Readings of Trauma and Madness in Hemingway, H.D., and Fitzgerald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

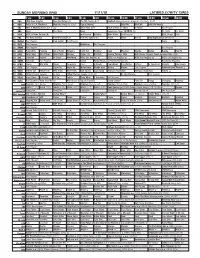

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

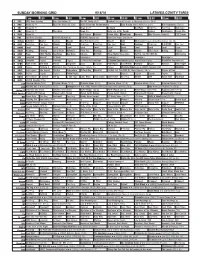

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

VRET Dissertation

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title War, Trauma, and Technologies of the Self : : The Making of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6698t67t Author Brandt, Marisa Renee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO War, Trauma, and Technologies of the Self: The Making of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication and Science Studies by Marisa Renee Brandt Committee in charge: Professor Chandra Mukerji, Chair Professor David Serlin Professor Kelly A. Gates Professor Charles Thorpe Professor Joseph Dumit 2013 Copyright Marisa Renee Brandt, 2013 All rights reserved SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Marisa Renee Brandt is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication in microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to all of the people around the world have suffered trauma as a result of the Global War on Terrorism. May we never give up on peace. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Dedication ........................................................................................................................... iv List -

Photo Gallery

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL NOW ANY SHOW) ANY GOOD TOWARD AVAILABLE! ($25 INCREMENTS, Gift Certificates — Friday, May 11 - I Write the Songs Friday, A tribute to singing legend John Denver A Wednesday, Wednesday, Greatest Manilow hits from the ’70s & ’80s Aug. 16, 2017 16, Aug. (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS Sunday, Dec. 10 - A Rocky Mountain Christmas Sunday, Series Sponsor: Auditorium High School ALL SHOWS ALL 7:30 p.m. Northland Pines 2017-2018 For more information about tickets and shows A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A Weekdays 7 a.m.-4 p.m., Sat. 8 Sun. 9 a.m.-2 p.m. Weekdays or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, call Rick Roder at 920-676-3621. or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, presents: Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. Pine St. • Eagle River 715-479-7995 Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. The world-famous “Big Band” returns Featuring the lead guitarist from “Glee” Saturday, Nov. 4 - Derik Nelson & Family Nov. Saturday, Saturday, April 21 - Glenn Miller Orchestra Saturday, (2 ADULT & 2 CHILD) ADULT (2 FAMILY PKG. FAMILY 240/ $ • (17 & UNDER) OFF single ticket prices! OFF single ticket prices! NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL CHILDREN 45/ $ 2017-2018 CONCERT SEASON • 40% 40% SEASON TICKETS ON SALE NOW! “Duck Dynasty goes to Carnegie Hall” ADULTS Broadway favorites with a touch of Gospel 90/ Save Save $ Saturday, March 3 - Redneck Tenors Saturday, Friday, Sept.Friday, 8 - The Inspiration of Broadway © Eagle River Publications, Inc. -

Star Channels, July 5

JULY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com VAMP HUNTER Eight and a half years after the events of the Season 1 fi nale of NOS4A2, Charlie (Zachary Quinto) is at large, and Vic (Ashleigh Cummings) is still on his trail. The stakes have never been higher as Charlie targets Wayne (Jason David), the son of Vic and Lou (Jonathan Langdon). Airing Sunday, July 5, on AMC. COVID-19 UPDATES LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss the top issues facing our community, from their home to yours. olelo.org TUESDAY AT 8:30AM, WEDNESDAY AT 7PM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 590207_LiveAtTheLegislature_COVID-19_2_Main.indd 1 6/4/20 11:50 AM ON THE COVER | NOS4A2 Thirsty for more Season 2 of ‘NOS4A2’ for those big-screen adaptations. “NOS4A2,” Meanwhile, in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on the other hand, is perfect for the television a townie named Victoria “Vic” McQueen continues on AMC treatment. It’s been given a two-season-and- (Ashleigh Cummings, “The Goldfinch,” 2019) counting run on AMC, the network that’s been must come to terms with her own supernatu- By Rachel Jones home to mega-hits such as “Breaking Bad” and ral powers. She can find answers and missing TV Media “Mad Men.” things just by riding her bike across an old, The show’s title is ominously pronounced decrepit bridge called the Shorter Way. While he Season 1 finale of “NOS4A2” couldn’t “Nosferatu,” and its license plate-styled spell- crossing the bridge, Vic meets a medium have been more riveting: a maniacal im- ing is a nod to the book’s cover art and one of named Maggie (Jahkara Smith, “Into the Dark”), Tmortal woke up from his coma, ready to the story’s most important characters, a 1938 who gives her an important mission: save the feed on the souls of more children. -

