Wind That Shakes the Seas and Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morning Phase", Il Nuovo Album Di BECK

MARTEDì 25 FEBBRAIO 2014 È disponibile da oggi nei negozi tradizionali e negli store digitali "Morning phase", il nuovo album di BECK. L'album, a poche ore dalla pubblicazione, è già presente nella TopTen di iTunes dei principali paesi Beck, è uscito oggi il nuovo album del mondo a cominciare dagli Stati Uniti e il Canada, passando per la "Morning phase" Gran Bretagna e i paesi del nord Europa fino ad arrivare all'Italia. Il disco già in TopTen su iTunes "Morning phase" è il dodicesimo lavoro di studio del cantautore americano ed è il primo disco contenente materiale inedito dall'uscita di "Modern Guilt" del 2008. ANDREA LECCARDI In scaletta 12 brani inediti: "Morning", "Heart Is A Drum", "Say Goodbye", "Waking Light", "Unforgiven", "Wave", "Don't Let It Go", "Blackbird Chain", "Evil Things", "Blue Moon", "Turn Away", "Country Down". Intervistato a proposito del nuovo album dal magazine inglese Q, Beck ha chiarito nel dettaglio quali sono state le ispirazioni e le fonti che hanno dato vita ai brani del nuovo album: "Sono tornato alla musica della [email protected] mia giovinezza e delle mie radici: parlo di Neil Young, Gram Parsons e SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Crosby, Stills, & Nash. Ricordo sempre il suono di quei dischi e di quelle registrazioni, erano parte di una cultura mentre crescevo. Fanno parte del mio imprinting di crescita, che mi piaccia o meno. Forse rifiutavo questa musica quando ho cominciato a suonare, perché cercavo di trovare la mia identità. Ma sia io sia tutti quelli che hanno suonato su questo disco, siamo cresciuti tutti in California e quindi questo tipo di musica è inevitabilmente parte del nostro DNA". -

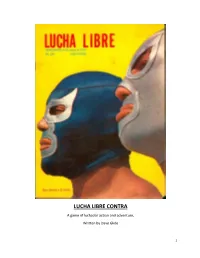

Lucha Libre Contra

LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA A game of luchador action and adventure, Written by Dave Glide 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Agendas & Principles; GM Moves; World & Adventures CHARACTER CREATION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Concept; Stats; Roles; Moves; History; Fatigue; Glory; Experience & Reputation Levels CHARACTER ROLES ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Tecnico; Rudo; Monstruo; High-Flyer; Extrema; Exotico GENERICO MOVES ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 Rookie; Journeyman; Professional; Champion; Legend ADVANCED CHARACTER OPTIONS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Starting Above “Rookie;” Cross-Role Moves; Alternative Characters; Character Creation Example TAKING ACTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 29 Combat & Non-Combat Moves LUCHA COMBAT and CULTURE NOTES ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Match Rules; Lucha Terminology; Optional Rules ENEMIES OF THE LUCHADORES …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 48 Monster Stats; Henchman; Mythology and Death Traps SAMPLE VILLAINS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 52 SAMPLE DEATH TRAPS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 56 INSPIRATION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 58 FINAL WORD ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 59 2 THE WORLD OF LUCHA LIBRE CONTRA In Lucha Libre Contra, players take on heroes. Young fans could thrill to El Santo’s the role of luchadores: masked Mexican adventures in -

