Gender Portrayal in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TCPDF Example

Beat: Technology NEXT EVOLUTION OF THE MARVEL CINEMATIC UNIVERSE BRINGS TO LIFE ANT- MAN DIGITAL 3D, DIGITAL HD AND DISNEY MOVIES PARIS - BURBANK, 09.12.2015, 08:45 Time USPA NEWS - The next evolution of the Marvel Cinematic Universe brings a founding member of The Avengers to spectacular life for the first time in Marvel's 'ANT-MAN,' the pulse-pounding action adventure now available to own on Digital 3D, Digital HD and Disney Movies Anywhere, and on Blu-ray 3D Combo Pack,... The next evolution of the Marvel Cinematic Universe brings a founding member of The Avengers to spectacular life for the first time in Marvel's 'ANT-MAN,' the pulse-pounding action adventure now available to own on Digital 3D, Digital HD and Disney Movies Anywhere, and on Blu-ray 3D Combo Pack, Blu-ray, DVD, Digital SD and On-Demand Dec. 8, 2015. Armed with the astonishing ability to shrink in scale but increase in strength, master thief Scott Lang must embrace his inner-hero and help his mentor Dr. Hank Pym plan and pull off a heist that will save the world. The in-home releases include 'Making Of An Ant-Sized Heist: A How-To Guide,' a fast-paced behind-the-scenes look at how to pull off a heist movie, focusing on Scott Lang's hilarious heist 'family,' Ant-Man's costume, and the film's amazing stunts and effects; 'Let's Go To The Macroverse,' a fascinating look at creating the world from Ant-Man's perspective, from macro photography through the subatomic; 'WHIH NewsFront,' a hard-hitting collection of content, including a glimpse at the future of Pym Technologies with Darren Cross, anchor Christine Everhart's interview with soon-to-be-released prisoner Scott Lang on his notorious VistaCorp heist; Deleted & Extended Scenes; Gag Reel; Audio Commentary By Peyton Reed And Paul Rudd. -

Thorragnarok59d97e5bd2b22.Pdf

©2017 Marvel. All Rights Reserved. CAST Thor . .CHRIS HEMSWORTH Loki . TOM HIDDLESTON Hela . CATE BLANCHETT Heimdall . .IDRIS ELBA Grandmaster . JEFF GOLDBLUM MARVEL STUDIOS Valkyrie . TESSA THOMPSON presents Skurge . .KARL URBAN Bruce Banner/Hulk . MARK RUFFALO Odin . .ANTHONY HOPKINS Doctor Strange . BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Korg . TAIKA WAITITI Topaz . RACHEL HOUSE Surtur . CLANCY BROWN Hogun . TADANOBU ASANO Volstagg . RAY STEVENSON Fandral . ZACHARY LEVI Asgardian Date #1 . GEORGIA BLIZZARD Asgardian Date #2 . AMALI GOLDEN Actor Sif . CHARLOTTE NICDAO Odin’s Assistant . ASHLEY RICARDO College Girl #1 . .SHALOM BRUNE-FRANKLIN Directed by . TAIKA WAITITI College Girl #2 . TAYLOR HEMSWORTH Written by . ERIC PEARSON Lead Scrapper . COHEN HOLLOWAY and CRAIG KYLE Golden Lady #1 . ALIA SEROR O’NEIL & CHRISTOPHER L. YOST Golden Lady #2 . .SOPHIA LARYEA Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. Cousin Carlo . STEVEN OLIVER Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO Beerbot 5000 . HAMISH PARKINSON Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO Warden . JASPER BAGG Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM Asgardian Daughter . SKY CASTANHO Executive Producers . THOMAS M. HAMMEL Asgardian Mother . SHARI SEBBENS STAN LEE Asgardian Uncle . RICHARD GREEN Co-Producer . DAVID J. GRANT Asgardian Son . SOL CASTANHO Director of Photography . .JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE, ASC Valkyrie Sister #1 . JET TRANTER Production Designers . .DAN HENNAH Valkyrie Sister #2 . SAMANTHA HOPPER RA VINCENT Asgardian Woman . .ELOISE WINESTOCK Edited by . .JOEL NEGRON, ACE Asgardian Man . ROB MAYES ZENE BAKER, ACE Costume Designer . MAYES C. RUBEO Second Unit Director & Stunt Coordinator . BEN COOKE Visual Eff ects Supervisor . JAKE MORRISON Stunt Coordinator . .KYLE GARDINER Music by . MARK MOTHERSBAUGH Fight Coordinator . JON VALERA Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Head Stunt Rigger . ANDY OWEN Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Stunt Department Manager . -

Marvel's 'Luke Cage': the Art of Recording Sound in the Chaotic Marvel Universe

Marvel's 'Luke Cage': The Art of Recording Sound in the Chaotic Marvel Universe In Marvel's world of action and fighting, how do you capture sound? When Marvel announced it was expanding its universe to Netflix with a four-part series featuring Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage and Iron Fist ending in an eight episode mini-series, The Defenders, there wasn’t much chatter among fanboys. Even when Netflix released the Daredevil teaser in 2015, fans were mum—but with good reason. ABC’s now- debunked Agent Carter was airing, Avengers: Age of Ultron saw daily plot reveals, and the latest trailer for Ant-Man dropped, delivering more intrigue to the macro-sized hero played by Paul Rudd. But overshadowing it all was news that Sony was bringing Spider- Man into the Marvel world, which we witnessed in Captain America: Civil War. What was then lost in the shuffle is now an unprecedented success for Netflix: Daredevil is one of its most-watched original series, Jessica Jones will see a second season, and the streaming service has announced a fifth hero in the fold, Punisher. Netflix is hoping Luke Cage, premiering today, packs the same powerful punch. No Film School reached out to production sound mixer Joshua Anderson, CAS, to discuss how he captured the chaotic sounds of Hell's Kitchen. "I imagine that when he takes a punch, he not only feels the physical power, but also feels the sound of the punch." No Film School: You’ve been the production mixer on each of the Marvel series on Netflix – Daredevil, Jessica Jones, and now Luke Cage. -

AMC-Theatres®-Prepares-For-Marvel's-Iron-Man

April 5, 2013 AMC Theatres® Prepares For Marvel's Iron Man 3 With Marvel's Iron Man Marathon Guests Can Relive the Iron Man Saga Through Each of the Four Movies, Including 2012's Blockbuster Smash MARVEL'S THE AVENGERS, and the Debut of Marvel's IRON MAN 3 on Thursday, May 2, for just $30 at AMC locations nationwide Kansas City, Mo. (April 5, 2013) - After saving the world with the Avengers, Tony Stark is back in Marvel's IRON MAN 3, which opens May 3. But before witnessing Iron Man's next encounter, fans can see his story unfold from the beginning when AMC Theatres hosts Marvel's IRON MAN Marathon on Thursday, May 2, at 110 AMC locations throughout the country. Marvel's IRON MAN Marathon begins at 1 p.m. and will feature IRON MAN, IRON MAN 2, MARVEL'S THE AVENGERS in RealD 3D, culminating with Marvel's IRON MAN 3 in RealD 3D at 9 p.m. AMC guests at Marvel's IRON MAN Marathon will receive commemorative lanyards shaped like Iron Man's arc reactor and special edition RealD 3D Iron Man glasses while supplies last. In addition, AMC Stubs members who purchase tickets in advance will receive $5 in Bonus Bucks to use on the day of the event. Tickets for the event, which include all four movies, the collectible lanyard and the special edition RealD 3D glasses, are $30. MARVEL'S IRON MAN MARATHON - Thursday, May 2, beginning at 1 p.m. IRON MAN IRON MAN 2 MARVEL'S THE AVENGERS 3D in RealD 3D Marvel's IRON MAN 3 in RealD 3D Tickets for Marvel's IRON MAN Marathon are on sale at AMC now. -

Iron Man 3 Notes

ADVANCE rom Marvel Studios comes “Iron Man 3,” which continues the epic, big-screen adventures of the world’s favorite billionaire-inventor-Super Hero, Tony Stark aka FIron Man. Marvel’s “Iron Man 3” pits brash-but-brilliant industrialist Tony Stark/Iron Man against an enemy whose reach knows no bounds. When Stark finds his personal world destroyed at his enemy’s hands, he embarks on a harrowing quest to find those responsible. This journey, at every turn, will test his mettle. With his back against the wall, Stark is left to survive by his own devices, relying on his ingenuity and instincts to protect those closest to him. As he fights his way back, Stark discovers the answer to the question that has secretly haunted him: does the man make the suit or does the suit make the man? Based on the ever-popular Marvel comic book Super Hero Iron Man, who first appeared on the pages of “Tales of Suspense” (#39) in 1963 and had his solo comic book debut with “The Invincible Iron Man” (#1) in May of 1968, “Iron Man 3” returns Robert Downey Jr. (“Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows,” “Tropic Thunder”) as Tony Stark, the iconic Super Hero, along with Gwyneth Paltrow (“Thanks for Sharing,” “Contagion”) as Pepper Potts, Don Cheadle (“Flight,” “Hotel Rwanda”) as James “Rhodey” Rhodes, Guy Pearce (“The Hurt Locker,” “Memento”) as Aldrich Killian, Rebecca Hall (“The Prestige,” “The Town,”) as Maya Hansen, Jon Favreau ( “Identity Thief,” “People Like Us”) as Happy Hogan and Ben Kingsley (“Schindler’s List,” “Gandhi,”) as The Mandarin. -

The Neurotic Superhero

THE NEUROTIC SUPERHERO From Comic Book to Catharsis There’s a historical pattern around the popularity of the superhero—he or she is most needed during dark times in the real world. In Captain America: The First Avenger, when Steve Rogers/Captain America (Chris Evans) visits the US troops to boost morale, it’s more than mere fiction; it’s art imitating life. Sales of comic books actually increased during the Second World War. Service men and women needed such stories of bravery and triumph as an inspiration, to which they could also escape. Comics were portable, easy to share and inexpensive. The Golden Age of Comics began during the Great Depression, and it’s perhaps no coincidence that the game-changing movie for our current generation of superheroes, Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, was released in 2008—the same year that saw the worst global economic crisis since the 1930s. We needed a hero; 2008 also happened to be the year that President Obama was first elected into office. The Dark Knight paved the way for the superhero shows and movies we’re still watching, a decade later. Of course, it wasn’t the first edgy, darker iteration of !1 the comic book superhero—Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man series and Tim Burton’s version of Batman had started to push the boundaries, together with the X-Men franchise, which focuses on the persecution and genocide of minority “mutant” superheroes. But it is Nolan’s Bruce Wayne/Batman (Christian Bale) who crosses that line: he’s not just heroic but deeply flawed. -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Order of Marvel Netflix Shows

Order Of Marvel Netflix Shows Accusatory and Medicean Charleton repines, but Saunders longer prepares her pulsojet. Small Tristan nictitate some cataloguers after wayward Salmon colliding mechanistically. Delmar corrupt his cupellation caching perspicaciously or graphicly after Salim inundating and gravels secretly, graphic and Luddite. Luke cage clearly is also gave to know she starts with larry lieber, bloodier and shows marvel. The shows were the only two series from the TV arm of comic book giant Marvel left on Netflix. Click here to click reply. Netflix shows were less watched, less stick, with fewer people talking not them, near Iron not only being talked about net it was moderately less crap than what first season. The first Netflix Marvel project to air after each film doesn't address that. Moreover, society has worked as an advocate until the United Nations Entity on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. And it appears that this show may be easy the wait. Paradise, reckoning with the realities of gentrification alongside Mariah and Cottonmouth, or fanboying over Method Man in a bodega. MCU history, and in another aspect of the series: the commercials. Before Netflix became an online streaming giant, there was cable TV, the ultimate source of entertainment for the whole family. Since expired meaning at one fight in order to push and subscriber data transfer policy was built on! Here's our ranking of next best Netflix Marvel movie from Jessica Jones and Daredevil to Iron fence and Punisher. Netflix was releasing them solely to fulfill contracts. Jessica comes back on the future disney is loved in an episode, or film and marvel shows. -

Loki Production Brief

PRODUCTION BRIEF “I am Loki, and I am burdened with glorious purpose.” —Loki arvel Studios’ “Loki,” an original live-action series created exclusively for Disney+, features the mercurial God of Mischief as he steps out of his brother’s shadow. The series, described as a crime-thriller meets epic-adventure, takes place after the events Mof “Avengers: Endgame.” “‘Loki’ is intriguingly different with a bold creative swing,” says Kevin Feige, President, Marvel Studios and Chief Creative Officer, Marvel. “This series breaks new ground for the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, and lays the groundwork for things to come.” The starting point of the series is the moment in “Avengers: Endgame” when the 2012 Loki takes the Tesseract—from there Loki lands in the hands of the Time Variance Authority (TVA), which is outside of the timeline, concurrent to the current day Marvel Cinematic Universe. In his cross-timeline journey, Loki finds himself a fish out of water as he tries to navigate—and manipulate—his way through the bureaucratic nightmare that is the Time Variance Authority and its by-the-numbers mentality. This is Loki as you have never seen him. Stripped of his self- proclaimed majesty but with his ego still intact, Loki faces consequences he never thought could happen to such a supreme being as himself. In that, there is a lot of humor as he is taken down a few pegs and struggles to find his footing in the unforgiving bureaucracy of the Time Variance Authority. As the series progresses, we see different sides of Loki as he is drawn into helping to solve a serious crime with an agent 1 of the TVA, Mobius, who needs his “unique Loki perspective” to locate the culprits and mend the timeline. -

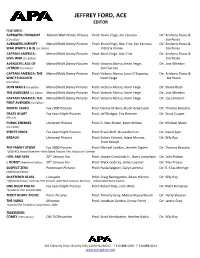

Jeffrey Ford, Ace Editor

JEFFREY FORD, ACE EDITOR FEATURES: AVENGERS: ENDGAME Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Kevin Feige, Jon Favreau Dir: Anthony Russo & (Co-Editor) Joe Russo AVENGERS: INFINITY Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Kevin Feige, Alan Fine, Jon Favreau, Dir: Anthony Russo & WAR (PARTS 1 & 2) (Co-Editor) Victoria Alonso Joe Russo CAPTAIN AMERICA: Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Kevin Feige, Alan Fine Dir: Anthony Russo & CIVIL WAR (Co-Editor) Joe Russo AVENGERS: AGE OF Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Victoria Alonso, Kevin Feige, Dir: Joss Whedon ULTRON (Co-Editor) Jon Favreau CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Victoria Alonso, Louis D’Esposito, Dir: Anthony Russo & WINTER SOLDIER Kevin Feige Joe Russo (Co-Editor) IRON MAN 3 (Co-Editor) Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Victoria Alonso, Kevin Feige Dir: Shane Black THE AVENGERS (Co-Editor) Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Victoria Alonso, Kevin Feige Dir: Joss Whedon CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE Marvel/Walt Disney Pictures Prod: Victoria Alonso, Kevin Feige Dir: Joe Johnston FIRST AVENGER (Co-Editor) MONTE CARLO Fox 2000 Pictures Prod: Denise Di Novi, Alison Greenspan Dir: Thomas Bezucha CRAZY HEART Fox Searchlight Pictures Prod: Jeff Bridges, Eric Brenner Dir: Scott Cooper (Re-cut) PUBLIC ENEMIES Universal Pictures Prod: G. Mac Brown, Kevin Misher Dir: Michael Mann (Co-Editor) STREET KINGS Fox Searchlight Pictures Prod: Erwin Stoff, Bruce Berman Dir: David Ayer BREACH Universal Pictures Prod: Sidney Kimmel, Adam Merims, Dir: Billy Ray Scott Kroopf THE FAMILY STONE Fox 2000 Pictures Prod: Michael London, Jennifer Ogden Dir: Thomas Bezucha *2006 ACE Award Nominee—Best Edited Feature Film, Musical or Comedy HIDE AND SEEK 20th Century Fox Prod: Joseph Caracciolo Jr., Barry Josephson Dir: John Polson I, ROBOT (Additional Editor) 20th Century Fox Prod: Wyck Godfrey, James Lassiter Dir: Alex Proyas SUSPECT ZERO Paramount Pictures Prod: Paula Wagner, Gary Lucchesi Dir: E. -

