An Overview of Some Vernacular Techniques in Iranian Sustainable Architecture in Reference to Cisterns and Ice Houses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Iran and the Premodern Persianate World, Graduate Specialization 1

Ancient Iran and the Premodern Persianate World, Graduate Specialization 1 Ancient Iran and the Premodern Persianate World, Graduate Specialization Matthew P. Canepa, Director 2000 Humanities Gateway 949-824-3532 [email protected] The graduate specialization in Ancient Iran and the Premodern Persianate World is University of California, Irvine’s interdisciplinary platform for graduate study in premodern Iranian studies. It is designed to provide Ph.D. students with the interdisciplinary training they need to conduct advanced research in the art, archaeology, architecture, history, literatures, and religions of Iran, as well as those peoples, regions, and empires whose destinies were intertwined with Iran, or impacted by its cultures (e.g. ancient Greece and Rome, Armenia, or Islamic Western or South Asia). UCI boasts unparalleled faculty and programmatic resources for the study of ancient Iran and the wider premodern Persianate world, including the highest concentration of endowed chairs in ancient Iranian studies of any North American institution. With especial faculty strengths in ancient Iran, the specialization’s broader historical scope encompasses the Bronze Age cultures of the Iranian Plateau, Mesopotamia, and Central Asia up to the early modern empires of the Mughals, Safavids, and Ottomans (ca. 3500 BCE – ca. 1740 CE). The specialization’s broad conception of premodern Iranian Studies is paralleled in, and supported by, the extensive programming of UCI’s Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture (https:// www.humanities.uci.edu/persianstudies/), which provides the primary focus of the specialization’s graduate workshop. Prospective students who wish to pursue a Ph.D. in Iranian Studies at UCI must first apply (https://www.humanities.uci.edu/persianstudies/program/ grad_admit.php) and be admitted to the doctoral program through which their potential advisor accepts students, for example, the Ph.D. -

The Phylogeny of the Eremias Velox Complex of the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia (Reptilia, Lacertidae): Molecular Evidence from ISSR-PCR Fingerprints

Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics(IJAB) Vol.5, No.1, 33-46, 2009 ISSN: 1735-434X The phylogeny of the Eremias velox complex of the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia (Reptilia, Lacertidae): Molecular evidence from ISSR-PCR fingerprints ESKANDAR RASTEGAR POUYANI Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Tarbiat Moallem University of Sabzevar, P.O.Box, 397, Iran The rapid fringe-toed lizard, Eremias velox, is widely distributed in the Iranian plateau and Central Asia. Several local morphotypes have so far been reported from different parts of its range, representing this taxon as a species complex. In an attempt to reveal phylogenetic relationships among various populations of this complex group, 37 specimens from 13 geographically distant localities in Iran and central Asia, covering most parts of its range, were sampled. Using Inter Simple Sequence Repeat amplification (ISSR-PCR) as a molecular marker, whole the nuclear genome of all specimens was screened. Phylogenetic analysis of the prepared data set successfully recovered seven major clades within the E. velox complex. Relationships among the major clades were highly resolved with remarkable statistical supports and well correspond to the geographic distribution of the populations. The reconstructed phylogeny implies that the clade as a whole has been originated in the Iranian plateau and expanded into central Asia before uplifting the Kopet-Dagh Mountains. It has then undergone a rapid cladogenesis in the latter area and produced several morphotypes. Within the Iranian clades two main groups could be defined, the foothill and highland dwellers and the open plane and desert dweller populations. The phylogenetic tree together with the estimated amounts of genetic distances among the independent lineages, provide good grounds for a fundamental revision of the taxonomic status of the Eremias velox complex. -

