor titled “Teachers Can Be Bullied Too.” The author describes being screamed at by her department head in front of colleagues and kids and having her employment repeatedly threatened. She also tells of the depres- sion and anxiety that plagued her fol- lowing each incident. To be honest, we debated posting it. “Was this really a TT issue?” we asked ourselves. Would our readers care about the misfortune of one teacher? How common was this experience anyway? The answer became apparent the next day when the comments section exploded. A popular TT blog might elicit a dozen or so total comments; readers of this blog left dozens upon dozens of long, personal comments every day—and they contin- ued to do so. “It happened to me,” “It’s !"!TEACHING TOLERANCE ILLUSTRATION BY BYRON EGGENSCHWILER happening to me,” “It’s happening in my for the Prevention of Teacher Abuse repeatedly videotaping the target’s class department. I don’t know how to stop it.” (NAPTA). Based on over a decade of without explanation and suspending the This outpouring was a surprise, but it work supporting bullied teachers, she target for insubordination if she attempts shouldn’t have been. A quick Web search asserts that the motives behind teacher to report the situation. revealed that educators report being abuse fall into two camps. Another strong theme among work- bullied at higher rates than profession- “[Some people] are doing it because place bullying experts is the acute need als in almost any other field. -

Rehabilitating a Federal Supervisor's Reputation Through a Claim

Title VII and EEOC case law have created an almost blanket protection for defamatory statements made in the form of allegations of harassment or discrimination in the federal workplace. In this environment, federal supervisors would do well to exercise caution before resorting to the intui- tive remedy of a defamation claim. Although there are some situations where an employee may engage in action so egregious that a claim of defamation is a good option, one cannot escape the fact that supervisory employment in the federal workplace comes with an increased risk of defamatory accusations for which there is no legal remedy. BY DANIEL WATSON 66 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2014 Rehabilitating a Federal Supervisor’s Reputation Through a Claim of Defamation ohn Doe is a supervisor for a federal and demeaning insults he was alleged to have yelled at Jane agency. As he was leaving the office one Doe, and sex discrimination for his refusal to publish her work. Outraged at the false accusation, John immediately called Jnight, a female subordinate, Jane Doe, Jane into his office and asked her how she could have lied. Did stopped and asked why her work product she not know it was illegal to lie about that type of behavior? Jane responded by accusing John of retaliation. A week after had not received approval for publication. the incident, while speaking to a coworker, John Doe discov- He attempted to explain that he had already ered that the coworker had overheard the entire conversation documented his critique via e-mail and that between John and Jane and would swear to the fact that Jane was lying about what was said. -

Defamation in the Era of #Metoo

Defamation in the Era of #MeToo: An Introduction to Defamation Claims Related to Sexual Harassment Why are we here? Just to name a few… What Does Sexual Harassment Have To Do With Defamation? • There is an increasing trend in the filing of defamation lawsuits pertaining to allegations of sexual misconduct. - Ratner v. Kohler (D. Haw.) - Elliott v. Donegan (E.D.N.Y) - Unsworth v. Musk (C.D. Cal.) - McKee v. Cosby (1st Circuit) - Zervos v. Trump (N.Y. Sup. Ct.) - Stormy Daniels v. Trump (C.D. Cal.) • The changing political climate toward the freedom of the press has also given rise to recent defamation lawsuits. • Palin v. New York Times (S.D.N.Y) What is Defamation? A publication of or concerning a third party that … . Contains a false statement of fact, . Carries a defamatory meaning, and . Is made with some level of fault. Types of Defamation Libel v. Slander “Libel and slander are both methods of defamation; the former being expressed by print, writing, pictures or signs; the latter by oral expressions or transitory gestures.” Libel Per Se • The four established “per se” categories are statements • Charging a plaintiff with a serious crime; • That tend to injure another in his or her trade, business or profession; • That a plaintiff has a loathsome disease; or • Imputing unchastity to a woman What is a “Publication”? Classic publications: . Books . News articles . Opinion columns . Advertisements & billboards . Oral communications What is a “Publication”? But how about … . Blogs? . Tweets? . Facebook posts? . Instagram pictures? . Online comments? What is “Of” or “Concerning”? • The statement is “of and concerning” the plaintiff when it “designates the plaintiff in such a way as to let those who knew [the plaintiff] understand that [he] was the person meant. -

