Yinka O Lom Ojobi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa? DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS BUT NO DEMOCRACY Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos cahiers & conférences travaux & recherches les études The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non- profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. The Sub-Saharian Africa Program is supported by: Translated by: Henry Kenrick, in collaboration with the author © Droits exclusivement réservés – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-709-8 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – France 1000 Bruxelles – Belgique Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet Website : Ifri.org Summary Sub-Saharan African hopes of democratization raised by the end of the Cold War and the decline in the number of single party states are giving way to disillusionment. -

Preliminary Pages

! ! UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ! RIVERSIDE! ! ! ! ! Tiny Revolutions: ! Lessons From a Marriage, a Funeral,! and a Trip Around the World! ! ! ! A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction ! of the requirements! for the degree of ! ! Master of !Fine Arts ! in!! Creative Writing ! and Writing for the! Performing Arts! by!! Margaret! Downs! ! June !2014! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Thesis Committee: ! ! Professor Emily Rapp, Co-Chairperson! ! Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson! ! Professor David L. Ulin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright by ! Margaret Downs! 2014! ! ! The Thesis of Margaret Downs is approved:! ! !!_____________________________________________________! !!! !!_____________________________________________________! ! Committee Co-Chairperson!! !!_____________________________________________________! Committee Co-Chairperson!!! ! ! ! University of California, Riverside!! ! !Acknowledgements ! ! Thank you, coffee and online banking and MacBook Air.! Thank you, professors, for cracking me open and putting me back together again: Elizabeth Crane, Jill Alexander Essbaum, Mary Otis, Emily Rapp, Rob Roberge, Deanne Stillman, David L. Ulin, and Mary Yukari Waters. ! Thank you, Spotify and meditation, sushi and friendship, Rancho Las Palmas and hot running water, Agam Patel and UCR, rejection and grief and that really great tea I always steal at the breakfast buffet. ! Thank you, Joshua Mohr and Paul Tremblay and Mark Haskell Smith and all the other writers who have been exactly where I am and are willing to help. ! And thank you, Tod Goldberg, for never being satisfied with what I write. !Dedication! ! ! For Misty. Because I promised my first book would be for you. ! For my hygges. Because your friendship inspires me and motivates me. ! For Jason. Because every day you give me the world.! For Everest. Because. !Table of Contents! ! ! !You are braver than you think !! ! ! ! ! ! 5! !When you feel defeated, stop to catch your breath !! ! ! 26! !Push yourself until you can’t turn back !! ! ! ! ! 40! !You’re not lost. -

Federal Republic Ofnigeria

wee . - “te. -“ fee= - . oa wes ™ LO we Same ¢, . rs 3* ae nN RB ArmA Baevaee fo iven COTE,avansreses Pre a Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette No.55 ° 7 oe Lagos- 21st September, 1989 Vol. 76 CONTENTS Page Movementsof Officers - - oe -« 878-903 Ministry of Defence—Nigerian Army—Dismissal, Voluntary Retirements, Discipline, Resignation, , Conversion, Award of Medals and Promotions . -- 90417 . ‘Trade Dispute Between the National Union of Road ‘TransportWorkers and Lagos State Transport Corporation 2 ee - “ -. 917 Trade Dispute Between the National Union of Hotels and Personal Services Workers and Unical Hotel, Calabar . -. .. as +. 917-18 Notice of Registration of Alteration of Trade Union Rules under Section 27 and 49 of the Trade ‘Union Act 1973 .. + 918 Loss of Custom Document . a - 919 AirTransport Licensing Regulations 1965 .s . os oe 919 Registration of Insurance Company o oe oe 919 Exemption and Extension of Exemption from the Provisions of Part "%?of the Companies Decree, 1968 underPowers Conferred bythe Companies (Special Provisions) Decree No. 19 of 1973 ++ 920-22 878 OFFICIAL GAZETTE No. 55, Vol. 76 Government Notice No. 502 ; NEW ASTOINTMENTS AND: OTHER STAFF CHANGES ‘The following are notified for general information — NEW APPOINTMENTS . Department Name Appointment Date of Appointment Cabinet Office .. .. Idoghor, Miss M. ..| Clerical Officer 10-4-89 , Olajide, O «|: Motor Driver 6-6-78 © Popoola, F. Motor Driver _ 18-8-88 Civil ServiceCommission Adejumo,O, ..|, Assistant Craftsman we. 6-3-83 Ezeh, A. N. .4> Typist, Grade II .»: 21-12-79. Jjeh, F. -| Motor Driver - 17-3-80° John, O. -| Motor Driver =... 18-5-81 Oguno, Miss Cc, N. -

