Collective Action for Forest Protection and Management by Rural Communities in Orissa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming Towards a Resilient, Responsible and Reliable Future

Content 04 Chairman’s Statement 05 About the Report 06 Message from the Managing Director Transforming 08 Message from Chief Sustainability Officer 10 Leaders Speak towards a Resilient, 12 Key Highlights 14 About Hindalco Responsible and 19 Stakeholder Engagement and Materiality Analysis 24 Resilient Reliable Future 25 Corporate Governance We, at Hindalco, are on a path of transformation. As stakeholder 31 Risk Management Framework expectations evolve and resources become scarce, adopting sustainable business practices has become an imperative to future-proof the Company. 34 Economic Stewardship We operate with an integrated business model, ranging from bauxite 38 Responsible and coal mining to the production of value-added aluminium and copper products. This involves exposure to an ever-evolving business environment 39 Responsible Mining at both national and global levels. Considering these variations in the business environment, we have continued our focus on strengthening 44 Environmental Stewardship systems and frameworks. This helps us in improving the business 74 Health and Safety performance, while developing resilient corporate governance and risk management practices. 80 Community Stewardship Since we belong to a resource-intensive industry involving complex operations, the focus on environment, society, and health and safety is 94 Reliabe of paramount importance for us. We understand our responsibility in 95 Employee Stewardship addressing the environmental and social impacts of our operations and take necessary steps to minimise them. In order to ensure a safe workplace, 116 Product Stewardship we constantly strive to improve our health and safety performance. Our initiatives in the areas of environment, community stewardship, and health 123 Customer Centricity and safety as outlined in this report demonstrate our approach towards 125 Supply Chain Management operating in a responsible manner. -

The Orissa G a Z E T T E

The Orissa G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 1671 CUTTACK, MONDAY, JULY 18, 2011 / ASADHA 27, 1933 HOUSING & URBAN DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 15th July 2011 S.R.O. No. 604/2011–Whereas, the draft notification for the purpose of inclusion of additional 67 (sixty-seven) Revenue Villages in Sambalpur Development Area declared as such in the Notification of the Government of Orissa in the Housing & Urban Development Department No. 22060-HUD., dated the 3rd June 1989 was published as required by Section 1 of Rule 3 of the Orissa Development Authorities Rules, 1983 in the Extraordinary issue of the Orissa Gazette No. 1983, Dt. 26-11-2010 under the Notification of the Government in the Housing & Urban Development Department No. 24592, Dt. 11-11-2010 ; And whereas, no objection and suggestion was received in respect of the said draft before the expiry on the date specified by the State Government in the said Notification ; Now, therefore, in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (2) of Section 3 of the Orissa Development Authorities Act, 1982 and in partial modification to the Government of Orissa in the Housing & Urban Development Department Notification No. 22060, Dt. 3-6-1989, the State Government do hereby declare that the existing Sambalpur Development Area shall include the additional areas of the Revenue villages as mentioned in Col.(2) of Schedule-I below ; and accordingly the boundaries of Sambalpur Development Area shall be described in Schedule-II below : SCHEDULE-I Sl. Name of the Name of the Police Name of the Urban Local No. -

Officename a G S.O Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Kharavela Nagar S.O Orissa Assembly S.O Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Old Town S.O (Khorda

pincode officename districtname statename 751001 A G S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Kharavela Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Orissa Assembly S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Khorda ODISHA 751002 Old Town S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751002 Harachandi Sahi S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kedargouri S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Santarapur S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bhimatangi ND S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Gopinathpur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Itipur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kalyanpur Sasan B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kausalyaganga B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kuha B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sisupalgarh B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sundarpada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bankual B.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Baramunda Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Suryanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751004 Utkal University S.O Khorda ODISHA 751005 Sainik School S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Budheswari Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Kalpana Square S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Laxmisagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Jharapada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Station Bazar B.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Saheed Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Satyanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751007 V S S Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751008 Rajbhawan S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bapujee Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bhubaneswar R S S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Ashok Nagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Udyan Marg S.O Khorda ODISHA 751010 Rasulgarh S.O Khorda ODISHA 751011 C R P Lines S.O Khorda ODISHA 751012 Nayapalli S.O Khorda ODISHA 751013 Regional Research Laboratory -

