Senate Task Force on Public Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Report of the Massachusetts Autonomous Vehicles Working Group

REPORT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES WORKING GROUP DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION PURPOSES ONLY – ACTIVE POLICY DEVELOPMENT v4.0 Submitted Pursuant to Executive Order 572 September 12, 2018 DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION PURPOSES ONLY – ACTIVE POLICY DEVELOPMENT Table of Contents 1 Autonomous Vehicles Working Group Members ................................................................. 3 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4 3 Connected and Autonomous Vehicles – Technology Overview ...................................... 7 3.1 C/AV Industry in Massachusetts .......................................................................................................... 11 4 Governance ..................................................................................................................................... 14 5 Policy Considerations ................................................................................................................. 18 5.1 Establishing a C/AV Committee ........................................................................................................... 20 5.2 Engaging First Responders and Law Enforcement ...................................................................... 22 5.3 Moving From Executive Order to Regulation ................................................................................. 23 5.4 Establishing Legislation ......................................................................................................................... -

Nicholas Saggese Bruce Tarr

Awards Banquet ~ October 27th, 2018 Nicholas Saggese Detective (Ret.) Boston Police Department 2018 Recipient Saint Michael e Archangel Award Bruce Tarr State Senator (First Essex and Middlesex District) 2018 Recipient Saint Michael e Archangel Award 194 South Main Street, Middleton, MA 01949 978-777-2196 Proud Supporter of Masschusetts Association of Italian American Police Officers Massachusetts Association of Italian American Police Officers, Inc. SINCE 1968 Association President’s Message Welcome to the 50th Annual Awards Banquet of the National /Massachusetts Italian American Police Officer’s Association Dear Friends, Since 1968 the National Association of Italian American Police Officers has been promoting the role of law enforcement in our communities and honoring our Italian Heritage. This is the 50th year as an Association and we continue to provide recognition of the courageous actions of members of law enforcement in their efforts to preserve the peace and maintain order. The Association was started by a group of Boston Police Department Officers that sought to organize for upward mobility in the department and in celebration of their Italian Heritage. Over the years the organization has expanded throughout Massachusetts and around the country. We have members in Florida, California, Texas, and Illinois to name a few. Law enforcement careers are one of the few where each day you do not know what violent or potentially life threatening event you may be confronted with. So far in 2018, 110 officers have been killed in the line of duty. Despite some highly publicized incidents of rouge officers dishonoring the badge the vast majority of officers work hard every day to protect the public and control crime. -

Justice Reinvestment in Massachusetts Overview

Justice Reinvestment in Massachusetts Overview JANUARY 2016 Background uring the summer of 2015, Massachusetts state leaders STEERING COMMITTEE Drequested support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Charlie Baker, Governor, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and The Pew Charitable Robert DeLeo, House Speaker, Massachusetts House of Representatives Trusts (Pew) to use a “justice reinvestment” approach to develop Ralph Gants, Chief Justice, Supreme Judicial Court Karyn Polito, Lieutenant Governor, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts a data-driven policy framework to reduce corrections spending Stan Rosenberg, Senate President, Massachusetts Senate and reinvest savings in strategies that can reduce recidivism and improve public safety. As public-private partners in the Justice WORKING GROUP Reinvestment Initiative (JRI), BJA and Pew approved the state’s Co-Chairs request and asked The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice William Brownsberger, State Senator, Second Suffolk and Center to provide intensive technical assistance to help collect and Middlesex District Paula Carey, Chief Justice, Massachusetts Trial Court analyze data and develop appropriate policy options for the state. John Fernandes, State Representative, Tenth Worcester District Lon Povich, Chief Legal Counsel, Office of the Governor State leaders established the CSG Justice Center-Massachusetts Criminal Justice Review, a project led by a bipartisan, interbranch Members James G. Hicks, Chief, Natick Police steering committee and working group to support the justice Anthony Benedetti, Chief Counsel, Committee for Public reinvestment approach. The five-member steering committee is Counsel Services composed of Governor Charlie Baker, Lieutenant Governor Karyn Daniel Bennett, Secretary, Executive Office of Public Safety and Polito, Chief Justice Ralph Gants, Senate President Stan Rosenberg, Security (EOPSS) and House Speaker Robert DeLeo. -

