Olympic Fantasy Camp Fit Or Fat – with Chutzpah and a Few Bucks, You Too Can (Almost) Be an Olympian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers Game Dame

This Day In Sports 1973 — UCLA, led by Bill Walton, sets an NCAA record for consecutive victories with its 61st win, an 82-63 victory over Notre Numbers Game Dame. UCLA breaks the record of 60 set by San Francisco in 1956. C4 Antelope Valley Press, Sunday, January 27, 2019 FIGURE skating | U.S. CHAMPIONSHIPS Morning rush Cain, LeDuc win U.S. Valley Press news services from Breeders’ Cup Classic champion Accel- American snaps Germany’s 24-race erate for an emphatic victory in the final Rose settles for 3-shot lead at Torrey bobsled winning streak race before retirement for both horses. ST. MORITZ, Switzerland — Elana title, Chen in first Pines City of Light and Accelerate were neck- SAN DIEGO — Justin Rose had three Meyers Taylor of the United States won a and-neck on the lead as the 12-horse field Associated Press straight national title. big mistakes and still kept a three-shot lead World Cup women’s bobsled race Saturday, turned for home on a rainsoaked track and Ashley Cain and Tim- Saturday with a 3-under 69 at the Farmers ending Germany’s 24-race winning streak DETROIT — Nathan under a very dark, stormy sky. But Accel- Chen took the lead at othy LeDuc won the pairs Insurance Open. in World Cup and Olympic bobsled races Rose had six birdies and an eagle on an- erate didn’t fire, and City of Light under dating back to last season. the U.S. Figure Skating competition, and Madison jockey Javier Castellano simply took off. Championships with a other pristine day along the Pacific, and he Hubbell and Zach Dono- Schmidhofer wins super-G race, dazzling short program stretched his lead to six shots at one point Venezuela defends role as series Saturday and is in great hue won their second along the back nine of the South course. -

Olympic Winter Games Brain Teaser I

OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES BRAIN TEASER I Jason, Jennifer, Will, Marianne, Eddie, Graciela, and Yasmin are part of the United States Olympic team. They are each from a different state. (Hawaii, Alaska, Oregon, New Hampshire, Texas, New Mexico, and Utah) and they are also each competing in a different event (freestyle skiing, speedskating, figure skating, snowboarding, curling, skeleton, and ice hockey). Figure out the state each person is from and the event in which he or she is competing. The person competing in the snowboarding event is from New The person competing in the freestyle skiing event is from the England. This is his second time at the Games. Southwest. This is her third time at the Games. The person competing in the figure skating event is from the Yasmin and Graciela have never been to Utah before. Southwest. This is her second time at the Games. The person from Texas is not competing in the skeleton event. The person from Texas and her friend invited the person from Alaska to dinner. The person from Alaska thought it was a great Graciela and Eddie are not from New Mexico. idea, and she gladly accepted. Eddie has never been to Texas. Yasmin had lunch with someone she met. The person she met is competing in the figure skating event. Marianne did not compete in the curling or figure skating events. The person competing in the skeleton event is from a Rocky Mountain state. This is her third time at the Games. The person from New Mexico is not competing in the skeleton event. -

Mountain Bike Trail Development Concept Plan

Mountain Bike Trail Development Concept Plan Prepared by Rocky Trail Destination A division of Rocky Trail Entertainment Pty Ltd. ABN: 50 129 217 670 Address: 20 Kensington Place Mardi NSW 2259 Contact: [email protected] Ph 0403 090 952 In consultation with For: Lithgow City Council 2 Page Table of Contents 1 Project Brief ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Project Management ....................................................................................................................... 7 About Rocky Trail Destination .......................................................................................................... 7 Who we are ......................................................................................................................................... 7 What we do .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Key personnel and assets ................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Project consultant .......................................................................................................................... 11 Project milestones 2020 .................................................................................................................. 11 2 Lithgow as a Mountain Bike Destination ........................................................................................... -

International Bobsleigh Rules 2015

International Bobsleigh Rules 2015 2015_International Rules_BOBSLEIGH Release Date: June 2015 1 of 75 Table of Contents 1. IBSF COMPETITIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Olympic Winter Games .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Senior Olympic Winter Games ........................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1.2 Youth Olympic Winter Games ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Championships ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1 Senior World Championships ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.2 Junior World Championships .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.3 Continental Championships ............................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Official IBSF Competitions .................................................................................................................................... -

