+Roo\Zrrg V ,Qgldq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity Presents

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity presents Friday Film Series 2012-2013: Exploring Social Justice Through Film All films begin at 12:00 pm on the Chicago campus. Due to the length of most features, we begin promptly at noon! All films screened in Daniel Hale Williams Auditorium, McGaw Pavilion. Lunch provided for attendees. September 14 – Reel Injun by Neil Diamond (Cree) http://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/ Reel Injun is an entertaining and insightful look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema. Travelling through the heartland of America and into the Canadian North, Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond looks at how the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding – and misunderstanding – of Natives. With clips from hundreds of classic and recent films, and candid interviews with celebrated Native and non-Native directors, writers, actors, and activists including Clint Eastwood, Robbie Robertson, Graham Greene, Adam Beach, and Zacharias Kunuk, Reel Injun traces the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to present day. October 19 – Becoming Chaz by Fenton Bailey & Randy Barbato http://www.chazbono.net/becomingchaz.html Growing up with famous parents, constantly in the public eye would be hard for anyone. Now imagine that all those images people have seen of you are lies about how you actually felt. Chaz Bono grew up as Sonny and Cher’s adorable golden-haired daughter and felt trapped in a female shell. Becoming Chaz is a bracingly intimate portrait of a person in transition and the relationships that must evolve with him. -

PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] Visit the PBS pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: http://www.pbs.org/pressroom/ PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour A Provocative and Entertaining Look at the Portrayal of Native Americans in Cinema to Air November 2010 During Native American Heritage Month (San Francisco, CA)—Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond takes an entertaining, insightful, and often humorous look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema and examining the ways that the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding—and misunderstanding—of Natives. Narrated by Diamond with infectious enthusiasm and good humor, Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian is a loving look at cinema through the eyes of the people who appeared in its very first flickering images and have survived to tell their stories their own way. Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian will air nationally on the upcoming season of the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens in November 2010. Tracing the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to today, Diamond takes the audience on a journey across America to some of cinema’s most iconic landscapes, including Monument Valley, the setting for Hollywood’s greatest Westerns, and the Black Hills of South Dakota, home to Crazy Horse and countless movie legends. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Northern Review 43 Fall 2016.Indd

Exploring human experience in the North research arƟ cle “Indigenizing” the Bush Pilot in CBC’s ArcƟ c Air Renée Hulan Saint Mary’s University, Halifax Abstract When the Canadian BroadcasƟ ng CorporaƟ on (CBC) cut original programming in 2014, it cancelled the drama that had earned the network’s highest raƟ ngs in over a decade. Arc c Air, based on Omni Films’ reality TV show Buff alo Air, created a diverse cast of characters around a Dene bush pilot and airline co-owner played by Adam Beach. Despite its cancellaƟ on, episodes can sƟ ll be viewed on the CBC website, and the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) has conƟ nued broadcasƟ ng the popular show. Through a content analysis of Arc c Air and its associated paratext, read in relaƟ on to the stock Canadian literary fi gure of the heroic bush pilot, this arƟ cle argues that when viewed on the CBC, the program visually “Indigenizes” the bush pilot character, but suggests only one way forward for Indigenous people. On the “naƟ onal broadcaster,” the imagined urban, mulƟ cultural North of Arc c Air—in which Indigenous people are one cultural group among others parƟ cipaƟ ng in commercial ventures—serves to normalize resource development and extracƟ on. Broadcast on APTN, however, where the show appears in the context of programming that represents Indigenous people in a wide range of roles, genres, and scenarios, Arc c Air takes on new meaning. Keywords: media; television; Canadian North; content analysis The Northern Review 43 (2016): 139–162 Published by Yukon College, Whitehorse, Canada yukoncollege.yk.ca/review 139 In 2013, the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) lost the broadcast rights to Hockey Night in Canada, a contract that the private broadcaster Rogers Media secured for $5.2 billion. -