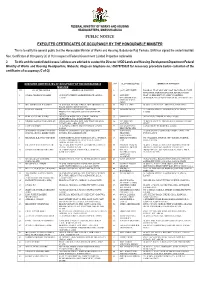

Executed Certificates of Occupancy by the Honourable Minister

FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WORKS AND HOUSING HEADQUARTERS, MABUSHI-ABUJA PUBLIC NOTICE EXECUTED CERTIFICATES OF OCCUPANCY BY THE HONOURABLE MINISTER This is to notify the general public that the Honourable Minister of Works and Housing, Babatunde Raji Fashola, SAN has signed the underlisted 960 Nos. Certificates of Occupancy (C of O) in respect of Federal Government Landed Properties nationwide. 2. To this end the underlisted lessees / allotees are advised to contact the Director / HOD Lands and Housing Development Department Federal Ministry of Works and Housing Headquarters, Mabushi, Abuja on telephone no.: 08078755620 for necessary procedure before collection of the certificates of occupancy (C of O). EXECUTED CERTIFICATES OF OCCUPANCY BY THE HONOURABLE S/N ALLOTTEE/LESSEE ADDRESS OF PROPERTY MINISTER S/N ALLOTTEE/LESSEE ADDRESS OF PROPERTY 31. (SGT) OTU IBETE ROAD 13, FLAT 2B, LOW COST HOUSING ESTATE, RUMUEME, PORT HARCOURT, RIVERS STATE 1 OPARA CHARLES NNAMDI 18 BONNY STREET, MARINEE BEACH, APAPA, 32. ANIYEYE FLAT 18, FED. DEPT OF AGRIC QUARTERS, LAGOS OVUOMOMEVBIE RUMMODUMAYA PORT HARCOURT, RIVERS STATE CHRISTY TAIYE (MRS) 2 MR. ADEBAYO S. FALODUN ALONG OGUNNAIKI STREET, OFF ADIGBOLUJA 33. ARO A.A. (MR.) BLOCK 55, PLOT 1302, ABESAN, LAGOS STATE ROAD, OJODU, OGUND STATE. 3 HUMAIRI AHMED HOUSE NO. 6, UYO STREET, GWARINPA 34. AHMADU MUSA 15, SAPARA STREET, MARINE BEACH, APAPA, PROTOTYPE HOUSING SCHEME GWARINPA, LAGOS ABUJA 4 FEMI AJAYI (MR. & MRS) NO 48, KOLA ORETUGA STREET, MEIRAN 35. UMAR ALI A. 9B BATHURST ROAD, APAPA, LAGOS ALIMOSHO L.G.A., LAGOS STATE 5 NWOGU EARNEST NWAOBILOR HOUSE 64B, ROAD 8, FED. LOW COST HOUSING 36. -

Ape Rescue Chronicle

The Springfield Country Hotel, Leisure Club & Spa is set within six acres of beautiful landscaped gardens at the foot of the Purbeck Hills. Charity No. 1126939 superior and executive rooms, are all you would expect from a country house hotel, some with balconies and views of our beautifully landscaped gardens. A PE R ESCUE C HRONICLE Situated in one of the most beautiful parts of the country, just We also boast a Leisure Club with a Issue: 66 SPRING 2017 a few minutes’ drive from Lulworth well-equipped gym, heated indoor Cove, Monkey World, Corfe Castle, swimming pool, sauna, steam Swanage Steam Railway and the room, large spa bath, snooker beaches of Swanage and Studland, room, 2 squash courts, outdoor we are just a short drive from the tennis courts and an outdoor Jurassic Coast which has been swimming pool, heated during the awarded World Heritage status. summer months. At the Springfield we have combined So whether your stay is purely for the atmosphere of a country house pleasure, or you are attending an with all the facilities of a modern international conference or local hotel. The comfort of all 65 meeting you can be sure of a true bedrooms, with a choice of standard, Dorset welcome. www.thespringfield.co.uk EXCLUSIVE OFFERS! Monkey World Adoptive Parents receive a free night when booking one or more nights – including Full English Breakfast, Leisure Club & Free WIFI! Guests who are not Adoptive Parents receive free tickets to Monkey World when staying one or more nights! See www.thespringfield.co.uk/monkey-world-offers for details. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Newsletter Igbo Studies Association

