Cash-For-Shelter Pilot Findings in CRS's Typhoon Haiyan Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (As of 24 Mar)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (as of 24 Mar) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_REHAB_24032014_v1 BIRI PALAPAG LAVEZARES SAN JOSE ALLEN ROSARIO BOBON MONDRAGON LAOANG VICTORIA SAN CATARMAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL SAN CATUBIG ANTONIO PAMBUJAN GAMAY N O R T H E R N S A M A R LAPINIG SAN SAN ISIDRO VICENTE LOPE DE VEGA LAS NAVAS SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE SAN POLICARPIO CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO MASLOG ORAS SANTA GANDARA TAGAPUL-AN MARGARITA DOLORES SAN JOSE DE BUAN SAN JORGE CAN-AVID PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO TARANGNAN SANTO PARANAS NI-O (WRIGHT) TAFT CITY OF JIABONG CATBALOGAN SULAT MARIPIPI W E S T E R N S A M A R B I L I R A N SAN JULIAN KAWAYAN SAN SEBASTIAN ZUMARRAGA HINABANGAN CULABA ALMERIA CALBIGA E A S T E R N S A M A R NAVAL DARAM CITY OF BORONGAN CAIBIRAN PINABACDAO BILIRAN TALALORA VILLAREAL CALUBIAN CABUCGAYAN SANTA RITA BALANGKAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BABATNGON ISIDRO BASEY BARUGO LLORENTE LEYTE SAN HERNANI TABANGO MIGUEL CAPOOCAN ALANGALANG MARABUT BALANGIGA TACLOBAN GENERAL TUNGA VILLABA CITY MACARTHUR CARIGARA SALCEDO SANTA LAWAAN QUINAPONDAN MATAG-OB KANANGA JARO FE PALO TANAUAN PASTRANA ORMOC CITY GIPORLOS PALOMPON MERCEDES DAGAMI TABONTABON JULITA TOLOSA GUIUAN ISABEL MERIDA BURAUEN DULAG ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA L E Y T E MACARTHUR JAVIER (BUGHO) CITY OF BAYBAY ABUYOG MAHAPLAG INOPACAN SILAGO HINDANG SOGOD Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN BATO per Municipality SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary MATALOM SAN JUAN TOMAS (CABALIAN) OPPUS Municipality boundary MALITBOG S O U T H E R N L E Y T E Ongoing rehabilitation Ongoing MAASIN CITY activites LILOAN MACROHON PADRE BURGOS SAN 1-30 Planned FRANCISCO SAN 30-60 RICARDO LIMASAWA PINTUYAN 60-90 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters 0 325 K650 975 1,300 1,625 90-121 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES AS OF 24th Mar 2014 Early Food Sec. -

SHELTER CLUSTER GUIUAN Shelter Cluster Meeting Minutes/Updates

SHELTER CLUSTER GUIUAN Shelter Cluster Meeting Minutes/Updates Document approved by Shelter Cluster Partners in Guiuan Monday 2nd December 2013 8am Update is followed by notes from the meeting – discussion points in outline form List of cluster members in attendance: ACTED, ICRC, IOM, Habitat for Humanity (HFH), Catholic Relief Services (CRS), SOS Attitude, People in Need, UNHCR, WASH/EDUC Cluster (UNICEF), OCHA Please note: Due to the high number of bi-laterals and inability for all partners to meet daily or twice a week after the OSOCC general meeting at 6pm, the Shelter Cluster has determined it necessary to reform the meeting process. From now on, we will meet weekly on Mondays at 8:00 am at the UN OSOCC compound. Logistics will begin meeting directly after Shelter in an effort to support the logistics involved with Shelter cluster partner plans determined during the weekly meeting. CCCM partners will be invited as well. Coordination: Due to the large growth in partners, we encourage all to make time for the Monday meetings, and we encourage all partners to email or write down all 3Ws information needed for the global cluster so that we can support national and local coordination. It is very important that cluster partners send 3W information to [email protected] of IFRC in TAC, and cc [email protected] in Guiuan as well as the UNDAC email in Guiuan to assure that documents get to all pertinent actors. Terminology/Definitions: 1. Guiuan Operating Area (GOA) = Eastern Samar North to Balankaya and West to Lawaan, and including Marabut 2. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Situation Report No. 9 (as of 15 November 2013) This report is produced by OCHA Philippines in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHA Philippines. It covers the period from 14 to 15 November 2013. The report is issued at 18:00 Manila time (10:00 UTC). The next report will be issued on or around 16 November. Highlights The number of people affected has increased to 12.9 million, with over 1.9 million people displaced. This represents a significant increase from the previous reporting period. An estimated 150,000 people have access to water from 28,000 water connections which have been restored in eight municipalities in Tacloban. 170,475 people received family food packs, of which over 34,000 packs were distributed on 14 November in Leyte. 12.9 million 1.9 million 285,993 Affected people People displaced Damaged houses Source: DSWD as at 18:00 (10:00 UTC) Situation Overview One week after Typhoon Haiyan (locally known as Yolanda) struck the Philippines, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) estimates that 12.9 million people have been affected across nine regions (Eastern Visayas, Western Visayas, Central Visayas, MIMAROPA, CALABARZON, Bicol, Northern Mindanao, Davao, and Caraga). These figures continue to change as more reports are verified. The number of people displaced increased from 900,000 people on 14 November to 1.9 million people on 15 November. In the same period, the number of people living outside of evacuation centers has almost tripled from over 575,000 people to 1.4 million people. -

Philippine Crocodile Crocodylus Mindorensis Merlijn Van Weerd

Philippine Crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis Merlijn van Weerd Centre of Environmental Science, Leiden University, Abel Tasmanstraat 5bis, Utrecht 3531 GR, Netherlands ([email protected]) Common Names: Philippine crocodile (English), buwaya 2009 IUCN Red List: CR (Critically Endangered. Criteria (general Philippines), bukarot (northern Luzon) A1c. Observed decline in extent of occurrence >80% in 3 generations. C2a. Less than 250 adults in the wild, populations highly fragmented and declining; IUCN 2009) (last assessed Range: Philippines in 1996). Taxonomic Status The Philippine crocodile was described in 1935 by Karl Schmidt on the basis of a type specimen and three paratypes from the island of Mindoro (Schmidt 1935, 1938). Schmidt also described the closely related New Guinea freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus novaeguineae) in 1928 and later made a comparison of morphological differences between C. mindorensis, C. novaeguineae and C. porosus, maintaining C. mindorensis as a separate species (1956). However the Philippine crocodile has long been treated as C. novaeguineae mindorensis, a sub-species of the New Guinea crocodile, by other authorities. Hall (1989) provided new evidence of the distinctness of the Philippine crocodile and nowadays C. mindorensis is generally treated as a full species endemic to the Philippines. Figure 1. Distribution of Crocodylus mindorensis. Figure 2. Juvenile C. mindorensis in Dunoy Lake, in Northern Sierra Madre National Park, northern Luzon. Photograph: Merlijn van Weerd. Conservation Overview CITES: Appendix I Ecology and Natural History CSG Action Plan: The Philippine crocodile is a relatively small freshwater Availability of recent survey data: Adequate crocodile. Although much is still unknown, studies at two Need for wild population recovery: Highest captive breeding facilities [Palawan Wildlife Rescue and Potential for sustainable management: Low Conservation Centre (PWRCC), Palawan Island (Ortega Van Weerd, M. -

The Mangrove Forests Change and Impacts from Tropical Cyclones in the Philippines Using Time Series Satellite Imagery

remote sensing Article The Mangrove Forests Change and Impacts from Tropical Cyclones in the Philippines Using Time Series Satellite Imagery Mary Joy C. Buitre 1,2, Hongsheng Zhang 1,3,* and Hui Lin 4 1 Institute of Space and Earth Information Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T. 999077, Hong Kong; [email protected] 2 Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development (PCIEERD), DOST Compound, Taguig 1631, Philippines 3 Shenzhen Research Institute, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen 518057, China 4 School of Geography and Environment, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang 330022, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-3943-4195 Received: 3 February 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2019; Published: 22 March 2019 Abstract: The Philippines is rich in mangrove forests, containing 50% of the total mangrove species of the world. However, the vast mangrove areas of the country have declined to about half of its cover in the past century. In the 1970s, action was taken to protect the remaining mangrove forests under a government initiative, recognizing the ecological benefits mangrove forests can bring. Here, we examine two mangrove areas in the Philippines—Coron in Palawan and Balangiga-Lawaan in Eastern Samar over a 30-year period. Sets of Landsat images from 1987 to 2016 were classified and spatially analyzed using four landscape metrics. Additional analyses of the mangrove areas’ spatiotemporal dynamics were conducted. The impact of typhoon landfall on the mangrove areas was also analyzed in a qualitative manner. Spatiotemporal changes indicate that both the Coron and Balangiga-Lawaan mangrove forests, though declared as protected areas, are still suffering from mangrove area loss. -

Information Bulletin Philippines: Typhoon Ambo (Vongfong)

Information bulletin Philippines: Typhoon Ambo (Vongfong) Glide n° TC-2020-000134-PHL Date of issue: 14 May 2020 Date of disaster Expected landfall on 14 May 2020 Point of contact: Leonardo Ebajo, PRC Disaster Management Services Operation start date: N/A Expected timeframe: N/A Category of disaster: N/A Host National Society: Philippine Red Cross (PRC) Number of people affected: 7.1 million exposed Number of people to be assisted: N/A N° of National Societies currently involved in the operation: N/A N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: N/A This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. The Philippine Red Cross (PRC), with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is not seeking funding or other assistance from donors for this operation at this time. However, this might change as the situation evolves, especially after the storm makes landfall. An imminent DREF activation is currently under consideration. <click here to view the map of the affected area, and click here for detailed contact information> The situation According to the Philippines Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) as of 04:00 hours local time on 14 May 2020, Typhoon Vongfong is approximately 230 kilometers east of the Catarman, Northern Samar, moving west at 15 kmph. On entering the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR), it has been locally named “Typhoon Ambo”. PAGASA reports that Typhoon Ambo has maximum sustained winds of 150 kmph near the center and gustiness of up to 185 kmph. -

Notes on Current Health and Health

Addendum : Notes on current health and health –related programs in the Philippines – Implications on the Reproductive Roles of Indgenous Women (c2-24-16) -- The government’s allocation for health is now the highest for 2016. However the failure to achieve the MDGs 4 and 5 is attributed to the basic lack of accountaBility of the government to invest in the long-term Benefit of the poor Filipinos through provision of Basic necessities to facilitate effective health delivery to Filipinos, especially to the marginalized sector. According to Folger (2015), in her article for aspiring expats to the Philippines: “In the Philippines, the reports notes, the level of per-person healthcare spending is one of the lowest among Southeast Asia’s major economies. At 4.6%, the same holds true for spending as a proportion of GDP. Due to weak public financing, that number is expected to drop to 4.5% by 2018. At the same time, the nation’s healthcare spending is projected to increase an average of 8% annually, from an estimated $12.5 billion in 2013 to $20 billion in 2018. To address the growing need for improved healthcare coverage, the government in 2013 passed the Universal Healthcare Bill, which promises health insurance for all Philippine nationals, especially the poor”. Still prevalent up to now is shortage of medical personnel in the Philippines, in general, more so in rural areas. According to Folger (2015): “Another challenge facing many countries in Southeast Asia is the chronic shortage of medical personnel. The average number of physicians in Southeast Asia is 0.6 per 1,000 people; in the Philippines, that figure is slightly higher at approximately one physician per 1,000 Filipinos. -

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 Provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020 Key Highlights Summary of Classification Conclusions Summary of Underlying and Limiting Factors Out of the 71 provinces Severe chronic food insecurity (IPC Major factors limiting people from being food analyzed, Lanao del Sur, level 4) is driven by poor food secure are the poor utilization of food in 33 Sulu, Northern Samar consumption quality, quantity and provinces and the access to food in 23 provinces. and Occidental Mindoro high level of chronic undernutrition. Unsustainable livelihood strategies are major are experiencing severe In provinces at IPC level 3, quality of drivers of food insecurity in 32 provinces followed chronic food insecurity food consumption is worse than by recurrent risks in 16 provinces and lack of (IPC Level 4); 48 quantity; and chronic undernutrition financial capital in 17 provinces. provinces are facing is also a major problem. In the provinces at IPC level 3 and 4, the majority moderate chronic food The most chronic food insecure of the population is engaged in unsustainable insecurity (IPC Level 3), people tend to be the landless poor livelihood strategies and vulnerable to seasonal and 19 provinces are households, indigenous people, employment and inadequate income. affected by a mild population engaged in unsustainable Low-value livelihood strategies and high chronic food insecurity livelihood strategies such as farmers, underemployment rate result in high poverty (IPC Level 2). unskilled laborers, forestry workers, incidence particularly in Sulu, Lanao del Sur, Around 64% of the total fishermen etc. that provide Maguindanao, Sarangani, Bukidnon, Zamboanga population is chronically inadequate and often unpredictable del Norte (Mindanao), Northern Samar, Samar food insecure, of which income. -

