Grete Hermann, Quantum Mechanics, and the Evolution of Kantian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grete Hermann on Von Neumann's No-Hidden-Variables Proof

Challenging the gospel: Grete Hermann on von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof M.P Seevinck ∞ ∞ Radboud University University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands May 2012 1 Preliminary ∞ ∞ In 1932 John von Neumann had published in his celebrated book on the Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik, a proof of the impossibility of theories which, by using the so- called hidden variables, attempt to give a deterministic explana- tion of quantum mechanical behaviors. ◮ Von Neumann’s proof was sort of holy: ‘The truth, however, happens to be that for decades nobody spoke up against von Neumann’s arguments, and that his con- clusions were quoted by some as the gospel.’ (F. J. Belinfante, 1973) 2 ◮ In 1935 Grete Hermann challenged this gospel by criticizing the von Neumann proof on a fundamental point. This was however not widely known and her criticism had no impact whatsoever. ◮ 30 years later John Bell gave a similar critique, that did have great foundational impact. 3 Outline ∞ ∞ 1. Von Neumann’s 1932 no hidden variable proof 2. The reception of this proof + John Bell’s 1966 criticism 3. Grete Hermann’s critique (1935) on von Neu- mann’s argument 4. Comparison to Bell’s criticism 5. The reception of Hermann’s criticism 4 Von Neumann’s 1932 no hidden variable argument ∞ ∞ Von Neumann: What reasons can be given for the dispersion found in some quantum ensembles? (Case I): The individual systems differ in additional parameters, which are not known to us, whose values de- termine precise outcomes of measurements. = deterministic hidden variables ⇒ (Case II): ‘All individual systems are in the same state, but the laws of nature are not causal’. -

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief Der Gesellschaft Für Exilforschung E. V

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e. V. Nr. 53 ISSN 0946-1957 Juli 2019 Inhalt In eigener Sache In eigener Sache 1 Bericht Jahrestagung 2019 1 Später als gewohnt erscheint dieses Jahr der Doktoranden-Workshop 2019 6 Sommer-Nachrichtenbrief. Grund ist die Protokoll Mitgliederversammlung 8 diesjährige Jahrestagung, die im Juni AG Frauen im Exil 14 stattfand. Der Tagungsbericht und das Ehrenmitgliedschaft Judith Kerr 15 Protokoll der Mitgliederversammlung Laudatio 17 sollten aber in dieser Ausgabe erscheinen. Erinnerungen an Kurt Harald Der Tagungsbericht ist wiederum ein Isenstein 20 Gemeinschaftsprojekt, an dem sich diesmal Untersuchung Castrum Peregrini 21 nicht nur „altgediente“ GfE-Mitglieder Projekt „Gerettet“ 22 beteiligten, sondern dankenswerterweise CfP AG Frauen im Exil 24 auch zwei Doktorandinnen der Viadrina. CfP Society for Exile Studies 25 Ich hoffe, für alle, die nicht bei der Tagung Suchanzeigen 27 sein konnten, bieten Bericht und Protokoll Leserbriefe 27 genügend Informationen. Impressum 27 Katja B. Zaich Aus der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung Exil(e) und Widerstand Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung in Frankfurt an der Oder vom 20.-22. Juni 2019 Die Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft fand in diesem Jahr an einem sehr würdigen und dem Geiste der Veranstaltung kongenialen Ort statt, waren doch die Erbauer des Logenhauses in Frankfurt an der Oder die Mitglieder der 1776 gegründeten Freimaurerloge „Zum aufrichtigen Herzen“, die 1935 unter dem Zwang der Nazi-Diktatur ihre Tätigkeit einstellen musste und diese erst 1992 wieder aufnehmen konnte. Im Festsaal des Logenhauses versammelten sich am Donnerstagnachmittag Exilforscher/innen, Studierende und Gäste aus verschiedenen Ländern, darunter etwa 30 Mitglieder der Gesellschaft. Auf die Frage „Was ist die Freimaurerei?“ findet sich auf der Homepage der heute wieder dort arbeitenden Loge eine alte englische Definition, in der es unter anderem heißt: „gegen das Unrecht ist sie Widerstand“. -