Cwa News-Fall 2016

2 Communications Workers of America / fall 2016 Hardworking Americans Deserve LABOR DAY: the Truth about Donald Trump CWA t may be hard ers on Trump’s Doral Miami project in Florida who There’s no question that Donald Trump would be to believe that weren’t paid; dishwashers at a Trump resort in Palm a disaster as president. I Labor Day Beach, Fla. who were denied time-and-a half for marks the tradi- overtime hours; and wait staff, bartenders, and oth- If we: tional beginning of er hourly workers at Trump properties in California Want American employers to treat the “real” election and New York who didn’t receive tips customers u their employees well, we shouldn’t season, given how earmarked for them or were refused break time. vote for someone who stiffs workers. long we’ve already been talking about His record on working people’s right to have a union Want American wages to go up, By CWA President Chris Shelton u the presidential and bargain a fair contract is just as bad. Trump says we shouldn’t vote for someone who campaign. But there couldn’t be a higher-stakes he “100%” supports right-to-work, which weakens repeatedly violates minimum wage election for American workers than this year’s workers’ right to bargain a contract. Workers at his laws and says U.S. wages are too presidential election between Hillary Clinton and hotel in Vegas have been fired, threatened, and high. Donald Trump. have seen their benefits slashed. He tells voters he opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a very bad Want jobs to stay in this country, u On Labor Day, a day that honors working people trade deal for working people – but still manufac- we shouldn’t vote for someone who and kicks off the final election sprint to November, tures his clothing and product lines in Bangladesh, manufactures products overseas. -

Legislative Profiles Spring 2019 |

Legislative Profiles Spring 2019 | Announcement Inside This Issue This portfolio contains the profiles of all legislators that belong to PG. 2: Forward key committees within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. PG. 4: House Bill – H.2366 Each key committee will play a role in the review and approval of the retirement bills that have been filed. PG. 8: Senate Bill – SD.1962 PG. 11: Joint Committee on Public Service – Profiles PG. 29: House Ways & Means – Profiles This portfolio is for the members of MCSA to use to determine PG. 63: House Committee on Third Reading – Profiles which members reside within their regions so contact can be made with each legislator for support of both retirement bills. PG. 67: Senate Ways & Means – Profiles PG. 86: Senate Committee on Third Reading – Profiles PG. 92: Talking Point Tips PG. 93: Legislative Members by MCSA Regions FORWARD Many of us do not have experience with advocating for legislation or meeting with our legislative representatives. This booklet was created with each you in mind to assist in determining which members reside within your region or represent your town and city. We request you contact your respective legislators for support of both retirement bills. If you are familiar with the legislative process and your representatives this may seem rudimentary. The Massachusetts Legislature is comprised of 200 members elected by the people of the Commonwealth. The Senate is comprised of 40 members, with each representing a district of approximately 159,000 people. The House of Representatives is comprised of 160 members, with each legislator representing districts consisting of approximately 40,000 people. -

