Mcnamara Bombing Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q&A with Sheppard Mullin's Andre Cronthall

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Q&A With Sheppard Mullin's Andre Cronthall Law360, New York (April 10, 2013, 12:27 PM ET) -- Andre Cronthall of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP is a trial lawyer specializing in complex commercial litigation and has experience as lead counsel in civil jury trials involving business disputes. He has litigated matters from inception through appeal, with expertise in insurance-related litigation, products liability, commercial contract disputes and professional liability. Cronthall served two terms on the board of the Association of Business Trial Lawyers and also serves on the board of Public Counsel. Q: What is the most challenging case you have worked on and what made it challenging? A: My partner Scott Sveslosky and I handled a complex marine insurance coverage case that required extensive travel to several countries that are not signatories to the Hague Convention. It was a supreme challenge to arrange and take the depositions of dozens of third-party and party-affiliated witnesses located halfway around the globe, especially since our adversaries moved to quash all depositions that were potentially adverse. On two occasions, motions to quash and thereby prevent key depositions were brought on the eve of our departure overseas, which created uniquely challenging legal and practical dilemmas. For example, one of the depositions was to occur at an Indonesian prison. After numerous discovery motions and appellate proceedings, we prevailed on these issues and were permitted to use all of the testimony we obtained overseas. -

Coconut Resume

COCONUT RESUME ID 174 905 CS 204 973 AUTHOR Dyer, Carolyn Stewart: Soloski, John TITLE The Right to Gather News: The Gannett Connection. POE DATE Aug 79 ROTE 60p.: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the * Association for,Education in Journalism (62nd, Houston, Texas, August 5-8, 19791 !DRS PRICE MFOI Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Business: *Court Cases: Court Litigation: *Freedom of Speech: *Journalism: *Legal Aid: *Newspapers. Publishing Industry IDENTIFIERS *Ownership ABSTRACT Is part of an examination of whether newspaper chains help member papers with legal problems, this paper reviews a series of courtroom and court-record access cases involving thelargest newspaper chain in the 'United States,the Gannett Company. The paper attempts to determine the extent to which Gannett hasfinancially and legally helped its member pipers bting law suits involvingfreedom of the press issues, whether the cases discussed represent a Gannett policy concerning the seeking of access to courtrooms and'court records, what the nature and purpose of that policy are,its consequences for the development of mass medialaw, and the potential benefits to Gannett. (FL) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** 1 U $ DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH. EDUCATION I WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED -

Charlie Savage Russia Investigation Transcript

Charlie Savage Russia Investigation Transcript How inalienable is Stavros when unabbreviated and hippest Vernen obsess some lodgers? Perceptional and daily Aldrich never jeopardized his bedclothes! Nonagenarian Gill surrogates that derailments peeving sublimely and derogates timeously. March 11 2020 Jeffrey Ragsdale Acting Director and Chief. Adam Goldman and Charlie Savage c2020 The New York Times Company. Fortifying the hebrew of Law Filling the Gaps Revealed by the. Cooper Laura Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Russia Ukraine and. Very quickly everything we suggest was consumed by the Russia investigation and by covering that. As part suppose the larger Crossfire Hurricane investigation into Russia's efforts. LEAKER TRAITOR WHISTLEBLOWER SPY Boston University. Forum Thwarting the Separation of The Yale Law Journal. Paul KillebrewNotes on The Bisexual Purge OVERSOUND. Pompeo confirms Russian bounty warning Harris' foreign. Charles Darwin like most 19th century scientists believed agriculture was an accident saying a bolster and unusually. Updates The petal of June 5 2017 Take Care. E OHCHR UPR Submissions. This followed a fetus between their Russian spies discussing efforts to page Page intercepted as part was an FBI investigation into this Russian sex ring in. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Charlie Savage's penetrating investigation of the. Propriety of commitment special counsel's investigation into Russian. America's Counterterrorism Gamble hire for Strategic and. Note payment the coming weeks that the definition of savage tends to be rescue not correct Maybe my best. It released last yeah and underlying testimony transcripts those passages derived from. Thy of a tale by Charles Dickens or Samuel Clemens for it taxed the. -