Understanding Community Preferences for the Use and Management of Samar Island Forest Reserve Based on Participatory Rural Appraisap

UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY PREFERENCES FOR THE USE AND MANAGEMENT OF SAMAR ISLAND FOREST RESERVE BASED ON PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAP ..'-- USAIO ******* ...-- UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY PREFERENCES FOR THE USE AND MANAGEMENT OF SAMAR ISLAND FOREST RESERVE BASED ON PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAL 1 by LUIS P. ELEAZAR2 Institutional! PRA SpE'cialist July 2000 • Samar Island Biodiversity Study (SAMBIO) Resources, Environment and Economics Center for Studies, Inc. (REECS) In association wiTh Tandaya Foundation Eastern Samar Development Foundation, Inc. (ESADEF) Samar Center for Rural Education and Development, Inc. (SACRED) .. I Thi .. publication was made- possible through support provided by Ihe> lJ. S. AgE"ncy for International DE"velopmpnl fl!5AIDl under the INms of Gr.ant No. 492-G-Oo-OO-00001-00. ThE' opinions expressed hNein are those- of the dulnor dod drJ nol npl.f-':-:-arily fenecllhe views of the U. S. Agency for Internalional DE'v€'iopment. Th~-" .\lIlhor. Mr. luis P. Ele..lzar, is the PRA SpE'cialist of SAMBIO, REECS . ... TABLE OF CONTENTS list of Tables list of Figures Executive Summary...........•...........••.•..•.••..•...•........•..•.•..•.•.•....••••.........•.•.....•.•. vi 1. INTRODUCTION...............................................................•..•............•.. 1 .. 1.1 PRA in the Context of SAMBIO . 1 1.2 The PRA Objectives . 2 1.3 The PRA Teams . 2 ... 2. EXPLANATORY NOTES ON PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAiSAL.......•• 3 2.1 Why PRA? . 3 2.2 PRA Research Plan . 3 2.3 PRA Sites and Participants . 4 2.4 Methodology of PRA . 6 3. GENERAL CONTEXT OF SAMAR ISLAND...•..••••..•••••...•••.•....•..•.....•.••.•.•• 8 3.1 Background Information . 8 3.2 Land Use . 9 3.3 Local Economy . 11 3.3.1 Agriculture . 13 3.3.2 Cottage Industry . 14 3.3.3 Tourism . -

Region 8 Households Under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950

Philippines: Region 8 Households under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950 Lavezares Laoang Palapag Allen 2174 Rosario San Jose 5259 2271 1519 811 1330 San Roque Pambujan Mapanas Victoria Capul 1459 1407 960 1029 Bobon Catarman 909 San Antonio Mondragon Catubig 1946 5978 630 2533 1828 Gamay San Isidro Northern Samar 2112 2308 Lapinig Lope de Vega Las Navas Silvino Lobos 2555 Jipapad 602 San Vicente 844 778 595 992 Arteche 1374 San Policarpo Matuguinao 1135 Calbayog City 853 Oras 11265 2594 Maslog Calbayog Gandara Dolores ! 2804 470 Tagapul-An Santa Margarita San Jose de Buan 2822 729 1934 724 Pagsanghan San Jorge Can-Avid 673 1350 1367 Almagro Tarangnan 788 Santo Nino 2224 1162 Motiong Paranas Taft 1252 2022 Catbalogan City Jiabong 1150 4822 1250 Sulat Maripipi Samar 876 283 San Julian Hinabangan 807 Kawayan San Sebastian 975 822 Culaba 660 659 Zumarraga Almeria Daram 1624 Eastern Samar 486 Biliran 3934 Calbiga Borongan City Naval Caibiran 1639 2790 1821 1056 Villareal Pinabacdao Biliran Cabucgayan Talalora 2454 1433 Calubian 588 951 746 2269 Santa Rita Maydolong 3070 784 Basey Balangkayan Babatngon 3858 617 1923 Leyte Llorente San Miguel Hernani Tabango 3158 Barugo 1411 1542 595 2404 1905 Tacloban City! General Macarthur Capoocan Tunga 7531 Carigara 1056 2476 367 2966 Alangalang Marabut Lawaan Balangiga Villaba 3668 Santa Fe Quinapondan 1508 1271 800 895 2718 Kananga Jaro 997 Salcedo 2987 2548 Palo 1299 Pastrana Giporlos Matag-Ob 2723 1511 902 1180 Leyte Tanauan Mercedes Ormoc City Dagami 2777 326 Palompon 6942 2184 Tolosa 1984 931 Julita Burauen 1091 -