Chapter 8 Industry Sector: Sambalpur

CHAPTER 8 INDUSTRY SECTOR: SAMBALPUR 8.1 Background Sambalpur is an agrarian economy and it is not mineral rich. Rice milling and sponge iron dominate the industrial sector. There are, however, developments which will give fillip to its industrial growth. 8.2 Mining Sambalpur is not a significant mining area of Orissa, as is evident from the following. There is one coal mining lease in Sambalpur amounting to over 170 ha. Sambalpur accounts for 1.32% and 4.6% of mining leases in Orissa in terms of number and area respectively. There is some china clay mining in Sambalpur. The mining activity profile of the district is as follows. Traders : 210 Storage Depots : 9 Processing Units : 14 Mineral based Industries : 130 Total Enterprise : 363 Sambalpur is the headquarters of Mahanadi Coalfields Limited (MCL). It is one of the eight subsidiaries of Coal India Limited. It has its coal mines spread across Orissa. It has total seven open cast mines and three underground mines under its fold. MCL has two subsidiaries with private companies as a joint venture. These are MJSJ Coal Limited & MNH Shakti Ltd. The net operating revenue of MCL during 2010-11 was Rs. 9359 crores. It employed 21425 persons (Chart 8.1). Chart 8.1 Mining Status: Sambalpur _____________________________________________________________________208 Draft CDP Comprehensive Development Plan, Sambalpur 8.3 Medium And Large Industry Sponge iron dominates the medium and large industry sector. There are 10 sponge iron industries; which have a direct reduction kiln capacity of 5000 tons per day. The share of Bhushan Ltd in this is 40%; Viraj Steel and Energy and Shyam DRI Power being the other significant players (14% each). -

Application Form-1

Application Form-1 Request for EC Amendment at Existing Smelter and Captive Power Plant, Unit - Aditya Aluminium Lapanga Village, Rengali Tehsil, Sambalpur District, Odisha Project Proponent: M/s Hindalco Industries Ltd (Unit - Aditya Aluminium) P.O. - Lapanga, District – Sambalpur, Odisha - 768212 August, 2017 Form-1 for EC Amendment Proposal at Existing Smelter and Captive Power Plant, Lapanga Village, Rengali Tehsil, Sambalpur District, Odisha of Unit-Aditya Aluminium of M/s Hindalco Industries Ltd. APPLICATION FORM 1 (Submitted as per EIA Notification 2006 and Amendments thereof) I Basic Information S. No. Item Details 1 Name of the project Request for amendment of EC at existing integrated Smelter and Captive Power Plant (CPP) at Lapanga in Sambalpur district of Odisha State by Aditya Aluminium Unit (AA) of M/s Hindalco Industries Ltd. (HIL) 2 S. No in the schedule 1(d) and 3(a) 3 Proposed capacity/ area /length/ 1. Change in Coal Source to CPP as tonnage to be handled/ command proposed in EC : Based on the present area/ lease area/ number of well to practical scenario, 0-20% of imported coal be drilled and 80-100% of Indian domestic coal (from own mines, linkage & e-auction coal, coal from open market and e-auction) has been proposed. 2. Pot Production enhancement - Upgradation of amperage : Increment in Production Level of Smelter from 360 to 380 KTPA. 3. Selling of molten metal, baked anodes and bath material - it is proposed to sell about 75 KTPA Hot metal, approx. 5,000 nos. of the generated anode and 1,500 TPA of the generated bath material to private parties. -