Another Free Educational Program from Young Minds Inspired

AL5692tx:AL5692tx 8/24/07 3:21 PM Page 1 T EACHER’ S G UIDE ANOTHER FREE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM FROM YOUNG MINDS INSPIRED Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee / HBO WHO SHOULD ACTIVITY 1 ESOURCES USE THIS PROGRAM MANIFEST DESTINY – THEN & NOW R This program has been designed Photocopy this list of resources to help students CURRICULUM CONNECTION: This activity examines the role of manifest destiny in for high school and college U.S. with their research. History classes. Please share it the 19th-century displacement of American Indians and in subsequent U.S. domestic and Dear Educator: with other teachers as foreign policy. BOOKS appropriate. Review the material on the activity sheet detailing the role of manifest destiny – the ✜ Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of The heartrending story of the U.S. government's campaign to achieve the attempted subjugation and cultural extermination of the Sioux offers concept that the United States has a “god-given and self-evident right” to dominion of the the American West, by Dee Brown, Owl Books (30th students fertile ground for an honest examination of the building of the American nation—as well as thought-provoking parallels to our world today. Never has PROGRAM continent from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific coast – in justifying the attempted Anniversary Edition), 2001 (orig. pub. 1970) this tragic tale been told as powerfully and realistically as in the new HBO Films® movie Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Following its premiere on COMPONENTS ✜ Black Elk Speaks, by John G. Neihardt, Bison Books, 2004 subjugation of American Indians and their displacement from their traditional tribal lands. -

Cowboys & Aliens :: Rogerebert.Com :: Reviews

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search COWBOYS & ALIENS (PG-13) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » times & tickets in theaters Fandango Search movie The Change-Up showtimes and buy Cowboys & Aliens The Devil's Double tickets. The Future The Guard BY ROGER EBERT / July 27, 2011 Rise of the Planet of the Apes The Road to Nowhere about us "Cowboys & Aliens" has The Robber without any doubt the most About the site » cockamamie plot I've cast & credits more current releases » witnessed in many a moon. one-minute movie reviews Site FAQs » Here is a movie set in 1873 Jake Lonergan Daniel Craig with cowboys, aliens, Woodrow Dolarhyde Harrison Ford Contact us » Apaches, horses, Ella Swenson Olivia Wilde still playing spaceships, a murdering Email the Movie Doc Sam Rockwell Answer Man » stagecoach robber, a Nat Colorado Adam Beach Another Earth preacher, bug-eyed Percy Dolarhyde Paul Dano The Art of Getting By monsters, a bartender Sheriff Taggart Keith Carradine Attack the Block on sale now named Doc, a tyrannical Bad Teacher rancher who lives outside a Beautiful Boy Universal Pictures presents a film town named Absolution, his Beginners directed by John Favreau. Written worthless son, two sexy A Better Life women (one not from by Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman, The Big Uneasy around here), bandits, a Damon Lindelof, Mark Fergus and Bill Cunningham New York Blank City magic bracelet, an ancient Hawk Ostby, based on Platinum Studios' “Cowboys and Aliens” by Bride Flight Indian cure for amnesia, a Bridesmaids Scott Mitchell Rosenberg. -

Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives Through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Michigan Technological University Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2014 Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster Robert D. Hunter Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons Copyright 2014 Robert D. Hunter Recommended Citation Hunter, Robert D., "Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster", Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2014. https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds/746 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons RECLAIMING INDIGENOUS NARRATIVES THROUGH CRITICAL DISCOURSES AND THE AUTONOMY OF THE TRICKSTER By Robert D. Hunter A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In Rhetoric and Technical Communication MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Robert D. Hunter This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Rhetoric and Technical Communication. Department of Humanities Dissertation Advisor: Elizabeth A. Flynn Committee Member: Dieter Wolfgang Adolphs Committee Member: Kette Thomas Committee Member: -

