Regular Medicine: Can’T Live Without, Won’T Heal Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Report

Celebrating 175 years The Faculty of Homeopathy Newsletter November 2019 Public pressure forces the publication of the ‘hidden’ Australian report ampaigners have succeeded Interestingly, she went on to issue a in forcing Australia’s leading clarification in relation to the second Cresearch organisation to publish review, stating that it “did not conclude a report on homeopathy that it had that homeopathy was ineffective”. This tried to suppress. Its publication has been raises the question as to why the NHMRC hailed as “a major win for transparency did not try to correct the damning and public accountability in research”. reports to the contrary that appeared The 300-page draft report was in the media and repeated by anti- the result of a study conducted in homeopathy campaigners. 2012 into the clinical effectiveness of Rachel Roberts, HRI chief homeopathy by Australia’s National executive, said: “For over three years Health and Medical Research Council the NHMRC have refused to release (NHMRC), but the research body their 2012 draft report on homeopathy, decided not to make its findings Rachel Roberts, HRI chief executive despite Freedom of Information public. Instead, it commissioned requests and even requests by members a second review that concluded campaign calling on the NHMRC to of the Australian Senate. To see this homeopathy had no therapeutic value publish the first report, which resulted document finally seeing the light of beyond placebo. On publication in in tens of thousands of people signing day is a major win for transparency 2015, the review’s findings were widely an online petition and questions being and public accountability in research.” reported in the media as the definitive asked in the Australian Senate. -

GO FIGURE: MAKING the ECONOMIC CASE for HOMEOPATHY Report Prepared for the Faculty of Homeopathy

GO FIGURE: MAKING THE ECONOMIC CASE FOR HOMEOPATHY Report prepared for the Faculty of Homeopathy Final Report November 2016 Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Homeopathy in perspective ................................................................................................................... 3 What is Homeopathy? .................................................................................................................... 3 Regulation of Homeopathy ............................................................................................................. 4 Current position on funding in the NHS .......................................................................................... 4 Homeopathy and the House of Commons Science and Technology Inquiry ....................................... 5 Summary of the case made to the Committee for and against Homeopathy ................................ 6 Factors underlying the Committee’s conclusions ........................................................................... 7 Evidence of economic benefits and the role of NICE ...................................................................... 8 The Government Response to the Committee .............................................................................. -

A Day in the Life

NEWS FEATURE A day in the life Landmark conference ‘New Horizons in Water Science: Evidence for Homeopathy?’ (with apologies to J Lennon & P McCartney) by Lionel Milgrom PhD MARH RHom and Dana Ullman MPH CCH Foreword Some people not only have good ideas, but are also prepared to work hard to bring those ideas into fruition. Ken (or Lord Aaron Kenneth Ward Atherton, to give him his proper title) is one such person. He decided that we all needed a strong antidote to the ‘no evidence’ claims so frequently vaunted by the anti-homeopathy campaigners, and he organised a truly unforgettable one-day event (held at the Royal Society of Medicine, London), to remind us that Lionel (LRM) has been a homeopath for ‘proper’ science can be fascinating, inspiring and truly uplifting. over 20 years, training at the now defunct Ken’s impressive line-up of presenters were all internationally re- London College of Homeopathy, and the nowned scientists, including two Nobel laureates, and the theme Orion course in advanced homeopathy. He of the event was to explore the science underpinning our knowledge works from home now but has laboured of water structures. I came away from the day feeling really positive; at Nelsons, Ainsworths, and an integrated our emerging understanding of the science of water structures may dental practice in London’s West End. He is well lead us to eventually being able to explain how homeopathy also a scientist (chemist; co-founding an can work at a purely energetic level. On behalf of Team ARH and anticancer biotech spinout company), the rest of the homeopathy community, I would like to thank Ken a science writer, and in his latest incarna- for having the determination, perseverance and, above all, the vision tion, a chemistry teacher. -

Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 HC 45 House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy Fourth Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 8 February 2010 HC 45 Published on 22 February 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Science and Technology Committee The Science and Technology Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Government Office for Science. Under arrangements agreed by the House on 25 June 2009 the Science and Technology Committee was established on 1 October 2009 with the same membership and Chairman as the former Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee and its proceedings were deemed to have been in respect of the Science and Technology Committee. Current membership Mr Phil Willis (Liberal Democrat, Harrogate and Knaresborough)(Chairman) Dr Roberta Blackman-Woods (Labour, City of Durham) Mr Tim Boswell (Conservative, Daventry) Mr Ian Cawsey (Labour, Brigg & Goole) Mrs Nadine Dorries (Conservative, Mid Bedfordshire) Dr Evan Harris (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Abingdon) Dr Brian Iddon (Labour, Bolton South East) Mr Gordon Marsden (Labour, Blackpool South) Dr Doug Naysmith (Labour, Bristol North West) Dr Bob Spink (Independent, Castle Point) Ian Stewart (Labour, Eccles) Graham Stringer (Labour, Manchester, Blackley) Dr Desmond Turner (Labour, Brighton Kemptown) Mr Rob Wilson (Conservative, Reading East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152. -

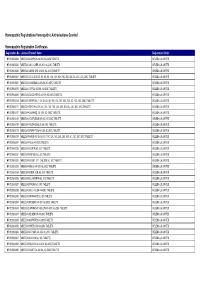

HR & NR Listing with Product Name (FINAL) 18-05-2021

Homeopathic Registrations/Homeopathic Authorisations Granted Homeopathic Registration Certificates Registration No. Licensed Product Name Registration Holder HR 00298/0006 WELEDA ACID PHOS 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0020 WELEDA CALC. CARB. 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0033 WELEDA CARBO VEG 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0047 WELEDA COCCULUS 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0061 WELEDA CHAMOMILLA 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0075 WELEDA COFFEA 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0089 WELEDA COLOCYNTHIS 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0103 WELEDA HEPAR SULF. 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0117 WELEDA IGNATIA 4X, 5X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0131 WELEDA KALI PHOS. 4X- 30X, 6C- 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0145 WELEDA LYCOPODIUM 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0159 WELEDA PHOSPHOROUS 4X-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0173 WELEDA SYMPHYTUM 4X-30X, 6C-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0187 WELEDA TAMUS 4X, 5X, 6X, 8X, 10X, 12X, 15X, 20X, 25X, 30X, 6C, 12C, 30C, 200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0201 WELEDA THUJA 4X-200C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0228 WELEDA ACONITE 6C, 30C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0231 WELEDA APIS MEL 6C, 30C TABLETS WELEDA UK LIMITED HR 00298/0232 WELEDA ARGENT. -

As Homeopathy Progresses Through the Third Century Since Its Founding by Samuel Hahnemann, It Is Timely to Reflect – Not

FEATURE Of milestones and millstones by Jerome Whitney As homeopathy progresses through the third century since its founding by Samuel Hahnemann, it is timely to reflect – not Jerome became involved in homeopathy only on milestones that have been achieved as a student of Dr Thomas Maughan. He but also millstones that have hindered or remains continuously active in the promo- tion and education of homeopathy. His delayed progress. teaching and writings focus on the healing principles from which it has evolved, their When embarking on a journey it the increasingly conservative Hah- expression in the present, and ways to is essential to be clear about one’s bring scientific and practice advances into nemann. Organon 5-6 represent an being for the future. As well as being an current position so that there is increasingly flexible approach to ongoing participant in meditative provings, a solid platform from which to prescribing. Jerome is also currently creating and measure progress. In this article, The fourth edition may be viewed leading a home schooling course titled the focus is on five major homeo- as the point when Hahnemann ‘Explorations in conceptual thinking’. pathic innovators whose significant His enjoyment for hiking and biking introduced his most conservative continues when the sun shines. contributions we now take for rules concerning the practice of ho- granted. It also explores circum- meopathy (4th edition, para 242): stances that have shaped homeo- a) The dosage is to be the single pathy from 1810 to the present administration of a few poppy- and which serve as the foundation seed size pills. -

Simile Jan 10

smle The Faculty of Homeopathy Newsletter April 2010 Flawed report misrepresents homeopathy The Faculty of Homeopathy, along with the British Homeopathic Association has responded in detail to the recommendations in the recently published House of Commons Science and Technology Report which calls for the withdrawal of NHS funding for homeopathy. The two organisations are currently t d i formalising a complaint to Parliament m h c S and have approached key MPs s i r including Secretary of State for Health h C / m Andy Burnham (pictured). They will o c . o argue that the Department of Health t o h which is responding on behalf of p k c o government should note that the t s i : Report was flawed and that there is o t o h research evidence that demonstrates P homeopathy to be effective. The BHA and the Faculty will point opposite by restricting the investigation in the report, one of whom dissented out that it is unfair and undemocratic to the narrow remit of Randomised on the recommendations was Ian for the Science and Technology Controlled Trials. Stewart. In addition, of the three that Committee to put forward Cristal Sumner, chief executive of voted in favour one is long term recommendations that misrepresented Faculty of Homeopathy, said: “The detractor Evan Harris and another MP scientific evidence to the detriment committee did not entertain evidence was brought on to the committee in of homeopathy especially as Phil Wills, of effectiveness, which is actually what January after the hearings. chair of the committee, went on record patients care most about. -