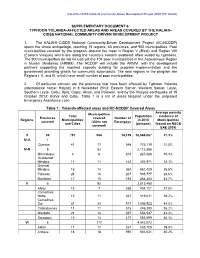

Supplementary Document 6: Typhoon Yolanda-Affected Areas and Areas Covered by the Kalahi– Cidss National Community-Driven Development Project

KALAHI–CIDSS National Community-Driven Development Project (RRP PHI 46420) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT 6: TYPHOON YOLANDA-AFFECTED AREAS AND AREAS COVERED BY THE KALAHI– CIDSS NATIONAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 1. The KALAHI–CIDDS National Community-Driven Development Project (KC-NCDDP) spans the whole archipelago, reaching 15 regions, 63 provinces, and 900 municipalities. Poor municipalities covered by the program abound the most in Region V (Bicol) and Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) which are along the country’s eastern seaboard often visited by typhoons. The 900 municipalities do not include yet the 104 poor municipalities in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The NCDDP will include the ARMM, with the development partners supporting the required capacity building for program implementation and the government providing grants for community subprojects. The new regions in the program are Regions I, II, and III, which have small number of poor municipalities. 2. Of particular concern are the provinces that have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 8 November 2013: Eastern Samar, Western Samar, Leyte, Southern Leyte, Cebu, Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Palawan, and by the Visayas earthquake of 15 October 2013: Bohol and Cebu. Table 1 is a list of areas targeted under the proposed Emergency Assistance Loan. Table 1: Yolanda-affected areas and KC-NCDDP Covered Areas Average poverty Municipalities Total Population incidence of Provinces covered Number of Regions Municipalities in 2010 Municipalities -

Northern Samar

NORTHERN SAMAR DISSEMINATION FORUM October 3, 2019, Ciriaco Hotel & Resort, Calbayog City 2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey METHODOLOGY Old Survey Design of the NNS Features Description Survey Design One shot (one year) every 5 years Coverage 17 regions, 81 provinces National, Regional, Level of Disaggregation Provincial for some indicators Target Number of Households 60,000 Households and all members of the sampled Target Population households Duration of Data Collection 6.5 Months (one shot) for the reference year Why did we change the design of the NNS? . Provide Province and HUC Level estimates for local planning of specific and sensitive interventions of our stakeholders . Provide reliable National Level Estimates annually Why did we change the design of the NNS? . Adoption of the new Master Sample of the PSA to provide reliable estimations at the Province and HUC Levels Sampling Design of the 2018 ENNS 2013 Master Sample (PSA) Sampling domains: 2-Stage Cluster Sampling Design 81 provinces st 33 HUCs 1 Stage - PSUs 3 other areas PSU size ranges from (Pateros, Isabela City, Cotabato City) 100 to 400 households z 16 sample replicates are drawn from each domain 2nd stage Households from 16 replicates (1,536) Icons used were retrieved from http://www.flaticon.com PSA Board Resolution No. 06 Approving and Adopting the Survey Design of the Expanded National Nutrition Survey What is the Survey Design of the 2018 NNS? 40 Provinces & ROLLING HUCs for 2018 40 Provinces & for HUCs for 2019 SURVEY 37 Provinces & 3YEARS HUCs for 2020 Target coverage per sampling domain is 1,536 households Survey Design of ENNS – a “Rolling Survey” NNS COMPONENTS 1.