Name: Joe Beckett Career Record: Boxer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hand-Book to Boxing;

FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION NOTES: This document is an attempt at a faithful transcription of the original document. Special effort has been made to ensure that original spelling (this includes what may be typographical errors such as the 1776 reference on pp29 which should, apparently, be 1766 or pp39 where June 10 appears twice and should, at a guess, be July 10 in the second appearance, and, my favorite, July 40, on pp46), line-breaks, and vocabulary are left intact, and when possible, similar fonts have been used. However, it contains original formatting and image scans. All rights are reserved except those specifically granted herein. Of particular note in this reproduction is the unusual (by today’s standards) selection of page and font size. The page size is, in the original 6” x 10” with a font approximately 9 point for large portions of the book. Reproducing it in 6x9 with smaller top and bottom margins with hand tweaked font, paragraph, and line spacings, I have tried to recaptured the original personality of the book. However, this can make it difficult to read. Be assured that this was maintained in order to keep the “flavor” of the original text but it can be taxing on the eyes. LICENSE: You may distribute this document in whole, provided that you distribute the entire document including this disclaimer, attributions, transcriber forewords, etc., and also provided that you charge no money for the work excepting a nominal fee to cover the costs of the media on or in which it is distributed. You may not distribute this document in any for-pay or price- metered medium without permission. -

Yfj. HAS TWO GAMES VERY FAST and CHASES WILLARD SEVENTH CAVALET on CREDIT STRING CARRIES a PUNCH for TITLE MATCH to MEET TRAIN PASO Will a M P Team, by TORK, Dec

S-'- 1 LIFE 10 iL rA5U tltKALU UK I J, KHUKJbA IUIN ana UUIUOOK TRYING TO GET TUB GAME. CODY BASEBALL Kin M'PflRTIflP indoor sports OF THE GANG. BY "TAD FULTD SBEST FOOTBALL i ftoAiT" OF BIG BOXERS ARRANGED FOR TEAM TO VISIT LIKES WORK OF TCE of , AT MIGHT ii i TODAY, GHHISTIIUIS DHf GITYSATURDAYBENNY LEONARD wmm ' smoke 'l .iWM Her sota nK "Will Clash Cantonment Nine Will En - Veteran Referee Declares! Would Undoubtedly Defeat Cavalry Teams AtK Pad - '". gage Fort Bliss in Final j That Lightweight King fi! ?yT"C"GUT- All Contenders for the at Stadium in Afternoon Two Games of Series. Is the Best Ever. I Heavyweight Title. of Holiday. i Yfj. HAS TWO GAMES VERY FAST AND CHASES WILLARD SEVENTH CAVALET ON CREDIT STRING CARRIES A PUNCH FOR TITLE MATCH TO MEET TRAIN PASO will A M P team, By TORK, Dec. .Fred Ful football enthusiasts OODTS crack baseball JACK VBIOCK. on I recently trimmed the Ft. YORK, Dec. 20. Mc 1ST ton has shown himself to be not be left oat In the cold Kid heavyweight In E" spite th" Bliss nine In two decisive battles Partland, recognized in the the best the Christmas dar in of country, barring champion, and Bliss-Cod- y return on the cantonment diamond, will in-- v N"east as one of the best of pres tbe calling off of the if V.' 11 any of again game, arrange 1 .ae HI Paso Saturday and Sunday ent day referees, has advanced a new lard has intention as a contest has been Ie fon tl i n g his title the Minneaotan cavalry regi- s f t en oon, and a combined front of argument to substantiate the con between the Serenth , the logical opponent. -

Myrrh NPR I129 This Newsletter Is Dedicated to the Nucry of Jim

International Boxing Research Organization Myrrh NPR i129 This newsletter is dedicated to the nucry of Jim Jacobs, who was not only a personal friend, but a friend to all boxing his- torians. Goodbye, Jim, I'll miss you. From: Tim Leone As the walrus said, "The time has come to talk of many things". This publication marks the 6th IBRO newsletter which has been printed since John Grasso's departure. I would like to go on record by saying that I have enjoyed every minute. The correspondence and phone conversations I have with various members have been satisfing beyond words. However, as many of you know, the entire financial responsibility has been paid in total by yours truly. The funds which are on deposit from previous membership cues have never been forwarded. Only four have sent any money to cover membership dues. To date, I have spent over $6,000.00 on postage, printing, & envelopes. There have also been a quantity of issues sent to prospective new members, various professional groups, and some newspapers.I have not requested, nor am I asking or expecting any re-embursement. The pleasure has been mine. However; the members have now received all the issues that their dues (sent almost two years ago) paid for. I feel the time is prudent to request new membership dues to off-set future expenses. After speaking with various members, and taking into consideration the post office increase April 1, 1988, a sum of $20.00, although low to the point of barely breaking even, should be asked for. -