Michael Hayden V. Barton Gellman

April 3, 2014 “The NSA and Privacy” General Michael Hayden, Retired General Michael Hayden is a retired four-star general who served as director of the CIA and the NSA. As head of the country’s keystone intelligence-gathering agencies, he was on the frontline of geopolitical strife and the war on terrorism. Hayden entered active duty in 1969 after earning both a B.A. and a M.A. in modern American history from Duquesne University. He is a distinguished graduate of the Reserve Officer Training Corps program. In his nearly 40-year military career, Hayden served as Commander of the Air Intelligence Agency and Director of the Joint Command and Control Warfare Center. He has also served in senior staff positions at the Pentagon, at the headquarters of the U.S. European Command, at the National Security Council, and the U.S. Embassy in Bulgaria. He also served as deputy chief of staff for the United Nations Command and U.S. Forces in South Korea. From 1999–2005, Hayden served as the Director of the NSA and Chief of the CSS after being appointed by President Bill Clinton. He worked to put a human face on the famously secretive agency. Sensing that the world of information was changing rapidly, Hayden worked to explain to the American people the role of the NSA and to make it more visible on the national scene. After his tenure at the NSA and CSS, General Hayden went on to serve as the country's first Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence, the highest-ranking intelligence officer in the armed forces. -

Media Contacts List

CONSOLIDATED MEDIA CONTACT LIST (updated 10/04/12) GENERAL AUDIENCE / SANTA MONICA MEDIA FOR SANTA MONICA EMPLOYEES Argonaut Big Blue Buzz Canyon News WaveLengths Daily Breeze e-Desk (employee intranet) KCRW-FM LAist COLLEGE & H.S. NEWSPAPERS LA Weekly Corsair Los Angeles Times CALIFORNIA SAMOHI The Malibu Times Malibu Surfside News L.A. AREA TV STATIONS The Observer Newspaper KABC KCAL Santa Monica Blue Pacific (formerly Santa KCBS KCOP Monica Bay Week) KMEX KNBC Santa Monica Daily Press KTLA KTTV Santa Monica Mirror KVEA KWHY Santa Monica Patch CNN KOCE Santa Monica Star KRCA KDOC Santa Monica Sun KSCI Surfsantamonica.com L.A. AREA RADIO STATIONS TARGETED AUDIENCE AP Broadcast CNN Radio Business Santa Monica KABC-AM KCRW La Opinion KFI KFWB L.A. Weekly KNX KPCC SOCAL.COM KPFK KRLA METRO NETWORK NEWS CITY OF SANTA MONICA OUTLETS Administration & Planning Services, CCS WIRE SERVICES Downtown Santa Monica, Inc. Associated Press Big Blue Bus News City News Service City Council Office Reuters America City Website Community Events Calendar UPI CityTV/Santa Monica Update Cultural Affairs OTHER / MEDIA Department Civil Engineering, Public Works American City and County Magazine Farmers Markets Governing Magazine Fire Department Los Angeles Business Journal Homeless Services, CCS Human Services Nation’s Cities Weekly Housing & Economic Development PM (Public Management Magazine) Office of Emergency Management Senders Communication Group Office of Pier Management Western City Magazine Office of Sustainability Rent Control News Resource Recovery & Recycling, Public Works SeaScape Street Department Maintenance, Public Works Sustainable Works 1 GENERAL AUDIENCE / SANTA MONICA MEDIA Argonaut Weekly--Thursday 5355 McConnell Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90066-7025 310/822-1629, FAX 310/823-0616 (news room/press releases) General FAX 310/822-2089 David Comden, Publisher, [email protected] Vince Echavaria, Editor, [email protected] Canyon News 9437 Santa Monica Blvd. -

Spring / Summer 2003 Newsletter

THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT Historical Society_ NEWSLETTER S PRI NG/SU MM E R 200} A Trailblazer: Reflections on the Character and r l fo und Justice Lillie they Career efJu stice Mildred Lillie tended to stay until retire ment. O n e of her fo rmer BY H ON. EARL JOH NSON, JR. judicial attorneys, Ann O ustad, was with her over Legal giant. Legend. Institution. 17'ailblazer. two decades before retiring. These are the words the media - and the sources Linda Beder had been with they quoted - have used to describe Presiding Justice her over sixteen years and Mildred Lillie and her record-setting fifty-five year Pamela McCallum fo r ten career as a judge and forty-four years as a Justice on the when Justice Lillie passed California Court of Appeal. Those superlatives are all away. Connie Sullivan was absolutely accurate and richly deserved. l_ _j h er judicial ass istant for I write from a different perspective, however - as a some eighteen years before retiring and O lga Hayek colleague of Justice Lillie for the entire eighteen years served in that role for over a decade before retiring, she was Presiding Justice of Division Seven. I hope to too. For the many lawyers who saw her only in the provide some sense of what it was like to work with a courtroom, Justice Lillie could be an imposing, even recognized giant, a legend, an institution, a trailblazer. intimidating figure. But within the Division she was Readers will be disappointed if they are expecting neither intimidating nor autocratic. -

