How Lego Became the Apple of Toys After a Decade-Long Slump, Lego Has Rebuilt Itself Into a Global Juggernaut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

The LEGO Trains Book Choose Scale, Wheels, Motors, and Track Layout

Shelve in: hobbieS/lego • FOR AGES 10+ TH ® BRING YOUR MODEL RAILROAD TO LIFE! E Learn the model-making process from start to finish, including the best ways to LEGO THE LEGO TRAINS BOOK choose scale, wheels, motors, and track layout. Get advice for building steam engines, locomotives, and passenger cars, and discover fresh ideas and inspiration ® for your own LEGO train designs. ® T INSIDE You’ll find RAINS BOOK • A historical tour of LEGO trains • Advice on advanced building tech- • Step-by-step building instructions for niques like SNOT (studs not on top), models of the German Inter-City Express micro striping, creating textures, and (ICE), the Swiss “Crocodile,” and a making offset connections vintage passenger car • Case studies of the design process • Tips for controlling your trains with • Ways to use older LEGO pieces transformers, receivers, and motors in modern designs HOLGER MATT PRICE: $24.95 ($33.95 CDN) THE FINEST IN GEEK ENTERTAINMENT™ www.nostarch.com This book is not authorized or endorsed by the LEGO Group. H ES HOLGER MATTHES INDEX Numbers fixed, 81–82 Brickset website, 5–6 controllers (Power Functions Era), 4D Brix, 106 leading, 89, 128 BrickTracks, 106 37, 40 4.5 V battery-powered system trailing, 89, 128 buffers corridor connectors, 101–102 Blue Era, 18 couplings Blue Era, 13–14, 19 B Gray Era, 21, 26 couplings and, 84–87 Blue Era, 18 ballasting track, 106–107 6-wide scale, 75–76 Gray Era, 25 Gray Era, 25 bars, 48, 50 7-wide scale, 76–77 building instructions, 134 tracks, 84–87 bases 8-wide scale, 77–78 Inter-City -

Packaging Copy Final

U.S. STANDARD PACKAGING COPY FINAL ARTIST: Various RELEASE DATE: July 15, 2016 TITLE: Ghostbusters Original Motion Picture Soundtrack Compact Disc Album Selection No. 88985-32812-2 Digital Album Selection No. G0100035314741 IMPRINT LABEL: RCA Records/Columbia Pictures FRONT COVER Ghostbusters Original Motion Picture Soundtrack SPINES 88985-32812-2 [INSERT LOGOS] RCA RETRO, COLUMBIA PICTURES Ghostbusters Original Motion Picture Soundtrack TRAY CARD, REAR PANEL Ghostbusters Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 01 Ghostbusters WALK THE MOON [USRC11601201] 3:45 02 Saw It Coming G-Eazy X Jeremih [USRC11601122] 3:30 03 Good Girls Elle King [USRC11601121] 2:59 04 Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds Of Summer [GBUM71603113] 3:36 05 wHo ZAYN* [USRC11601202] 2:55 06 Ghostbusters Pentatonix* [USRC11601203] 2:53 07 Ghoster Wolf Alice* [GBK3W1600481] 2:31 08 Ghostbusters (I’m Not Afraid) Fall Out Boy feat. Missy Elliott [US4DG1600451] 3:06 09 Get Ghost Mark Ronson, Passion Pit & A$AP Ferg [GBARL1600808] 3:37 10 Party Up (Up In Here) DMX [USDJ20010705] 4:31 11 Rhythm Of The Night DeBarge [USMO18500526] 3:51 12 American Woman Muddy Magnolias [USUM71508112] 3:01 13 Want Some More Beasts Of Mayhem [US4DG1600452] 2:04 14 Ghostbusters Ray Parker Jr. [QZ4KE1600002] 4:05 Executive Album Producers: Paul Feig, Amy Pascal, Peter Edge & Tom Corson Music Supervisor: Erica Weis Executive in Charge of Music for Sony Pictures: Lia Vollack Executive in Charge of Music for RCA Records: Karen Lamberton * DOES NOT APPEAR IN FILM ghostbusters.com twitter & instagram: @ghostbusters facebook.com/ghostbusters rcarecords.com [INSERT DOMESTIC BILLING BLOCK] [INSERT BARCODE] 88985-32812-2 [INSERT LOGOS] RCA RETRO, COLUMBIA PICTURES, FBI LOGO [INSERT] FBI ANTI-PIRACY WARNING: UNAUTHORIZED COPYING IS PUNISHABLE UNDER FEDERAL LAW. -

Building Buildings with Jonathan Lopes! 1964 World’S Fair Villa Amanzi

The Magazine for LEGO® Enthusiasts of All Ages! Issue 30 • August 2014 $8.95 in the US Building Buildings with Jonathan Lopes! 1964 World’s Fair Villa Amanzi Instructions 0 7 AND MORE! 0 74470 23979 6 Issue 30 • August 2014 Contents From the Editor ..................................................2 People/Building Villa Amanzi: LEGO Modeling a Luxury Thai Villa ...3 Urban Building ................................................11 You Can Build It: Truck and Trailer ...........................................17 Anuradha Pehrson: Childhood Interest, Adult Passion ...21 The Chapel of the Immaculate Conception......................................................29 Building a Community Brick by Brick ...................................................33 Building Copenhagen ...............................40 Rebuilding the 1964 World’s Fair .......46 You Can Build It: New York Pavilion, 1964 World’s Fair .........................................51 BrickNerd’s DIY Fan Art: Bronson Gate ................................................54 You Can Build It: Endor Shield Generator Bunker ......62 MINDSTORMS 101: Programming Turns for Your Robot................................................68 Minifigure Customization 101: Jared Burks: A History of a Hobby and a Hobbyist..............................................70 Community LEGO Ideas: Getting the Word Out: QR Codes ....74 An Interesting Idea: Food Truck........76 Community Ads.............................................78 Last Word .............................................................79 -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