HLETIC GAME! CARPENTIER's [This Sicene Will Be Enacted Just Before Bell for Firist Round J!BRONX BOYS RETAIN IN

f Q 4 THE: NEW YORK HERALE), SUNDAY, JUNE 12, 1921. O ' AT THIv CAM1>S OK rHE BICr BOXERS - ATHLETIC GAME! CARPENTIER'S [This Sicene Will Be Enacted Just Before Bell for Firist Round j!BRONX BOYS RETAIN IN. Y.A.C.Ath/efes in VIGORj P.S.A.L. TEAM TITLE\ Junior Championshiv TOBGTESTEDJULY2 <kr I Continued First i r .... I I..^im/iAccfnl Ii» HftfnnH ll iuwti'v ff from Page. New Junior Metropolitan Ability of Challenger to Games at the field carrying: before It a cloud of j Sur-j Championship of A. A. U. » rive Jolts Will Be dust that lasted all during the contests, Champions Heavy Brooklyn Field. This wind slowed up most of the races. 100 > «Rn IIASll-UrKini Prin<-rtnn 11.,I I Definitely Settled. vrrsily. surely handicapped their efforts. 220 1 V CI> Ht'N.Yonhass, r.lrnior A. / >$ Pupils of Public School No. 37 of Th< Y'AICD Itl N.Stesrnson, Prince Princeton took things right In hand I'nlt entity. Bronx successfully defended ihelr tearr by getting both first and second in the 880 Y'AICD itl N.Parker, St. < liristop DEMPSEY SUKE TO LAND the annual field ant 100 A. « titular honors In yards dash with McKIm and T-leber- Mil.I. Itl N .flrennu, New York A. C. track champlonelps of the P. S. A. L. ai man, who outclassed their competitors. THK/.r. Mil i: Itl V.Kick. Princeton. The I .'U Y Athletic Field Th< tlrne of 10 2-5 seconds into the wind Altl> III ItlH.KS.Zunter, N. -

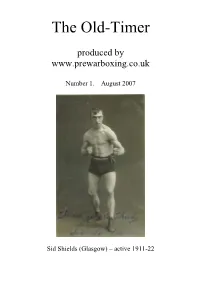

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 11 22 May , 2009

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 4- No 11 22 May , 2009 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website Harry Mizler Part 6 and the final installment Just before he was matched with AI Roth of New York Mizler became friendly with Betty Greenfield an attractive young woman who was to become his wife two years later. Betty met Roth at a dance and asked him during the course of conversation what he did for a living. The exchanges went something like this: Al (swelling out his chest and trying to look nonchalant "I'm a professional boxer." Betty (surprised): What a coincidence! My boy friend is a fighter—his name is Harry Mizler." Al: "Oh, that guy. I may be meeting him in the ring soon which will be tough luck for him. I’ll slaughter him." TIPPED FOR TITLE That story may carry more than one moral, but it may also have spurred Mizler to be at the peak or his form and outpoint the American by an overwhelming margin over ten rounds. Certainly Harry looked brilliant and besides being awarded a "Boxing News" Certificate of Merit was very strongly tipped to regain the British lightweight title. For the contest, made at ten stone. John Harding paid Mizler £250 and Roth £150. And to this day looks back at the promotion and considers it the best bargain he over made. -

