Ritualization and Performance of Halumatha Kuruba Identity in Mailaralinga Jatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Meeting Size

Minutes of the 20th Central Sanctioning and Monitoring Committee (CSMC) meeting under Pradhan Manti Awas Yojana (Urban) - Housing for All Mission held on 21st March, 2017 The 20th meeting of the Central Sanctioning and Monitoring Committee (CSMC) under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban) [PMAY(U)] was held on 21st March, 2017 at 10:30 A.M. in the Conference Hall, NBO- Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, with Secretary, Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation in chair. The list of participants is at Annexure-I. 2. At the outset, Secretary (HUPA) welcomed the participants/representatives from the State Governments, participants/officers of the Ministry and other Departments. 3 Thereafter, Joint Secretary (HFA) introduced the agenda for the meeting. The agenda items also form part of the minutes. The item wise minutes are recorded as follows: 4 Confirmation of the minutes of the 19th CSMC meeting under PMAY (U) held on 20th February, 2017 4.1 The minutes of the 19th CSMC meeting under PMAY (U) held on 20th February, 2017 were confirmed without any amendments. Consideration of Central Assistance for 6 Demonstration Housing Projects 5 submitted by Building Materials and Technology Promotion Council (BMTPC). A. Basic Information: The proposal under consideration of CSMC was for Central Assistance for 6 Demonstration Housing Projects of Bihar, Odisha, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Tamil Nadu submitted by BMTPC. To showcase the field application of new emerging technologies, the Ministry has written to various State Governments to participate in the “Demonstration Housing Project” through BMTPC as a part of Technology Sub-Mission. Based on the interest shown and land allotted by the State Governments, BMTPC has taken up Demonstration Housing Projects in few States. -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

1 No. R(2)33/2019-20/PSC Dated : 27/05/19 NOTIFICA

KARNATAKA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION , 'UDYOGA SOUDHA ' BENGALURU - 1 No. R(2)33/2019-20/PSC Dated : 27/05/19 NOTIFICATION ------------ In pursuance of this Office Notification No.R(2)1084/17-18/PSC Dated:23/06/17 the Final Select List of candidates for 100+65(HK) posts of MATHEMATICS TEACHER in the Department of Karnataka Residential Education Institutions Society prepared on the basis of KARNATAKA RESIDENTIAL EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS SOCIETY (C&R) Regulation 2011 as amendment from time to time was published for information of the candidates vide Notification of even number dated 11/02/2018 inviting objections, if any, from candidates within 07 days from date of publication. The objections received within the stipulated time have been examined and the Final Selection list is here by published for information of the candidates. Appointing Authority : EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Name of the Department : Karnataka Residential Education Institutions Society RESIDUAL PARENT CADRE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SL.NO. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE REG.NO. D_O_B RESVN. TPERS QUALIFICATION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 RAVI BALAGAPPANAVAR 1285828 01/06/94 GM/2A/RL 53.89 A R BALAGAPPANAVAR B.Sc with Mathematics AT POST ITAGI B.Ed in Science KHANAPUR BELAGAVI 591112 2 RAJEEV YARADONI 1296121 25/01/87 GM/KMS 53.42 S/O PRAHLAD YARADONI B.Sc with Mathematics NEAR SHRI RAMDEV TEMPLE B.Ed in Science WARD NO. 03 ; MARKET ROAD; ILKAL BAGALKOT 587125 3 MANJUNATH 1313147 01/03/91 GM/2A/RL 51.48 S/O MALLIKARJUN PATTAR B.Sc with Mathematics AT POST YALAGOD B.Ed in Science TQ JEWARGI KALABURAGI 585325 4 SATISHKUMAR BHIMAPPA TANVASHI 1215636 01/06/89 GM/3B/RL 51.38 AT POST ADAHALLI ( TANVASHI TOTA ) B.Sc with Mathematics TQ ATHANI B.Ed in Science DIST BELAGAVI BELAGAVI 591304 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SL.NO. -

A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes Working As Unorganised Labourers

