The Queer Art of Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deliver Us to Cinema: the Prince of Egypt and Cinematic Depictions of Religious Texts

Deliver Us to Cinema: The Prince of Egypt and Cinematic Depictions of Religious Texts Kadii Lott Introduction There is a pervasive Hollywood culture of appropriating and commodifying biblical concepts and imagery into films that do not explicitly address the Abrahamic belief systems that consider the Old and New Testaments as sacred texts. Many such films received mixed reviews. Christian and Jewish groups have heavily criticised particular adaptations of scriptural stories, including Life of Brian,1 The Last Temptation of Christ,2 The Passion of Christ,3 and Noah,4 for their blasphemous or ill-intentioned treatment of biblical figures. Despite the protectiveness of religious people Kadii Lott received First Class Honours in Studies in Religion at the University of Sydney in 2020. 1 The 1979 religious satire reimagined the fictional life of a man named Brian who gets mistaken for Jesus. The film was considered blasphemous by some Christians who protested against the release and the film was banned in many countries upon its release, including in Ireland and Norway. See Ben Dowell, ‘BBC to dramatise unholy row over Monty Python’s Life of Brian’, The Guardian (21 June 2011), https://www.theguardian.com/media/ 2011/jun/21/bbc-monty-python-life-of-brian. Accessed 13 July 2020. 2 Scorsese’s depicted Jesus Christ dealing with worldly temptations like everyone else. This caused outrage amongst some Christian groups, even leading to an incident in Paris where a theatre showing the film was set on fire. See Steven Greenhouse, ‘Police Suspect Arson In Fire at Paris Theater’, The New York Times (25 October 1988), p. -

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

Painting Identity: the Disconnect Between Theories and Practices of Art by the LGBTQ Community

Painting Identity: The Disconnect Between Theories and Practices Of Art by the LGBTQ Community Meg Long Advisor: Sarah Willie-LeBreton May 7,2012 2 Table of Contents Acl(nowledgements ........................................................................... 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................. 4 2. Perspectives on Racial and Sexual Identity in Modem and Contemporary Art .......................................................................................... 10 3. Influence of Self Identity for Contemporary Artists .......................................... 33 4. Discourse Analysis: Art and Sexual Identity ......................................... 55 5. Conclusion .................................................................................76 Worl(s Cited .............................................................................. 84 Appendix A ............................................................................... 86 Appendix B ............................................................................... 87 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, thank you to my father for his endless support throughout this process; as always in life, I would be lost without him. Likewise, thank you to my mother for her energy and encouragement. I also cannot be appreciative enough of my advisor, Professor Sarah Willie-LeBreton for helping me in more ways than I can enumerate, even when my process was dubious at best. Thank you to the participants who shared their stories -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. _ _____ · " VOLUME 78. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 1911. NUMBER 39. s with "Who are ehe asked, "and d. park. Fruit Eating Birds. lima seemed always to have something Mies Greye flue eyea biased 70α," Pau- what are here?* ^lbkbt AMONG THE FARMERS. on her mind. For a time ehe was anger. "I do not forbid yoα to, you doing Licensed Auctioneer, a and I her admirers as bat line, bot I bope you will not Paul "I'm pin peddler, stopped THJE GROWER SUPFKBS, BUT HS 8H0UM Bought by before, "OUTH PARIS, MAIN·. "vim THE PLOW." Is a man. here for Picked For like seeks like, and the young men, The Gate In Graham's father detestable THE ΉΝ overnight." THEM. Out MolerMe. CONSIDER HIS GAINS FROM must be Tenu» finding her preoccupied and unenter- Wbeu I tell yoa that once upon a time "Is that all? Τ thought you on practical agricultural topic him be was a β robber." Correspondence drew away to more I was engaged to marry L. BUCK, la solicited. Address all communication· la talnlng, gradually "Grape Grower," Keuka Lake, N. T., was a lad in "1 a robber would be more tended (or this department to Bikii D Each Other animated companions. I, too, with the The widower, and Paul little PEDDLER suppose U ^ Hammond, Editor Oxford Dem write·: "What redreae there Hedge is a attractive to than a tin Surgeon Dentist, Agricultural secret on my mind, was and dresses then. Walter Graham you peddler." ocrat, Parle, Me. the ravage· of bird· on fruit? My choic- moody MAIN'S. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