Hollywood Indian Sidekicks and American Identity

Essais Revue interdisciplinaire d’Humanités 10 | 2016 Faire-valoir et seconds couteaux Hollywood Indian Sidekicks and American Identity Aaron Carr and Lionel Larré Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/essais/3768 DOI: 10.4000/essais.3768 ISSN: 2276-0970 Publisher École doctorale Montaigne Humanités Printed version Date of publication: 15 September 2016 Number of pages: 33-50 ISBN: 978-2-9544269-9-0 ISSN: 2417-4211 Electronic reference Aaron Carr and Lionel Larré, « Hollywood Indian Sidekicks and American Identity », Essais [Online], 10 | 2016, Online since 15 October 2020, connection on 21 October 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/essais/3768 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/essais.3768 Essais Hollywood Indian Sidekicks and American Identity Aaron Carr & Lionel Larré Recently, an online petition was launched to protest against the casting of non-Native American actress Rooney Mara in the role of an Indian character in a forthcoming adaptation of Peter Pan. An article defending the petition states: “With so few movie heroes in the US being people of color, non-white children receive a very different message from Hollywood, one that too often relegates them to sidekicks, villains, or background players.”1 Additional examples of such outcries over recent miscasting include Johnny Depp as Tonto in The Lone Ranger (2013), as well as, to a lesser extent, Benicio Del Toro as Jimmy Picard in Arnaud Desplechins’s Jimmy P.: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian (2013).2 Neither the problem nor the outcry are new. Many studies have shown why the movie industry has often employed non-Indian actors to portray Indian characters. -

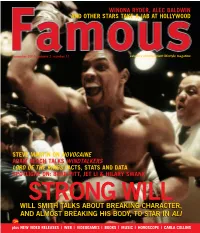

Will Smith Talks About Breaking Character, And

WINONA RYDER, ALEC BALDWIN AND OTHER STARS TAKE A JAB AT HOLLYWOOD november 2001 volume 2 number 11 canada’s entertainment lifestyle magazine STEVE MARTIN ON NOVOCAINE ADAM BEACH TALKS WINDTALKERS LORD OF THE RINGS FACTS, STATS AND DATA SPOTLIGHT ON: BRAD PITT, JET LI & HILARY SWANK STRONG WILL WILLWILL SSMITHMITH TATALKSLKS AABOUTBOUT BREAKINGBREAKING CHARACTER,CHARACTER, ANDAND ALMOSTALMOST BREAKINGBREAKING HISHIS BODY,BODY, TOTO STARSTAR ININ ALALII $300 plus NEW VIDEO RELEASES| WEB| VIDEOGAMES | BOOKS | MUSIC | HOROSCOPE | CARLA COLLINS contents Famous | volume 2 | number 11 | 22 31 FEATURES COLUMNS 22 THREE RINGS CIRCUS 12 HEARSAY Opening night for The Fellowship of Heidi Fleiss’s Hollywood beau the Ring is so close you can almost hear the Black Riders approaching. 40 LINER NOTES Here we give you 54 facts about next Chris Sheppard, still tending his flock month’s big flick and the rest of the Lord of the Rings trilogy 42 PULP AND PAPER 24 New grub for bookworms 24 ON THE BEACH You know him as that good-looking 44 BIT STREAMING guy from just about every Canadian DEPARTMENTS Do-it-yourself Star Wars renovations production that has anything to do with native people. Soon the whole world 08 EDITORIAL 46 NAME OF THE GAME will know him as Nicolas Cage’s co-star Reviewing Xbox, Gamecube and PS2 in the World War Two drama Windtalkers. 11 LETTERS We dive into the psyche of Adam Beach By Sean Davidson 14 SHORTS November film fests 20 31 STEVE-ADORE Joking about the perils of low-budget 16 THE BIG PICTURE pics, rumours that he’s gay and Monsters, Inc., Shallow Hal and co-star/former flame Helena Bonham Harry Potter storm theatres Carter, Steve Martin had journalists eating out of the palm of his hand at a 20 THE PLAYERS press conference for his new dentistry Everything you need to know about thriller Novocaine By Marni Weisz Jet Li, Brad Pitt and Hilary Swank COVER STORY 32 TRIVIA 34 MUHAMMAD ALI’S WILL 36 COMING SOON Why did Will Smith get the role of Muhammad Ali over Oscar-winners like 38 ON THE SLATE Cuba Gooding Jr. -

A Star Attraction the Evening Also Included Traditional Charitable Organization Formed Through Convention Centre

