Federal Firearms Prosecutions: a Primer Phillip S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

User Instructions for the Co-Ax® Primer Seater Issue 5

User Instructions for the Co-Ax® Primer Seater Issue 5 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 4.0 FILL PRIMERS IN FEED TUBE Co-Ax Primer Seater allows for fast, easy seating with a built-in primer Primers for U.S. cartridges come in two diameters — large (0.210”) and flipper and loading tray. It seats primers flat and coaxially with the small (0.175”) — and two general types — rifle and pistol. Rifle primers cartridge case for accurate alignment and penetration. have more rigid cups and a hotter flash than pistol primers. The unique design allows the operator to eliminate “slop” when working The Primer Seater comes with two sizes of the Feed Tube with a specific cartridge, translating into consistent seating, reliable (011521-011LG and 011521-011SM). To fill the Feed Tube with primers, ignition, and reduced misfires. you may use the Primer Seater tray or the Primer Tube Loader (sold separately), as described below. Case priming is a critical handloading operation because, in order for ammunition to perform efficiently, consistent powder ignition is 4.0.1 FILL PRIMERS IN BUILT-IN TRAY mandatory. Crushed, broken-tipped, or protruding primers may be dangerous or cause variations in pressure. The case must be primed 1. Empty the primers from their package into the Seater’s tray. before adding new powder, so that your gun’s propellant powder is 2. Place the Large or Small Tube into the built-in channel, as shown in contained at the bottom of the case. Fig. 1. The anvil of the primer should face the slotted side of the Tube. -

High-Speed Measurement of Firearm Primer Blast Waves

High-speed measurement of firearm primer blast waves Michael Courtney, Joshua Daviscourt, Jonathan Eng U.S. Air Force Academy, 2354 Fairchild Drive, USAF Academy, CO, 80840 [email protected] Amy Courtney Force Protection Industries, Inc., 9801 Highway 78, Ladson, SC 29456 [email protected] Abstract: This article describes a method and results for direct high-speed measurements of firearm primer blast waves employing a high-speed pressure transducer located at the muzzle to record the blast pressure wave produced by primer ignition. Key findings are: 1) Most of the lead styphnate based primer models tested show 5.2- 11.3% standard deviation in the magnitudes of their peak pressure. 2) In contrast, lead-free diazodinitrophenol (DDNP) based primers had standard deviations of the peak blast pressure of 8.2-25.0%. 3) Combined with smaller blast waves, these large variations in peak blast pressure of DDNP-based primers led to delayed ignition and failure to fire in brief field tests. Keywords: rifle primer, blast pressure, primer strength, muzzle velocity variations I. Introduction measurement method presented could be used, Over the years various surrogates have been used to together with mass sorting and measurement of quantify and compare performance of rifle primers velocity standard deviations to determine which including measuring velocity and standard deviation hypothesis is better supported in a given cartridge when the primer alone propelled a projectile from a and load. gun barrel,(1) measuring velocity, pressure, and standard deviation produced by a given primer in combination with a given powder charge and bullet,(2)(3) and measuring the size of the visible primer flash in photographs.(2)(3) This article presents a method and results for direct high-speed measurements of rifle primer blast waves employing a high-speed pressure transducer located at the Figure 1: Left: High-speed pressure transducer (on top) muzzle to record the blast pressure wave produced and signal conditioning unit. -

Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (Part 1)

NONFERROUSNONFERROUS HEATHEAT TREATING TREATING Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (part 1) Daniel H. Herring – The HERRING GROUP, Inc.; Elmhurst, Ill. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute Inc., also known as SAAMI, is an association of the nation’s leading manufacturers of rearms, ammunition and components. SAAMI is the American National Standards Institute-accredited standards Fig. 1. Firing-pin indent copper crushers developer for the commercial small arms and ammunition industry. SAAMI was for 22-caliber rimfire ammunition founded in 1926 at the request of the federal government and tasked with: creating and (courtesy of Cox Manufacturing and publishing industry standards for safety, interchangeability, reliability and quality; and Kirby & Associates) coordinating technical data to promote safe and responsible rearms use. he story of SAAMI’s rimfire firing-pin indent copper pressures and increased bullet velocities. crusher describes the reinvention of one of the most The primary advantage of rimfire ammunition is low cost, important tools in the ammunition and firearms industry typically one-fourth that of center fire. It is less expensive to T(Fig. 1). This article explains the purpose and operation manufacture a thin-walled casing with an integral-rimmed of the rimfire firing-pin indent copper crusher and how an primer than it is to seat a separate primer in the center of the unusual chain of events almost led to the disappearance of this head of the casing. simple but important technology. The most common rimfire ammunition is the 22LR (22-caliber long rif le). It is considered the most popular round Rimfire Ammunition in the world and is commonly used for target shooting, small- In order to discuss the rimfire copper crusher, we need to take a game hunting, competitive rifle shooting and, to a lesser extent, step back and first explain what rimfire ammunition is and how it works. -