A Father's Love

A FATHER’S LOVE The documentary movie The March of the Penguins follows the Emperor Penguins of Antarctica on their incredible journey through ice and snow to mating grounds up to 70 miles inland. Narrated by Morgan Freeman, this beautiful film captures the drama of these three-foot-high birds in the most inhospitable of environments. Once the penguins have made the trek to their mating grounds and the females have produced their single eggs, a remarkable exchange occurs. Through an intricate dance, each mother swaps her egg into the father's care. At this point the father becomes responsible for the egg and must keep it warm. As this part of the story unfolds, the camera shows remarkable shots of the penguin fathers securing the eggs on top of their feet and sheltering them against the cold, which will drop to as low as 80 degrees below zero. Freeman narrates: Now begins one of nature's most incredible and endearing role reversals. It is the penguin male who will tend the couple's single egg. While the mother feeds and gathers food to bring back for the newborn, it is the father who will shield the egg from the violent winds and cold. He will make a nest for the egg atop his own claws, keeping it safe and warm beneath a flap of skin on his belly. And he will do this for more than two months… As the winter progresses, the father will be severely tested. By the time their vigil on top of the egg is over, the penguin fathers will have gone without food of any kind for 125 days, and they will have endured one the most violent and deadly winters on earth, all for the chick. -

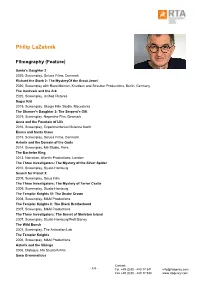

Philip Lazebnik

Philip LaZebnik Filmography (Feature) Santa’s Daughter 2 2020, Screenplay, Deluca Films, Denmark Richard the Stork 2: The MysteryOf the Great Jewel 2020, Screenplay with Reza Memari, Knudsen and Streuber Productions, Berlin, Germany The Aardvark and the Ark 2020, Screenplay, Unified Pictures Sugar Kid 2019, Screenplay, Skopje Film Studio, Macedonia The Shamer’s Daughter 2: The Serpent’s Gift 2019, Screenplay, Nepenthe Film, Denmark Anna and the Fountain of Life 2016, Screenplay, Experimentarium/Science North Emma and Santa Claus 2015, Screenplay, Deluca Films, Denmark Asterix and the Domain of the Gods 2014, Screenplay, M6 Studio, Paris The Bachelor King 2013, Narration, Atlantic Productions, London The Three Investigators: The Mystery of the Silver Spider 2010, Screenplay, Studio Hamburg Search for Planet X 2009, Screenplay, Sirius Film The Three Investigators: The Mystery of Terror Castle 2009, Screenplay, Studio Hamburg The Templar Knights III: The Snake Crown 2008, Screenplay, M&M Productions The Templar Knights II: The Black Brotherhood 2007, Screenplay, M&M Productions The Three Investigators: The Secret of Skeleton Island 2007, Screenplay, Studio Hamburg/Walt Disney The Wild Bunch 2007, Screenplay, The Animation Lab The Templar Knights 2006, Screenplay, M&M Productions Asterix and the Vikings 2006, Dialogue, M6 Studio/A Film Saxo Grammaticus Contact: - 1/4 - Tel. +49 (0)30 - 440 17 341 [email protected] Fax +49 (0)30 - 440 17 930 www.rtagency.com 2006, Film/Story Consultant, Radar Film The Ugly Duckling 2006, Film/Story Consultant, -