Bullying and Harassment of Doctors in the Workplace Report

Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace Report May 2006 improving health Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Contents List of tables and figures . 2 Executive summary . 3 Introduction. 5 Defining workplace bullying and harassment . 6 Types of bullying and harassment . 7 Incidence of workplace bullying and harassment . 9 Who are the bullies? . 12 Reporting bullying behaviour . 14 Impacts of workplace bullying and harassment . 16 Identifying good practice. 18 Areas for further attention . 20 Suggested ways forward. 21 Useful contacts . 22 References. 24 Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace 1 Health Policy & Economic Research Unit List of tables and figures Table 1 Reported experience of bullying, harassment or abuse by NHS medical and dental staff in the previous 12 months, 2005 Table 2 Respondents who have been a victim of bullying/intimidation or discrimination while at medical school or on placement Table 3 Course of action taken by SAS doctors in response to bullying behaviour experienced at work (n=168) Figure 1 Source of bullying behaviour according to SAS doctors, 2005 Figure 2 Whether NHS trust takes effective action if staff are bullied and harassed according to medical and dental staff, 2005 2 Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Executive summary • Bullying and harassment in the workplace is not a new problem and has been recognised in all sectors of the workforce. It has been estimated that workplace bullying affects up to 50 per cent of the UK workforce at some time in their working lives and costs employers 80 million lost working days and up to £2 billion in lost revenue each year. -

Workplace Bullying and Harassment

AMA Position Statement Workplace Bullying and Harassment 2009 Introduction There is good evidence that bullying and harassment of doctors occurs in the workplace. One Australian study found that 50% of Australian junior doctors had been bullied in their workplace, and a New Zealand study reported that 50% of doctors had experienced at least one episode of bullying behaviour during their previous three or sixth-month clinical attachment. 1 2 Workplace bullying of members of the medical workforce can occur between colleagues students and employees, and any contractors, patients, and family members with whom they are dealing. The aims of this position statement are to: • provide a guide for all doctors, hospital and practice managers to identify and manage workplace bullying and harassment, • raise awareness and reduce the exposure of doctors to workplace bullying and harassment, and • assist the medical profession in combating its perpetuation. Definition Workplace bullying is defined as a pattern of unreasonable and inappropriate behaviour towards others, although it may occur as a single event. Such behaviour intimidates, offends, degrades, insults or humiliates an employee. It can include psychological, social, and physical bullying.3 Most people use the terms ‘bullying’ and ‘harassment’ interchangeably and bullying is often described as a form of harassment. The range of behaviours that constitutes bullying and harassment is wide and may include: • physical violence and intimidation, • vexatious reports and malicious rumours, • verbal threats, yelling, screaming, offensive language or inappropriate comments, • excluding or isolating employees (including assigning meaningless tasks unrelated to the job or giving employees impossible tasks or enforced overwork), • deliberately changing work rosters to inconvenience particular employees, • undermining work performance by deliberately withholding information vital for effective work performance, and • inappropriate or unwelcome sexual attention. -