The Effects of Physical Flash Hole Deviations on Factory-Grade Rifle Ammunition

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations Spring 2015 The effects of physical flash hole deviations on factory-grade rifle ammunition Nicolaas Martin Schrier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Explosives Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Schrier, Nicolaas Martin, "The effects of physical flash hole deviations on factory-grade rifle ammunition" (2015). Masters Theses. 7416. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/7416 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF PHYSICAL FLASH HOLE DEVIATIONS ON FACTORY- GRADE RIFLE AMMUNITION by NICOLAAS MARTIN SCHRIER A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EXPLOSIVES ENGINEERING 2015 Approved by Paul Worsey, Advisor Gillian Worsey Jason Baird iii ABSTRACT The objective of this research is to determine the effect of dimensional and positional changes of the primer flash hole on the performance of factory-grade rifle ammunition. The studied variables were flash hole diameter, offset from center, and orientation of the offset in the primer pocket. Cartridge performance was quantified by measuring muzzle velocity, chamber pressure, and target grouping size (precision). Five different flash hole diameters were tested for both the Remington .223 and Winchester .308 calibers: 1.4mm, 2.0mm (the Fiocchi standard), 2.4mm, 2.8mm, and 3.0mm. -

A Sharp Little Affair: the Archeology of Big Hole Battlefield

A Sharp Little Affair: The Archeology of the Big Hole Battlefield By Douglas D. Scott With Special Sections by Melissa A. Connor Dick Harmon Lester Ross REPRINTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY VOLUME 45 1994 Published by J & L Reprint Company 410 Wedgewood Drive Lincoln, Nebraska 68510 Revised for PDF publication June 2009 Acknowledgments First and foremost we wish to acknowledge and thank Hank Williams, Jr. for his interest and financial support. The National Park Service seldom has the luxury of conducting an archeological research project that is not tied to some development project or some overriding management action. Mr. William's support allowed us to pursue this investigation for the benefit of the park without being tied to a specific management requirement. His support did allow us to accomplish several management goals that otherwise would have waited their turn in the priority system. This project has had more than its fair share of those who have given their time, resources, and knowledge without thought of compensation. Specifically Irwin and Riva Lee are to be commended for their willingness to ramrod the metal detecting crew. They volunteered for the duration for which we are truly grateful. Aubrey Haines visited us during the field investigations and generously shared his vast knowledge of the Big Hole battle history with us. His willingness to loan material and respond to our questions is truly appreciated. Former Unit Manager Jock Whitworth and his entire staff provided much support and aid during the investigations. Jock and his staff allowed us to invade the park and their good-natured acceptance of our disruption to the daily schedule is acknowledged with gratitude. -

Firearms and the Decline of Violence in Europe: 1200-20101

Firearms and the Decline of Violence in Europe: 1200-20101 Carlisle E. Moody College of William and Mary College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper Number 158 January 2015 1 I would like to thank Stuart Ivinson and Jonathan Ferguson of the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds for all their help. COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER # 158 January 2015 Firearms and the Decline of Violence in Europe: 1200-2010 Abstract Personal violence, has declined substantially in Europe from 1200-2010. The conventional wisdom is that the state’s monopoly on violence is the cause of this happy result. I find some evidence that does not support this hypothesis. I suggest an alternative hypothesis that could explain at least some of the reduction in violence, namely that the invention and proliferation of compact, concealable, ready-to-use firearms caused potential assailants to recalculate the probability of a successful assault and seek alternatives to violence. I use structural change models to test this hypothesis and find breakpoints consistent with the invention of certain firearms. JEL Classification: N43, K42 Carlisle E. Moody Economics Department College of William and Mary Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 [email protected] I INTRODUCTION It is now taken for granted that crime, especially personal violence, has declined substantially in Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. ( Johnson and Monkkonen, 1996; Sharpe 1996; Malcolm 2002, Pinker 2011.) The best source of the data demonstrating this fact is Eisner (2003) who compiled a large data set on homicide rates from 1201 to 1971 from several European countries. -

