1 a Conversation with Michelle Shocked by Frank Goodman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAR CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 20 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 18, 19 BENNY BENASSI DA 16 THE CLARK SISTERS GS 14 EST GEE HS 4; H100 34; ODS 14; RBH 17; RS H.E.R. B200 166; RBL 23; ARB 12, 14; H100 50; -L- 13; STM 13 HA 23; RBH 22; RBS 6, 18 THE 1975 RO 40 GEORGE BENSON CJ 3, 4 CLEAN BANDIT DES 16 LABRINTH STX 20 FAITH EVANS ARB 28 HIKARU UTADA DLP 17 21 SAVAGE B200 63; RBA 36; H100 86; RBH DIERKS BENTLEY CS 21, 24; H100 -

Gillian Welch's Long-Awaited New Album

FREE JULY 2011 Readings Monthly • • • Peter Salmon Ann Patchett Alan Hollinghurst Robert Hughes (SEE P18) THE HARROW AND HARVEST IMAGE FROM GILLIAN WELCH'S NEW ALBUM Gillian Welch’s long-awaited new album p 17 Highlights of July book, CD & DVD new releases. More inside. NON-FICTION AUS FICTION FICTION FICTION YA DVD POP CD CLASSICAL $50 $39.95 $29.99 $24.95 $30 $24.95 $33 $27.95 $19.95 $24.95 $25.95 $21.95 $24.95 >> p19 >> p5 >> p6 >> p7 >> p8 >> p14 >> p16 (for July) >> p17 July event highlights : Matthew Evans on Winter on the Farm. James Boyce at Readings Carlton, Favel Parrett, Rosalie Ham. See more events inside. All shops open 7 days, except State Library shop, which is open Monday - Saturday. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 Port Melbourne 253 Bay St 9681 9255 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 email us at [email protected] Browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au and at ebooks.readings.com.au travel card travel card Instant WIN a $10,000 4000 1234 5678 9010 4000 5678 9010 4000 1234 4000 GOOD THRU 00/00 GOOD THRU 00/00 ANZ Travel Card It’s money made to travel Purchase any Lonely Planet product with a promotional sticker from 9am 04/06/11 until ANZ Travel Card ANZ Travel Cards 5pm 31/07/11 and visit lonelyplanet.com/anztravelcard to be in the running to win.. -

Ruination Day”

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Fernandez, “Ruination Day” “Ruination Day”: Gillian Welch, Woody Guthrie, and Disaster Balladry1 Mark F. Fernandez Disasters make great art. In Gillian Welch’s brilliant song cycle, “April the 14th (Part 1)” and “Ruination Day,” the Americana songwriter weaves together three historical disasters with the “tragedy” of a poorly attended punk rock concert. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and the epic dust storm that took place on what Americans call “Black Sunday” in 1935 all serve as a backdrop to Welch’s ballad, which also revolves around the real scene of a failed punk show that she and musical partner David Rawlings had encountered on one of their earlier tours. The historical disasters in question all coincidentally occurred on the fourteenth day of April. Perhaps even more important, the history of Welch’s “Ruination Day” reveals the important relationship between history and art as well as the enduring relevance of Woody Guthrie’s influence on American songwriting.2 Welch’s ouevre, like Guthrie’s, often nods to history. From the very instruments that she and Rawlings play to the themes in her original songs to the tunes she covers, she displays a keen awareness and reverence for the past. The sonic quality of her recordings, along with her singing and musical style, also echo the past. This historical quality is quite deliberate. Welch and Rawlings play vintage instruments to achieve much of that sound. Welch’s axes are all antiques—her main guitar is a 1956 Gibson J-50. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

Coming up at the Aquarium Tickets at Dempsey's, Orange Records and Ticketweb.Com • 21+ Upstairs at 226 Broadway in Fargo • Online at Aquariumfargo.Com