Daring Deceit

FINAL-1 Sun, Oct 25, 2015 11:52:55 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of November 1 - 7, 2015 Daring deceit Priyanka Chopra INSIDE stars in “Quantico” •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Hollywood Q&A Page 3 •Family Favorites Page 4 The plot thickens as Alex Parrish (Priyanka Chopra, “Fashion,” 2008) struggles to prove she wasn’t behind a terrorist attack in New York City in a new episode of “Quantico,” airing Sunday, Nov. 1, on ABC. Flashbacks recount Parrish’s time at the FBI academy, where she trained alongside a diverse group of recruits. As the flashbacks unfold, it becomes clear that no one is what they seem, and everyone has something to hide. RICHARD’S New, Used&Vintage FURNITURE 0% Reclining SALE *Sofas *Love Seats *Sectionals *Chairs NO INTEREST ON LOANS *15% off Custom Orders Only! Group Page Shell Richards 5 x 3” at 1 x 3” CASH FOR GOLD Ends Nov14th Remember TRADE INS arewelcome 527 S. Broadway,Salem, NH www.richardsfurniture.com (On the Methuen Line above Enterprise Rent-A-Car) 25 WaterStreet 603-898-2580 •OPEN 7DAYSAWEEK Lawrence,MA WWW.CASHFORGOLDINC.COM 978-686-3903 FINAL-1 Sun, Oct 25, 2015 11:52:56 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Countdown to Green Live NESN Bruins Face-Off Live Sunday 8:00 p.m. (25) Baseball MLB World (7) Salem Londonderry Series Live (25) College Football Pre-game Live 7:00 p.m. ESPN Football NCAA Live Windham 9:00 a.m. (25) Fox NFL Sunday Live Sandown ESPN Basketball NBA New York Knicks ESPN College Football Scoreboard NESN Hockey NHL Boston Bruins at Pelham, 9:30 a.m. -

The Hoosier Genealogist

INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY • SPRING/SUMMER 2008 • $5 THE HOOSIER GENEALOGIST IN THIS ISSUE: BIOGRAPHY OF A NAVAL CHAPLAIN FEDERAL COURT RECORDS CITY DIRECTORIES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Experience history in a whole new way… PRESENTED BY WITH SUPPORT FROM CLABBER GIRL Mr. Zwerner’s neighborhood Open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. grocery store is buzzing about Wednesdays through Saturdays events of the war. Step back in Free Admission time as costumed interpreters Eugene and Marilyn Glick share details of everyday Hoosier Indiana History Center 450 West Ohio Street life during World War II. Help Indianapolis, Indiana 46202-3269 run the store, fill orders and talk (800) 447-1830 about war-time events. www.indianahistory.org TM INDIANA’S STORYTELLER : CONNECTING PEOPLE TO THE PAST T H E H O O S I E R GENEALOGIST INDiaNA HisTORical SOciETY • SPRING/SUmmER 2008 • VOL. 48, ISSUE 1 Since 1830, the Indiana Historical Administration John A. Herbst • President and CEO Society has been Indiana’s Storyteller™, Stephen L. Cox • Executive Vice President Jeff Matsuoka • Vice President, Business and Operations connecting people to the past by col- Susan P. Brown • Vice President, Human Resources lecting, preserving, interpreting, and Linda Pratt • Vice President, Development and Membership Jeanne Scheets • Vice President, Marketing and Public Relations disseminating the state’s history. A non- Board of Trustees profit membership organization, the IHS Michael A. Blickman William Brent Eckhart also publishes books and periodicals; Chair Daniel M. Ent Thomas G. Hoback Richard D. Feldman, MD sponsors teacher workshops; provides First Vice Chair Richard E. Ford Sarah Evans Barker Wanda Y. -

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18, 2015 PAGE 11B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT DECEMBER 23, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Odd Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Nature Snowy owls NOVA “Building the Earthrise: Apollo 8 Vicious BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- A Crafts- NOVA “Building the PBS Squad Squad Kratts Å chase (In Speaks Business Stereo) Å on the North Slope of Great Cathedrals” and the First Lunar “Holiday World Stereo) Å ley Å man’s Great Cathedrals” KUSD ^ 8 ^ Stereo) Report Alaska. Gothic cathedrals. Voyage Å Special” News Legacy Gothic cathedrals. KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 ET Grinch Murray Adele-NYC Michael Bublé’s News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly Extra (N) Paid Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT Nightly KDLT The Big Dr. Seuss’ Murray- Adele Live in New Michael Bublé’s KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News News News Bang Grinch Xmas York City Adele per- Christmas in Holly- News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å (N) Å Theory forms in New York. wood Å (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode).