VRET Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

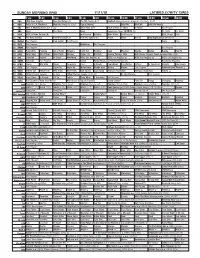

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

Photo Gallery

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL NOW ANY SHOW) ANY GOOD TOWARD AVAILABLE! ($25 INCREMENTS, Gift Certificates — Friday, May 11 - I Write the Songs Friday, A tribute to singing legend John Denver A Wednesday, Wednesday, Greatest Manilow hits from the ’70s & ’80s Aug. 16, 2017 16, Aug. (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS Sunday, Dec. 10 - A Rocky Mountain Christmas Sunday, Series Sponsor: Auditorium High School ALL SHOWS ALL 7:30 p.m. Northland Pines 2017-2018 For more information about tickets and shows A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A Weekdays 7 a.m.-4 p.m., Sat. 8 Sun. 9 a.m.-2 p.m. Weekdays or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, call Rick Roder at 920-676-3621. or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, presents: Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. Pine St. • Eagle River 715-479-7995 Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. The world-famous “Big Band” returns Featuring the lead guitarist from “Glee” Saturday, Nov. 4 - Derik Nelson & Family Nov. Saturday, Saturday, April 21 - Glenn Miller Orchestra Saturday, (2 ADULT & 2 CHILD) ADULT (2 FAMILY PKG. FAMILY 240/ $ • (17 & UNDER) OFF single ticket prices! OFF single ticket prices! NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL CHILDREN 45/ $ 2017-2018 CONCERT SEASON • 40% 40% SEASON TICKETS ON SALE NOW! “Duck Dynasty goes to Carnegie Hall” ADULTS Broadway favorites with a touch of Gospel 90/ Save Save $ Saturday, March 3 - Redneck Tenors Saturday, Friday, Sept.Friday, 8 - The Inspiration of Broadway © Eagle River Publications, Inc. -

Star Channels, July 5

JULY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com VAMP HUNTER Eight and a half years after the events of the Season 1 fi nale of NOS4A2, Charlie (Zachary Quinto) is at large, and Vic (Ashleigh Cummings) is still on his trail. The stakes have never been higher as Charlie targets Wayne (Jason David), the son of Vic and Lou (Jonathan Langdon). Airing Sunday, July 5, on AMC. COVID-19 UPDATES LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss the top issues facing our community, from their home to yours. olelo.org TUESDAY AT 8:30AM, WEDNESDAY AT 7PM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 590207_LiveAtTheLegislature_COVID-19_2_Main.indd 1 6/4/20 11:50 AM ON THE COVER | NOS4A2 Thirsty for more Season 2 of ‘NOS4A2’ for those big-screen adaptations. “NOS4A2,” Meanwhile, in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on the other hand, is perfect for the television a townie named Victoria “Vic” McQueen continues on AMC treatment. It’s been given a two-season-and- (Ashleigh Cummings, “The Goldfinch,” 2019) counting run on AMC, the network that’s been must come to terms with her own supernatu- By Rachel Jones home to mega-hits such as “Breaking Bad” and ral powers. She can find answers and missing TV Media “Mad Men.” things just by riding her bike across an old, The show’s title is ominously pronounced decrepit bridge called the Shorter Way. While he Season 1 finale of “NOS4A2” couldn’t “Nosferatu,” and its license plate-styled spell- crossing the bridge, Vic meets a medium have been more riveting: a maniacal im- ing is a nod to the book’s cover art and one of named Maggie (Jahkara Smith, “Into the Dark”), Tmortal woke up from his coma, ready to the story’s most important characters, a 1938 who gives her an important mission: save the feed on the souls of more children. -

The Hoosier Genealogist

INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY • SPRING/SUMMER 2008 • $5 THE HOOSIER GENEALOGIST IN THIS ISSUE: BIOGRAPHY OF A NAVAL CHAPLAIN FEDERAL COURT RECORDS CITY DIRECTORIES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Experience history in a whole new way… PRESENTED BY WITH SUPPORT FROM CLABBER GIRL Mr. Zwerner’s neighborhood Open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. grocery store is buzzing about Wednesdays through Saturdays events of the war. Step back in Free Admission time as costumed interpreters Eugene and Marilyn Glick share details of everyday Hoosier Indiana History Center 450 West Ohio Street life during World War II. Help Indianapolis, Indiana 46202-3269 run the store, fill orders and talk (800) 447-1830 about war-time events. www.indianahistory.org TM INDIANA’S STORYTELLER : CONNECTING PEOPLE TO THE PAST T H E H O O S I E R GENEALOGIST INDiaNA HisTORical SOciETY • SPRING/SUmmER 2008 • VOL. 48, ISSUE 1 Since 1830, the Indiana Historical Administration John A. Herbst • President and CEO Society has been Indiana’s Storyteller™, Stephen L. Cox • Executive Vice President Jeff Matsuoka • Vice President, Business and Operations connecting people to the past by col- Susan P. Brown • Vice President, Human Resources lecting, preserving, interpreting, and Linda Pratt • Vice President, Development and Membership Jeanne Scheets • Vice President, Marketing and Public Relations disseminating the state’s history. A non- Board of Trustees profit membership organization, the IHS Michael A. Blickman William Brent Eckhart also publishes books and periodicals; Chair Daniel M. Ent Thomas G. Hoback Richard D. Feldman, MD sponsors teacher workshops; provides First Vice Chair Richard E. Ford Sarah Evans Barker Wanda Y. -

