Beatitude Magazine and the 1970S San Francisco Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R0693-05.Pdf

I' i\ FILE NO .._O;:..=5:....:::1..;::..62;;;;..4:..- _ RESOLUTION NO. ----------------~ 1 [Howl Week.] 2 3 Resolution declaring the week of October 2-9 Howl Week in the City and County of San 4 Francisco to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first reading of Allen Ginsberg's 5 classic American poem about the Beat Generation. 6 7 WHEREAS, Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl in San Francisco, 50 years ago in 1955; and 8 ! WHEREAS, Mr. Ginsberg read Howl for the first time at the Six Gallery on Fillmore 9 I Street in San Francisco on October 7, 1955; and 10 WHEREAS, The Six Gallery reading marked the birth of the Beat Generation and the 11 I start not only of Mr. Ginsberg's career, but also of the poetry careers of Michael McClure, 12 Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Philip Whalen; and 13 14 WHEREAS, Howl was published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti at City Lights and has sold 15 nearly one million copies in the Pocket Poets Series; and 16 WHEREAS, Howl rejuvenated American poetry and marked the start of an American 17 Cultural Revolution; and 18 WHEREAS, The City and County of San Francisco is proud to call Allen Ginsberg one 19 of its most beloved poets and Howl one of its signature poems; and, 20 WHEREAS, October 7,2005 will mark the 50th anniversary of the first reading of 21 HOWL; and 22 WHEREAS, Supervisor Michela Alioto-Pier will dedicate a plaque on October 7,2005 23 at the site of Six Gallery; now, therefore, be it 24 25 SUPERVISOR PESKIN BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Page 1 9/20/2005 \\bdusupu01.svr\data\graups\pElskin\iagislatiarlire.soll.ltrons\2005\!lo\l'lf week 9.20,05.6(J-(; 1 RESOLVED, That the San Francisco Board of Supervisors declares the week of 2 October 2-9 Howl Week to commemorate the 50th anniversary of this classic of 20th century 3 American literature. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950S and '60S San

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9:1 (2016), 40-61 40 Radio Transmission Electricity and Surrealist Art in 1950s and ‘60s San Francisco R. Bruce Elder Ryerson University Among the most erudite of the San Francisco Renaissance writers was the poet and Zen Buddhist priest Philip Whalen (1923–2002). In “‘Goldberry is Waiting’; Or, P.W., His Magic Education As A Poet,” Whalen remarks, I saw that poetry didn’t belong to me, it wasn’t my province; it was older and larger and more powerful than I, and it would exist beyond my life-span. And it was, in turn, only one of the means of communicating with those worlds of imagination and vision and magical and religious knowledge which all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists heard and saw and ‘tuned in’ on. Poetry was not a communication from ME to ALL THOSE OTHERS, but from the invisible magical worlds to me . everybody else, ALL THOSE OTHERS.1 The manner of writing is familiar: it is peculiar to the San Francisco Renaissance, but the ideas expounded are common enough: that art mediates between a higher realm of pure spirituality and consensus reality is a hallmark of theopoetics of any stripe. Likewise, Whalen’s claim that art conveys a magical and religious experience that “all painters and musicians and inventors and saints and shamans and lunatics and yogis and dope fiends and novelists . ‘turned in’ on” is characteristic of the San Francisco Renaissance in its rhetorical manner, but in its substance the assertion could have been made by vanguard artists of diverse allegiances (a fact that suggests much about the prevalence of theopoetics in oppositional poetics). -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Mining's Toxic Legacy

Mining’s Toxic Legacy An Initiative to Address Mining Toxins in the Sierra Nevada Acknowledgements _____________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Sierra Fund would like to thank Dr. Carrie Monohan, contributing author of this report, and Kyle Leach, lead technical advisor. Thanks as well to Dr. William M. Murphy, Dr. Dave Brown, and Professor Becky Damazo, RN, of California State University, Chico for their research into the human and environmental impacts of mining toxins, and to the graduate students who assisted them: Lowren C. McAmis and Melinda Montano, Gina Grayson, James Guichard, and Yvette Irons. Thanks to Malaika Bishop and Roberto Garcia for their hard work to engage community partners in this effort, and Terry Lowe and Anna Reynolds Trabucco for their editorial expertise. For production of this report we recognize Elizabeth “Izzy” Martin of The Sierra Fund for conceiving of and coordinating the overall Initiative and writing substantial portions of the document, Kerry Morse for editing, and Emily Rivenes for design and formatting. Many others were vital to the development of the report, especially the members of our Gold Ribbon Panel and our Government Science and Policy Advisors. We also thank the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment and The Abandoned Mine Alliance who provided funding to pay for a portion of the expenses in printing this report. Special thanks to Rebecca Solnit, whose article “Winged Mercury and -

Summary of Results of Charitable Solicitation Campaigns Conducted by Commercial Fundraisers in Calendar Year 2016