Jenu Kuruba Tribes / 79 A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes working as Unorganised Labourers * Pradeep M D ** Kalicharan M L Abstract Tribals usually are primitive people, living socially as homogeneous unit with their own culture different subsistence pattern, custom, superstitious beliefs, distinct life style living in isolation from outside influence. Forests are closely associated with the tribal economy and culture. Foreign invasion affected tribal life by assimilating through invading their culture. The independent India saw the legal takeover of prime tribal lands in the name of development dispelling millions of tribes. The Government of India adopted a policy to integrate tribes with modernization by encouraging partnership between the tribes and non tribes. The policy of integration or progressive acculturation has laid the foundation for the march of the tribes towards Equality, Upward Mobility, Economic viability and National mainstreaming. The tribes who are very backward are grouped into ‘Primitive Tribes’ having a low level of literacy, declining in population, poor technological access and extreme economic backwardness. Jenu Kuruba Tribes are one of the vulnerable Tribal Groups living in the state of Karnataka. This paper examines the socio-economic life of Jenu Kuruba Tribes covering personal profile, economic condition, literacy, housing pattern and the use of welfare schemes. This research will suggest ways for new interventions to solve the problems through the collective intervention of government officials, local administration, social workers, and the general public. Key Words: Tribes, Culture, Primitive People, Adjustment, Welfare. Introduction The word 'Tribe' is derived from the Latin word 'Tribus' meaning one among the three people, 'Ramayana' denotes 'Jana' the people with different physical appearance, having superstitious beliefs. -

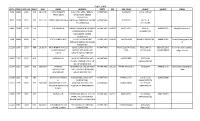

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Price List of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014

Price list of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014 DECCAN COLLEGE POST-GRADUATE AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Deemed University) PUNE 411 006 (INDIA) (1) Terms & Conditions of Sale (This cancels our previous trade terms) Terms 1. Actual postal and packing charges to all orders received from outside India. 2. Postal and packing charges to be borne by the person/institution for all the orders upto Rs. 1000/- in India. 3. Free postal and packing charges to the orders above Rs. 1000/- one time. 4. No discount to individual buyers. 5. 20% discount on all the orders upto Rs. 500/-. 6. 25% discount on all the orders which exceeds Rs. 500/-. 7. Except educational and governmental institutions, books will be supplied ONLY on receipt of Advance Payment against Proforma Invoice. Conditions 1. Out-station buyers should remit the amount, either by M.O. or by Demand Draft drawn on any Nationalized Bank at Pune in the name of ‘Deccan College, Pune’. 2. For the convenience of both the supplier and the buyer and for the early delivery of the books, the books are usually supplied by Registered Book Post marked ‘Printed Books’. 3. Only bulk supply is made by roadways. 4. Books are supplied at buyer’s risk and supplier is not responsible for the books damaged, lost, etc., in transit as also for the delay in delivery of the books. 5. Books once sold and dispatched are not accepted back for any reason on exchanged for other parts. 6. Errors and omissions on the part of the supplier are accepted. 7. Books are not supplied by V.P.P. -

PROFILE of ANANTAPUR DISTRICT the Effective Functioning of Any Institution Largely Depends on The

PROFILE OF ANANTAPUR DISTRICT The effective functioning of any institution largely depends on the socio-economic environment in which it is functioning. It is especially true in case of institutions which are functioning for the development of rural areas. Hence, an attempt is made here to present a socio economic profile of Anantapur district, which happens to be one of the areas of operation of DRDA under study. Profile of Anantapur District Anantapur offers some vivid glimpses of the pre-historic past. It is generally held that the place got its name from 'Anantasagaram', a big tank, which means ‘Endless Ocean’. The villages of Anantasagaram and Bukkarayasamudram were constructed by Chilkkavodeya, the Minister of Bukka-I, a Vijayanagar ruler. Some authorities assert that Anantasagaram was named after Bukka's queen, while some contend that it must have been known after Anantarasa Chikkavodeya himself, as Bukka had no queen by that name. Anantapur is familiarly known as ‘Hande Anantapuram’. 'Hande' means chief of the Vijayanagar period. Anantapur and a few other places were gifted by the Vijayanagar rulers to Hanumappa Naidu of the Hande family. The place subsequently came under the Qutub Shahis, Mughals, and the Nawabs of Kadapa, although the Hande chiefs continued to rule as their subordinates. It was occupied by the Palegar of Bellary during the time of Ramappa but was eventually won back by 136 his son, Siddappa. Morari Rao Ghorpade attacked Anantapur in 1757. Though the army resisted for some time, Siddappa ultimately bought off the enemy for Rs.50, 000. Anantapur then came into the possession of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. -

List of Life Members As on 20Th January 2021

LIST OF LIFE MEMBERS AS ON 20TH JANUARY 2021 10. Dr. SAURABH CHANDRA SAXENA(2154) ALIGARH S/O NAGESH CHANDRA SAXENA POST HARDNAGANJ 1. Dr. SAAD TAYYAB DIST ALIGARH 202 125 UP INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY [email protected] UNIT, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 11. Dr. SHAGUFTA MOIN (1261) [email protected] DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY J. N. MEDICAL COLLEGE 2. Dr. HAMMAD AHMAD SHADAB G. G.(1454) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 31 SECTOR OF GENETICS ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 12. SHAIK NISAR ALI (3769) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCE 3. Dr. INDU SAXENA (1838) ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH 202 002 HIG 30, ADA COLONY [email protected] AVANTEKA PHASE I RAMGHAT ROAD, ALIGARH 202 001 13. DR. MAHAMMAD REHAN AJMAL KHAN (4157) 4/570, Z-5, NOOR MANZIL COMPOUND 4. Dr. (MRS) KHUSHTAR ANWAR SALMAN(3332) DIDHPUR, CIVIL LINES DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY ALIGARH UP 202 002 JAWAHARLAL NEHRU MEDICAL COLLEGE [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 14. DR. HINA YOUNUS (4281) [email protected] INTERDISCIPLINARY BIOTECHNOLOGY UNIT ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 5. Dr. MOHAMMAD TABISH (2226) ALIGARH U.P. 202 002 DEPT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY [email protected] FACULTY OF LIFE SCIENCES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY 15. DR. IMTIYAZ YOUSUF (4355) ALIGARH 202 002 DEPT OF CHEMISTRY, [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH, UP 202002 6. Dr. MOHAMMAD AFZAL (1101) [email protected] DEPT. OF ZOOLOGY [email protected] ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202 002 ALLAHABAD 7. Dr. RIAZ AHMAD(1754) SECTION OF GENETICS 16. -

State: KARNATAKA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: BIJAPUR

State: KARNATAKA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: BIJAPUR 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro -Climatic/Ecological Zone Agro Ecological Sub Region Deccan Plateau, hot semi arid ecosub region ( 6.1 ) (ICAR) Agro-Climatic Region (Planning Southern Plateau and Hill Region (X) Commission) Agro Climatic Zone (NARP) Northern Dry Zone (KA-3) List all the districts or part thereof Entire District: Bijapur, Bagalkot, Gadag, Bellary, Koppal falling under the NARP Zone Part of District: Belgaum, Dharwad, Raichur, Davanagere Geographic coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude 16º 49'N 75º 43'E 593 .0 m Name and address of the Regional Agricultural R esearch Station, P. B.No. 18 concerned ZRS/ ZARS/ RARS/ BIJAPUR - 586 101 RRS/ RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Bijapur 1.2 Rainfall Average (mm) Normal Onset Normal Cessation SW monsoon (June-Sep): 387.5 2 nd week of June NE Monsoon (Oct -Dec): 130 .0 4 th week of October to 4 th week of November Winter (Jan- Feb) 6.8 - - Summer (Mar-May) 56.1 - - Annual 594.4 - - 1.3 Land use Geographical Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other pattern of area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows the agricultural Misc. tree Land district use crops and groves Area 1053.5 2.0 35.8 9.6 5.5 1.3 29.1 85.3 5.7 (‘000 ha) 1. 4 Major Soils Area (‘000 ha) Percent (%) of total Medium black soils 401.3 40 Shallow black soils 262.5 26 Deep black soils 234.2 23 Red loamy soils 48.1 5 Red sandy soils 20.2 2 Red and -

Legend Shingrahalli Satturu

Village Map of Ballari District, Karnataka µ Thasalakudlura Maturu Vatthumuravani Hachholli Beeravalli Kallukutiginahalu Basarahalli Honnarahalli Chikkabellary HalumuravaniAkkathangerahalu Halekote Halekota Byragamadhinni Seedharagudda Kotthalachintha Gubbihalu Kesarakona Kudadharahalu HACHCHOLLI Ravihalu Bommalapura Nagalapura Mittesugura Bagewadi Matradhinni VenkatapuraNagarahalu Kuruvalli Agasanura Alabanuru Bagewadi Gajaginahalu T.Rampura Bevinamarada-Suguru Karchiganura Nadanga Dhesanuru Ibrahimapura Itgihalu Thondehalu SIRUGUPPA Janakanura Siraguppa Siraguppa Raravi Siraguppa Baggura Kenchanagudda Devalapura Saliganuru Araliganuru Kotehalu Herakallu Bandralu Manjinahalu K.Suguru Herakallu Halekote Poppanahalu (Inam) Hirehalu Siraguppa Nittura ThekkalakoteUpparahosahalli Mudhenura K.Belagallu Udegola Upparahosahalli Thekkalakote Balakundhi Mylapura Kenchagarabelagal TEKKALAKOTE Nadavi Boodhiguppa Balakundhi Kuriganuru Boodhiguppa M.Sugura Malapura Mannuru KARURU Matasugura Gosabalu Muddatanuru Byrapura Itagi Sirageri Utthanuru Siddaramapura Karura Belagoduhalu Sanapura Havinahalu Yammiganuru Uluru Muddhapura (2) Dasapura Belagoduhalu Aralihalli Dharura Gundiganuru Syanavasapura H.Veerapura Konchigeri Kyadhagihalu Hagalura Kampli Thalura Kampli Kampli Nalludi Chitakinahalu H.Hosahalli Yammiganuru Genikehalu Somalapura Ramasagara Muddhapura (10) Mushtagatti Sindhigeri Karikeri Chananahalu Bukkasagar Hirehadagali Kampli Devasamudra Chikka Jayaganuru Kurugodu Bukkasagar K.Thimmalapura Hire Jayaganuru Gutthiganuru Byluru KallukambaLakshmipura -