Thermal Power Plants in Odisha

Thermal Power Plants in Odisha Sl. Name Address & Contact Generation No. Person with E-mail-id Capacity in MW 1. M/s Aarti Steel Ltd. At-Ghantikhala, 80 Po- Mahakalabasta, Athagada, Cuttack Mr. Pritish Dash, Manager (Env.) [email protected] M-9437083942 2. M/s ACC Ltd. Bargarh Cement Works, 30 Cement Nagar, Bardol, Bargarh, Pin No. 768 038, Ph No. 91-6646-247161, Fax. 91-6646-246430 Mr. Debapratim Bhadra, Head- Energy & Env. debapratim.bhadra@accli mited.com M-9777447636 arupkumar.das@acclimite d.com 3. M/s Action Ispat & Power At: Pandripathar, 63 (P) Ltd. P.O. Marakuta, Dist-Jharsuguda, Pin No. 768202 Mr. BhabyaRanjan Nayak, Environment Dept. environment.bhabyaranja [email protected] Mr. Ranjan Sahu Asst. Env. Officer, M-7752023544 [email protected] om 4. M/s Bhushan Power & Vill-Thelkoloi, 370 Steel Ltd. P.O. Lapanga- 768232 Teh. Rengali, Dist-Sambalpur, Mr. Niranjan Parida, Dy. Manager, [email protected] M-9437150569 Sl. Name Address & Contact Generation No. Person with E-mail-id Capacity in MW 5. M/s Bhushan Steel Ltd. At- Narendrapur, 142 Meramundali, Dhenkanal Ph. No. 06762-300000 / 660002 / 660000, Fax. 91-011-66173997 Mr. Santosh Pattajoshi, Sr. Manager, santosh.pattajoshi@bhusha nsteel.com M-7077757663 ram.sharma@bhushansteel .com 6. M/s Bhushan Energy Ltd. At-Ganthigadia, 300 P.O. Nuahata, Via-Banarpal, Dist-Angul Pin No. 759128 Ph-6762-300000 Fax. 011-66173997 7. M/s Birla Tyres At/Po-Chhanpur, Kuruda, 20 Balasore-756056, Ph. No. 06782- 254621/254225, Fax.06782-254225 Mrs. Suchismita Patnaik, Team Member, suchismita_patnaik@birlaty re.com 8. -

Tender Specification Bhel: Pssr: Sct: 1876

TENDER SPECIFICATION BHEL: PSSR: SCT: 1876 FOR Dismantling of Office shed of approximate size 10M x 40M x 3.0M at Aditya CPP, Hindalco at Lapanga in Sambalpur district at Odisha (excluding foundation), Transportation to 5 X 800 MW Yadadri Thermal Power Plant at Telangana, re-erection including supply of items required for complete readiness of the shed (Excluding foundation) at 5 X 800MW Yadadri TPS Veerlapalem Village, Dameracherla Mandal, Nalgonda Dist, Telangana State TECHNOCOMMERCIAL BID - Consists of Book- I & Book- II Book- I Consists of o Notice Inviting Tender o Volume-IA: Technical Conditions of Contract Book-II consists of o Volume-IB: Special conditions of Contract, Rev 01 dated 1st June 2012 st Amendment 01 dated 1 October, 2015 o Volume-IC: General conditions of Contract Rev 01 dated 1st June 2012, st Amendment 03 dated 1 October, 2015 o Volume-ID: Forms & Procedures Rev 01 dated 1st June 2012 Amendment 01 dt 1st October, 2015 VOLUME –I BOOK – I BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED (A Government of India Undertaking) Power Sector – Southern Region 690, Anna Salai, Nandanam, Chennai – 600 035. TENDER SPECIFICATION CONSISTS OF Tender Specification Volume - I Book-I Notice Inviting Tender Volume-IA: Technical Conditions of Contract Part I Part II Book-II Volume-IB: Special conditions of Contract Rev 01 dated 1st June 2012 Amendment 01 dated 1st October 2015 Volume-IC: General conditions of Contract Rev 01 dated 1st June 2012, Amendment 03 dated 1st October, 2015 Volume-ID: Forms & Procedures Rev 01 dated 1st October, 2015 Amendment -

