Download Redacted Final Form Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PMA MS First Fill Form

For the following states please utilize the below group To the Injured Worker: number: AL, AR, AZ, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MS, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, VT, WI On your first visit, please give this this notice to any pharmacy listed on the back side to speed processing your approved workers’ compensation prescriptions (based on the guidelines established by your employer). Questions or need assistance locating a participating retail network pharmacy? Call the Express Scripts Patient Care Contact Center at 800.945.5951. KVQA Atencion Trabajador Lesionado: Este formulario de identificación para servicios temporales de prescripción de recetas por For all other States, please utilize the below Group number: compensación del trabajador DEBERÁ SER PRESENTADO a su farmacéutico al surtir su(s) receta(s) inicial(es). Si tiene cualquier duda o necesita localizar una farmacia participante, por favor contacte al área de Atención a Clientes de Express Scripts, en el teléfono 800.945.5951. L7EA To the Pharmacist: Express Scripts administers this workers’ compensation To the Supervisor: Please fill in the prescription program. Please follow the steps below to submit a claim. Standard claim limitations include information requested for the injured worker. quantity exceeding 150 pills or a day supply exceeding 14 days. This form is valid for up to 30 days from DOI. Employee Information Limitations may vary. For assistance, call Express ________________ ______ _________________________ First M Last Scripts -

Board of Directors Election

09/30/2003 Page 159 Board of Directors Election Excerpts from Texas Property Tax Code Section 6.03 Board of Directors (e) The chief appraiser shall calculate the number of votes to which each taxing unit other than a conservation and reclamation district is entitled and shall deliver written notice to each of those units of its voting entitlement before October 1 of each odd-numbered year. The chief appraiser shall deliver the notice: (1) to the county jUdge and each commissioner of the county served by the appraisal district; (2) to the presiding officer of the governing body of each city or town participating in the appraisal district, to the city manager of each city or town having a city manager, and to the city secretary or clerk, if there is one, of each city or town that does not have a city manager; and (3) to the presiding officer of the governing body of each school district participating in the district and to the superintendent of those school districts. (g) Each taxing unit other than a conservation and reclamation district that is entitled to vote may nominate by resolution adopted by its governing body one candidate for each position to be filled on the board of directors. The presiding officer of the governing body of the unit shall submit the names of the unit's nominees to the chief appraiser before October 15. m Before October 30,. the chief appraiser shall prepare a ballot, listing the candidates whose names were timely submitted under Subsection (g), alphabetically according to the first letter in each candidate's surname, and shall deliver a copy of the ballot to the presiding officer of the governing body of each taxing unit that is entitled to vote. -

First Fill Temporary Pharmacy Card Making It Easy to Get Your Workers’ Compensation Prescriptions Filled

First Fill Temporary Pharmacy Card Making it easy to get your workers’ compensation prescriptions filled. Employer: Print this page immediately upon receiving notice of injury, fill in the information below and give it to your employee. Injured Employee: 1. If you need a prescription filled for a work-related injury or illness, go to a Tmesys network pharmacy. 2. Give this page to the pharmacist. 3. The pharmacist will fill your prescription at no cost. Attention Pharmacists: Call 800.964.2531 to establish First Fill benefit eligibility and obtain the ID# for online adjudication Prescription Card of approved benefits for the injured worker. CARRIER/TPA EMPLOYER/OTHER ENTITY Tmesys is the designated PBM for this patient. Sedgwick CLIC INJURED WORKER NAME Tmesys Pharmacy SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBER DATE OF INJURY Help Desk 800.964.2531 Please provide directly to Pharmacist Notice to Cardholder: This card should be presented to your pharmacy to receive NDC Envoy medication for your work-related injury. It is only valid within 30 days of your date of injury. RxBin 004261 or 002538 For information regarding the program or to find nearby pharmacies call 866.599.5426. RxPCN CAL or Envoy Acct. # (To create a card for your wallet, cut along outer line and fold in half.) Pharmacist: 1. Call the Tmesys Pharmacy Help Desk at 800.964.2531. 2. Provide the information listed above. 3. The Help Desk will provide an ID number for adjudication. Finding a Network Pharmacy Use one of these easy methods to find a network pharmacy: ■ Visit one of the following pharmacy chains: Walgreens Walmart Duane Reade Publix Rite Aid CVS Kroger Safeway ■ Use our pharmacy locator online: www.pmsionline.com/pharmacy-center. -