Aspen Snowmass Aspen

SNOWMASS THE CIRQUE • • • • • • • • 12,510 FT • • • • • • • • • • TRAIL INFORMATION • • 3,813 M • • • • • • • • HIKING • • • • HIGH ALPINE• • • • • • • • • • • • BIG BURN 11,852 FT • • ELK CAMP GONDOLA & CHAIRLIFT RIDES CIRQUE • • & BIKING • • • • 3,612 M • • 11,835 FT • • • • • • • Ride the Elk Camp Gondola to mid-mountain reaching nearly 10,000 feet • 3,607 M • SNOWMASS • • • • • • • and then continue up the Elk Camp Chairlift to the 11,325-foot summit! • • • • • • • • • • • • • Mountain bikers get fired up for more than 50 miles of trails ranging from • • • • • • • • gentle roads to the challenging downhill terrain of Valhalla. More thrills can • • HIGH ALPINE • • • • • ELK CAMP • • • be found with a climbing wall, Eurobungy and two disc golf courses. Make • VAPOR TRAIL • • • • • • • 11,325 FT • • • • • • • • • • • • • sure you stop by Elk Camp restaurant, offering great meal options in a • SAM’S• KNOB • • 3,452 M • • SUMMIT TRAIL BIG BURN • • • • SHEER BLISS SHEER • ADVENTURE AWAITS IN 10,620 FT• • cafeteria-style setting with a full bar. • • • • 3,237 M • • • SUMMER • June 23 - September 4, 2017 2018 • DAILY: • • • • • • • • • • • • • September 9-10, 16-17, 23-24, September 30 - October 1 • • WEEKENDS: Lost Forest is a new mountain adventure experience that didn’t forget • • MAROON BELLS SNOWMASS • • • SIERRA CLUB LOOP • • ELK CAMP CHAIRLIFT • • WILDERNESS AREA • • ELK CAMP GONDOLA HOURS: 10 am - 4 pm (last ride down at 4:15 pm) the mountain. Tucked in among the trees and rocks will be an alpine • • • • SAM’S KNOB • • • • • • • coaster and zip lines, new downhill mountain biking trails, ropes • 10 am - 3 pm (last ride down at 3:15 pm) • ELK CAMP ELK CAMP CHAIRLIFT HOURS: • • • • MEADOWS LOOP • • • challenges and climbing walls. -

X Games LEVELED BOOK • W a Reading A–Z Level W Leveled Book Word Count: 1,370

X Games LEVELED BOOK • W A Reading A–Z Level W Leveled Book Word Count: 1,370 Connections Writing What about X Games makes it extreme? Write a paragraph explaining your ideas. Social Studies Choose an extreme sports athlete highlighted in the book. Research the player, including his or her extreme sports career and major accomplishments. Then, write a short biography of his or her life. X Games Written by Sean McCollum Visit www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. www.readinga-z.com Words to Know athletes passionate competition promote consumers propel controversial ramp extreme sports scoffed obstacles stunts Cover: Nicole Hause, an American skateboarder, practices at X Games Minneapolis in 2017. Page 1: Kelly Sildaru of Estonia competes in a skiing event at X Games Oslo in 2016. Page 3: American skateboarder Dashawn Jordan practices at X Games Minneapoliis in 2017. Credits: Front cover, back cover: © David Berding/Icon Sportswire/AP Images; title page, page 9: Action Plus Sports Images/Alamy Stock Photo; pages 3, 11 (top right): © Aaron Lavinsky/ TNS/Newscom; page 4: © Tony Donaldson/ICON SMI/Newscom; page 6 (top left): © Jamie Squire/Getty Images Sport/Getty Images; page 6 (bottom left): © Eric Risberg/AP Images; page 6 (right): © Action Plus/Icon SMI 532/Action Plus/Icon SMI/Newscom; page 7: © Chris Polk/AP Images; page 8 (top left, top right): © Adam Pretty/Getty Images Sport/ Getty Images; page 8 (bottom): © Kyle Meyr/Red Bill Content Pool/AP Images; page 10: X Games Westend61 GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo; page 11 (top -

The Long-Term Athlete Development Plan for Snowboarding in Canada “It Takes 10 Years of Extensive Practice to Excel in Anything.” Introduction H