Final Draft of CEA Anual Report 2019-20

CEA ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 CENTRAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF POWER The AUTHORITY (As on 31.03.2020) Sh. Prakash Mhaske Chairperson & Addl. Charge of Member (Power System) Dr. Somit Dasgupta Sh. P.D. Siwal Member (E&C) Member (Thermal) (upto 31.12.2019) (upto 29.02.2020) Sh.Sandesh Kumar Sharma Sh. Dinesh Chandra Member (Planning) Member (Hydro) Addl.charge Member(E&C) Addl.Charge of Member (GO&D) ORGANIZATION CHART OF CEA (AS ON 31.03.2020) CHAIRPERSON (Prakash Mhaske) MEMBER MEMBER MEMBER MEMBER MEMBER MEMBER (THERMAL) (HYDRO) (POWER SYSTEM) (GRID OPN. & (ECONOMIC & COMM.) (PLANNING (P.D. Siwal) (Dinesh Chandra) Addl. Charge DISTN.) (Dr. Somit Dasgupta) (Sandesh Kumar Sharma) with Chairperson, CEA Addl. Charge with (प्रकाश मके) CHIEF ENGINEER PRINCIPAL CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER PRINCIPAL CHIEF ENGINEER (INTEGRATED (HYDRO (POWER SYSTEM (FINANCIAL CHIEF ENGINEER-I (THERMAL CHIEF ENGINEER–II SECERETARY RESOURCE ENGINEERING AND PLANNING & STUDIES & (Chander Shakhar) PROJECT (B.K. Sharma) (P.C. KUREEL) PLANNING) RENOVATION & APPRAISAL-I) ANALYSIS) MONITORING-I) MODERNIZATION) CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER (FUEL CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER (GRID CHIEF ENGINEER (COORDINATION) MANAGEMENT) (THERMAL CHIEFI ENGINEER (POWER SYSTEM MANAGEMENT) (FINANCIAL & PROJECT APPRAISAL PROJECT (HYDRO PROJECT PLANNING & APPRAISAL) COMMERCIAL COMMITTEE MONITORING-II) APPRAISAL-II) CHIEF ENGINEER APPRAISAL) CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF ENGINEER (POWER DATA MS (NRPC) (DISTRIBUTION (HUMAN CHIEF ENGINEER CHIEF -

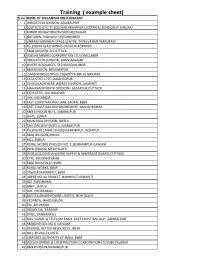

Training Example Sheet.Xlsx

Training ( example sheet) Sl no NAME OF ORGANISATION/COMPANY 1 IRRIGATION DIVISION ,SAMBALPUR 2 SOUTHCO UTILITY SOUTHBERHAMPUR ELECTRICAL DIVISION‐III GANJAM 3 MINOR IRRIGATION DIVISION,KEONJHAR 4 NATIONAL HIGHWAY DIVISION,BBSR 5 VIKRAM SARABHAI SPACE CENTRE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 6 TELENGIRI HEAD WORKS DIVISION KORAPUT 7 R&B( DIVISION ‐I),CUTTACK 8 ODISHA MINING CORPORATION LTD (OMC),BBSR 9 IRRIGATION DIVISION, BHANJANAGAR 10 WATER RESOURCES, SECHASADAN,BBSR 11 R&B DIVISION, BRAHMAPUR 12 GRASIM INDUSTRIES LTD(ADITYA BIRLA) GANJAM 13 TATA STEEL LTD , JAMSHEDPUR 14 CHHELIGADA HEAD WORKS DIVISION, GAJAPATI 15 MAHANADI NORTH DIVISION‐I JAGATPUR,CUTTACK 16 TATA STEEL, KALINGANAR 17 HAL, SUNABEDA 18 EAST COAST RAILWAY, RAIL SADAN, BBSR 19 EAST COAST RAILWAY(WORKSHOP) ,MANCHESWAR 20 R&B DIVISION NO‐1, SAMBALPUR 21 OHPC, BURLA 22 MAIN DAM DIVISION, BURLA 23 DIVL.RAILWAY (MECH) ,SAMBALPUR 24 TELENGIRI CANAL DIVISION,BANIRIPUT, KORAPUT 25 R&B) DIVISION,ANGUL 26 MCL, BURLA 27 RURAL WORKS DIVISION NO ‐1 ,BERHAMPUR GANJAM 28 PWD (ROADS) MEGHALAYA 29 OISIP,JICA,ODISHA WATER SUPPLY & SEWERAGE BOARD, CUTTACK 30 CTTC, BHUBANESWAR 31 R&B) DIVISION,JEYPORE 32 RURAL WORKS, BBSR 33 CPWD,POKHARIPUT, BBSR 34 UPPER KOLAB PROJECT, BANIRIPUT,KORAPUT 35 L&T ,KANSBAHAL 36 MNIT, JAIPUR 37 ECIL, HYDERABAD 38 BSES RAJDHANI POWER LIMITED, NEW DELHI 39 VEDANTA, JHARSUGUDA 40 TRL, BELPAHAR 41 INDIAN OIL, PARADIP 42 OPGC, BANHARPALI 43 DIVL SIGNAL & TELECOM ENGR. EAST COAST RAILWAY ,SAMBALPUR 44 R&B)DIVISION NO II, GANJAM 45 DESIGNS, WATER RESOURCES , BBSR 46 MCL, IB VALLEY -