Grocer's Week in Michigan

The Magazine for the Michigan Food Market FEBRUARY, 1975 February 16 thru 221“GROCER’S WEEK IN MICHIGAN” 59th Anniversary Issue Nothing downbeat here... no blue notes. That’s because Pepsi Cola delivers the happiest, rousingest taste in cola. Get the one with a lot to give. Pass out the grins with Pepsi... the happiest taste in cola. Join The Pepsi People ...Feelin’ Free The Food Dealer • February, 1975 Page 3 OFFICERS - 1975 LOUIS VESCIO, President Vescio Super Markets PHIL LAURI, Chairman Lauri Bros. Super Market PHIL SAVERINO, Vice-President Phil’s Quality Market THE FOOD DEALER EDWARD ACHO, Vice-President Official publication of THE ASSOCIATED FOOD DEALERS J-A Super Markets 434 West 8 Mile Road, Detroit, Ml 48220 • Phone: 542-9550 JERRY YONO, Vice-President Bond Market VOLUME 49 - No. 1 • COPYRIGHT 1975 WILLIAM WELCH, Treasurer Hollywood Super Markets EDWARD DEEB EDWARD DEEB, Editor Executive Director JUDITH MacNICOL, Office Secretary GEORGE N. BASHARA, SR. RENE’ SANDERSON, Insurance Secretary Legal Advisor DIRECTORS TERMS EXPIRING DEC. 31, 1975 STAN ALBUS President’s M essage........................................... ... Page 6 Stan’s Super Markets GEORGE BYRD Byrd House of Meats Off the Deeb E n d ..................................................................8 ROBERT COVERSON Mardi-Gra Food Center PAUL FELICE Guest Editorial by Peter Stroh.................................. ... 10 Felice’s Quality Market DON HARRINGTON Meat-N-Place Around the Town ........................................................... 12 GENE MATTI Town Square Market RAY SHOULDERS Brokers Hear Predictions...............................................22 Shoulders Markets LEONARD TAGLIAVIA Dan-Dee- Super Markets AFD Officers, D ire c to rs...............................................20 FRED WEBER Short Stop Stores Merchandising N o te s .....................................................38 GARY WING Fisher’s Markets TERMS EXPIRING DEC. -

Massachusetts Avenue Project

Food For Growth A Community Food System Plan for Buffalo’s West Side MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE PROJECT IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING FALL 2003 Food REPORT AUTHORS Tangerine Almeida Mark Bostaph For Mikaela Engert Samuel Gold Growth Jeanne Leccese A Community Food System Plan for Buffalo’s West Side Jordana Maisel Anjali Malhotra Joanna Rogalski Advisors Dr. Samina Raja, University at Buffalo Tatiana Vejar Department of Urban and Regional Planning Keigo Yokoyama Ms. Diane Picard, Massachusetts Avenue Project Lesley Zlatev Report layout and design Jeanne Leccese WE WOULD LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE FOLLOWING INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANIZATIONS FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS DURING THE PLANNING PROCESS. Jerrod Blair Corinne Giannini Oswaldo Mestre, Jr. Paula A. Rosner Nick Bonifacio David Haight Melanie Nowicki Tamar Rothaus Sister Susan Bowles The Hubers Jim Pavel Kate Sheldon Jodi Bryon LaDonna Knigge Diane Picard Michelle Stieglitz Clem Eckert Jill Lemke Steve Porter Ron Thaler Kathryn Foster Beverly McClean The Ritchies Joann Tomasulo All the drawings in the report were created by third graders in the public schools on the West Side. The two pieces of artwork on the cover were created by Wesley Beasley and Arta Krasniai. Both were awarded top honors in the Food for Growth Art Contest. The printing of this report was made possible by the generous support of Buffalo’s Weed and Seed Program FOOD FOR GROWTH: A COMMUNITY FOOD SYSTEM PLAN FOR BUFFALO ’S WEST SIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgment 3. Strengthening the Community Food System on the West Side of Buffalo 29 Executive Summary 3.1. -