The Long-Term Athlete Development Plan for in Canada Table of Contents Foreword ......................................................................................... 2 Introduction ...................................................................................... 3 Where are we now? .......................................................................... 4 Where would we like to be? .............................................................. 5 How are we going to get there? ........................................................ 5 STEP 1: The 11 key factors influencing LTAD ................................. 6 STEP 2: The 8 stage Athlete Development Model ............................ 6 STEP 3: Putting it all in operation .................................................... 7 The 11 key factors influencing LTAD 1. The Ten-Year Rule .................................................................. 8 2. The FUNdamentals ................................................................. 9 3. Early and late specialization ...................................................10 4. Developmental Age ...............................................................11 5. Windows of opportunity ........................................................12 6. Physical, technical, tactical and psychological development ....................................................13 7. Periodization .........................................................................14 8. Calendar planning for competition .........................................15 -

SKATEBOARDING DOWNHILL and STREET LUGE REGULATION Updated on 14 Feb 2019

WORLD SKATEBOARDING COMMISSION SKATEBOARDING DOWNHILL & STREET LUGE REGULATION 1 INDEX INDEX ............................................................................................................................2 1 COMPETITORS .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Obligations and Code of Conduct ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Liability Waiver ................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.3 Riding Ability ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Pregnant Women .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.5 Pre-Race Technical Inspection of Equipment ................................................................................. 7 1.6 Junior Category ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.6.1 Juniors Competing in Open Categories .......................................................................................... 7 1.7 Masters Category ............................................................................................................................................. -

And Curlers, Too

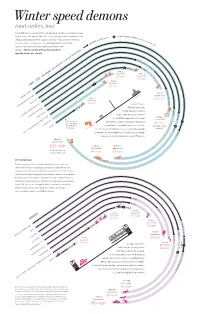

Winter speed demons (and curlers, too) A downhill skier vs. a bobsled? A comically dressed curler vs. a brawny hockey player? Sure, each sport is dierent — some more graceful, others more death SOCHI AVERAGE ic) SPEE ital D (ev D ( ents defying, and all performed in varying conditions — but all share something PEE thr S oug GE h W A ed in common: the need for speed. e Washington Post analyzed the ER ne V sd A ay speeds of all major disciplines represented in the Sochi ) Olympics. is is how far and how fast an athlete typically travels per second: S now bo ar d c ro ss , 35 31 37 m mph m p ph h 37 feet per second 54 feet TOP SPEED: TOTAL DISTANCE TRAVELED PER SECOND 25 mph per second 37 mph 29 feet Cr. country per second MEN 20 mph S k 15-16mph i j u 73 feet m p i per second n g Capitol , DOWNHILL SKIER 16 feet 50 mph 5 per second 0 m p SKELETON 11 mph Johan Clarey, a h FOUR-MAN BOBSLED/LUGE French alpine skier, 6.5 mph h hit 101 mph while compet- p m 7 ing in a 2013 World Cup downhill 5 h p SKI JUMPER/SNOWBOARDFREESTYLE CROSSSKI CROSS 88 feet m SPEED SKATER event. At that speed, he could rocket 8 per second 5 Once released, from the U.S. Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial the curling stone 60 mph averages about — a distance of about two miles — in 1 minute FIGURE SKATER Ski jumper’s speed CURLER 3 to 4 mph. -