2020 Annual Report

Essex County Sheriff's Department 2020 Annual Report SHERIFF KEVIN F. COPPINGER Table ooff Contents Sheriff’s Message i Executive Team Photos 1 Department Policy, Mission Statement & Correctional Officer’s Core Values 2 Sheriff Kevin F. Coppinger 3 By the Numbers 4 Department Overview 5 Department’s Three Correctional Facilities 7 Middleton Facility 7 Classification _ 9 Programs & Treatment 12 Chaplaincy 15 Specialized Re-Entry Services 16 Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) 16 Clean and Sober Existence (CASE) 19 Correctional Alternatives for Re-Entry (CARE) 22 Essex Medication Assisted Treatment Program (EMAT) 22 Essex County Mental Health Diversion Program 23 Correctional Opportunity for Personal Enrichment (COPE) 24 Essex County Pre-Release and Re-Entry Center 25 Programs & Treatment 26 Career Training 28 Education 29 The Farm 30 Profiles in Perseverance 31 Women In Transition Facility 32 Community Service & Work Release 34 Offices of Community Corrections 36 One-Year Recidivism Rates 40 Daily Workings of ECSD 41 Middleton Intake 41 Criminal Records 41 Transportation 42 Inmate Property 43 Video Conferencing 43 Central Control 45 Outer Perimeter Security 46 Female Holding Area 47 Visits 47 Tool Control 47 Key Control 48 Inmate Mail 48 DNA Collection 48 Armory 49 Incident Command Structure 50 Housing Units, Inspections, & Audits 51 Environmental Health & Safety/Fire Safety 51 Housing Units 52 Audits 54 Office of Professional Standards____________ 56 Centralized Scheduling 58 Human Resources 59 Training & Staff Development 67 Internal -

MA CCAN 2020 Program FINAL

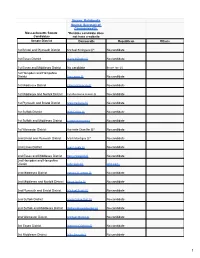

Source: Ballotpedia Source: Secretary of Commonwealth Massachusetts Senate *Denotes candidate does Candidates not have a website Senate District Democratic Republican Others 1st Bristol and Plymouth District Michael Rodrigues (i)* No candidate 1st Essex District Diana DiZoglio (i) No candidate 1st Essex and Middlesex District No candidate Bruce Tarr (i) 1st Hampden and Hampshire District Eric Lesser (i) No candidate 1st Middlesex District Edward Kennedy (i) No candidate 1st Middlesex and Norfolk District Cynthia Stone Creem (i) No candidate 1st Plymouth and Bristol District Marc Pacheco (i) No candidate 1st Suffolk District Nick Collins (i) No candidate 1st Suffolk and Middlesex District Joseph Boncore (i) No candidate 1st Worcester District Harriette Chandler (i)* No candidate 2nd Bristol and Plymouth District Mark Montigny (i)* No candidate 2nd Essex District Joan Lovely (i) No candidate 2nd Essex and Middlesex District Barry Finegold (i) No candidate 2nd Hampden and Hampshire District John Velis (i) John Cain 2nd Middlesex District Patricia D. Jehlen (i) No candidate 2nd Middlesex and Norfolk District Karen Spilka (i) No candidate 2nd Plymouth and Bristol District Michael Brady (i) No candidate 2nd Suffolk District Sonia Chang-Diaz (i) No candidate 2nd Suffolk and Middlesex District William Brownsberger (i) No candidate 2nd Worcester District Michael Moore (i) No candidate 3rd Essex District Brendan Crighton (i) No candidate 3rd Middlesex District Mike Barrett (i) No candidate 1 Source: Ballotpedia Source: Secretary of Commonwealth -

Shadow Transit Agency: When These by MICHAEL JONAS Three Transportation Policy Wonks Speak, the MBTA Listens