Flexural Bending of the Zagros Foreland Basin

Geophysical Journal International Geophys. J. Int. (2017) 210, 1659–1680 doi: 10.1093/gji/ggx252 Advance Access publication 2017 June 9 GJI Geodynamics and tectonics Flexural bending of the Zagros foreland basin Mortaza Pirouz,1,2 Jean-Philippe Avouac,1 Adriano Gualandi,1 Jamshid Hassanzadeh1 and Pietro Sternai3 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Mc 100–23, 1200 E California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91125, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Bullard Laboratories, Madingley Rise, Madingley Road, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB30EZ, United Kingdom 3Section of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Geneva, 13 Rue des Maraˆıchers, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland Accepted 2017 June 7. Received 2017 June 5; in original form 2017 February 24 SUMMARY We constrain and model the geometry of the Zagros foreland to assess the equivalent elastic thickness of the northern edge of the Arabian plate and the loads that have originated due to the Arabia–Eurasia collision. The Oligo-Miocene Asmari formation, and its equivalents in Iraq and Syria, is used to estimate the post-collisional subsidence as they separate passive margin sediments from the younger foreland deposits. The depth to these formations is obtained by synthesizing a large database of well logs, seismic profiles and structural sections from the Mesopotamian basin and the Persian Gulf. The foreland depth varies along strike of the Zagros wedge between 1 and 6 km. The foreland is deepest beneath the Dezful embayment, in southwest Iran, and becomes shallower towards both ends. We investigate how the geometry of the foreland relates to the range topography loading based on simple flexural models. -

The Effect of the Zagros Mountains on the Formation and Maintenance of the Iran Anticyclone Using Regcm4

Meteorol Atmos Phys (2011) 112:91–100 DOI 10.1007/s00703-011-0134-z ORIGINAL PAPER The effect of the Zagros Mountains on the formation and maintenance of the Iran Anticyclone using RegCM4 Azar Zarrin • Hooshang Ghaemi • Majid Azadi • Abbas Mofidi • Ebrahim Mirzaei Received: 4 May 2010 / Accepted: 16 March 2011 / Published online: 24 April 2011 Ó Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract Iran anticyclone is one of the main features of total heating. In the absence of the Zagros Mountains, the the summer circulation over the Middle East in the middle vertical advection and the mid-troposphere anticyclonic and upper troposphere. To examine the effect of the Zagros circulation are apparently weak and, therefore, the Iran Mountains on the formation and maintenance of the Iran subtropical anticyclone vanishes over the west of Iran. The anticyclone, an experiment was conducted by Regional study indicates that the Zagros Mountains as an elevated Climate Model (RegCM4) in an area between 22°–44°N heat source have the main impact in the formation of a and 35°–70°E with a 40 km horizontal grid spacing. The thermally driven circulation over the Middle East. NCEP/NCAR re-analysis data set were used to provide the initial and lateral boundary conditions in a control run and in a simulation run by removing the Zagros Mountains. The 1 Introduction result reveals that the Zagros Mountains have an important effect on the formation and maintenance of the low-level The nature of subtropical anticyclones and their formation cyclonic circulation and mid-level anticyclonic circulation mechanism has been one of the most challenging subjects in summer. -

Anthropological and Genetic Characteristics of Atropatene Population

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 5; March 2012 Anthropological and Genetic Characteristics of Atropatene population Vahid Rashidvash Department of Iranian Studies Yerevan State University, Yerevan Armenia Abstract Iran is of great interest to a wide range of scientific disciplines because of the rich ethnic and cultural diversity of population living there, and the extreme complexity of the historical and genetic issues in the region. However, studies related to the ethnogenesis of indigenous peoples and their ancient genetic contacts are not conclusive. Iranian Azaris – the largest ethno-linguistic minority in Iran – are one of such peoples. The origin of the Turkic- speaking population of the north-western provinces of Iran, the so-called Azaris, is the subject of long-year debate. In this paper the anthropological data obtained by the author and the genetic results of modern scientific literature, concerning the ethnogenesis of Iranian Azaris, which is essential addition to their historical, archaeological and ethnographic. The main conclusion of the work, which is based on the analysis of anthropometric and genetic material, is as follows: the ethnic group under consideration - Iranian Azaris, undoubtedly is the indigenous population in the region of the Middle East. Key words : Iranian Azersi . Persians. Atropatgan . Genetic Origin. Multivariate analysis Introduction Due to its geo-strategic location in the Middle East, the Iranian plateau has served as a key crossroad for human disseminations and played a critical role in the migratory waves between the populations of the Middle East and beyond. The most important long-term factor in this process was human adaptation to the Iranian plateau and its geographical, topographical, and climatic conditions with the subsequent development of agriculture, pastoralism, and pastoral nomadism. -