BOT Report 09-Nov-20.Docx

REPORT 9 OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES (November 2020) Bullying in the Practice of Medicine (Reference Committee D) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY At the 2019 Annual Meeting Resolution 402-A-19, “Bullying in the Practice of Medicine,” was introduced by the Young Physicians Section and referred by the House of Delegates (HOD) for report back at the 2020 Annual Meeting. The resolution asks the American Medical Association (AMA) to help (1) establish a clear definition of professional bullying, (2) establish prevalence and impact of professional bullying, and (3) establish guidelines for prevention of professional bullying. This report provides statistics and other information about the prevalence and impact of professional bullying in the practice of medicine, and makes recommendations for the adoption of a formal definition and guidelines for establishing policies and strategies for preventing and addressing incidents of bullying among the health care staff. Bullying in the practice of medicine for physicians can begin in medical school and can endure throughout a physician’s career. Bullying is not limited to physicians and can happen among other members of the health care team. Bullying has many definitions, all commonly referring to the repeated abuse of a target by a perpetrator in a work setting. Bullying occurs at different levels within the practice of medicine, and affects the victim as well as their patients, care teams, organizations, and families. Nationally recognized organizations have established guidelines on which health care employers can base their internal policies, and many organizations have implemented anti-bullying or anti-violence policies. Bullying in medicine needs to be stopped and prevented for the sake of patients and care quality, the well- being of the physician workforce, and the integrity of the medical profession. -

APS Bullying and Harassment Brochure REVISED Oct 2015-2016

What Is Bullying/Harassment Bullying/Harassment? Can Include: Arlington Public Schools defines bullying/harassment, includ- • Name calling ing bullying/harassment based on an actual or perceived characteristic such as race, national origin, creed, color, • Teasing, making fun of someone religion, ancestry, gender, age, sexual orientation, gender • Spreading rumors and gossip identity and expression, or disability, as the repeated inflic- tion or attempted infliction of injury, discomfort, or humiliation • Insulting someone on a student by one or more students. It is a pattern of ag- gressive, intentional or hostile behavior that occurs repeatedly • Telling or writing lies about someone and over time. Bullying/harassment typically involves an im- balance of power or strength. Bullying/harassment behaviors • Expressing sarcasm, subtle negative comments may include physical, verbal, or nonverbal behaviors. These • Excluding specific persons behaviors include, but are not limited to; intimidation, assault, - extortion, oral or written threats, teasing, name calling, threat- • Pushing, tripping, hitting ening looks, gestures or actions, rumor spreading, false accu- - sations, hazing, social isolation, and abusive e mails, phone • Ridiculing Bullying calls, or other forms of cyber bullying. The term “cyberbullying” is used when text, photos, videos or other • Threatening, intimidating or scaring people media are uploaded to computers and/or internet to de- • Belittling people because of their race or culture fame, insult, harass or haze others. and • Making sexual comments or innuendos Every child deserves a safe and respectful environment. Parents and school staff must work together to provide this Harassment environment. Parents can be instrumental in helping their child by learning the signs of bullying/harassment and by knowing strategies to deal with it if it occurs. -

IM-2013-06 -2- Because Bullying Is Generally Concentrated Among School Children, Policies Are Included in Ch

WISCONSIN LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM Cyber-Bullying and General Bullying Laws in Wisconsin Increasing adolescent access to the Internet and wireless phones have caused a general increase in a practice that was previously reserved for face-to-face confrontation-bullying. When the practice of bullying incorporates the use of websites, email, and text messages, it is often referred to as cyber-bullying. Cyber-bullying may be generally defined as using electronic devices such as computers, mobile telephones or tablets to engage in behavior which is intended to cause fear, intimidation or harm to others. The National Crime Prevention Association (NCPA) gives the following examples of cyber-bullying: Sending someone mean or threatening emails, instant messages, or text messages. Excluding someone from an instant messenger buddy list or blocking their email for no reason. Tricking someone into revealing personal or embarrassing information and sending it to others. Breaking into someone’s email or instant message account to send cruel or untrue messages while posing as that person. Creating websites to make fun of another person such as a classmate or teacher. Using websites to rate peers as prettiest, ugliest, etc. In Wisconsin, there are a number of laws that are intended to prevent the practice of bullying in general, as well as the specific practice of cyber-bullying. Cyber-bullying, or the practice of using electronic devices such as computers, mobile telephones or tablets to engage in behavior which is intended to cause fear, intimidation, or harm to others, is generally prohibited in Wisconsin. However, there is not a single statutory section specifically prohibiting cyber-bullying. -