Nine Night at the Trafalgar Studios

7 September 2018 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S PRODUCTION OF NINE NIGHT AT THE TRAFALGAR STUDIOS NINE NIGHT by Natasha Gordon Trafalgar Studios 1 December 2018 – 9 February 2019, Press night 6 December The National Theatre have today announced the full cast for Nine Night, Natasha Gordon’s critically acclaimed play which will transfer from the National Theatre to the Trafalgar Studios on 1 December 2018 (press night 6 December) in a co-production with Trafalgar Theatre Productions. Natasha Gordon will take the role of Lorraine in her debut play, for which she has recently been nominated for the Best Writer Award in The Stage newspaper’s ‘Debut Awards’. She is joined by Oliver Alvin-Wilson (Robert), Michelle Greenidge (Trudy), also nominated in the Stage Awards for Best West End Debut, Hattie Ladbury (Sophie), Rebekah Murrell (Anita) and Cecilia Noble (Aunt Maggie) who return to their celebrated NT roles, and Karl Collins (Uncle Vince) who completes the West End cast. Directed by Roy Alexander Weise (The Mountaintop), Nine Night is a touching and exuberantly funny exploration of the rituals of family. Gloria is gravely sick. When her time comes, the celebration begins; the traditional Jamaican Nine Night Wake. But for Gloria’s children and grandchildren, marking her death with a party that lasts over a week is a test. Nine rum-fuelled nights of music, food, storytelling and laughter – and an endless parade of mourners. The production is designed by Rajha Shakiry, with lighting design by Paule Constable, sound design by George Dennis, movement direction by Shelley Maxwell, company voice work and dialect coaching by Hazel Holder, and the Resident Director is Jade Lewis. -

Epic Antarctica (Ng Endurance)

EPIC ANTARCTICA (NG ENDURANCE) Active, immersive expedition travel Exploring Antarctica in an authentic expedition style, aboard an authentic expedition ship is an incomparable experience, and your guarantee of an in-depth encounter with all its wonders. Lindblad Expedition’s pioneering polar heritage and 50 years of experience navigating polar geographies is your assurance of safe passage in one of the wildest sectors of the planet. Have up-close, personal penguin encounters Travel with virtually any company to Antarctica, and you will see penguins. They are the citizens of the white continent, present in astounding numbers, and endlessly fascinating. Travel with Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic, however, and you’ll travel equipped for up-close, personal encounters—with a fleet of Zodiacs and kayaks to enable you to get closer. And a team of engaging experts that waiting around for returning parties. You’ll have a choice of enable you to spend more time enjoying penguin society, and activities each day, and the option to join the naturalist whose understand more of the adaptations that enable these interests mirror yours. Choice also includes opting to enjoy the remarkable animals to survive their environment. Take view from the bridge, the all-glass observation lounge, the advantage of all the superb photo ops You’ll have a National library or the chart room. To visit the fitness center with its Geographic photographer as your traveling companion, to panoramic windows, or ease into the sauna or a massage in the inspire you and provide tips in the field. And the services of a wellness center. -

The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism

“Glory of Yet Another Kind”: The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism, 1867-1924 GVGK Tang HIST4997: Honors Thesis Seminar Spring 2016 1 “What could you boast about except that you stifled my words, drowned out my voice . But I may enjoy the glory of yet another kind. I raised my voice in free and open protest against a thousand years of injustice.” —Karl Heinrich Ulrichs after being shouted down for protesting anti-sodomy laws in Munich, 18671 Queer* history evokes the familiar American narrative of the Stonewall Uprising and gay liberation. Most people know that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people rose up, like other oppressed minorities in the sixties, with a never-before-seen outpouring of social activism, marches, and protests. Popular historical discourse has led the American public to believe that, before this point, queers were isolated, fractured, and impotent – relegated to the shadows. The postwar era typically is conceived of as the critical turning point during which queerness emerged in public dialogue. This account of queer history depends on a social category only recently invented and invested with political significance. However, Stonewall was not queer history’s first political milestone. Indeed, the modern LGBT movement is just the latest in a series of campaign periods that have spanned a century and a half. Queer activism dawned with a new lineage of sexual identifiers and an era of sexological exploration in the mid-nineteenth century. German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was first to devise a politicized queer identity founded upon sexological theorization.2 He brought this protest into the public sphere the day he outed himself to the five hundred-member Association 1 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, The Riddle of "Man-Manly" Love, trans. -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out