That’s A Wrap! Our New Team More than 500 attended the Gala Vision Quest Conferences Inc. welcomes Banquet on closing night – the most our new 2009 coordination team: popular event of the conference each year. Conference Coordinators: People dressed up in their best and came Debbie Maslowsky and Melanie Rennie out to indulge in a delicious dinner, cel- ebrate achievement, share in special hon- Administrative Assistant/Bookkeeper: ourings, and enjoy entertainment. Jocelyn Lobster DerRic Starlight is a comedian and pup- Ph: (204) 942-5049 / 1-800-557-8242 peteer who amazes audiences from Fax: (204) 943-1735 around the world. He surely amazed the E-mail: [email protected] Vision Quest crowd, and had the whole room laughing when Grand Chief Morris Shannacappo joined him and his puppet Special Thanks The 12th annual Vision Quest Conference Granny on stage. Vision Quest Conferences Inc. is a non-profit took place May 13 to 15 at the Winnipeg A Star Attraction The evening also included traditional charitable organization formed through Convention Centre. This year’s event was the dancing and drums performed by Curtis partnerships with six Community Futures largest to date, with nearly 600 registered Assiniboine and family, a video sum- Development Corporations: Delegates – including 177 youth – and a very mary of the 2008 conference, and a Cedar Lake CFDC; Dakota Ojibway CFDC; performance by Reddnation, Canada’s Kitayan CFDC; Northwest CFDC; busy tradeshow presenting 82 Exhibitors. Aboriginal rap sensation. Reddnation also North Central CFDC; and Southeast CFDC Thank you to everyone for participating. It conducted two popular youth workshops Therefore, Vision Quest would not exist with- wouldn’t have been a success without you! at the conference – Anti Gang Awareness, out the generous support of our Sponsors. -

Native American Music Awards Honor Grand Ronde Tribal Member Jan Michael "Looking Wolf" Reibach Was Thrilled to Compete Though He Did Not Win

MARCH 1, 2005 Smoke Signals Native American Music Awards Honor Grand Ronde Tribal Member Jan Michael "Looking Wolf" Reibach was thrilled to compete though he did not win. By Ron Karten night was Tribal mem- "I felt pretty good about it," said "Native music not only survives," ber Jan Michael "Look- Kennedy. "I said, "Wow,' we're nomi- said Jimmy Lee Young. "It grows and ing Wolf Reibach, nom- nated. Even though we didn't win, Fm it thrives!" inated his first time out just going to keep doing what I'm do- I le accepted the 2005 Native Ameri- for a NAMMY in the ing." can Music Award (NAMMY) for best BluesJazz category. "It is an honor to be recognized by Single ofthe Year: One Voice One Cry. On his excitement the Native American Music Awards "It starts with the Creator," said level before the show, and I am so thankful to everyone for Litefoot, who took home the NAMMY Reibach rated it at, their support," wrote Reibach. "Also, for Artist of the Year. "I was told I "Way!" Afterwards, I appreciate the guitar tracks by would never do anything for my people when the award went to Vernon Kennedy and Michael "Stand- with rap," he added, now vindicated. Cecil Gray & Red Dawn ing Elk" Reibach. Their talents con- After the NAMMYs, Litefoot was to Blues Band for their CD, tributed greatly to the CD's success." start on a 40-stat- e, Indian Harmony, Standout performances between tour in support of his album, Native Reibach started looking awards came from Li'l Dre (Navajo), American Me. -

Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives Through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2014 Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster Robert D. Hunter Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons Copyright 2014 Robert D. Hunter Recommended Citation Hunter, Robert D., "Reclaiming Indigenous Narratives through Critical Discourses and the Autonomy of the Trickster", Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2014. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/746 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Rhetoric Commons RECLAIMING INDIGENOUS NARRATIVES THROUGH CRITICAL DISCOURSES AND THE AUTONOMY OF THE TRICKSTER By Robert D. Hunter A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In Rhetoric and Technical Communication MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Robert D. Hunter This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Rhetoric and Technical Communication. Department of Humanities Dissertation Advisor: Elizabeth A. Flynn Committee Member: Dieter Wolfgang Adolphs Committee Member: Kette Thomas Committee Member: Latha Poonamallee Department Chair: Ronald Strickland 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................