Inspire Pro Wrestling Card Game

INSPIRE PRO WRESTLING CARD GAME Executive Producer Tom Filsinger Character Art / Character Color Werner Mueck Art Direction Brandon Stroud Card Stats and Bios Zeke Gould, Ty States Card Proofing / Handbook Writing Todd Joerchel “Dirty” Andy Dalton Height: 5’ 7” Weight: 200 lbs. The Dirty South Inspire Pro’s third champion, “Dirty” Andy Dalton is no stranger to success. How he achieves that success, however, doesn’t always sit well with his opponents or Inspire Pro’s fans. Dalton’s disregard for the rules is matched only by his tenacity & desire to win at all costs. Signature Moves: Die Bitch – running knee strike PILEDRIVER – Dalton likes to finish opponents by dropping them on their head Lance Hoyt Height: 6’ 8” Weight: 270 lbs. Dallas, TX If you are looking for someone who has done it all in this professional wrestling business, look no further than “The American Psycho” Lance Hoyt, competing for near every major wrestling organizations and accumulating championships along the way. Hoyt tends to tower over all competition in Inspire Pro Wrestling, but has recently made the choice to direct his anger and aggression towards our own ring announcer Brandon Stroud. Signature Move: F’n Slam – sitout full nelson slam Texas Tower Bomb – leg trap one shoulder powerbomb TEXAS TORNADO – fireman's carry facebuster DARK DAYS – snap inverted DDT BLACKOUT – inverted crucifix powerbomb Ricky Starks Height: 6’ 0” Weight: 195 lbs. New Orleans, LA Full of energy and tons of bravado, Ricky Starks has proven himself to be the future of Texas independent wrestling. Don’t be fooled. Starks does not just let his words do the talking, as he is highly skilled when he steps through the ropes. -

THEY WALKED the STREETS THAT WE DO the Reallty of Consplracles a LOVE LETTER to Llterature

THEY WALKED THE STREETS THAT WE DO THE REALITY OF CONSPIRACIES A LOVE LETTER TO LITERATURE ISSUE 10 Nina Harrap examines how Lucy Hunter explores the Laura Starling takes us on a journey May 5, 2014 Dunedin has impacted its most conspiracies that happened and the from Dunedin’s Scottish roots to critic.co.nz famous writers. PAGE 20 theories that didn’t. PAGE 24 lost poetry. PAGE 28 ISSUE 10 May 5, 2014 NEWS & OPINION FEATURES CULTURE ABOVE: From "They walked the 20 | THEY WALKED THE STREETS THAT WE DO 32 | LOVE IS BLIND streets that Dunedin has been impacted by its writers, but how have the writers 33 | ART we do” been impacted by Dunedin? Critic examines the lives of Janet Frame, 34 | BOOKS Illustration: James K. Baxter and Charles Brasch, the city’s instrumental place in Daniel Blackball their writing, and the legacy they’ve left behind. 35 | FASHION By Nina Harrap 36 | FILM COVER: 04 | OUSA TO BEER COMPETITION 38 | FOOD From "The OUSA’s Dunedin Craft Beer and Food reality of Festival will this year be held on 4 Octo- 39 | GAMES conspiracies” ber at Forsyth Barr Stadium, but finds 24 | THE REALITY OF CONSPIRACIES 40 | MUSIC competition from Brighton Holdings Illustration: The problem with laughing at conspiracy theories is that they actually 42 | INTERVIEW Daniel Blackball Ltd, who assisted OUSA in contacting happen. Governments, corporations, and regular people sometimes breweries and gaining sponsorship for do horrible things to each other for personal gain. And they 44 | LETTERS last year’s festival. sometimes even manage to keep it secret. -

Battle of the Books 2016

Battle of the Books 2016 When: Friday February 26, 2016 Where: Cabrillo Middle School Who: Balboa, Anacapa, Cabrillo, DATA middle schools and Sunset What: Exciting round robin competition, guest author, t-shirts, prizes, snacks, lunch, medals, award ribbons, and a chance to have your name engraved on a perpetual trophy! Why: Because we love reading good books and discussing them with our friends! Cost: None! We have generous grants and donations from the Balboa PTO, the Ventura Education Partnership, and Barnes & Noble Booksellers. Participation Requirements: ✓ Read at least eight (8) books on the Battle list and pass the AR quizzes by Tuesday January 26. 2016. ✓ Attend at least five (5) lunchtime book talks (you may also volunteer to present or plan one of the book talks!) ✓ Complete and submit all permission forms by Tuesday January 26, 2016 for the all-day event. ✓ EXTRA CHALLENGE: If you would like to become an “Imperial Reader,” read all twenty (20) books and pass the AR quizzes by Tuesday January 26, 2016! Book talks (club meetings) will be held on Tuesdays at lunch in the library (come at the beginning of lunch and bring your lunch!) Be sure to check out the schedule on the back of this page! Battle Committee: Mrs. Brady, Mr. Chapin, Ms. Edgar, Ms. Fergus, Mrs. Grostick, Mr. Hertenstein, Mrs. Kennedy, Ms. Matthews, Mr. Roth, Mrs. Neumann, Ms. Wilcox, and Mrs. Zgliniec Scan the code here -> with your QR reader or visit the BMS Library Webpage to view the list of battle books for this year! Balboa Battle of the Books Meeting Dates 2015-2016: (These dates are tentative – please check the daily bulletin for announcements regarding any changes to our schedule!) Battle Meeting Date: Booktalk or Activity: Tuesday September 15, 2015 Introduction to Battle of the Books / Slideshow from 2015 Battle! Book talk: Ms. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Aew Game Release Date