In Der Spannung Pädagogik Und Politik Zum 100. Geburtstag

In der Spannung zwischen Naturwissenschaft, Pädagogik und Politik Zum 100. Geburtstag von Grete Henry-Hermann Herausgegeben von Susanne Miller und Helmut Müller ( im Auftrag der Philosophisch-Politischen Akademie e.V, Bonn r" In der Spannung zwischen Naturwissenschaft, Pädagogik und Politik ^ I m s» ^91 ^ ^ vy ^ S-. &ä m-: 9 M ^ s ?.-%'? m^.: fl^S ^ ft'f/ • A • . w^ ".;' fe ,, y. ->;t". Kv. jlti s. fö/ •.«•. frX'%i M^ S'f^f^ff .im s .1 Zum 100. Geburtstag von Crete Henry-Hermann ^^ 1S ^•^^•m ".* Zum 100. Geburtstag von Crete Hem'y-Hermann l Inhaltsverzeichnis Vonvort Dieter Krohn: Begrüßung Henning Scherf: Geleitwort des Präsidenten des Senats und Bürgermeisters der Freien Hansestadt Bremen Susanne Miller: Erinnerungen an Grete Henry-Hermann Lena Soler - Grete Henry-Hermanns Alexander Schnell: Beitrag zur Philosophie der Physik Ute Hönnecke: Der heilige Improvisatius — Grete Henry-Hermann als Leiterin der Lehrerausbildung in der Nachh-iegszeit Detlef Albers: Die Grundwerte im Mittelpunkt. Zur Aktualität des politischen Denkens von Grete Henry-Hermann Grete Henry-Hermann: Leonard Nelson und die Grundlagen des freiheitlichen Sozialismus Copyright: Philosophisch-Politische Akademie e. V, Bonn, 2001 Nachdruck nur mit Genehmigimg gestattet. Zum 100. Geburtstag von Crete Henry-Hermann Zum 100. Geburtstag von Crete Henry-Hermann Lena Soler und Alexander Schnell Crete Henry-Hermanns Beiträge zur Philosophie der Physik Wir werden uns deshalb im wesentlichen auf die Schrift von 1935 beschränken. Dieser Text wurde auf Betreiben von Lena Soler hin von Alexander Schnell übersetzt. Wir möchten Ihnen heute die grundlegenden Beiträge Grete Henry-Hermanns Dieses Buch ist 1996, mit einem einleitenden Vorwort und einem kritischen Nachwort zur Philosophie der Physik vorstellen. -

John Von Neumann's “Impossibility Proof” in a Historical Perspective’, Physis 32 (1995), Pp

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE Published: Louis Caruana, ‘John von Neumann's “Impossibility Proof” in a Historical Perspective’, Physis 32 (1995), pp. 109-124. JOHN VON NEUMANN'S ‘IMPOSSIBILITY PROOF’ IN A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ABSTRACT John von Neumann's proof that quantum mechanics is logically incompatible with hidden varibales has been the object of extensive study both by physicists and by historians. The latter have concentrated mainly on the way the proof was interpreted, accepted and rejected between 1932, when it was published, and 1966, when J.S. Bell published the first explicit identification of the mistake it involved. What is proposed in this paper is an investigation into the origins of the proof rather than the aftermath. In the first section, a brief overview of the his personal life and his proof is given to set the scene. There follows a discussion on the merits of using here the historical method employed elsewhere by Andrew Warwick. It will be argued that a study of the origins of von Neumann's proof shows how there is an interaction between the following factors: the broad issues within a specific culture, the learning process of the theoretical physicist concerned, and the conceptual techniques available. In our case, the ‘conceptual technology’ employed by von Neumann is identified as the method of axiomatisation. 1. INTRODUCTION A full biography of John von Neumann is not yet available. Moreover, it seems that there is a lack of extended historical work on the origin of his contributions to quantum mechanics. -

The Significance for Natural Philosophy of the Move From

Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2020) 51:627–629 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-020-09533-3 ARTICLE The Signifcance for Natural Philosophy of the Move from Classical to Modern Physics Grete Hermann1 Published online: 10 December 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 SUMMARY—This study shows how, despite the changes it has introduced, modern physics preserves certain fundamental ideas of classical physics (Bohr’s correspondence princi- ple). While it gives up much of the ideal of a mechanistic physics, it still remains tied to Kant’s thesis that the forms of intuition and the categories are the necessary presupposi- tions for the knowledge of nature. 1. The development of modern physics has two distinctive aspects: on the one hand the demand for a revision of almost all fundamental assumptions on which the knowledge of nature has been based until now, and indeed for a revision based on experience; on the other hand the upholding of certain fundamental conceptions of classical physics, which fnds its strongest expression in Bohr’s correspondence principle. Modern physics presents us with the problem within natural philosophy of reconciling these two aspects. 2. The dualism between the wave and particle picture in quantum mechanics, with its consequences for [our] causal command of natural phenomena represents the strongest departure from the classical picture of nature. But this departure is closely connected to a series of earlier transformations in the picture of nature. The frst step in this direction is taken in Maxwell’s theory, which detaches the wave picture from the presupposition of a material support until then taken for granted. -