NEWSLETTER IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 ISSN: 2375-9720 COVER PHOTO CREDIT INCHSERVICES.COM PAGE 1 VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 EDITORIAL WELCOME TO THE FIRST EDITION OF ISA NEWS! November 2014 Dear Members, I am delighted to introduce the first edition of ISA Newsletter! I hope your semester is going well. I wish you the best for the rest of the academic year! I hope that you will enjoy this maiden issue of ISA Newsletter, which aims to keep you abreast of important issue and events concerning the association as well as our members. The current issue includes interesting articles, research reports and other activities by our Chima J Korieh, PhD members. The success of the newsletter will depend on your contributions in the forms of President, Igbo Studies Association short articles and commentaries. We will also appreciate your comments and suggestions for future issues. The ISA executive is proud to announce that a committee has been set up to work out the modalities for the establishment of an ISA book prize/award. Dr Raphael Njoku is leading the committee and we expect that the initiative will be approved at the next annual general meeting. The 13th Annual Meeting of the ISA taking place at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is only six months away and preparations are ongoing to ensure that we have an exciting meet! We can’t wait to see you all in Milwaukee in April. This is an opportunity to submit an abstract and to participate in next year’s conference. ISA is as strong as its membership, so please remember to renew your membership and to register for the conference, if you have not already done so! Finally, we would like to congratulate the newest members of the ISA Executive who were elected at the last annual general meeting in Chicago. -

The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: a Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3

THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND U.S. General Services Administration VOL. 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: Burial African York New History and of the Archaeology Biology, Skeletal The THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Volumes of A Synthesis Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc Research, Statistical by Prepared . The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. ISBN: 0-88258-258-5 9 780882 582580 HOWARD UNIVERSITY HUABG-V4-Synthesis-0510.indd 1 5/27/10 11:17 AM THE NEW YORK AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York Volume 4 The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology, and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 Prepared by Statistical Research, Inc. HOWARD UNIVERSITY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. 2009 Published in association with the United States General Services Administration The content of this report is derived primarily from Volumes 1, 2, and 3 of the series, The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York. Application has been filed for Library of Congress registration. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. General Services Administration or Howard University. Published by Howard University Press 2225 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite 720 Washington, D.C. -

Return: the Counter-Diasporic Migration of German-Born Turks to Turkey

MIM Research Seminar 8: 11 April 2013 ‘Euro-Turks’ return: the counter-diasporic migration of German-born Turks to Turkey Russell King* and Nilay Kılınçᶧ * Willy Brandt Guest Professor of Migration Studies, Malmö University 2012-13 ᶧ Intern at MIM, Malmö University, and MA student in European Studies, Lund University Outline of Seminar • Turkish migration to Europe and Germany, and the ‘Euro-Turk’ phenomenon • Theoretical and contextual background: the second generation, counter-diaspora, transnationalism, and return migration • Three main research questions: pre-return, return, and post-return • Research methods and sites: Istanbul and Black Sea coast, 35 participant interviews • Findings: growing up ‘Turkish’ in Germany • Findings: five narratives of return • Findings: post-return experiences, achievements, and disappointments • Conclusion 1 Introducing Turkish migration to Europe • Turkey is the largest single source country for immigration into Europe, mainly to Germany, but also substantial numbers in the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as the UK, France, Austria, Sweden, Denmark and elsewhere • Turkish migration to Germany is the third largest in the world (after Mexico US and Bangladesh India). Estimated ‘stock’ of 2.7 million Turks in Germany, where they are the largest group • Turkish migration to Germany was classic labour migration, managed by bilateral recruitment agreements 1961-64. Following Robin Cohen’s (1997) typology of diasporas, it is a labour diaspora • Labour migration Turkey Germany heavily concentrated in years 1961-73, but with a qualitative change within those years: initially from urban areas of Turkey, people with above-average education and skills; later, lower-educated unskilled workers from rural Turkey 2 Guestworkers, Settlers, ‘Euro-Turks’ • Turks in Germany are classic case of ‘guests who stayed for good’ as the Gastarbeiter soon became (semi-)permanent settled community. -