Kearnsstartles Worldofsports

WHEN THEY HAVE ABOLISHED FREAK PITCHING WE KNOW SOME LADS WHO WONT HAVE ANYTHING CTTTHE BALL BUT THE COVER arss-is-ai The Times' Complete,Sport Page ijrB.-asast <C«pr1tH 1»1». kr Iwt__ LOOKING 'EM OVER Indoor Sports (.me*. By TAD WALTERCAMPDONE 1 BY I IKMo LETT S£E - *'U- <r^£ (VSMON TV*. pOAiCH (?0\NC- LOUIS A. DOUGHER E0OIE V*. VN'Nt ASFOOTBALL HEAD OAKe TVtc CousTJA|U SHA*£*- WIU- TH.. WOfW ttpi*JOi~£0 Brink Thorn# Hoado New Mike O'Dowd, world's middleweight champion, through his man¬ Cork 5CK£VJ - 7 to ager, Paddy MaUins, threatens to ruin the game of those who would Winner kDlPlFofi^ vitory Body arraage a championship contest between Georges Carpentier, European by Knockout, AAiWON^y" Yale Conditions. tttieholder, and Jack Dempsey, the Salt Lake City slugger who took Thinks Other Way. the cmwu from the fat head of one Jess Willard, at Toledo, on July NEW HAVEN. Com.. Dm. IB- 1919. O'Dowd would battle as a test 4» Carpentier for the Frenchman. Noted trirM of Tale'a footkaE fcta> "O'Dowd is the to Knocked down in the first logical American fight Carpentier," says Mul- round of a scheduled ten-round tory ptmi out W actIt# lias. "Dempsey is not the man to go against the Frenchman. That bout wfth Mickev Rodtrers be¬ ii ttw la grMlrw MtlrtttN M th* wouldn't be a fight; it would be a murder. Carpentier made a poor fore the Keystone Club in Pitts- Terelty wkti tlM ratcuUn .bowing a few months ago against Dick Smith. -

Fight Record Harry Reeve

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Harry Reeve (Plaistow) Active: 1910-1934 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 167 contests (won: 90 lost: 53 drew: 22 other: 2) Fight Record 1910 Sep 22 Spike Wallis WKO1(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 01/10/1910 page 752 (9st 4lbs novice competition 1st series) Sep 24 Harry Selleg (Peckham) W(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 01/10/1910 page 752 (9st 4lbs novice competition 2nd series) Oct 1 Pte. Saunders (Royal Irish Rifles) W(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 08/10/1910 page 774 (9st 4lbs competition 3rd series) Oct 13 Harry French (Spitalfields) WRSF1(3) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 22/10/1910 page 817 (9st 4lbs novice competition semi-final) Oct 15 Young Riley (Haggerston) LRSF6(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 22/10/1910 pages 817 and 821 (9st 4lbs novice competition final) Nov Dick Cartwright (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Record published in Boxing News in the 1960s Nov Bill Bennett (Dublin) WRSF2 The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Record published in Boxing News in the 1960s 1911 Tom Leary (Woolwich) LPTS Source: Brian Strickland (Boxing Historian) Fred Davidson DRAW Source: Brian Strickland (Boxing Historian) Jan 14 Mark Barrett (Lambeth) WRTD4(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 21/01/1911 page 303 Mar 13 Dick Cartwright (Blackfriars) WPTS(6) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 18/03/1911 pages 498 and 499 May -

Fight Record Ted Kid Lewis (St George's)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Ted Kid Lewis (St George's) Active: 1909-1929 Weight classes fought in: bantam to light-heavy Recorded fights: 257 contests (won: 147 lost: 30 drew: 12 other: 68) Born: 28th October 1893 Died: 20th October 1970 Manager: Self Trainer: Alec Goodman Mini Bio Ted Kid Lewis was, in my view, the finest pound for pound boxer this country has produced. He started out as a flyweight, aged 14, boxing at the old Judaean Club near Cable Street, St George's, and boxed the world over against the very best men at virtually every weight. He also promoted regularly at Premierland in Whitechapel and was a household name throught Great Britain. He won the British featherweight title aged 17 and departed almost immediately to Australia, from where he journeyed to the United States, where he really made his name. Fight Record 1909 Aug 29 Kid Da Costa (Mile End) LPTS(6) Judaeans AC, St George's Source: Sporting Life Referee: Young Joseph Attendance: 1000 Sep 19 Young Lipton (Stepney) WPTS(6) Judaeans AC, St George's Source: Boxing 25/09/1909 page 61 Oct 9 Alf Cohen WPTS Judaeans AC, St George's Source: Boxing 16/10/1909 page 139 Oct 30 George Thomas (Clerkenwell) LRSF1(3) Sadler's Wells, Clerkenwell Source: Boxing 06/11/1909 page 216 (8st novice competition 2nd series) Nov 27 Jack Marks (Aldgate) WPTS(6) Surrey Music Hall, Southwark Source: Boxing 04/12/1909 page 336 Dec 6 Dick Hart (Mile End) DRAW(6) Judaeans -