Some Basic Biographical Facts About Emmy Noether (1882-1935), in Particular on the Discrimination Against Her As a Woman

Some basic biographical facts about Emmy Noether (1882-1935), in particular on the discrimination against her as a woman LMS-IMA Joint Meeting: Noether Celebration De Morgan House, Tuesday, 11 September, 2018 Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze (University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway) ABSTRACT Although it has been repeatedly underlined that Emmy Noether had to face threefold discrimination in political, racist and sexist respects the last- mentioned discrimination of the three is probably best documented. The talk provides some basic biographical facts about Emmy Noether with an emphasis on the discrimination against her as a woman, culminating for the first time in the struggles about her teaching permit (habilitation) 1915-1919 (main source C. Tollmien). Another focus of the talk will be on the later period of her life, in particular the failed appointment in Kiel (1928), her Born: 23 March 1882 in Erlangen, dismissal as a Jew in 1933 and her last years in the Bavaria, Germany U.S. Died: 14 April 1935 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, USA Older sources Obituaries by colleagues and students: van der Waerden, Hermann Weyl, P.S. Aleksandrov. Historians: Three women: Auguste Dick (1970, Engl.1981), Constance Reid (Hilbert 1970), and Cordula Tollmien (e.g. 1991 on Noether’s Habilitation); plus Norbert Schappacher (1987). Most material in German, Clark Kimberling (1972) in American Mathematical Monthly mostly translating from Dick and obituaries. Newer Sources Again mostly by women biographers, such as Renate Tobies (2003), Cordula Tollmien (2015), and Mechthild Koreuber (2015). The book below, of which the English version is from 2011, discusses the papers relevant for physics: After going through a girls school she took in 1900 a state exam to become a teacher in English and French at Bavarian girls schools. -

The Foundations of Quantum Mechanics in the Philosophy of Nature -- - by Grete Hermann Translated from the German, with an Introduction, by Dirk Lumma

The Foundations of Quantum Mechanics in the Philosophy of Nature -- - By Grete Hermann Translated from the German, with an Introduction, by Dirk Lumma HE FOLLOWING ARTICLE BY GRETE HERMANN ARGUABLY occupies an important place in the histo~yof the philosophical interpretation of quantum mechanics. The purpose of Hermann's writing on natural phi- losophy is to examine the revision of the law of causality which quantum Tmechanics seems to require at a fundamental level of theoretical description in physics. It is Hermann's declared intention to show that quantum mechanics does not disprove the concept of causaliv, 'fret has clarified [it] and has ~,enzovedfiomit other principles which are not necessarily connected to it."' She attempts to show that this most "obvi- ous" counter-example to the aprioricity of causality, quantztm theor?: is in fact not a counter-example at all. The central claim of Her~nan~z'sessay published in tbe 1930s' implies that quan- tzrm mechanics, "though predictively indeterministic, is retrodictive(y a causal theo~y."" In her argument, Herman11 commits to tbe orthodo.~fi)r~tz~tlntioiz(fquantum 1~2echan- ics characterized in Bohr's enr(?t essays': the quantrrm postulate, the iden that all obser- sntions "disturb" the object ~??rtenz,the fin mework of complcmentn ri~and tbc reqw irr- ment thnt the observing ageuc? be described by means of clnssicnl concepts. From today's point of view, Hermann's essays mtlst also be considered part of the debate about tbe completeness of the quantum mechanical description. For if she succccds, sbe will have rejected all those approaches as futile tvhieh aim to revise quantum theory on the basis of additional parameters in order to reinstate the predictabi1it-j~of specific experimental outcomes. -

„Um Etwas Zu Erreichen, Muss Man Sich Etwas Vornehmen, Von Dem Man Glaubt, Dass Es Unmöglich Sei“