DEMOCRACY ISN’T WORKING IN MASSACHUSETTS GANGS/ELECTIONS/UTILITIES/NURSES/TRANSITMATTERS POLITICS, IDEAS & CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS Shadow transit agency commonwealthmagazine.org FALLSUMMER 2017 2017 $5.00$5.00 When these three wonks speak, FALL 2017 FALL the MBTA listens Leaders in both the public and private sectors rely on The MassINC Polling Group for accurate, unbiased results. You can too. Opinion Polling Market Research Strategic Consulting Communications Strategies DATA-DRIVEN INSIGHT MassINCPolling.com @MassINCPolling (617) 224-1628 [email protected] T:7.5” Our people have always been the ones behind the HERE’S TO continued success of Partners HealthCare. And for the past 24 years, it’s been the people—68,000 strong—who have helped our hospitals rank on the prestigious U.S. News & THE PEOPLE World Report “Best Hospitals Honor Roll.” WHO POWER This year, in addition to our nationally ranked founding hospitals, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, we congratulate McLean T:10.5” PARTNERS Hospital and the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, which were recognized nationally for their specialties. We HEALTHCARE also extend our congratulations to our neighbors at Beth Israel Deaconess, Tufts Medical Center, and Children’s Hospital for their national recognition. And as we do every year, we wish to thank our employees for helping lead the way with their achievements. For us, this recognition is always about more than a ranking. It’s about providing the highest quality care, innovating for the future, and ensuring our community continues to thrive. This is Partners HealthCare. A legacy of knowing what counts in high quality health care. -

Massachusetts Senate

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS MASSACHUSETTS SENATE Monday, January 22, 2018 For Immediate Release Contact: Pat Johnson (Sen. Cyr’s office): 508-241-6200 (cell) Kelsey Brennan (Sen. Rodrigues’ office) 774-766-7562 (cell) State Senate Task Force Holds Events on Cape & Islands Retail Economy Senators Cyr Hosts Colleagues to Learn about the Region’s Business Climate (Hyannis, MA): The Massachusetts State Senate Task Force on Strengthening Local Retail visited Cape Cod today to meet with small businesses and the general public to hear about the regional retail economy and learn what steps the Senate could take to strengthen local retail business on Cape Cod, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. The Task Force held a hearing in Hyannis at Alberto’s Ristorante, located on Main Street that was hosted by Senator Cyr (D-Truro). The task force also met for lunch with local business owners at Land Ho! Harwich Port. And task force members visited local businesses in Harwich Port with leaders from the Harwich Chamber of Commerce. “Small retailers are the center of our towns and regional economy,” said Senator Cyr. “Local retail shop owners are struggling to maintain a decent share of the market, while competing with the pervasiveness of online shopping. Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket experience the added difficulty of navigating seasonal fluctuations. I am grateful to be a member of this task force to give a voice to our communities.” Last September former Senate President Stanley Rosenberg (D-Amherst) and Minority Leader Bruce Tarr (R-Gloucester) appointed the task force members, which included bipartisan representation from the state Senate and business leaders from the private sector. -

Annual Town Report

Annual Town Report Town of Ipswich 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 4 Roster of Town Officials and Committees Annual Town Meeting 13 Special Town Meetings 33 General Government Board of Selectmen 56 Finance Committee 57 Town Manager 57 Department of Public Safety Police Department 59 Public Safety Communications 62 Emergency Management 63 Animal Control 64 Harbors 65 Shellfish 67 Fire 69 Department of Public Works Public Works Divisions 70 Facilities Department 73 Cemeteries/Parks Department 75 Building Department 76 Department of Public Health 77 Department of Planning and Development Planning Board 83 Conservation Commission 84 Historical Commission 86 Housing Partnership 87 Open Space Committee 88 Agricultural Commission 89 Department of Human Services Recreation Department 92 Council on Aging 93 Veterans’ Services 94 1 Department of Utilities Electric Department 95 Water Division 96 Wastewater Treatment 97 Finance Directorate Accounting Office 98 Purchasing and Management Services 99 MIS Department 99 Treasurer/Collector 100 Assessors’ Office 101 Town Clerk 102 Elections and Registrations 103 Ipswich Public Library 106 School Department 108 Shade Tree Beautification 116 Trust Fund Commission 117 Financial Statements 2016 118 2 TOWN OF IPSWICH FACTS AT A GLANCE Government Incorporated in 1633 Open Town Meeting, Five member Board of Selectmen and a Town Manager Annual Town Second Tuesday in May each Year. Meeting Town Census 13,256 Population 2015 Registered Voters 10,069 2015 Square Miles of Area 42.5 Total Area Town Hall Address Ipswich Town Hall 25 Green Street Ipswich MA. 01938 978-356-6600 United States Elizabeth Warren, Edward Markey Senators 317 Hart Office Building 255 Dirksen Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, D.C. -