21034 London Great Britain London

21034 London Great Britain London Originally founded by the Romans over 2,000 years ago, culturally diverse; more than 300 languages are spoken by London has grown to become the cultural and economic its population of over 8.5 million people. capital of Britain and one of the world’s truly global cities. Standing on the River Thames, London’s skyline reflects Famous for its finance, fashion and arts industries, London both the city’s diverse and colorful past and its continued is the world’s most visited city and also one of its most ambition to embrace bold, modern architectural statements. [ “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.” ] Samuel Johnson 2 3 The National Gallery From the very start, the aim of the National Gallery was to ensure that the widest public possible could enjoy its collection. When Parliament agreed to pay for the construction of a new gallery in 1831, there were lengthy discussions about where the building should be located. Trafalgar Square was eventually chosen, as it was considered to be at the very center of the city and therefore accessible by all classes of London society. Construction began in 1832 and the new gallery was finally completed in 1838. The building has been enlarged and altered many times as the National Gallery’s collection grew and today holds over 2,300 works of art. Over six million people visit the Gallery every year to enjoy works by Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent Van Gogh and J.M.W. -

21034 London Great Britain London

21034 London Great Britain London Originally founded by the Romans over 2,000 years ago, culturally diverse; more than 300 languages are spoken by London has grown to become the cultural and economic its population of over 8.5 million people. capital of Britain and one of the world’s truly global cities. Standing on the River Thames, London’s skyline reflects Famous for its finance, fashion and arts industries, London both the city’s diverse and colorful past and its continued is the world’s most visited city and also one of its most ambition to embrace bold, modern architectural statements. [ “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.” ] Samuel Johnson 2 3 The National Gallery From the very start, the aim of the National Gallery was to ensure that the widest public possible could enjoy its collection. When Parliament agreed to pay for the construction of a new gallery in 1831, there were lengthy discussions about where the building should be located. Trafalgar Square was eventually chosen, as it was considered to be at the very center of the city and therefore accessible by all classes of London society. Construction began in 1832 and the new gallery was finally completed in 1838. The building has been enlarged and altered many times as the National Gallery’s collection grew and today holds over 2,300 works of art. Over six million people visit the Gallery every year to enjoy works by Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent Van Gogh and J.M.W. -

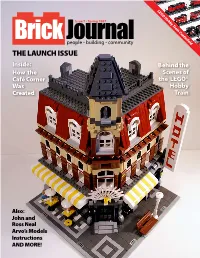

THE LAUNCH ISSUE Inside: Behind the How the Scenes of Café Corner the LEGO® Was Hobby Created Train

LEGO Hobby Train Centerfold THE LAUNCH ISSUE Inside: Behind the How the Scenes of Café Corner the LEGO® Was Hobby Created Train Also: John and Ross Neal Arvo’s Models Instructions AND MORE! Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

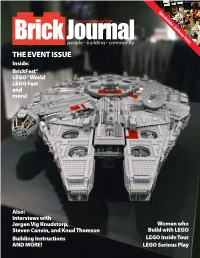

THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: Brickfest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and More!

Epic Builder: Anthony Sava THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: BrickFest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and more! Also: Interviews with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, Women who Steven Canvin, and Knud Thomson Build with LEGO Building Instructions LEGO Inside Tour AND MORE! LEGO Serious Play Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Toy Collection Underway for Children Suffering with Childhood Cancer by MB Gilligan Back Mountain Community News Correspondent

NOVEMBER 2019 Toy collection underway for children suffering with childhood cancer By MB Gilligan Back Mountain Community News Correspondent The family of the late Emily Longmore is commemo- rating what would have been her fifth birthday with a toy collection for children suffering from childhood can- cer. Emily was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, a type of childhood cancer, when she was just three years old. During the time she received treatment, Emily showed remarkable strength and courage. She loved making friends with her nurses and she always had a smile. She was a joy to her parents and her older siblings Ben and Lily. They started Emily’s Gracious Gifts as a means of continuing Emily’s legacy in helping others who are bat- tling childhood cancer. Fino’s Pharmacy in Dallas and the Luzerne Foundation in Wilkes-Barre are the collec- tion sites for new, unwrapped toys for children of all ages and are also accepting donations of Visa and Master Card gift cards or cash. Emily’s family will wrap the items and bring the gifts to Geisinger’s Pediatric Oncology Clinic and the Janet Weis Children’s hospital in Danville on November 28, Emily’s birthday. Items dropped off after that time will also be collected and all items will be distributed dur- ing the Christmas season. For more information you can call 570-822-2065 or email [email protected]. Emily Longmore lost her battle with childhood cancer but her family will honor her fifth birthday with a contribution of gifts for others battling this illness. Community News • November 2019 • Page 2 Third annual Ride for Honor will benefit veterans Dairy Maid visits Sweet Valley Open House The third annual Karen Bo- Sweet Valley back Ride for Honor held on Emergency Services May 26 was another successful recently held an open event in support of local veter- house for the pub- ans’ organizations. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co.