A Tract Level Analysis of the Food Landscape in Syracuse, New York

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Honors Theses 5-2013 Identifying Communities of Concern: A Tract Level Analysis of the Food Landscape in Syracuse, New York Michelle Meyer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors Part of the Nutrition Commons, and the Social Welfare Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Michelle, "Identifying Communities of Concern: A Tract Level Analysis of the Food Landscape in Syracuse, New York" (2013). Honors Theses. 9. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Identifying Communities of Concern: A Tract Level Analysis of the Food Landscape in Syracuse, New York by Michelle Meyer Candidate for Bachelor of Science Department of Environmental Studies With Honors May 2013 APPROVED Thesis Project Advisor: ______________________________ Myrna H. Hall Second Reader: ______________________________ Dr. Lee Herrington Honors Director: ______________________________ William M. Shields, Ph.D. Date: ______________________________ Abstract Food security is defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as access by all members of the household to enough food to live an active, healthy life at all times [1]. Food security has also been identified as an important public health concern, subsequently amplifying interest in identifying communities with limited accessibility to quality food retailers. The primary focus of this analysis was to identify communities of heightened food security concern in Syracuse, NY based on three measures of physical accessibility: proximity to the nearest grocer, diversity of grocers within 1km, and variety of grocers based on the average distance to the three nearest grocers; and social deprivation. -

Merck-Medco Lifewise Select National Network Participating

Merck-Medco LifeWise Select National Network Participating Chains* A Giant Quality Markets Giant Eagle Markets A & P Giant Pharmacy R Acme Good Neighbor PlusCare Allscripts Healthcare Solutions Pharmacies Raleys Arbor H Ralphs Arrow Randalls Aurora Pharmacy Haggen Food & Pharmacy Rite Aid Hannaford Food & Drug Riverside Pharmacy B Happy Harry's Discount Drug Rosauers Supermarkets Harris Teeter Pharmacy S Bartell Drug Company Hart Drug Store Basha’s HEB Pharmacy Safeway Bel Air Hi-School Pharmacy Sav-A-Center Bi-Lo Pharmacy Homeland Pharmacy Save Mart Supermarkets Bi-Mart Corporation Horizon Pharmacies Schnuck Markets Big B Hy-Vee Pharmacies Seaway Foodtown Big Bear Shaw's Brooks Pharmacy K Shop n Save Food & Drug Brooks-Maxi Drug Shop-Rite Brookshire Kmart ShopKo Stores Brookshire Brothers Kerr Drug Smiths Food & Drug King Sooper Snyder C Kinney Drugs Star Pharmacy Kroger Stop & Shop Pharmacy Carrs Super 1 City Market L Super D Cost Cutters Super Fresh Costco Pharmacies LaFeria Pharmacy Super G Pharmacy Cub Leader Drug Stores CVS Longs T D M Target Thrifty Jr. Dillon Major Value Pharmacy Network Thrifty White Drug Discount Drug Mart Marc's Tom Thumb Domincks Marsh Drugs TOP Food & Drug Drug Emporium Mays Drug Tops Markets Drug Fair Medic Drug Drug Warehouse Medicap Pharmacy U Drugs for Less Pharmacy Meijer Minyard Food Stores United Pharmacy E USA Drug N Eagle Food Centers V Eckerd Drug Stores NCS HealthCare EPIC Pharmacies Neighborcare Pharmacy VIX Pharmacy Vons F P W Fagen Pharmacy P & C Food Markets Family Fare Pamida Pharmacy Walgreen’s Familymeds Pharmacy Pathmark Pharmacy Wal*Mart Stores Farm Fresh Pharmacies Pavilions Waldbaums Farmer Jack Supermarket Pay Less Supermarkets Wegmans Food Markets Food Emporium Phar-Mor Weis Pharmacy Fred Meyer PharMerica White Drug Fred’s Price Chopper Pharmacy Winn-Dixie Frys Food & Drug ProCare Pharmacies Furrs Pharmacy Publix Super Markets G Q * with 25 or more stores September 5, 2001. -