January 27, 2021

January 27, 2021 His Excellency Governor Charlie Baker Massachusetts State House 24 Beacon Street Office of the Governor, Room 280 Boston, MA 02133 Delivered Electronically and via Certified Mail Dear Governor Baker, We, the Merrimack Valley Superintendents Association, write to you as a unified group of 22 school superintendents joined in this effort by all 22 of the union presidents in our respective districts, to respectfully request that you reclassify educators and make them eligible to receive COVID-19 vaccinations during Phase 1 of the vaccination process. We cite the guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in urging you to prioritize the health and well-being of our educators so that Massachusetts school districts can operate at the fullest possible strength as our nation begins to emerge from this global pandemic. In making our request, we cite the following: 1. Your office and the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) have drawn from the guidance and wisdom of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which strongly advocates for students to return to, at a minimum, an in-person hybrid learning model. AAP further advocates that students should fully return to the classrooms where and when possible. 2. We, as educators and leaders, recognize and agree that the best place for learning for our children is in the classroom. 3. We have a profound responsibility to support the educational, emotional, physical, and mental well-being of the children across the Commonwealth. 4. First responders, healthcare workers, and educators share a commonality in their work in that they must come into contact with dozens or hundreds of people daily and often cannot be completely socially distant from those they serve. -

Cloudfront.Net

Would vote against abortion Would vote against Districts Candidates on-demand. Doctor-Prescribed Suicide Berkshire, Hampshire, Franklin, and Hampden Adam G. Hinds (D) Bristol and Norfolk Paul Feeney (D) X X 1st Bristol and Plymouth Michael Rodrigues (D) Mixed 2nd Bristol and Plymouth Mark Montigny (D) X Cape and Islands Julian Cyr (D) X 1st Essex Diana DiZoglio (D) Mixed 2nd Essex Joan Lovely (D) X X 3rd Essex Brendan Crighton (D) X 1st Essex and Middlesex Bruce Tarr (R ) Mixed 2nd Essex and Middlesex Barry Finegold (D) X Hampden James T. Welch (D) X 1st Hampden and Hampshire Eric Lesser (D) X 2nd Hampden and Hampshire Donald Humason, Jr. (R) ü ü Hampshire, Franklin and Worcester Chelsea Kline (D) X 1st Middlesex Ed Kennedy (D) X 2nd Middlesex Patricia D. Jehlen (D) X X 3rd Middlesex Michael J. Barrett (D) X X 4th Middlesex Cindy Friedman (D) X 5th Middlesex Jason Lewis (D) X 1st Middlesex and Norfolk Cynthia Stone Creem (D) X X 2nd Middlesex and Norfolk Karen Spilka (D) X Middlesex and Suffolk Sal DiDomenico (D) X Middlesex and Worcester James B. Eldridge (D) X X Norfolk, Bristol, and Middlesex Rebecca (Becca) Rausch (D) X Norfolk, Bristol, and Plymouth Walter Timilty (D) ü ü Norfolk and Plymouth John Keenan (D) X ü Norfolk and Suffolk Michael F. Rush (D) ü ü Plymouth and Barnstable Vinny deMacedo (R) ü ü 1st Plymouth and Bristol Marc Pacheco (D) Mixed ü 2nd Plymouth and Bristol Michael Brady (D) Plymouth and Norfolk Patrick O'Connor (R) Mixed ü 1st Suffolk Nick Collins (D) ü ü 2nd Suffolk Sonia Chang-DiaZ (D) X 1st Suffolk and Middlesex Joseph A.