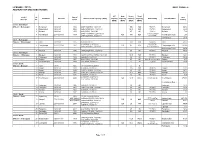

Grid Substation List

LICENSEE : OPTCL OERC FORM L-9 ABSTRACT OF GRID SUBSTATIONS ICT Auto Power Total Circle / Sl. Year of Grid S/S Name kV Level Details of S/S Capacity ( MVA) Capacity Capacity Capacity Capacity Grid Loading Grid Substation Division No. Comm. Loading (MVA) (MVA) (MVA) (MVA) Circle : Berhampur Division : Berhampur 1 Berhampur 132/33 kV 1964 2x40+1x20 MVA, 132/33 kV 100 100 55.38% Berhampur 52.61 2 Digapahandi 132/33 kV 2004 2x20+1x12.5 MVA, 132/33 kV 52.5 52.5 76.79% Digapahandi 38.30 3 Mohana 132/33 kV 1973 2x12.5 MVA, 132/33 kV 25 25 33.21% Mohana 7.89 2x160 +1x100MVA, 220/132 kV 37.36%(POWER) 4 Narendrapur 220/132/33 kV 1999 420 100 520 Narendrapur (Auto) 253 2x40+1x20 MVA, 132/33 kV 66%(AUTO) Narendrapur 39.93 Circle : Berhampur Division : Bhanjanagar 5 Aska 132/33 kV 1975 3x40, 132/33 kV 120 120 53.04% Aska 60.47 2x160 MVA, 220/132 kV 64%(AUTO) 6 Bhanjanagar 220/132/33 kV 1984 320 96 416 Bhanjanagar Auto 204.80 2x40+1x16 MVA, 132/33 kV 37.31%(POWER) Bhanjanagar Power 34.02 7 Phulbani 132/33 kV 1986 1x40+2x12.5 MVA, 132/33 kV 65 65 48.88% Phulbani 30.18 Circle : Berhampur Division : Chhatrapur 8 Balugaon 132/33 kV 1991 1x40+1x20+1x12.5 MVA, 132/33 kV 72.5 72.5 50.53% Balugaon 34.80 9 Chhatrapur 132/33 kV 1982 3x20 MVA, 132/33 kV 60 60 56.66% Chhatrapur 32.30 10 Ganjam 132/33 kV 1967 2x12.5 MVA, 132/33 kV 25 25 Major Renovation Work Ganjam 2.37 11 Purusottampur 132/33 kV 2013 2x12.5MVA, 132/33 kV 25 25 71.97% Purusottampur 17.09 Circle : Burla Division : Bolangir 12 ACME 132 kV 2015 132 kV Switching Station 0 0 13 Bargarh 132/33 kV 1979 -

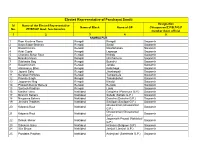

Elected Representative of Panchayat Samiti Designation Sl Name of the Elected Representative Name of Block Name of GP Chiarperson/Z.P/B.P/G.P No