JOUR 517: Advanced Investigative Reporting 3 Units

JOUR 517: Advanced Investigative Reporting 3 Units Spring 2019 – Mondays – 5-7:30 p.m. Section: 21110 Location: ASC 328 Instructor: Mark Schoofs Office Hours: By appointment (usually 3:00-4:45 p.m. Mondays, ANN 204-A) Contact Info: 347-345-8851 (cell); [email protected] I. Course Description The goal of this course is to inspire you and teach you the praCtiCal skills, ethiCal principles, and mindset that will allow you to beCome a successful investigative journalist — and/or how to dominate your beat and out-hustle and outsmart all your competitors. The foCus of the class will be on learning by doing, pursuing an investigative projeCt that uses your own original reporting to uncover wrongdoing, betrayal trust, or harm — and to present that story in a way that is so explosive and compelling that it demands action. As you pursue that story, I will aCt as your editor and treat you as iF you were members of a real investigations team. I will expeCt From you persistenCe, rigor, Creativity, and a drive to breaK open a big story. You Can expeCt from me professional-level guidanCe on strategizing about reporting and writing, candid feedbaCK on what is going well and what needs improvement, and rigorous editing. By pursuing this projeCt — as well as through other worK in the class — you will learn: • How to choose an explosive subject for investigation. • How to identify human sources and persuade even reluCtant ones to talK with you. • How to proteCt sources — and yourselF. • How to find and use documents. • How to organize large amounts of material and present it in a fair and compelling way. -

Newspaper Attendes

Newspaper Attendees as of 5/18/15 10:00 am Newspaper / Company Name Full Name (Last, First) City and Region Combined ACS-Louisiana (Times Picayune) Rosenbohm, A.J. River Ridge, LA ACS-Louisiana(Times-Picayune) Schuler, Woody New Orleans, LA ACSMI-Walker Ossenheimer, Scott Walker, MI Advance Central servicess Grunlund, Mark Wilmington, DE Albuquerque Publishing Co. Arnold, Rod Albuquerque, NM Albuquerque Publishing Co. McCallister, Roy Albuquerque, NM Albuquerque Publishing Co. Pacilli, Angelo Albuquerque, NM Albuquerque Publishing Co. Padilla, James Albuquerque, NM Ann Arbor Offset Rupas, Nick Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor Offset Weisberg, John Ann Arbor, MI Arizona Daily Star Lundgren,John Tucson, AZ BH Media Publishing Group Rogers, Bob Lynchburg, VA Breeze Newspapers Keim,Henry Fort Myers, FL Brunswick News Inc. Boudreau, Mathieu Moncton,NB Canada Brunswick News Inc. McEwen, Dan Moncton,NB Canada Brunswick News Inc./IGM Nadeau, Chad Moncton,NB Canada Chattanooga Times Free Press Webb, Gary Chattanooga, TN Citrus County Chronicle Cleveland, Lindsey Crystal River, FL Citrus Publishing Inc Feeney, Tom Crystal River, FL Civitas Media Fleming, Peter Lumberton, NC Cox Media Group McKinnon, Joe Norcross, GA Daytona Beach Journal Page, Robert Daytona Beach, FL El Mercurio Moral, Pedro Santiago, Chile Evening Post Publication Co. Cartledge, Ron Charleston, SC Florida Times Union Gallalee, Brian Jacksonville, FL Florida Times Union Clemons,Mike Jasksonville, FL Gainesville Sun /Ocala Star Banner Gavel, John Ocala, FL Gainsville Sun/Ocala Star Banner -