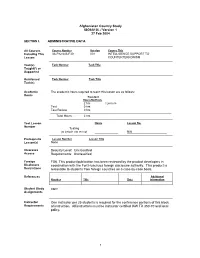

Appendix H- Afghanistan Overview Program of Instruction

Afghanistan Country Study ISO6A10L / Version 1 27 Feb 2004 SECTION I. ADMINISTRATIVE DATA All Courses Course Number Version Course Title Including This 3A-F82/243-F30 001 INTELLIGENCE SUPPORT TO Lesson COUNTERTERRORISM Task(s) Task Number Task Title Taught(*) or Supported Reinforced Task Number Task Title Task(s) Academic The academic hours required to teach this lesson are as follows: Hours Resident Hours/Methods 2 hrs / Lecture Test 0 hrs Test Review 0 hrs Total Hours: 2 hrs Test Lesson Hours Lesson No. Number Testing (to include test review) N/A Prerequisite Lesson Number Lesson Title Lesson(s) None Clearance Security Level: Unclassified Access Requirements: Unclassified Foreign FD6. This product/publication has been reviewed by the product developers in Disclosure coordination with the Fort Huachuca foreign disclosure authority. This product is Restrictions releasable to students from foreign countries on a case-by-case basis. References Additional Number Title Date Information Student Study none Assignments Instructor One instructor per 25 students is required for the conference portions of this block Requirements of instruction. All instructors must be instructor certified IAW TR 350-70 and local policy. 1 Additional Stu Support Name Ratio Qty Man Hours Personnel None Requirements Equipment Id Stu Instr Required Name Ratio Ratio Spt Qty Exp for Instruction 6730-01-T08-4239 25:1 1:25 No 1 No Projector LitePro * Before Id indicates a TADSS Materials Instructor Materials: Required Course Introduction, Lesson Plan, and Slideshow. Student Materials: Notebook and pen. Classroom, CLASSROOM, GEN INSTRUCTION, 1000 SQ FT, 30 PN Training Area, and Range Requirements Ammunition Stu Instr Spt Requirements Id Name Exp Ratio Ratio Qty None Instructional NOTE: Before presenting this lesson, instructors must thoroughly prepare by studying this Guidance lesson and identified reference material. -

Crustal Structure of a Young Collision Zone

Hacıoğlu et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2018) 70:161 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-018-0932-3 FULL PAPER Open Access Crustal structure of a young collision zone: the Arabia–Eurasia collision in northeastern Turkey investigated by magnetotelluric data Özlem Hacıoğlu1,2* , Ahmet Tuğrul Başokur3 and Elif Tolak Çiftçi1 Abstract The northeastern Turkey is located at the intensely deformed east Anatolian Collision Zone that is formed by the collision of the Arabian Plate with Eurasia. The region is one of the best examples of the continental collision zone in the world and exhibits an active north–south shortening and a young and widespread volcanism. In northeastern Anatolia, the ongoing motions of the Arabian and Eurasian Plates through a range of deformation processes have generated the Erzurum–Kars Plateau, a region of large-scale deformation and uplift observed at surface. However, the nature of deformation driven by the continental collision remains unresolved at depth. In this study, magnetotelluric (MT) data recorded at 74 sites constituting two intersecting profles have been used to construct the characteristic electrical conductivity pattern associated with the intensely deformed east Anatolian Collision Zone beneath the Erzurum–Kars Plateau, northeastern Turkey, with the aim of imaging the 3D distribution of fuids in order to link it with subsurface rheological conditions. An equal number of colocated transient electromagnetic (TEM) sounding data were used to allow the static shift correction of the MT data; a borehole was also drilled inside the study area. We ran a one-dimensional inversion of TEM data in order to determine shift in MT data and a three-dimensional inversion using full components of MT impedance tensor previously corrected for static shift. -