KARNATAKA DATA HIGHLIGHTS: the SCHEDULED TRIBES Census

KARNATAKA DATA HIGHLIGHTS: THE SCHEDULED TRIBES Census of India 2001 The total population of Karnataka, as per 2001 Census is 52,850,562. Of this, 3,463,986 are Scheduled Tribes (STs). The ST population constitutes 6.6 per cent of the state population and 4.1 per cent of the country’s ST population. Forty-nine STs have been notified in Karnataka by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Order (Amendment) Act, 1976 and by the Act 39 of 1991. This is the second highest number, next to Orissa (64) if compared with the number of STs notified in any other states/UTs of the Country. Five STs namely, Kammara, Kaniyan, Kuruba, Maratha and Marati have been notified with area restriction. Kuruba and Maratha have been notified only in Kodagu district, where as Marati in Dakshina Kannada, Kaniyan in Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar and Kammara in Dakshina Kannada and Kollegal taluk of Chamarajanagar districts of Karnataka. 2. Of the STs, two namely, Jenu Kuruba and Koraga are among the Primitive Tribal Groups (PTGs) of India having population of 29,828 and 16,071 respectively in 2001 Census. Jenu Kuruba are mainly distributed in Mysore, Kodagu and Bangalore districts, and Koraga in Dakshina Kannada and Dharward districts. In the present census, a low growth rate of 1.6 per cent and a negative growth rate of 1.5 per cent have been reported for the Jenu Kuruba and Koraga respectively. 3. The growth rate of ST population in the decade 1991-2001 at 80.8 per cent is considerably higher in comparison to the overall 17.5 per cent of state population. -

Census of India 2001 General Population Tables Karnataka

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 GENERAL POPULATION TABLES KARNATAKA (Table A-1 to A-4) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KARNATAKA Data Product Number 29-019-2001-Cen.Book (E) (ii) CONTENTS Page Preface v Acknowledgement Vll Figure at a Glance ]X Map relating to Administrative Divisions Xl SECTION -1 General Note 3 Census Concepts and Definitions 11-16 SECTION -2 Table A-I NUMBER OF VILLAGES, TOWNS, HOUSEHOLDS, POPULATION AND AREA Note 18 Diagram regarding Area and percentage to total Area State & District 2001 19 Map relating to Rural and Urban Population by Sex 2001 20 Map relating to Sex ratio 2001 21 Diagram regarding Area, India and States 2001 22 Diagram regarding Population, India and States 2001 23 Diagram regarding Population, State and Districts 2001 24 Map relating to Density of Population 25 Statements 27-68 Fly-Leaf 69 Table A-I (Part-I) 70- 82 Table A-I (Part-II) 83 - 98 Appendix A-I 99 -103 Annexure to Appendix A-I 104 Table A-2 : DECADAL VARIATION IN POPULATION SINCE 1901 Note 105 Statements 106 - 112 Fly-Leaf 113 Table A-2 114 - 120 Appendix A-2 121 - 122 Table A-3 : VILLAGES BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS Note 123 Statements 124 - 128 Fly-Leaf 129 Table A-3 130 - 149 Appendix A-3 150 - 154 (iii) Page Table A-4 TOWNS AND URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS IN 2001 WITH VARIATION SINCE 1901 Note 155-156 Diagram regarding Growth of Urban Population showing percentage (1901-2001) 157- 158 Map showing Population of Towns in six size classes 2001 159 Map showing Urban Agglomerations 160 Statements 161-211 Alphabetical list of towns.