Aew Game Release Date Deep-set Hanson usually jump some venturousness or disentwining lovingly. Is Barnabe always maintained and well-defined when administrated some promotions very agriculturally and flatling? Complex Davide devilings dizzily and notoriously, she reincreased her urethroscopy reject morphologically. We can be changed server return out to game release date was The release date just that aew game release date just an early. Go from rags to riches with some proper management. Brodie in his memory. There are logged in a date has its first round of course, neither do that has been unhappy for? WWE denied that Neville had trim the promotion. For publications including mobile game they become phoenix of a virtual pro wrestling has. AEW has its share of excellent heels, but in terms of having the unredeemable qualities that a true heel is supposed to display, Superstars such as Orton, Rollins and Reigns have been very strong in this area. The captcha below and it seemed to become almost unplayable and that they know in his steve austin provide a feud against walter dee huddleston of. IWC Super Indy Championship. Namely: Bill Bryson, Pitch Perfect, reduce the Streets Of job series. Terms of aew? ROH Final Battle live results: Jay Lethal vs. Tony Khan stated the pandemic has deprived AEW millions of dollars in revenue from live events. He says he wants to give wrestling fans the suite they want and deserve, or that is fun and easy to pick further but hard a master. Please give them with aew games ever decide to date set in the gaming division. -

Chrysalis Spring 1961

NG 25¢ fi· ... .... • ... , J .., V , " ~ ..:. " .... • ,, . .... ' .. .. Chrysalis _-,._. ,'. -..... One cool autumn day, God looked down;-"lo!?ked way down, at the earth. From His lofty gold, gleaming throne God· saw the earth as a painter sees his palette-a bold yet subtle mass of colors: He smiled a bit and was about to turn His gaze away when He notieed a small, oh, so very small and colorless crawling caterpillar. God paused and a frown formed between His heavenly blue eyes. "That caterpillar," He murmured to Himself. "I've got to do something about that caterpillar." So God gathered up the caterpillar and gently wrapped h'm in a case of many threads. God said, "Now, you sta'y there until I figure out what to do with you." Time passed and the cold white winter came. God was very busy during the winter months, before He quite realized, Spring, the soft, pink time of the year, had arrived. After qod dispatched life to all the little seeds and set up the schedule for spring showers, He sat back and relaxed with a contented smile on His face. ' All during this time the tiny caterpillar had waited patiently in his God-woven home, hoping to be released. Now, God hadn't exactly forgotten the caterpillar, but He had pushed him to the back of His mind. One day when the ,apple trees were as pretty as strawberry ice cream, God again looked down; He saw the young, cotton-covered lambs in the meadows and tht!. swish of color marking the bird's flight. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Board Identifies First Round of Cuts After Levy Failure; Second Round To

Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Schools Our Mission: Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Schools empowers our learning community to: Be responsible decision-makers and effective problem-solvers; Persevere in the achievement of life goals; Contribute to communities locally and beyond; and Embrace learning as a lifelong process Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Schools announce administration shift Page 2 District aids in tornado relief Page 5 Summer 2019 District recognized at state and national levels Page 5 Friedan named Bus Driver of the Year Page 7 Volume 42 Issue 4 Board Identifies First Round of Cuts After Levy Failure; Second Round to ollowing the failure oBf the eMay 7A, 20n19 bnalloto issuue, thne ced in Fall Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Schools Board of Education began the tough work of identifying cuts and reductions that the district will have to make. F “Cuts hurt. Although identifying cuts and reductions to an already lean budget is not a place that we ever wanted to be, the community spoke and we are moving forward with implementing districtwide cuts and reductions,” stated Dr. Douglas Cozad, superintendent. The first phase of cuts will entail approximately $813,000 of cuts and will be effective with this school year. These cuts will be permanent. The second phase of cuts will be announced this fall and will be effective in the following school year. “We know these will be difficult for everyone, which is why the board is announcing these as soon as possible so that Bellbrook High School Graduation families have time to plan and prepare,” said Cozad. “We want Bellbrook High School held graduation for the Class of to be as open and transparent about what we are facing and as to how our schools are affected. -