COMING UP AT THE AQUARIUM TICKETS AT DEMPSEY'S, ORANGE RECORDS AND TICKETWEB.COM • 21+ UPSTAIRS AT 226 BROADWAY IN FARGO • ONLINE AT AQUARIUMFARGO.COM SIMON JOYNER & THE GHOSTS • THURSDAY, JUNE 6 MAUNO • MONDAY, JUNE 24 Lo-fi folk cited as an influence by Conor Oberst, Idiosyncratic, tumbling indie pop w/ plumslugger, Gillian Welch, Kevin Morby and Beck w/ Parliament Lite and Bryan Stanley (First show! Richard Loewen and Walker Rider • Doors @ 8 Backed by members of Naivety ) • Doors @ 8 MUSCLE BEACH + MCVICKER • FRIDAY, JUNE 7 ROYAL TUSK • THURSDAY, JUNE 27 A double dose of noisy Minneapolis Blue-collar troubadours merging riffy hooks punk rock n roll w/ locals Under Siege, with a thick bottom end and loud-as-hell guitars Plumslugger and HomeState • Doors @ 9 w/ The Dose • Jade Presents event • Doors @ 7 EMO NIGHT • SATURDAY, JUNE 8 MEGAN HAMILTON • FRIDAY, JUNE 28 Drink some drinks, dance, hang out and have Funky house tunes w/ SLiPPERS, Force Induction, some fun singing along to all your favorite early DeziLou, 2Clapz and Alex Malard • Playback 2000s emo jams • No cover • Starts @ 10 Shows + Wicked Good Time event • Doors @ 9 PAPER PARLOR + STOVEPIPES • SUNDAY, JUNE 9 JESSICA VINES + KARI MARIE TRIO • SATURDAY, JUNE 29 Psychedelic blues fusion jam rockers Guitar-driven, poppy, funky, rockin’ R&B + piano comin' in hot from Duluth + local blues rock from members of The Human Element and rock favorites Stovepipes • Doors @ 8 Hardwood Groove among others • Doors @ 8 HIP-HOP + COMEDY NIGHT • FRIDAY, JUNE 14 YATRA + GREEN ALTAR • SUNDAY, JUNE 30 Music by Durow, X3P Suicide, Stan Cass and Stoner, sludge and doom metal from Baltimore and DJ Affilination. -

Michelle Shocked Short Sharp Shocked Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michelle Shocked Short Sharp Shocked mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Short Sharp Shocked Country: Thailand Style: Folk Rock, Country Rock, Acoustic MP3 version RAR size: 1801 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1931 mb WMA version RAR size: 1711 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 556 Other Formats: ADX MPC WAV DMF WMA MMF DTS Tracklist A1 When I Grow Up A2 Hello Hopeville A3 Memories Of East Texas A4 (Make The Run To) Gladewater A5 Graffiti Limbo B1 If Love Was A Train B2 Anchorage B3 The L&N Don't Stop Here Anymore B4 V.F.D. B5 Black Widow Credits Producer, Arranged By – Pete Anderson Notes Black cassette with blue & white paper labels. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Short Sharp Shocked (CD, 834 924-2 Michelle Shocked Mercury 834 924-2 US 1988 Album) Short Sharp Shocked (Cass, 834 924-4 Michelle Shocked Mercury 834 924-4 Canada 1988 Album, Dol) 834 924-2 Michelle Shocked Short Sharp Shocked (LP, TP) Mercury 834 924-2 Greece 1988 Short Sharp Shocked (LP, 834 924-1 Michelle Shocked Mercury 834 924-1 Portugal 1988 Album) Short Sharp Shocked (CD, 834 924-2 Michelle Shocked Mercury 834 924-2 Europe Unknown Album, RE, RP) Related Music albums to Short Sharp Shocked by Michelle Shocked Michelle Shocked - If Love Was A Train Mac - Shell Shocked Michelle Shocked - (Don't You Mess Around With) My Little Sister Various - Cooking Vinyl - 1993 Sampler Volume 2 Michelle Shocked - On The Greener Side Michelle Shocked - When I Grow Up Dee Dee Sharp - All The Hits By Dee Dee Sharp Brandon Cooke - Sharp As A Knife (Remix) Michelle Shocked - Arkansas Traveler Michelle Shocked - Anchorage Kylie - Shocked Kylie Minogue - Shocked. -