Clare Metcalf Animal Communicator, Healer, Homeopath Rshom, MNCHM, Dip Hom Med, Dip Vet Hom

Clare Metcalf Animal Communicator, Healer, Homeopath RSHom, MNCHM, Dip Hom Med, Dip Vet Hom Homeopathic Remedies for use in First Aid Situations Homeopathy works on 2 major principles, the first being Like Cures Like, that is, a substance which can cause symptoms in a healthy person (such as arsenic) could also be used to treat people suffering from similar symptoms to those produced by the poison. The second principle is that of the Minimum Dose – the physician should choose the appropriate medicine and prescribe it in the minimum dosage possible to induce cure and not exacerbate symptoms, or create new ones (For example modern anti- inflammatory medicines can cause issues with the stomach lining, leading to acid indigestion, stomach ulcers, nausea etc, which may require an additional prescription to treat.) In fact Hahnemann realised that the more dilute the dose, the stronger the curative effects. And this is where many conventional medics believe Homeopathy cannot be effective. But they are working with half the facts. Dilution alone does not create homeopathic remedies. Dilution, along with succession – or vigorous shaking, is what increases the strength of the remedy. Homeopathy is an energetic, vibrational medicine, it is not merely diluted poisons. So it takes a skilled prescriber to know the appropriate remedy (out of over 4000 available) to treat the patient, and also to know the appropriate dosage and repetition of the dose for optimum effect. Homeopathy treats the person not the symptoms. So while it is useful to have a list of ailments the patient suffers with, we must also understand the patient’s personality and how they deal with those particular symptoms, what may have caused the current symptoms as well as previous medical history and additional current complaints. -

Simile April 09.Qxd

smleThe Faculty of Homeopathy Newsletter April 2009 TWHH closes but demand for homeopathy still strong After a prolonged and passionately- fought battle to save the service, the Tunbridge Wells Homeopathic Hospital closed its doors to homeopathy patients for the final time at the end of March. It brings to an end 106 continuous years of homeopathy on the National Health Service there. The hospital began life as a dispensary back in 1863 in The Pantiles, the elegant pedestrianised area of Tunbridge Wells. The dispensary moved to Hanover Road in 1886, and then to Grosvenor Road in 1887, where two houses were converted into a small hospital. The final move came in 1903, to premises on Church Road. Further wings were added to the building in the 1920s and 30s and the hospital supported a small in-patient service until the 1980s. At this time the outpatient service Faculty Chief Executive Cristal Sumner accepts a portrait of Hahnemann from started to expand. Anne Clover, who Tunbridge Wells consultants David Ratsey and Helmut Roniger, signifying the end of was a consultant at TWHH 1980-2001, an era at the hospital. Over 70 people gathered at TWHH on 14 March to mark the remembers: “Demand grew for closure of the service: as well as local patients and former staff, the Mayor and Mayoress of Tunbridge Wells and Greg Clark MP were in attendance; conversations homeopathy throughout the 1980s and were positive about the future provision of a homeopathic service in the town and early 1990s. In 1980 we started with the issue was once again highlighted in the local press. -

Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trials of Individualised Homeopathic

Mathie et al. Systematic Reviews 2014, 3:142 http://www.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/3/1/142 RESEARCH Open Access Randomised placebo-controlled trials of individualised homeopathic treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis Robert T Mathie1*, Suzanne M Lloyd2, Lynn A Legg3, Jürgen Clausen4, Sian Moss5, Jonathan RT Davidson6 and Ian Ford2 Abstract Background: A rigorous and focused systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of individualised homeopathic treatment has not previously been undertaken. We tested the hypothesis that the outcome of an individualised homeopathic treatment approach using homeopathic medicines is distinguishable from that of placebos. Methods: The review’s methods, including literature search strategy, data extraction, assessment of risk of bias and statistical analysis, were strictly protocol-based. Judgment in seven assessment domains enabled a trial’s risk of bias to be designated as low, unclear or high. A trial was judged to comprise ‘reliable evidence’ if its risk of bias was low or was unclear in one specified domain. ‘Effect size’ was reported as odds ratio (OR), with arithmetic transformation for continuous data carried out as required; OR > 1 signified an effect favouring homeopathy. Results: Thirty-two eligible RCTs studied 24 different medical conditions in total. Twelve trials were classed ‘uncertain risk of bias’, three of which displayed relatively minor uncertainty and were designated reliable evidence; 20 trials were classed ‘high risk of bias’. Twenty-two trials had extractable data and were subjected to meta-analysis; OR = 1.53 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.91). For the three trials with reliable evidence, sensitivity analysis revealed OR = 1.98 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.38). -