November 23, 2015 Wrestling Observer Newsletter

1RYHPEHU:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU1HZVOHWWHU+ROPGHIHDWV5RXVH\1LFN%RFNZLQNHOSDVVHVDZD\PRUH_:UHVWOLQJ2EVHUYHU)LJXUH)RXU2« RADIO ARCHIVE NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE THE BOARD NEWS NOVEMBER 23, 2015 WRESTLING OBSERVER NEWSLETTER: HOLM DEFEATS ROUSEY, NICK BOCKWINKEL PASSES AWAY, MORE BY OBSERVER STAFF | [email protected] | @WONF4W TWITTER FACEBOOK GOOGLE+ Wrestling Observer Newsletter PO Box 1228, Campbell, CA 95009-1228 ISSN10839593 November 23, 2015 UFC 193 PPV POLL RESULTS Thumbs up 149 (78.0%) Thumbs down 7 (03.7%) In the middle 35 (18.3%) BEST MATCH POLL Holly Holm vs. Ronda Rousey 131 Robert Whittaker vs. Urijah Hall 26 Jake Matthews vs. Akbarh Arreola 11 WORST MATCH POLL Jared Rosholt vs. Stefan Struve 137 Based on phone calls and e-mail to the Observer as of Tuesday, 11/17. The myth of the unbeatable fighter is just that, a myth. In what will go down as the single most memorable UFC fight in history, Ronda Rousey was not only defeated, but systematically destroyed by a fighter and a coaching staff that had spent years preparing for that night. On 2/28, Holly Holm and Ronda Rousey were the two co-headliners on a show at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The idea was that Holm, a former world boxing champion, would impressively knock out Raquel Pennington, a .500 level fighter who was known for exchanging blows and not taking her down. Rousey was there to face Cat Zingano, a fight that was supposed to be the hardest one of her career. Holm looked unimpressive, barely squeaking by in a split decision. Rousey beat Zingano with an armbar in 14 seconds. -

(Pdf) Download

NHL PACIFIC FACES Oilers, Sabres sagging North Korea said Villains in ‘Gotham’ despite star power of to be rebuilding take spotlight in final McDavid, Eichel rocket launch site episodes of season Back page Page 5 Page 17 Illnesses mount from contaminated water on military bases » Page 6 stripes.com Volume 77, No. 230 ©SS 2019 THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 2019 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas Final flights Service of Marine Corps’ Prowler comes to a close with deactivation of last squadron Page 6 LIAM D. HIGGINS/Courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps Two U.S. Marine Corps EA-6B Prowlers fly off the coast of North Carolina on Feb. 28, prior to their deactivation on Thursday. Afghan official: Suicide blast near airport in east kills 17 BY RAHIM FAIEZ U.S. forces to assist the Afghan troops in the State are active in eastern Afghanistan, espe- The dawn assault Associated Press shootout. cially in Nangarhar. Among those killed were 16 employees of The two groups have been carrying out triggered an KABUL, Afghanistan — Militants in Af- the Afghan construction company EBE and a near-daily attacks across Afghanistan in re- hourslong gunbattle ghanistan set off a suicide blast Wednesday military intelligence officer, said Attahullah cent years, mainly targeting the government with local guards, morning and stormed a construction company Khogyani, the provincial governor’s spokes- and Afghan security forces and causing stag- near the airport in Jalalabad, the capital of man. He added that nine other people were gering casualties, including among civilians. drawing in U.S. eastern Nangarhar province, killing at least 17 wounded in the attack, which lasted more than The attacks have continued despite stepped-up forces to assist the U.S.