The Leader in Rimfire Ammunition®

2020 CATALOG The Leader in Rimfire Ammunition® FEATURING TABLE OF CONTENTS CCI Varmint .................................................4-9 Small Game ....................................... 10-13 Target & Plinking ...............................14-17 Pest Control & Specialty ....................18-19 Primers .............................................20-21 Ballistics ...........................................22-23 BLAZER Handgun & Rimfire ...........................24-27 2 The Leader in Rimfire Ammunition® NEW PRODUCTS MAXI-MAG® & VNT™ POUR PACKS Bulk packs have never been as convenient or fun. Page 4. MAXI-MAG SEGMENTED HP There’s no escaping this. We’ve combined the power of the 22 WMR cartridge with the lethality of our exclusive Segmented Hollow Point bullet. Page 5. CLEAN-22® SUPPRESSOR Cut the noise and the fouling with this new load. Page 14. Since 1951, CCI has shaped the industry and served generations of shooters with the most advanced offerings for plinkers, hunters, competitors and reloaders. While other manufacturers are content to offer a small selection of general purpose loads, we craft ammunition customized to perform to the highest standards of specific disciplines. We carry on that tradition today, expanding our lines with new options that stretch the limits of technology even further. It’s why CCI is now the official ammunition of the USPSA Steel Challenge. Thank you for shooting CCI. cci-ammunition.com 3 VARMINT MAXI-MAG® & VNT™ POUR PACKS NEW! Got ammo? Now you do. CCI® Pour Packs hold 125 rounds of Maxi-Mag or VNT. The convenient cartons pour easily for high-volume shooting at the range or in the field. When the fun’s over, they’re easy to reclose until your next shoot. Maxi-Mag JHP ammunition provides the precision and all-around performance for a wide range of shooting and hunting, while VNT’s thin jacket and polymer tip offer accuracy and explosive expansion on impact. -

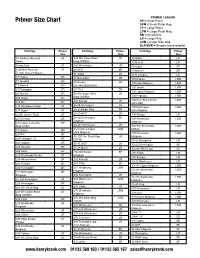

Click to View Our Primer Size Chart

PRIMER LEGEND Primer Size Chart SP = Small Pistol SPM = Small Pistol Mag LP = Large Pistol LPM = Large Pistol Mag SR = Small Rifle LR = Large Rifle LRM = Large Rifle Mag BLR/BSR = Berdan (not available) Cartridge Primer Cartridge Primer Cartridge Primer Size Size Size 10.3x60mm Rimmed LR 243 Win Super Short LR 30 Gibbs LR Swiss Mag (WSSM) 30 Herrett LR 10mm Auto LP 243 Winchester LR 30 Luger SP 11x59mm Rimmed LR 25 ACP SP 30 Mauser SP French Gras 43 Mauser 25 Gibbs LR 30 Remington LR 17 Hornet SR 25 Remington LR 300 Dakota LRM 17 Javelina SR 25 Souper LR 300 H&H Magnum LRM 17 Mach 4 SR (25-308 Winchester) 300 Jarrett LRM 17 Remington SR 25 TCU SR 300 Lapua Magnum LRM 20 Tactical SR 25 Win Super Short LR 300 Pegasus LRM 204 Ruger SR Mag (WSSM) 250 Savage LR 300 Rem Short Action LRM 218 Bee SR Ultra Mag 25-06 Remington LR 219 Donaldson Wasp LR 300 Remington LRM 219 Zipper LR 25-20 Single Shot SR Ultra Magnum 22 BR (Bench Rest) LR 25-20 WCF LR 300 Savage LR 22 CHeetah LR 25-222 Remington SR 300 Weatherby LRM Magnum 22 Cooper Centerfire SP Magnum Mag (CCM) 25-284 Winchester LR 300 Win Short Mag LRM 22 Hornet SR 25-300 Remington LRM (WSM) Ultra Magnum 22 PPC SR 300 Winchester LRM 25-300 Win Short Mag LR Magnum 22 Remington Jet SP (WSM) 30-06 Springfield LR 220 Jaybird LR 25-35 WCF LR 30-223 Remington SR 220 Russian SR 25-36 Marlin LR 30-284 Winchester LR 220 Swift LR 256 Winchester SP 303 British LR 220 Weatherby Rocket LR Magnum 303 Savage LR 220 Wilson Arrow LR 257 Roberts LR 30-30 Winchester LR 221 Fireball SR 257 STW LR 30-338 Lapua Magnum -

Download the Winchester 1866-2016 150 Years Anniversary Timeline

2010 150 YEARS OF LEGENDARY EXCELLENCE 1912 The fi rst of 1996 2003 Building on the “shorter is 1885 The Winchester Model 1885 Single Shot is 1964 many Win- The optional Ballistic better” concept, the Winchester Super In honor of the 200th 1866 With its polished brass receiver the Model The Model 1912 pump 1920 introduced. chester Factory Commemora- BOSS Optimizing Shooting Short Magnums (WSSM) are unveiled. birthday of Oliver F. 1866 “Yellow Boy” lever-action rifl e is the fi rst 1904 shotgun is introduced The Model 20, tives is a Model 1894 produced System (BOSS) is introduced, combining Winchester, Winchester gun to bear the Winchester name. The Model 1902 and becomes one of the chambered for T H A N K S F O R T H E R I D E for the Wyoming Diamond a barrel tuner and ported muzzle break o¥ ers a special Model 1895 single-shot .22 rimfi re world’s most popular the.410 shotshell 2008 The Model 70 rifl e Jubilee. It remains among the that allows the shooter to fi ne tune their 1894 rifl e and limited MAY 22,1866 1886 The Model 1886 lever-action rifl e is rifl e is introduced and and respected designs is introduced and returns, equipped with the 1866 Winchester introduces its fi rst commercial rarest of the all Winchester rifl e with just a twist of the wrist. edition collectible The iconic Winchester brand celebrates 150 years of introduced to handle the large cartridges becomes famous as of all time. included in the latest three-lever M.O.A. -