Bulletin 3 Partners

World Masters Championships 21–24 January 2016 www.ski-orienteering.de Bulletin 3 Partners Organizers Bulletin 3 Ski Orienteering World Masters Championships 2016 Dear ski orienteers around the world, on behalf of all members of the organizing committee we welcome you to the Ski Orienteering World Cup 2015–2016 and the World Masters Orienteering Championships Ski in the Ore Mountains in Germany. In the Ore Mountains winter sports has a long tradition. For 100 years, competitions in cross-country skiing, ski jumping and luge races will organized. 1. Organizers 2. Event controllers 3. Competition office 4. Programme 5. Venue 6. Classes and entry regulations 7. Embargoed areas 8. Summary of Entries 9. Maps and scales 10. Terrain type and opportunities for training 11. Description of competition area and weather conditions 12. Electronic punching system 13. Waxing facilities 14. Transport and parking 15. Complaints 16. Registration for WMSOC and entry fees 17. Registration for open races and entry fees 18. Payment 19. Accommodation types and fees 20. Visas 21. Media service 22. How to get to Oberwiesenthal and Klingenthal 23. Culture excursion 2 Bulletin 3 Ski Orienteering World Masters Championships 2016 1. Organizers Organizer Deutsche Ski-Orientierungslauf Gemeinschaft 2016 e.V. Host International Orienteering Federation, Deutscher Turner-Bund e.V. Event director Bernd Kohlschmidt, Diethard Kundisch Competition secretary Christine Kohlschmidt Course Planner Harald Männel, Renate Tröße Address Diethard Kundisch, Altlaubegast 10, 01297 Dresden, Germany E-mail address [email protected] Web site http://ski-orienteering.de/ 2. Event controllers IOF Event Advisor Milan Venhoda (CZE) National Controller Wolfgang Pötsch (AUT) 3. -

Race Analyses Among Winter Olympic Sliding Sports: a Cross-Sectional Study of the 2018/2019 World Cups and World Championships

Original Article Race analyses among Winter Olympic sliding sports: A cross-sectional study of the 2018/2019 World Cups and World Championships MARKUS WILLIAMS 1 Department of Sports Performance, United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee, Lake Placid, United States of America ABSTRACT Studies about the three Olympic sliding sports are sparse, little is known other than factors related to start performance. Therefore, this study aimed to add to the current literature by analysing the race characteristics of the nine different events. A non-experimental retrospective method was applied to analyse all races of the 2018/2019 season. A total of 3371 race trials sampled across the sports of bobsleigh (n = 1105), luge (n = 1401) and skeleton (n = 865). Split rankings were correlated to finish rankings using Pearson product-moment correlation to analyse the relationship of sectional rankings and race outcome throughout the race. The results exhibited sequentially increasing correlation coefficients in all events. Yet, there were distinctive characteristics differentiating the sports. Bobsleigh illustrated correlations coefficients that at a minimum were very large (r ≥ .71) among all split rankings. Luge and skeleton depicted lower correlations for split 1 (r = .30 – .68) and thereafter substantially increasing as the race progressed. Thus, sliding performance can potentially have a greater impact in luge and skeleton than in bobsleigh. The differentiating race characteristics show the need for different training methods. Keywords: Olympic sports; Bobsleigh; Luge; Skeleton; Performance analysis. Cite this article as: Williams, M. (2021). Race analyses among Winter Olympic sliding sports: A cross-sectional study of the 2018/2019 World Cups and World Championships. -

Canadian Sport Institute & BC Bobsleigh & Skeleton Association

Canadian Sport Institute & BC Bobsleigh & Skeleton Association (BCBSA) Athlete and Coach Nomination Criteria Criteria Approved September 6, 2016: CSI Pacific Representative Signature BCBSA Representative Signature CANADIAN SPORT INSTITUTE / PACIFICSPORT / BCBSA ATHLETE AND COACH NOMINATION PURPOSE The Canadian Sport Institute, through a partnership with the Province of BC and ViaSport, the network of PacificSport Centres, and BCBSA collaborates to deliver programs and services to place BC Athletes1 on National Teams, and ensure athletes and coaches have every advantage to win medals for Canada. The partners work jointly to encourage sport excellence and increase podium performances in communities throughout British Columbia. Canadian Sport Institute / PacificSport athlete and coach support for the Canadian Development and Provincial Development nomination focuses on athletes and teams 5-12 years from the Podium, identified by the sport specific Podium Pathway (see Figure 1 below) and Gold Medal Profile. These athletes and teams represent both the next generation (5-8 years from Podium) and future generations (9-12 years from Podium) of Olympic and Paralympic (or World Championship) medalists. Support may be focussed more toward the future generation (9-12 years from Podium) for some targeted Paralympic sports depending on the quality of the next generation (5-8 years from Podium) of athletes and teams. Figure 1 PSO/NSO/CSI/PacSport Supported 1 In general a BC athlete is defined as an athlete born, developed, and/or trained/centralized (for a minimum of three months) in British Columbia. DETAILS Through the above partnership, and with the above purpose in mind, BCBSA may nominate athletes and their coaches who meet specific criteria for Canadian Sport Institute / PacificSport athlete or coach registration.