SUMMARY OF RESULTS OF CHARITABLE SOLICITATION CAMPAIGNS CONDUCTED BY COMMERCIAL FUNDRAISERS IN CALENDAR YEAR 2016 XAVIER BECERRA Attorney General State of California SUMMARY OF RESULTS OF CHARITABLE SOLICITATION BY COMMERCIAL FUNDRAISERS FOR YEAR ENDING 2016 (Government Code § 12599) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGES SUMMARY 1 - 5 TABLE SUBJECT/TITLE 1 ALPHABETICAL LISTING BY CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION 2 LISTING BY PERCENT TO CHARITY IN DESCENDING ORDER 3 THRIFT STORE OPERATIONS – GOODS PURCHASED FROM CHARITY 4 THRIFT STORE OPERATIONS – MANAGEMENT FEE/COMMISSION 5 VEHICLE DONATIONS – ALPHABETICAL BY CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION 6 COMMERCIAL COVENTURERS – ALPHABETICAL BY CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION California Department of Justice November 2017 SUMMARY Every year Californians provide generous support to a wide array of charities, either directly or through commercial fundraisers that charities hire to solicit donations on their behalf. The term “commercial fundraiser” refers generally to a person or corporation that contracts with a charity, for compensation, to solicit funds. The commercial fundraiser charges either a flat fee or a percentage of the donations collected. By law, commercial fundraisers are required to register with the Attorney General’s Registry of Charitable Trusts and file a Notice of Intent before soliciting donations in California. For each solicitation campaign conducted, commercial fundraisers are then required to file annual financial disclosure reports that set forth total revenue and expenses incurred. This Summary Report is prepared from self-reported information contained in the annual financial disclosure reports filed by commercial fundraisers for 2016 and includes statistics for donations of both cash and used personal property (such as clothing and vehicles) for the benefit of charity. Only information from complete financial reports received before October 20, 2017 is included. -

Dana Young Archive Featuring Brion Gysin, Charles Henri Ford, Ira Cohen, Ray Johnson, David Rattray, Harold Norse, and the Bardo Matrix

Dana Young Archive Featuring Brion Gysin, Charles Henri Ford, Ira Cohen, Ray Johnson, David Rattray, Harold Norse, and the Bardo Matrix. [top] A portrait of Dana Young in front of an altar of candles, Kathmandu (date and photographer unknown). [bottom] Detail of Dana Young cover for Ira Cohen’s Poem for La Malinche (Bardo Matrix, ca. 1974) and [right] Dana Young print of Ira Cohen, “The Master & the Owl,” (date unknown). Dana Young (ca. 1948–1979) Dana Young was an essential member of the Kathmandu psychedelic expatriate community of poets, musicians, artists, and spiritual seekers in the 1970s. His poetry and shamanic art blended Eastern spiritual imagery with American pop and consumer culture. He was an active member of the Bardo Matrix collective and is best known for his book Opium Elementals (Bardo Matrix, 1976) that features his beautiful woodblock prints along with two poems by Ira Cohen. He contributed to several other Bardo Matrix publications including Cohen’s Blue Oracle broadside (1975), the frontispiece to Paul Bowles’ Next to Nothing (1976), and Ira Cohen and Roberto Francisco Valenza’s Spirit Catcher! broadside (1976). His artwork also appears in publications such as Montana Gothic (1974) and Ins and Outs (1978). Dana designed the logo (included in the archive) for John Chick’s Rose Mushroom club located at the end of Jhochhen Tole, known as “Freak Street,” in Kathmandu. Most recently, one of Dana Young’s wood block prints was featured on the album cover of the recent release of Angus MacLise's Dreamweapon II. Materials in the present collection comprise the archive of Dana Young supplemented with letters, photographs, and assorted items from the Ira Cohen archive via Richard Aaron, Am Here Books. -

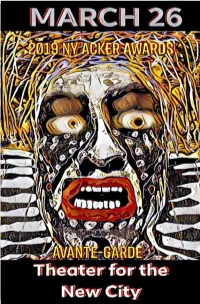

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

City Lights Pocket Poets Series 1955-2005: from the Collection of Donald A

CITY LIGHTS POCKET POETS SERIES 1955-2005: FROM THE COLLECTION OF DONALD A. HENNEGHAN October 2005 – January 2006 1. Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Pictures of the Gone World. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1955. Number One 2. Kenneth Rexroth, translator. Thirty Spanish Poems of Love and Exile. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Two 3. Kenneth Patchen. Poems of Humor & Protest. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Three 4. Allen Ginsberg. Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Four 5. Marie Ponsot. True Minds. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. Number Five 6. Denise Levertov. Here and Now. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1957. Number Six 7. William Carlos Williams. Kora In Hell: Improvisations. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1957. Number Seven 8. Gregory Corso. Gasoline. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1958. Number Eight 9. Jacques Prévert. Selections from Paroles. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1958. Number Nine 10. Robert Duncan. Selected Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1959. Number Ten 11. Jerome Rothenberg, translator. New Young German Poets. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1959. Number Eleven 12. Nicanor Parra. Anti-Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1960. Number Twelve 13. Kenneth Patchen. The Love Poems of Kenneth Patchen. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Number Thirteen 14. Allen Ginsberg. Kaddish and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Number Fourteen OUT OF SERIES Alain Jouffroy. Déclaration d’Indépendance. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1961. Out of Series 15. Robert Nichols. Slow Newsreel of Man Riding Train. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1962. -

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Artaud in Performance: Dissident Surrealism and the Postwar American Avantgarde

Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American avant-garde Article (Published Version) Pawlik, Joanna (2010) Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American avant-garde. Papers of Surrealism (8). pp. 1-25. ISSN 1750-1954 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/56081/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk © Joanna Pawlik, 2010 Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American literary avant-garde Joanna Pawlik Abstract This article seeks to give account of the influence of Antonin Artaud on the postwar American literary avant-garde, paying particular attention to the way in which his work both on and in the theatre informed the Beat and San Francisco writers’ poetics of performance. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M.