New Seismic Array Observation in the Northwestern Iranian Plateau

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 18, EGU2016-3427, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. New Seismic Array Observation in the Northwestern Iranian Plateau Ling Chen (1,2), Mingming Jiang (1,2), Morteza Talebian (3), Abdolreza Ghods (4), Sun-Lin Chung (5), Yinshuang Ai (1,2), Farhad Sobouti (4), Yumei He (1), Khalil Motaghi (4), Tianyu Zheng (1), Mohammad Faridi (6), Qi-Fu Chen (1), Yan Lyu (1), Wenjiao Xiao (1,2), Morteza Khalatbari Jafari (3), and Rixiang Zhu (1) (1) State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS), Beijing, China, (2) CAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Beijing, China, (3) Research Institute for Earth Sciences, Geological Survey of Iran (RIESGSI), Tehran, Iran, (4) Department of Earth Sciences, Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences (IASBS), Zanjan, Iran, (5) Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica & Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, (6) Geological Survey of Iran, Northwestern Regional Office, Tabriz, Iran The Iranian Plateau, being formed as a consequence of the on-going Arabia-Eurasia collision, is a natural labo- ratory for understanding mountain/plateau building processes and deep dynamics related to the early phases of continent-continent collision. A key issue in the study of the Iranian Plateau is to acquire detailed information about the structure and deformation of the crust and mantle. For this purpose, we (IGGCAS, RIESGSI, IASBS) deployed a new temporary broadband seismic array in NW Iran, under a multidisciplinary collaborative project named “China-Iran Geological and Geophysical Survey in the Iranian Plateau (CIGSIP)”. -

Language Shift in the Central Iranian Plateau

Journal of Persianate Studies 2 (2009) 62-87 brill.nl/jps Median Succumbs to Persian after Th ree Millennia of Coexistence: Language Shift in the Central Iranian Plateau Habib Borjian Abstract Th e so-called Central Plateau Dialects or simply Central Dialects belong to the South Median group of Northwest Iranian languages and are spoken in central Iran, where the prevailing lan- guage is Persian. Currently, vestiges of these dialects are limited to several dozen remote villages as well as to the older generation of the Jewish and Zoroastrian communities living in the cities and in diaspora. Th e dominant infl uence of Persian for more than a millennium has resulted in the ousting of the vernaculars not only in major towns but also in a majority of villages. His- torical evidence suggests that Central Dialects were native to the entire central Iranian Plateau, larger towns included, until the late medieval period. Th e big shift may have taken place during and after the Safavid dynastic rule, perhaps as a result of forceful propagation of Shiʿism, among other economic and socio-political vicissitudes of those days. Concrete evidence becomes avail- able only in the later nineteenth century when European travelers and local geographers began to report on the language situation of the area. Th ese documents enable us to speculate on the patterns and rates of language shift in various regions speaking Central Dialects. Th is trend has been accelerating parallel with the enormous socio-economic changes in the last half century. In many villages the local dialect is moribund and becoming increasingly limited to the elders, and the extinction will be the inevitable result of the forces of modernization and globalization in general and the rapid expansion of Persian education and mass media in particular. -