Heiner Lindner „Um etwas zu erreichen, muss man sich etwas vornehmen, von dem man glaubt, dass es unmöglich sei“ Der Internationale Sozialistische Kampf-Bund (ISK) und seine Publikationen http://library.fes.de/isk Der Internationale Sozialistische Kampf-Bund (ISK) und seine Publikationen ISSN 0941-6862 ISBN 3-89892-450-5 muss man sich etwas vornehmen, „Um etwas zu erreichen, von dem man glaubt, dass es unmöglich sei“ FES Titel GK Gesch. 64 1 10.01.2006 8:25:58 Uhr Gesprächskreis Geschichte Heft 64 Heiner Lindner „Um etwas zu erreichen, muss man sich etwas vornehmen, von dem man glaubt, dass es unmöglich sei“ Der Internationale Sozialistische Kampf-Bund (ISK) und seine Publikationen „Zugleich Einleitung zur Internetausgabe der Zeitschrift „Renaissance“ Juli bis Oktober 1941 sowie der Pressekorrespondenzen “Germany speaks” und “Europe speaks” 1940, 1942 bis 1947 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Historisches Forschungszentrum Herausgegeben von Dieter Dowe Historisches Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Kostenloser Bezug beim Historischen Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Godesberger Allee 149, D-53175 Bonn Tel.: 0228 – 883-473 E-mail: [email protected] © 2006 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn (-Bad Godesberg) Umschlag: Pellens Kommunikationsdesign GmbH, Bonn, unter Verwendung der von Bernd Raschke, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, entworfenen Auftaktseite für die Online-Edition der Zeitschrift „Re- naissance“ sowie der Pressekorrespondenzen „Germany speaks“ und „Europe speaks“ Herstellung: Katja Ulanowski, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Druck: bub Bonner Universitäts-Buchdruckerei Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2006 ISSN 0941-6862 ISBN 3-89892-450-5 3 Vorwort Die Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung stellt in diesen Tagen die ungekürz- te Online-Ausgabe der Zeitschrift „Renaissance“ ins Netz, jenes Periodikums also, das der Internationale Sozialistische Kampf- Bund (ISK) unter der Herausgeberschaft Willi Eichlers 1941 im Londoner Exil veröffentlichte. -

Bohr's Complementarity and Kant's Epistemology

Bohr, 1913-2013, S´eminairePoincar´eXVII (2013) 145 { 166 S´eminairePoincar´e Bohr's Complementarity and Kant's Epistemology Michel Bitbol Archives Husserl ENS - CNRS 45, rue d'Ulm 75005 Paris, France Stefano Osnaghi ICI - Berlin Christinenstraße 18-19 10119, Berlin, Germany Abstract. We point out and analyze some striking analogies between Kant's transcendental method in philosophy and Bohr's approach of the fundamental issues raised by quantum mechanics. We argue in particular that some of the most controversial aspects of Bohr's views, as well as the philosophical concerns that led him to endorse such views, can naturally be understood along the lines of Kant's celebrated `Copernican' revolution in epistemology. 1 Introduction Contrary to received wisdom, Bohr's views on quantum mechanics did not gain uni- versal acceptance among physicists, even during the heyday of the so-called `Copen- hagen interpretation' (spanning approximately between 1927 and 1952). The `ortho- dox' approach, generally referred to as `the Copenhagen interpretation', was in fact a mixture of elements borrowed from Heisenberg, Dirac, and von Neumann, with a few words quoted from Bohr and due reverence for his pioneering work, but with no unconditional allegiance to his ideas [Howard2004][Camilleri2009]. Bohr's physical insight was, of course, never overtly put into question. Yet many of his colleagues found his reflections about the epistemological status of theoretical schemes, as well as his considerations on the limits of the representations employed by science, ob- scure and of little practical moment { in a word: too philosophical.1 In addition, it proved somehow uneasy to reach definite conclusions as to the true nature of this philosophy. -