Harassment, Victimisation and Bullying Policy

HARASSMENT, VICTIMISATION AND BULLYING POLICY PREAMBLE This Policy aims to promote a safe, flexible and respectful environment in the College. An environment that values diversity for staff and students and is free of Harassment, Victimisation and Bullying. All students and staff are required to treat each other with dignity, courtesy and respect which helps create an environment within the College where the most beneficial learning, teaching and administration duties can be carried out. DEFINITIONS “Bullying” occurs when a person or a group of people repeatedly behave unreasonably towards a worker or a group of workers and the behaviour creates a risk to health and safety. Bullying does not include reasonable management action carried out in a reasonable manner. “College” means Australian Pacific College, English Unlimited and Australian Pacific Travel and Tourism. “Harassment” means any type of behaviour that a person does not want and does not return and may offend embarrass, or scare them, and is either sexual or targets them because of their race, sex, pregnancy, marital status, carer’s responsibilities, transgender, homosexuality, disability or age. “National Code” means the National Code of Practice for Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 2018. “Order” means an order made by the Fair Work Commission under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). “Policy” means this Harassment, Victimisation and Bullying Policy. “Student” means any person undertaking a course of study at the College,. “Victimisation” is any situation where a person is threatened because they are making or proposing to make a complaint under equal opportunity laws. “Worker” means an employee, a contractor or subcontractor or a person employed by a labour hire company who is working at a particular business or organisation, an outworker, an apprentice or a trainee, a work experience student, a volunteer. -

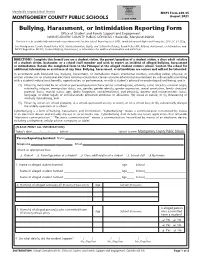

MCPS Bullying, Harassment, Or Intimidation Report Form

MCPS Form 230-35 August 2021 Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation Reporting Form Office of Student and Family Support and Engagement MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS • Rockville, Maryland 20850 This form is to be confidentially maintained in accordance with the Safe Schools Reporting Act of 2005, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1232g. See Montgomery County Board Policy ACA, Nondiscrimination, Equity, and Cultural Proficiency, Board Policy JHF, Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation, and MCPS Regulation JHF-RA, Student Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation for additional information and definitions. DIRECTIONS: Complete this form if you are a student victim, the parent/guardian of a student victim, a close adult relative of a student victim, bystander, or a school staff member and wish to report an incident of alleged bullying, harassment or intimidation. Return the completed form to the Principal at the alleged student victim’s school. Contact the school for additional information or assistance at any time. Bullying, harassment, or intimidation are serious and will not be tolerated. In accordance with Maryland law, bullying, harassment, or intimidation means intentional conduct, including verbal, physical, or written conduct or an intentional electronic communication that creates a hostile educational environment by substantially interfering with a student’s educational benefits, opportunities, or performance, or with a student’s physical or psychological well-being, and is: (1) Either (a) motivated by an actual -

5. Internet – Addressing the Challenge

5. Internet – Addressing the challenge “To deny people their human rights is to challenge their very humanity.” Nelson Mandela, Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 1993, anti-apartheid activist, President of South Africa 1994-1999 “The rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.” John F. Kennedy, President of the USA 1961-1963 CHECKLIST FACT SHEET 19 – CYBERCRIME: SPAM, MALWARE, FRAUD AND SECURITY Have you set up strong different passwords for your accounts and configured two-factor security? Have you explored security settings for your devices/accounts? Are your operating system and your applications up to date? Have you made a backup of your most important data? CHECKLIST FACT SHEET 20 – LABELLING AND FILTERING Have you thought about the cultural and moral implications of filtering? Do you know the difference between a “black list” and a “white list”? Are you familiar with the most commonly used labelling systems for children’s content, and what they signify? CHECKLIST FACT SHEET 21 – ONLINE HARASSMENT: BULLYING, STALKING AND TROLLING Do you have a clear family or school policy in place so that children understand the repercussions when they are involved in online harassment? Do you protect your personal details sufficiently? Many online problems are caused through ill- advised sharing of photos and information. Have you investigated how to build better social and emotional skills (otherwise known as social literacy) to overcome the anonymity and “facelessness” of online communication that facilitate bullying,