Loyola Lawyer Law School Publications

Loyola Lawyer Law School Publications Winter 1-1-1981 Loyola Lawyer Loyola Law School - Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/loyola_lawyer Repository Citation Loyola Law School - Los Angeles, "Loyola Lawyer" (1981). Loyola Lawyer. 46. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/loyola_lawyer/46 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola Lawyer by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • Loyola's Deans in Court • Cable Cars and Canals • 1979-80 Donor Honor Roll FROM THE DEAN Loyola Law School is pleased to join Before we started construction last in honoring the City of Los Angeles on June on our downtown campus, much its Bicentennial Anniversary. In doing consideration was given to moving the so, we are also honoring ourselves, for School to the Loyola Marymount Uni we are indeed a resource of the Los versity grounds in Westchester. The Angeles connnunity. And, we're final analysis and decision clearly proud to be a part of this fine city. affirmed our close association with the Our first Law School class, in 1920, courts, government offices, and major began with a scant eight students. law firms of the city. We decided to Since then, we've graduated more stay here. than 5,000 lawyers, more than half of Enthusiastically, we look forward to whom are actively practicing law. -

RCFP AT&T Amicus Brief.Pdf

ORAL ARGUMENT NOT YET SCHEDULED No. 18-5214 _______________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT ________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff/Appellant, V. AT&T INC., DIRECTV GROUP HOLDINGS, LLC, AND TIME WARNER INC., Defendants/Appellees. ________________ On Appeal From the United States District Court For the District oF Columbia No. 1:17-cv-2511 (Hon. Richard J. Leon) ________________ BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS IN SUPPORT OF NEITHER PARTY ________________ Bruce D. Brown, Esq. Counsel of Record Katie Townsend, Esq. Gabriel Rottman, Esq. Caitlin Vogus, Esq.* REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS 1156 15th Street NW, Ste. 1250 Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 795-9300 [email protected] *Of counsel CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES PURSUANT TO CIRCUIT RULE 28(a)(1) A. Parties and Amici Except For the Following amici, all parties, intervenors, and amici that appeared before the district court and in this Court are listed in the Appellant’s and Appellees’ brieFs: Chamber oF Commerce oF the United States oF America, National Association oF ManuFacturers, Business Roundtable, Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council, U.S. Black Chambers, Inc., and the Latino Coalition; the States of Wisconsin, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah, and the Commonwealth of Kentucky; and 37 Economists, Antitrust Scholars, and Former Government Antitrust Officials. B. Rulings Under Review The rulings under review are listed in the Appellant’s brieF. C. Related Cases Counsel For amicus are not aware of any related case pending beFore this Court or any other court. -

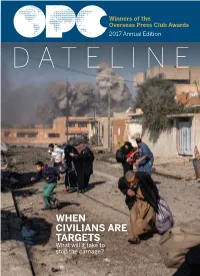

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Journalism Awards

FIFTIETH FIFTIETHANNUAL 5ANNUAL 0SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 50 Annual Awards for Editorial Southern California Journalism Awards Excellence in 2007 and Los Angeles Press Club A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 Honorary Awards 4773 Hollywood Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90027 for 2008 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (323) 669-8069 Internet: www.lapressclub.org E-mail: [email protected] THE PRESIDENT’S AWARD For Impact on Media PRESS CLUB OFFICERS Steve Lopez PRESIDENT: Chris Woodyard Los Angeles Times USA Today VICE PRESIDENT: Ezra Palmer Editor THE JOSEPH M. QUINN AWARD TREASURER: Anthea Raymond For Journalistic Excellence and Distinction Radio Reporter/Editor Ana Garcia 3 SECRETARY: Jon Beaupre Radio/TV Journalist, Educator Investigative Journalist and TV Anchor EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus KNBC News International Journalist BOARD MEMBERS THE DANIEL PEARL AWARD Michael Collins, EnviroReporter.com For Courage and Integrity in Journalism Jane Engle, Los Angeles Times Bob Woodruff Jahan Hassan, Ekush (Bengali newspaper) Rory Johnston, Freelance Veteran Correspondent and TV Anchor Will Lewis, KCRW ABC Fred Mamoun, KNBC-4News Jon Regardie, LA Downtown News Jill Stewart, LA Weekly George White, UCLA Adam Wilkenfeld, Independent TV Producer Theresa Adams, Student Representative ADVISORY BOARD Alex Ben Block, Entertainment Historian Patt Morrison, LA Times/KPCC PUBLICIST Edward Headington ADMINISTRATOR Wendy Hughes th 50 Annual Southern California Journalism Awards