Readings of Trauma and Madness in Hemingway, H.D., and Fitzgerald

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Readings of Trauma and Madness in Hemingway, H.D., and Fitzgerald Sarah Wood Anderson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved By: Linda Wagner-Martin Joseph Flora Minrose Gwin Fred Hobson William Harmon © 2010 Sarah Wood Anderson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Sarah Wood Anderson Readings of Trauma and Madness in Hemingway, H.D., and Fitzgerald (Under the direction of Linda Wagner-Martin) This project explores how Modernist fiction narratives represent trauma, considering first, the struggle (commonly identified in psychology literature) between the need to speak about one’s trauma and the equally powerful impulse to keep silent. Male representations of trauma differ noticeably from those of women, revealing social restrictions on both groups and offering an opportunity to explore the conditions under which characters both suffered trauma and retold it. Another, more overt and perhaps more common, indicator of trauma is madness. Furthering the debate between critics who read female madness as a resistance to patriarchy and those who read it as a site of further powerlessness, this examination presents a new category: that of the male representation of female insanity. This project presents instances of female insanity exacerbated by sexual and creative conflicts between men and women. iii To my children, who have been the most marvelous distractions To my husband, who always believed I could do this To my family: you are the rock upon which I do everything iv Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to thank those who have made this dissertation possible. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode). -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Super! Drama TV June 2021 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-6:00 on the 10Th

Super! drama TV June 2021 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-6:00 on the 10th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.05.31 2021.06.01 2021.06.02 2021.06.03 2021.06.04 2021.06.05 2021.06.06 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 06:00 00 00 00 00 06:00 00 00 06:00 STINGRAY #27 STINGRAY #29 STINGRAY #31 STINGRAY #33 STINGRAY #35 STINGRAY #37 『DEEP HEAT』 『TITAN GOES POP』 『TUNE OF DANGER』 『THE COOL CAVE MAN』 『TRAPPED IN THE DEPTHS』 『A CHRISTMAS TO REMEMBER』 06:30 30 30 30 30 06:30 30 30 06:30 STINGRAY #28 STINGRAY #30 STINGRAY #32 STINGRAY #34 STINGRAY #36 STINGRAY #38 『IN SEARCH OF THE TAJMANON』 『SET SAIL FOR ADVENTURE』 『RESCUE FROM THE SKIES』 『A NUT FOR MARINEVILLE』 『EASTERN ECLIPSE』 『THE LIGHTHOUSE DWELLERS』 07:00 00 00 00 00 07:00 00 00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #19 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #20 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #21 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #22 STAR TREK Season 1 #29 INSTINCT #5 『Tribute』 『Inner Beauty』 『Devil's Backbone』 『The Storm』 『Operation -- Annihilate!』 『Heartless』 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 00 00 00 00 08:00 00 00 08:00 MACGYVER Season 2 #12 MACGYVER Season 2 #13 MACGYVER Season 2 #14 MACGYVER Season 2 #15 MANHUNT: DEADLY GAMES #2 INSTINCT #6 『Mac + Jack』 『Co2 Sensor + Tree Branch』 『Mardi Gras Beads + Chair』 『Murdoc + Handcuffs』 『Unabubba』 『Flat Line』 08:30 08:30 08:30 09:00 00 00 00 00 09:00 00 00 09:00 information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] 09:30 30 30 30 30 09:30 30 30 09:30 ZOEY'S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST MANHUNT: -

Genre and Gender in Selected Works by Detection Club Writers Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie

SEVENTY YEARS OF SWEARING UPON ERIC THE SKULL: GENRE AND GENDER IN SELECTED WORKS BY DETECTION CLUB WRITERS DOROTHY L. SAYERS AND AGATHA CHRISTIE A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Monica L. Lott May 2013 Dissertation written by Monica L. Lott B.A., The University of Akron, 2003 B.S., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., The University of Akron, 2005 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Tammy Clewell Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Vera Camden Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Robert Trogdon Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Maryann DeJulio Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Clare Stacey Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by Robert Trogdon Chair, English Department Raymond A. Craig Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements.................................................................................... iv Introduction..................................................................................................1 Codification of the Genre.................................................................2 The Gendered Detective in Sayers and Christie ..............................9 Chapter Synopsis............................................................................11 Dorothy L. Sayers, the Great War, and Shell-shock..................................20 Sayers and World War Two in Britain ..........................................24 Shell-shock and Treatment