PDF Download the Bach Flower Remedies

THE BACH FLOWER REMEDIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Bach,F. J. Wheeler | 192 pages | 01 Nov 1998 | Keats Pub Inc | 9780879838690 | English | New Canaan, CT, United States The Bach Flower Remedies PDF Book They often take alcohol or drugs in excess, to stimulate them and help themselves bear their trials with cheerfulness. Conclusion Our review demonstrates that the currently available evidence indicates that BFRs are not more efficacious than a placebo intervention for psychological problems but are probably safe. GG participated in the design of the review, gave methodological advice, and edited the manuscript. Three placebo-controlled RCTs examined the efficacy of BFRs for the treatment of examination anxiety in students between the ages of 18 and Acad Med. Preparations list Regulation and prevalence Homeopathy and allopathy Homeoprophylaxis Quackery. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Harms Of the four controlled trials, one did not make any reference to harms of BFRs. For efficacy, we included all prospective studies with a control group. Allow Disallow. Find the perfect partner for your busy lifestyle here. They are strong of will and have much courage when they are convinced of those things that they wish to teach. In illness they struggle on long after many would have given up their duties. These vague inexplicable fears may haunt by night or day. For this reason we included evidence from controlled trials as well as observational studies. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Vohra Our Products. Efficacy of BFRs for examination anxiety Three placebo-controlled RCTs examined the efficacy of BFRs for the treatment of examination anxiety in students between the ages of 18 and Our analysis of the four controlled trials of BFRs for examination anxiety and ADHD indicates that there is no evidence of benefit compared with a placebo intervention. -

BOIRON, INC.; and BOIRON USA, INC., 20 21 Judge: Hon

Case 3:11-cv-02039-JAH-NLS Document 64 Filed 03/06/12 Page 1 of 3 LAW OFFICES OF THE WESTON FIRM 1 RONALD A. MARRON, APLC GREGORY S. WESTON (239944) 2 RONALD A. MARRON (175650) [email protected] [email protected] JACK FITZGERALD (257370) 3 MAGGIE. K. REALIN (263639) [email protected] [email protected] COURTLAND CREEKMORE (182018) 4 SKYE RESENDES (278511) [email protected] [email protected] MELANIE PERSINGER (275423) 5 3636 4th Avenue, Suite 202 [email protected] 6 San Diego, California 92103 1405 Morena Blvd., Suite 201 Telephone: (619) 696-9006 San Diego, California 92110 7 Facsimile: (619) 564-6665 Telephone: (619) 798-2006 Facsimile: (480) 247-4553 8 9 Attorneys for Plaintiffs and the Proposed Settlement Class 10 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 SALVATORE GALLUCCI, AMY ARONICA, Case No. 3:11-CV-2039 JAH NLS 14 KIM JONES, DORIS PETTY, and JEANNE Pleading Type: Class Action PRINZIVALLI, individually and on behalf of 15 all others similarly situated, NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION (1) GRANTING PRELIMINARY APPROVAL 16 Plaintiffs, OF CLASS ACTION SETTLMENT, (2) 17 CERTIFYING SETTLEMENT CLASS, (3) APPOINTING CLASS REPRESENTATIVES 18 v. AND LEAD CLASS COUNSEL, (4) APPROVING NOTICE PLAN, AND (5) 19 SETTING FINAL APPROVAL HEARING BOIRON, INC.; and BOIRON USA, INC., 20 21 Judge: Hon. John A. Houston Defendants. Courtroom: 11 (Second Floor) 22 Date: April 30, 2012 _______________________________________ Time: 2:30 p.m. 23 AND ALL RELATED ACTIONS 24 25 26 27 28 Gallucci v. Boiron, Inc., et al., Case No.