Translation of Three Short Papers by Grete Hermann

Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2020) 51:615–619 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-020-09530-6 ARTICLE Translation of Three Short Papers by Grete Hermann Guido Bacciagaluppi1 Published online: 27 November 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 After a number of years of relative neglect, it is now becoming apparent that Grete Her- mann (1901–1984) was one of the most accomplished neo-Kantian philosophers of the last century—in part thanks to the recent publication of two volumes on and of her work, one in English (Crull and Bacciagaluppi 2017) and one in German (Herrmann 2019), both reviewed in this issue. The latter in particular contains Hermann’s entire output on modern physics and philosophy of science. Below I translate the three shortest papers by Hermann in that volume, which I intro- duce here. They provide quick but fascinating glimpses into some of Hermann’s ideas on philosophy of science, quantum mechanics and transcendental idealism. They are: from 1935 a book review of Popper’s Logik der Forschung (the original German edition of The Logic of Scientifc Discovery), from 1936 a comment on Schlick’s posthumously published talk ‘Quantentheorie und Erkennbarkeit der Natur’ (‘Quantum Theory and Knowability of Nature’) and from 1937 a short summary of Hermann’s ideas on the relation between Kant’s philosophy and modern physics (specifcally electrodynamics, the special and gen- eral theories of relativity and quantum mechanics) presented at the Congrès Descartes in Paris.1 1 Popper Review Popper had published Logik der Forschung in late 1934 (with the impressum of the fol- lowing year, Popper 1935). -

![Arxiv:2003.03554V3 [Math-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6807/arxiv-2003-03554v3-math-ph-2016807.webp)

Arxiv:2003.03554V3 [Math-Ph]

Indeterminism and Undecidability Klaas Landsman Department of Mathematics, Institute for Mathematics, Astrophysics, and Particle Physics (IMAPP), Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Dedicated to the memory of Michael Redhead (1929–2020) Abstract The aim of this paper is to argue that the (alleged) indeterminism of quantum me- chanics, claimed by adherents of the Copenhagen interpretation since Born (1926), can be proved from Chaitin’s follow-up to G¨odel’s (first) incompleteness theorem. In comparison, Bell’s (1964) theorem as well as the so-called free will theorem–originally due to Heywood and Redhead (1983)–left two loopholes for deterministic hidden vari- able theories, namely giving up either locality (more precisely: local contextuality, as in Bohmian mechanics) or free choice (i.e. uncorrelated measurement settings, as in ’t Hooft’s cellular automaton interpretation of quantum mechanics). The main point is that Bell and others did not exploit the full empirical content of quantum mechanics, which consists of long series of outcomes of repeated measurements (idealized as in- finite binary sequences): their arguments only used the long-run relative frequencies derived from such series, and hence merely asked hidden variable theories to repro- duce single-case Born probabilities defined by certain entangled bipartite states. If we idealize binary outcome strings of a fair quantum coin flip as infinite sequences, quantum mechanics predicts that these typically (i.e. almost surely) have a property called 1-randomness in logic, which is much stronger than uncomputability. This is the key to my claim, which is admittedly based on a stronger (yet compelling) notion of determinism than what is common in the literature on hidden variable theories. -

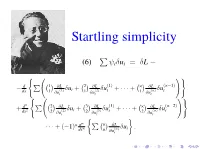

Startling Simplicity

Startling simplicity P (6) iδui = δL − ( !) d P 1 @L 2 @L (1) k @L (k−1) − dx 1 (1) δui + 1 (2) δui + ··· + 1 (k) δui @ui @ui @ui ( !) d2 P 2 @L 3 @L (1) k @L (k−2) + dx2 2 (2) δui + 2 (3) δui + ··· + 2 (k) δui @ui @ui @ui k dk P k @L ··· + (−1) dxk k (k) δui : @ui On its face, an equation Euler or Lagrange could have written. Direct consequence of additivity, chain rule, and integration by parts. In several independent variables those lines become a sum: @A @A Div(A) = 1 + ··· + n : @x1 @xn Noether’s Aj are not functions. They are differential operators. d The last three lines are a derivative dx . Direct consequence of additivity, chain rule, and integration by parts. In several independent variables those lines become a sum: @A @A Div(A) = 1 + ··· + n : @x1 @xn Noether’s Aj are not functions. They are differential operators. d The last three lines are a derivative dx . On its face, an equation Euler or Lagrange could have written. In several independent variables those lines become a sum: @A @A Div(A) = 1 + ··· + n : @x1 @xn Noether’s Aj are not functions. They are differential operators. d The last three lines are a derivative dx . On its face, an equation Euler or Lagrange could have written. Direct consequence of additivity, chain rule, and integration by parts. Noether’s Aj are not functions. They are differential operators. d The last three lines are a derivative dx . On its face, an equation Euler or Lagrange could have written.