Truman Says Aid Bill Step Toward Peace; Signs in Hotel Room

■ t ■ t * WEDNESDAY, MAY li, 194T PAOESCTTESIt iKaurljratfr €urnlttt}, Ifwali Aventfe Daily Circalation The Weather For tiM Mootb ot AprU, 1M1 PoroeMt of V. S. Weather Boreaa Jlfenilieih Of the Challoner Club! Light ihoaem ending thin eve Mancheater araitpe niembera The executive ommlttee of the W omena n u b will meet tomoe- will ny et at 7:4.1 tonight In front 9,298 ning, eleorlng nnd cooler toalght; are urged to attend the meeting of the W P Qiilah Kiinei-al Home, About Town . thla evening In the Maaonlc Tem i*,»w evi'iihvr with Ml-**. Il.'irley II. V (aiiiiit .Si/.p 22** X 3 6 “ Member of Ibo Audit Friday fair and aeoeonoMy wom --- - / DeWolfe ol 4<l Phelpa road. Th<> li. pay their leapecta to John F otcept for cooetol area. ple. aa a vote a-lll be taken to aec S.dlivan. whow .si.i, Joneph, i* a { Pui Your Home Jn Borauu of CItcttlaUoua The M ^ ’Stlon Ajrlny >'oiinf peo annual meeting la whediiled for whether or not the Grange will luemlwr of the elub. Niagara (llircknl ple will meet IdniRht at the cita purcfiaae the property, on Harl- Mondav evening at the South Manchester— A City of Village Charm T del with l* ^ erh e Qroeble in foW Road. The option on the new Methodiet chill eh. Piiiil Joiie.a of 23 Wellington idtarge. Thp profram will Include alte will expire before another PRICE POUR CENTS educatioi^ picturea and all mem- o ian g e meeting and the Z^mlng rood, uell-known |(m-b1 hiialness Shining Order -VOL. -

Quality Management

QUALITY MANAGEMENT Quality management Expanding the quality concept to satisfy consumer demand P.J. Batt Curtin University of Technology Perth AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Abstract Personal disposable income has a significant impact on the food consumers purchase, where they buy it and where they consume it. With increasing income there is a corresponding increase in the desire for more convenience, a greater variety of food and higher quality food. Quality can be conceptualized at five levels. At its most basic level, quality captures the consumers’ requirement for food that is nutritious, safe to eat and true to description. The intrinsic quality considers the physical attributes of the product. Extrinsic quality considers the value that the brand, the package, the place of purchase and the price add to the product. As attributes such as taste, texture and flavour can only be ascertained after purchase, such are described as the experiential quality attributes. The credence attributes are those that consider how the food was produced. With rising income, consumers want to know where the food was produced, what it contains and how it was produced. Concern for the environment, sustainable production and worker welfare and animal welfare are expected to become more influential in consumer decisions to purchase as they become more affluent. Introduction Personal disposable income has a significant impact on the food consumers purchase, where they buy it and where they consume it. With rising income comes a greater desire for more variety, more expensive and higher value foods in the diet (OECD−FAO, 2005). In general, as income increases, there is an increase in the consumption of meat, sugar, vegetable oils and dairy products and a parallel decrease in the consumption of roots and tubers, cereals and coarse grains. -

Chain List 2010

2010 PHARMACY CHAIN LIST A E K P S A&P Eaton Apothecary Katy Medical Center Pharmacy P & C Food Market & Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Accredo Health Group Econo Foods Pharmacy KD Pharmacy, Inc. Palaca Health Mart Pharmacy Strand Pharmacy Acme Pharmacy Etheckel Pharmacy Kearny Health Mart Pharmacy Pamida Pharmacy Stufflebeon Pharmacy AHS St. John Pharmacy F Kerr Drug Pantry Sun Mart Pharmacy Albertsons Pharmacy Fagen Pharmacy Kessel Pharmacy Pathmark Super 1 Pharmacy Albertsons Sav-on Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy King Kullen Pavilion Plaza Pharmacy, Inc. Super Fresh Allina Health System Family Fare King Soopers PayLess Drug Stores Super G Discount Drug Appalachian Regional Healthcare Inc Family Meds King's Pharmacy Pediatrics Pharmacy Super Rx Pharmacy Arbor Family Pharmacy Kinney Drugs Pelzel's Hometown Pharmacy Super-D Drug Store Arrow Prescription Center Farm Fresh Pharmacy Kiowa Hometown Pharmacy Pharmacy Center Sweetbay Supermarkets Aurora Pharmacy Farmacia Plaza Klein's Family Pharmacy Pharmerica T B Felpausch Pharmacy Klingensmith's Drug Store Pick N Save Target B&B Pharmacy Food 4 Less KLM Pharmacy, Inc. Piggly Wiggly Pharmacy Thrifty White Pharmacy Baker's Food City Pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy Powell Prescription Center Tiffany's Drug Baptist Pharmacy Food City United Drug Knight Drugs, Inc. Prairie Stone Pharmacy Times Pharmacy Bartell Drugs Food Lion Pharmacy Kroger Price Chopper Pharmacy Times Supermarket Bashas United Drug Food Pyramid L Price Cutter Pharmacy Tom Thumb Bel Air Pharmacy Food World Lewis Drug Price Wise Pharmacy Top Food & Drug Bi-Lo Foods Fred Meyer Lifechek Drug Professional Pharmacy Services Tower Pharmacy Bi-Lo, LLC Fred's Pharmacy Livingston Medical Pharmacy Publix Super Markets, Inc. -