Elected Representative of Panchayat Samiti Designation Sl Name of the Elected Representative Name of Block Name of GP Chiarperson/Z.P/B.P/G.P No. ZP/BP/GP Govt. functionaries member Govt. official 1 2 3 4 5 SAMBALPUR 1 Ram Krushna Rana Rengali Rengali Sarpanch 2 Daya Sagar Bhainsa Rengali Salad Sarpanch 3 Basanti Oram Rengali Nisanbhanga Sarpanch 4 Rubi Gupta Rengali Lapanga Sarpanch 5 Chandra Skhar Rout Rengali Khinda Sarpanch 6 Birendra Kisan Rengali Ghichamura Sarpanch 7 Subhadra Bag Rengali Bomaloi Sarpanch 8 Basanti Oram Rengali Jangla Sarpanch 9 Abhimanyu Bhoi Rengali Katarbaga Sarpanch 10 Jayanti Sahu Rengali Jhankarpali Sarpanch 11 Nurabati Rohidas Rengali Tamparkela Sarpanch 12 Pramila Singh Rengali Tabadabahal Sarpanch 13 Jagyansini Nag Rengali Kinaloi Sarpanch 14 Prakash Kumar Behera Rengali Rengloi Sarpanch 15 Santosh Pradhan Rengali Laida Sarpanch 16 Martha Lakra Naktideul Dangteka (Panimura G.P.) Sarpanch 17 Biranchi Behera Naktideul Sahebi (Sahebi G.P.) Sarpanch 18 Nirupama Behera Naktideul Daincha (Daincha G.P.) Sarpanch 19 Jitendra Pradhan Naktideul Similipal (Similipal G.P.) Sarpanch Ghusuramal (Ghusuramal 20 Kalpana Rout Naktideul Sarpanch G.P.) Ghusuramal (Ghusuramal 21 Kalpana Rout Naktideul Sarpanch G.P.) Jagannath Prasad (Naktideul 22 Debaki Meher Naktideul Sarpanch G.P.) 23 Dibakara Sahu Naktideul Hitasara (Batgaon G.P.) Sarpanch 24 Sita Biswal Naktideul Jamjori (Jamjori G.P.) Sarpanch 25 Pandaba Pradhan Naktideul Ambajhari (Salebhata G.P.) Sarpanch Elected Representative of Panchayat Samiti Designation Sl Name -

The Odisha G a Z E T T E

The Odisha G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 393 CUTTACK, MONDAY, MARCH 11, 2013/FALGUNA 20, 1934 ODISHA POWER TRANSMISSION CORPORATION LIMITED (A Government of Odisha Undertaking) OFFICE OF THE SENIOR GENERAL MANAGER (TRANSMISSION PROJECT & CONSTRUCTION) (GROUND & 1st FLOOR), TECHNICAL BUILDING, BHOI NAGAR, BHUBANESWAR - 751 022 Phone - 0674 - 2546353, Fax : 0674 - 2547261, e-mail : [email protected] NOTIFICATION The 9th October 2012 No. 3191—TP.-Estimate-Gazette-2004-Vol. VI.—In accordance with Section 164 of Indian Electricity Act, 2003 and in exercise of the power conferred upon OPTCL vide Department of Energy, Government of Odisha Order No. 2353—R&R-II-10/2006, dated the 9th March 2006, the following transmission schemes which Odisha Power Transmission Corporation Limited intends to undertake is published for general information. It is also notified in the interest of general public that any person interested in making representation regarding the execution of the above scheme, may submit such representation in writing so as to reach the Senior General Manager, Transmission Project & Construction, Odisha Power Transmission Corporation Limited, Technical Building, Ground & 1st Floor, Bhoi Nagar, Bhubaneswar - 751 022 within two months from the date of publication of this notification. Full details of the scheme and plan may be seen in the office of the concerned Assistant General Manager (Elect.) as mentioned against the work on any working day during office hours. Sl. Name of the Name of the villages Tentative Name of the Perceived No. work and scope in which the line estimated amount Executive Engineer benefit that will pass to be contacted may accrue (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 1 Construction of 3.077 Kms.