Through September 1991 10/30/91

THROUGH SEPTEMBER 1991 PAGE 10/30/91 COMMITTEE INDEX FOR GCC DESCRIPTION REY # 105 -91GNa Authorized Meetings 1991 91-0000123 105 -91GNb Authorized Meetings 1992 91-0000127 117-91G Historic Stand for Temperance Principles - -Statement 91-0000106 140-91G Invitation to Overseas Div Presidents - -Sp Meeting & Premeetings 91-0000105 141-91G Employee Remuneration and Allowance Review Com - -1991 Sp Meeting 91-0000105 143-91G Annual Global Baptism Day 91-0000130 144 -91GN Authorized Meetings - -Locations 91-0000131 145 -91GN Use of Economy Hotels and Motels 91-0000131 149-91G Funding for Graduate Educ at GC Insts in NAD - Task Force Appt 91-0000131 149-91G Graduate Programs at GC Educational Institutions - -Task Force Appt 91-0000131 150-91G World Children's Ministries Advisory/Convention 91-0000109 151-91G International Year of the Family 1994 91-0000109 154-91G Availability of Sabbath School Quarterlies 91-0000112 155-91G Stewardship Reaffirmation Statement 91-0000112 156-91G Financial Report to Church Membership 91-0000113 157-91G Certification of Stewardship Ministry Directors 91-0000114 158-91G International Workshop on Youth Evangelism 1992 91-0000111 159-91G Year of Youth Evangelism 1993 91-0000109 161-91G Interdivision Youth Congresses 91-0000141 161-91G World Youth Congresses 91-0000141 163-91G World Commission on Youth - Appointment 91-0000116 166-91G Board of Regents Appointments 91-0000107 169 -91GN ASI Status 91-0000107 171-91G Annual Council 1991 - -Division Reports 91-0000108 174 -91GN NAD Tithe Percentages Adjustment - -Operating -

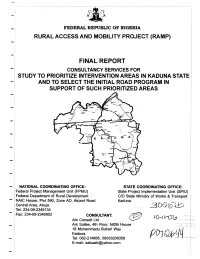

Final Report

-, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA RURAL ACCESS AND MOBILITY PROJECT (RAMP) FINAL REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR STUDY TO PRIORITIZE INTERVENTION AREAS IN KADUNA STATE - 1AND TO SELECT THE INITIAL ROAD PROGRAM IN SUPPORT OF SUCH PRIORITIZED AREAS STATE COORDINATING OFFICE: - NATIONAL COORDINATING OFFICE: Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) 'Federal Department of Rural Development C/O State Ministry of Works & Transport Kaduna. - NAIC House, Plot 590, Zone AO, Airport Road Central Area, Abuja. 3O Q5 L Tel: 234-09-2349134 Fax: 234-09-2340802 CONSULTANT:. -~L Ark Consult Ltd Ark Suites, 4th Floor, NIDB House 18 Muhammadu Buhari Way Kaduna.p +Q q Tel: 062-2 14868, 08033206358 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction 1 Scope and Procedures of the Study 1 Deliverables of the Study 1 Methodology 2 Outcome of the Study 2 Conclusion 5 CHAPTER 1: PREAMBLE 1.0 Introduction 6 1.1 About Ark Consult 6 1.2 The Rural Access and Mobility Project (RAMP) 7 1.3 Terms of Reference 10 1.3.1 Scope of Consultancy Services 10 1.3.2 Criteria for Prioritization of Intervention Areas 13 1.4 About the Report 13 CHAPTER 2: KADUNA STATE 2.0 Brief About Kaduna State 15 2.1 The Kaduna State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy 34 (KADSEEDS) 2.1.1 Roads Development 35 2.1.2 Rural and Community Development 36 2.1.3 Administrative Structure for Roads Development & Maintenance 36 CHAPTER 3: IDENTIFICATION & PRIORITIZATION OF INTERVENTION AREAS 3.0 Introduction 40 3.1 Approach to Studies 40