The Clearscript Retail Pharmacy Network

The ClearScript Retail Pharmacy Network With more than 63,400 phamacies in the ClearScript Retail Pharmacy Network, you can have your prescription filled at most pharmacies. Major retail chains participating in the ClearScript Network are listed below. A AND H Pharmaceutical Family Thrift Services Familymeds A & P Pharmacies Farmacia Accredo Health Group Farm Fresh Acme Pharmacies Food City Pharmacies AHF Pharmacy Food 4 Less Albertsons Food Lion Pharmacies Allina Community FoodMax Pharmacy Pharmacies Food World Ameridrug Four Star Drug Apria Pharmacy Network Fred Meyer Pharmacies A-S Medications Fred’s Solutions LLC Fruth Pharmacy Bakers Pharmacies Fry’s Food & Drug Bartell Drugs Gemmel Pharmacy Group Bashas United Drugs Genoa Healthcare Best Drugs Gerbes Pharmacies Big A Drug Stores Giant Eagle Pharmacies Big Y Pharmacies Gristedes Pharmacy Biggs Pharmacy HEB Pharmacies Bi-Mart Pharmacies Happy Harry’s Discount BioScrip Pharmacies Drugs BK Pharmacies Harmons Pharmacy Brookshire Brothers Harps Pharmacy Marc’s Pharmacies Publix Pharmacy Synder Drug Stores Brookshire Pharmacy Harris Teeter Marsh Drugs QFC Pharmacy Southern Family Markets Bruno’s Food & Pharmacy Hartig Drug Company Martin’s Pharmacy QOL Meds Specialty Pharmacy Carle RX Express Harvest Foods Maxor Pharmacies Quality Markets St. John Pharmacies Carnival Pharmacies Harveys Supermarket Mays Drug Store Rainbow Pharmacies St. Joseph Mercy Pharmacy Carr’s Pharmacy Pharmacy Med-Equip Pharmacy Raley’s Standard Drug Company Chickasaw Nation Medical Health Insurance Plan of Med-Fast -

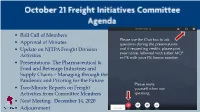

Roll Call of Members

• Roll Call of Members Please use the Chat box to ask • Approval of Minutes questions during the presentations • Update on NJTPA Freight Division and if requesting credits, please post your name, followed with either AICP Activities or PE with your PE license number • Presentations: The Pharmaceutical & Food and Beverage Industries and Supply Chains – Managing through the Pandemic and Pivoting for the Future Please mute • Two-Minute Reports on Freight yourself when not Activities from Committee Members speaking. • Next Meeting: December 14, 2020 • Adjournment • September 10 Truck Parking Workshop View and read the summary at: https://njtpa.org/Newsroom/NJTPA- News/NJPTA-Update- Blog/2020/September/Workshop-Calls-for- Expanding-Truck-Parking-Needed.aspx • Council on Port Performance • 2020 Port Economic Impact Report View and read the report at: https://njtpa.org/NJTPA/media/Documents/Planning/Regional- Programs/Freight/2020_NYSA_Economic_Impact.pdf • Third Quarter 2020 Industrial Real Estate Numbers – 851 million SF in NJTPA region, with 3 million in new starts • Pandemic Transportation and Supply Chain Implications • Freight Concept Development Program Learn more at www.njtpa.org/freight • The Pharmaceutical Please use the Chat box to ask Industry, Ronald T. questions during the presentations Piervincenzi, Ph.D., and if requesting credits, please post Chief Executive your name, followed with either AICP or PE with your PE license number Officer, United States Pharmacopeia • Food and Beverage Industry, Linda Doherty, President & Please