Book WARD.Indb

Nest of the Phoenix GEORGIA T'bilisi Caspian ARM. Sea Yerevan AZERBAIJAN Baku TURKMENISTAN Tabriz Ashgabat K Lake o p p Rasht e h Urmia D a A s g h Zanjan l b o a i n Arbil r z M o u n t Mashhad Kirkuk Z Tehran a Qom g Dasht-e Kavir Kermanshah r Arak Herat o Baghdad s M Esfahan IRAN D o a AFGHANISTAN s IRAQ u h Ahvaz n t - t e a i L Abadan n u Al Basrah s Kerman t Shiraz Zahedan Kuwait KUWAIT Bushehr PAKISTAN Persian Bandar 'Abbas untains GulfStrait of Bashakerd Mo Hormuz Manama BAHRAIN OMAN Doha Riyadh Abu Dhabi Gulf of Oman QATAR Muscat SAUDI UAE ARABIA Arabian OMAN 0 300 Miles Sea 0 300 Kilometers I.1 Nest of the Phoenix Copyright © 2009 by Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by Georgetown University Press. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of Georgetown University Press. Introduction The Iranian Phoenix IN 1978 IRAN AND ITS ARMED FORCES seemed to stand at the peak of their power and prestige in the modern era. Bountiful oil revenues and a strategic position overlooking the vital Persian Gulf oil export routes boosted Iran’s standing in the world. Cold War competition made Iran a recipient of Western and Soviet arms and att ention. Iran had just passed Egypt, a far more popu- lous country, in having the largest armed forces in the Middle East. In fact, the Iranian military was outpacing some large European countries in the quantity and sophistication of its equipment. -

Mantle-Flow Diversion Beneath the Iranian Plateau Induced by Zagros

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Mantle‑fow diversion beneath the Iranian plateau induced by Zagros’ lithospheric keel Ayoub Kaviani1*, Meysam Mahmoodabadi1,2, Georg Rümpker1, Simone Pilia3, Mohammad Tatar2, Faramarz Nilfouroushan4,5, Farzam Yamini‑Fard2, Ali Moradi6 & Mohammed Y. Ali7 Previous investigation of seismic anisotropy indicates the presence of a simple mantle fow regime beneath the Turkish‑Anatolian Plateau and Arabian Plate. Numerical modeling suggests that this simple fow is a component of a large‑scale global mantle fow associated with the African superplume, which plays a key role in the geodynamic framework of the Arabia‑Eurasia continental collision zone. However, the extent and impact of the fow pattern farther east beneath the Iranian Plateau and Zagros remains unclear. While the relatively smoothly varying lithospheric thickness beneath the Anatolian Plateau and Arabian Plate allows progress of the simple mantle fow, the variable lithospheric thickness across the Iranian Plateau is expected to impose additional boundary conditions on the mantle fow feld. In this study, for the frst time, we use an unprecedented data set of seismic waveforms from a network of 245 seismic stations to examine the mantle fow pattern and lithospheric deformation over the entire region of the Iranian Plateau and Zagros by investigation of seismic anisotropy. We also examine the correlation between the pattern of seismic anisotropy, plate motion using GPS velocities and surface strain felds. Our study reveals a complex pattern of seismic anisotropy that implies a similarly complex mantle fow feld. The pattern of seismic anisotropy suggests that the regional simple mantle fow beneath the Arabian Platform and eastern Turkey defects as a circular fow around the thick Zagros lithosphere. -

Persian Gulf

UNITED NATIONS Working Paper GROUP OF EXPERTS ON No. 61 GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Twenty-third Session Vienna, 28 March – 4 April 2006 Item 14 of the Provisional Agenda: Activities relating to the Working Group on Exonyms Historical, Geographical and Legal Validity of the Name: PERSIAN GULF Prepared Working Group on Exonyms , Iran Historical, Geographical and Legal Validity of the Name : PERSIAN GULF Introduction Geography, as the most ancient human knowledge is an applied science which has different aspects. It studies the reciprocal relation of man and nature and provides the results to the users in the form of documents in writing, books and maps. The names of features and phenomena including natural or man made ones have been considered by geographers for a long time, therefore similar features are distinguished by it. The name of a feature can not be observed on the land like the feature itself. Thus, by mentioning the case on maps, Atlases, and books, it will be protected during different eras as a part of historical, cultural identity and saved as mans heritage. For the same reason, any change, destruction, or alteration of the names registered in historical deeds and maps is like the destruction of ancient works and is considered as an improper action. Therefore, the names of geographical features profiting from a unique historical identity, should not be utilized as political instruments in reaching a political, tribal, and racial objective, or in any clash with national interests and other's values. This paper provides a short study of the historical background of the name PERSIAN GULF so that it might cast light on realities.