Fight Record Joe Beckett (Southampton)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Joe Beckett (Southampton) Active: 1912-1923 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 59 contests (won: 47 lost: 11 drew: 1) Fight Record 1912 Jan 29 Seaman McMullen DRAW(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 03/02/1912 page 338 Feb 3 Albert Croucher (Southampton) WPTS(6) Palace Theatre, Southampton Source: Boxing 10/02/1912 page 370 Promoter: Will Murray Feb 15 L/Cpl. Dyer (Gloucester Regt) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight competition 1st series) Referee: E Zerega Feb 15 Pte. Bancroft (RAMC) WPTS(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight competition 2nd series) Referee: E Zerega Feb 19 Young Pughey (Brighton) LPTS4(3) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing (Middleweight novice competition 3rd series) Referee: JH Douglas extra round Mar 4 Seaman Nicholls (Southampton) WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 09/03/1912 page 470 Apr 22 Pte. Ponsford (RMLI) WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 27/04/1912 page 638 Apr 29 Fred Ball (Mile End) WRSF3(6) Dome, Brighton Source: Boxing 11/05/1912 page 44 Jun 10 Jim Hearne (Marylebone) WPTS(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 15/06/1912 page 157 Referee: G T Dunning Sep 30 Sid Broadbent WPTS(6) Pelican Hall, Southampton Source: Boxing 05/10/1912 page 546 Oct 14 Albert Lawner (Battersea) WKO4(6) National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 19/10/1912 pages 593 and 594 Nov 18 Packey Mahoney (Ireland) LKO2 National Sporting Club, Covent Garden Source: Boxing 23/11/1912 page 89 Mahoney boxed for the British Heavyweight Title 1913. -

Town of Dedham Annual Report 2009/2010

Town of Dedham Annual Report 2009/2010 WHERE TO CALL: EMERGENCY: POLICE Emergency Calls 911 Other Calls: 751-9300 FIRE Emergency Calls 911 Other Calls: 751-9400 FOR INFORMATION ON: Administration Town Administrator 751-9100 Assessments Assessors 751-9130 Bills & Accounts Finance Department 751-9150 Birth Certificates Town Clerk 751-9200 Building Permits Building Commissioner 751-9180 Cemetery Superintendent of Cemeteries 326-1177 Civil Defense Director 751-9300 Code Enforcement Enforcement/Compliance 751-9186 Counseling, etc. Youth Commission 326-3120 Council on Aging Elder Services 326-1650 Death Certificates Town Clerk 751-9200 Dog Licenses Town Clerk 751-9200 Dogs, Lost, Found, Complaints Canine Controller 751-9106 Elder Services Council on Aging 326-1650 Elections Town Clerk 751-9200 Entertainment Licenses Selectmen 751-9100 Environment Conservation Commission 751-9210 Finance Committee Finance 751-9140 Finance Director Finance 751-9150 Fire Permits Fire Department 751-9400 Fuel Oil Shortage Fire Department 751-9400 Gas Permits Gas Inspector 751-9183 Health Board of Health 751-9220 Housing Inspections Housing Inspector 751-9220 Information Services Technology 751-9145 Library Main Library 751-9280 Endicott Branch 326-5339 Lights (street lights out) Police Department 751-9300 Marriage Licenses Town Clerk 751-9200 Planning Board Planning Director 751-9240 Plumbing Permits Plumbing Inspector 751-9183 Recreation Recreation Department 751-9250 Retirement Retirement Board 326-7693 Schools Superintendent of Schools 326-5622 No School 326-9818 -

MARY STALLINGS ANGELICA SANCHEZ PAUL Mccandless

SEPTEMBER 2016—ISSUE 173 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM STEVE COLEMAN elemental MARY ANGELICA PAUL LAURIE STALLINGS SANCHEZ McCANDLESS FRINK Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East SEPTEMBER 2016—ISSUE 173 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Mary Stallings 6 by suzanne lorge [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Angelica Sanchez 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Steve Coleman 8 by russ musto Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Paul McCandless by john pietaro Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Laurie Frink 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : WhyPlayJazz by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] In Memoriam by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD Reviews 14 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Miscellany 33 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 34 Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Tyran Grillo, Matthew Kassel, Eric Wendell, Scott Yanow 60 is the new 40, which is the new black, which is the...you get the idea.