Modern Use of Percussion Revolvers and Cartridge Conversions

Page 1 JANUARY 2021 Columns & News The GunNews is the official monthly publication of the Washington 3 Legislation & Politics–Joe Waldron Arms Collectors, an NRA-affiliated organization, P.O. Box 400, Sumner, 6 Straight From the Holster–JT Hilsendeger WA 98390. Subscription is by membership only and $15 per year 23 Short Rounds of membership dues goes for subscription to the magazine. 24 Interview with a Gunsmith–Tom Burke Features Managing Editor–Philip Shave 8 American Percussion Revolvers–Dick Send editorial correspondence, Wanted Dead or Farnsworth Alive ads, or commercial advertising inquiries to: 16 Shooting Those C&R's–Ray Heltsley [email protected] 7625 78th Loop NW, Olympia, WA 98502 For Collectors (360) 866-8478 26 Wanted: Dead or Alive Assistant Editor–Bill Burris 32 Show Calendar Art Director/Covers–Bill Hunt Copy Editors–Bob Brittle, Bill Burris, Forbes Cover–Some of Freeburg, Woody Mathews Member Resources the loading tools 5 Board Minutes that are useful 31 Renewal forms in loading for CONTACT THE BUSINESS OFFICE FOR: obsolete car- tridges. Ray n MISSING GunNews & DELIVERY PROBLEMS Heltley photo. n TABLE RESERVATIONS n CHANGE OF ADDRESS n TRAINING n CLUB INFORMATION, MEMBERSHIP Club Officers President — Bill Burris (425) 255-8410 (425) 255-8410 voice Vice President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 Office Phone Hours: 9a.m.–5p.m., M–TH Secretary — Forbes Freeburg (425) 255-8410 closed holidays Treasurer — Holly Henson (425) 255-8410 Immediate Past President — Boyd Kneeland (425) 643-9288 There is no physical office–staff may be reached by phone or email. Club Board of Directors Scott Bramhall (425)255-8410 John Hubbard (425) 255-8410 SEND OFFICE CORRESPONDENCE TO: Bill Palmer (425) 255-8410 Richard Ripley (206) 271-0670 P.O. -

Federal Firearms Primer

PRIMER FIREARMS June 2016 Prepared by the Office of General Counsel, U.S. Sentencing Commission Disclaimer: This document provided by the Commission’s Legal Staff is offered to assist in understanding and applying the sentencing guidelines. The information in this document does not necessarily represent the official position of the Commission, and it should not be considered definitive or comprehensive. The information in this document is not binding upon the Commission, courts, or the parties in any case. Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 32.1 (2007), some cases cited in this document are unpublished. Practitioners should be advised that citation of such cases under Rule 32.1 requires that such opinions be issued on or after January 1, 2007, and that they either be “available in a publicly accessible electronic database” or provided in hard copy by the party offering them for citation. Primer on Firearms TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. RELEVANT STATUTES ........................................................................................................................................ 1 A. SUBSTANTIVE OFFENSES ................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Firearms Transfer Offenses: 18 U.S.C. §§ 922(a)(6) (“straw purchase”), 922(d) (“prohibited person”), and 924(a)(1)(A) (“false statement in a record”) -

Curios Or Relics List — January 1972 Through April 2018 Dear Collector

Curios or Relics List — January 1972 through April 2018 Dear Collector, The Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division (FATD) is pleased to provide you with a complete list of firearms curios or relics classifications from the previous editions of the Firearms Curios or Relics (C&R) List, ATF P 5300.11, combined with those made by FATD through April 2018. Further, we hope that this electronic edition of the Firearms Curios or Relics List, ATF P 5300.11, proves useful for providing an overview of regulations applicable to licensed collectors and ammunition classified as curios or relics. Please note that ATF is no longer publishing a hard copy of the C&R List. Table of Contents Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ............................................................................................1 Section III — Firearms removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................23 Section IIIA —Firearms manufactured in or before 1898, removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as antique firearms not subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ..............................................................................65 Section IV — NFA firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 26 U.S.C. Chapter 53, the National Firearms Act, and 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................83 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C.