The On-Line Guitar Archive

OLGA - The On-Line Guitar Archive The On-Line Guitar Archive - Search The Archive 06/21/2005 28118 files (3186 bass) About Submit FAQs Chat OLGA Your Tab Why Do People Contribute To Browse The Archive OLGA? (09 Apr 05) Turns out an academic paper has been Guitar Tab written on the subject (we knew nothing Everything about it) in the Journal of Computer- Classical Mediated Communication. Thanks to All Resources Natalie Guinsler for passing this on. Lessons Firefox Search Construction New Files Plugin (31 Jan 05) Don't know the Has your submission been Are you using chords? Check out ... archived? We are archived Firefox and need The LARGE Chord through: 11 Jun 05 an even faster way to find tab? Thanks Dictionary Check New In Jun | May to Alan Bramley, you can add OLGA to your search box. Haven't given or use the chord Yeah, We Got That Firefox a try yet? You can download it generator, Roots and Offshoots | for free from mozilla.org. thanks to Jim Cranwell. Rodney Crowell | Steve Earle | Click here if above Alison Krauss | Jayhawks | Complete Beatles (14 Dec 04) doesn't work. Uncle Tupelo | Gillian Welch | Right-click or control-click for a Beatles Wilco | Lucinda Williams songbook in pdf format. Thanks to For tab files, read the... Sergio Palumbo. Guide To Reading Modern Rock | Audioslave | Tablature Beck | Blink 182 | Breaking Benjamin | Chevelle | or try Derek Coldplay | Crossfade | Foo Stottlemyer's | | Fighters Garbage Green TabSMART Software Day | Jimmy Eat World | Killers | Linkin Park | Mars there's also Jim Volta | Modest Mouse | Cranwell's web-based Mudvayne | Nickelback | NIN | tabbing app Nirvana | Offspring | P. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

The Lowhills Song List October 2018

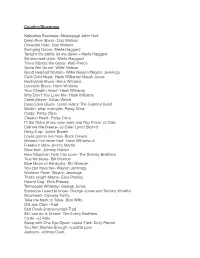

Country/Bluegrass Nobodies Business- Mississippi John Hurt Deep River Blues- Doc Watson Crawdad Hole- Doc Watson Swinging Doors- Merle Haggard Tonight the bottle let me down – Merle Haggard Sit here and drink- Merle Haggard There Stands the Glass- Web Pierce Gotta Get Drunk- Willie Nelson Good Hearted Woman- Willie Nelson/Waylon Jennings Cold Cold Heart- Hank Williams/ Norah Jones Honkytonk Blues- Hank Williams Lovesick Blues- Hank Williams Your Cheatin Heart- Hank Williams Why Don’t You Love Me- Hank Williams Caleb Meyer- Gillian Welch Deep Elem Blues- Levon Helm/ The Grateful Dead Walkin’ after midnight- Patsy Cline Crazy- Patsy Cline Cheatin Heart- Patsy Cline I’ll Be There (if you ever want me) Ray Price/ JJ Cale Call me the breeze- JJ Cale/ Lynrd Skynrd Hung it up- Junior Brown Loves gonna live here- Buck Owens Women I’ve never had- Hank Williams Jr Freeborn Man- Jimmy Martin Slew foot- Johnny Horton How Mountain Girls Can Love- The Stanley Brothers True life blues- Bill Monroe Blue Moon of Kentucky- Bill Monroe You can have her- Waylon Jennings Wurlitzer Prize- Waylon Jennings That’s alright Mama- Elivs Presley Hound Dog- Elvis Presley Tennessee Whiskey- George Jones Someone I used to know- George Jones and Tammy Winette Slowhand- Conway Twitty Take me back to Tulsa- Bob Wills Old Joe Clark -Trad Salt Creek (instrumental)-Trad All I can do is Dream- The Everly Brothers Clyde –JJ Kale Sleep with One Eye Open- Lester Flatt/ Dolly Parton You Aint Woman Enough –Loretta Lynn Jackson- Johnny Cash Folsom Prison- Johnny Cash Big River-Johnny -

New York's Raucus Campaign

OBSER VER Volume 16, Number 6 College at Lincoln Center, Fordham University, New York April 15, 1992 CONGRESS USG PROPSES CONSIDERS HIGHER EflSINGLIMIT ACTIVITY FEE ON RID By Anastasla Damlanakos The United Student Government met on FArr-"B"f agteagMsa—^-^: .- April 8th to discuss several proposals. The agenda included the first draft of the new Constitution, plans for Senior week, a proposed increase of the student activity fee, and future plans for the the Student Lounge. Although many senators did not attend, =_= z —"•fir ~* • • » • this meeting was crucial in deciding the budget for USG. The Student Activity fee may be increased up to $75 by Fall 1993. "We desperately need the money... it would make the quality of life at Fordham a little p*«r« »j ««j Locke The Council also announced allocation of beds in the donn bit better", said Freshman senator Mike Murray. A petition for the increase has to be signed by 15 percent of the undergraduate student body ( 265 students) before it goes into effect. COLLEGE COUNCIL DISCUSSE The Student Lounge will be furnished will a VCR , a television.and a a stereo sound system if the Fall budget allows. QUINN MEMORIAL The Senior Week cruise will cost $60 per Sheila Harris beds which students can choose on a fust .ticket. Plans to name the Lowenstein Library after come first serve basis. the late Dr. Gerald M. Quinn, Dean of CLC, CLC was allocated 295 out of the 400 beds phmtm by Roy Loekt and the status of the new Lincoln Center that were asked for, said Bristow, and along By Sean Gallagher Dormitory were some of the topics discussed with the pooled beds, CLC should have from G.R.E. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Michelle Shocked Captain Swing Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michelle Shocked Captain Swing mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Blues / Folk, World, & Country Album: Captain Swing Country: Canada Released: 1989 Style: Jump Blues, Folk, Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1339 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1133 mb WMA version RAR size: 1154 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 653 Other Formats: VOC VOX MP1 MP2 AC3 DXD MPC Tracklist A1 God Is A Real Estate Developer A2 On The Greener Side A3 Silent Ways A4 Sleep Keeps Me Awake A5 The Cement Lament B1 (Don't You Mess Around With) My Little Sister B2 Look's Like Mona Lisa B3 Too Little Too Late B4 Streetcorner Ambassador B5 Must Be Luff Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – PolyGram Records, Inc. Manufactured For – Polygram Inc. Distributed By – PolyGram Distribution Inc. Credits Accordion – Zachary Richard Baritone Saxophone, Clarinet – Beverly Dahlke-Smith Bass – Dominic Genova, Dusty Wakeman Drums – Jeff Donavan Guitar – Pete Anderson Keyboards – Skip Edwards Mandolin – Paul Glasse Mastered By – Stephen Marcussen Percussion – Lenny Castro Producer, Arranged By – Pete Anderson Programmed By – John Begzian Tenor Saxophone – Steve Grove Trombone – David Stout Trumpet – Lee Thornburg Tuba – Freebo Violin – Don Reed Vocals, Acoustic Guitar – Michelle Shocked Written-By – Michelle Shocked Notes ℗ 1989 PolyGram Records, Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 422-838878-4 8 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Michelle Captain Swing (LP, 838 878-1 Mercury 838 878-1 Canada 1989 Shocked Album) Michelle Captain Swing