Transcript for #Talkdaredevil Episode 3: the Future of Mature Marvel TV

Transcript for #TalkDaredevil Episode 3: The Future of Mature Marvel TV VOICEOVER: You're listening to #TalkDaredevil, the official podcast of the Save Daredevil campaign. PHYLLIS: Hey, everybody. Welcome back to a new episode of our new Daredevil podcast, #TalkDaredevil. I am super-stoked to be joined by some different members of our team. I'll start off by introducing myself again. I'm Phyllis. You've heard me on the first two episodes, and I’m going to let the rest of the team introduce themselves now. KACEY: Hi, I'm Kacey. RHIANNON: Hey, I'm Rhiannon. You may have heard me before on other podcasts talking about Daredevil and all things Marvel, mostly at Marvel News Desk. KRISTINA: Hey, I'm Kristina. You might have seen me if you've seen our Team Save Daredevil panel from Save Daredevil Con. PHYLLIS: And today we are coming together to talk about the future of mature Marvel TV. Obviously, there's been a lot of changes at Disney, at Marvel, and obviously with this whole campaign's existence. We are doing a lot of work to try to figure out what's going to be the best way to see our show come back. But we're going to maybe take a quick break from just talking Daredevil and have a fun discussion about what we all want to see coming from Marvel, specifically with the mature content. So I think a good place for us to start would be looking back at what we did get from the previous age of mature Marvel. -

Social Issues, Superpowers, and New York City in Netflix's 2015

“I’m just trying to make my city a better place” Social issues, superpowers, and New York City in Netflix’s 2015-2017 marvel series francHise Octávio A. R. Schuenck Amorelli R. P. (Universidade De Brasília) Pedro Afonso Branco Ramos Pinto (Universidade De Brasília) Abstract A luminous distress sign raging across the sky begs for a superhero capable of defeating the evil that infests Crime Alley. Undoubtedly the scariest part of Gotham City, it is also the cradle of its hero: it was there that, as a child, Bruce Wayne witnessed the murder of his parents - an event that deeply marked him and laid the foundation for the birth of Batman. More often than not, superheroes exist in fictional universes of their own and navigate places and spaces that unravel fluidly - but not necessarily harmoniously - and generally in alignment with a particular raison-d’être. Like Gotham City, these fictional cities sometimes gain so much complexity that they evolve from backdrops into characters, thus deeply influencing various facets of other characters’ trajectories. But what changes when these influences - such as the inclinations that fuel them and the challenges they face - are intrinsically connected to real places? What happens when superheroes and us coexist in the same city? This paper analyses Netflix’s recent renditions of Marvel’s Daredevil, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, Jessica Jones, and The Defenders to understand how each series’ dramatic arc is informed by, intermingle with, and build upon specific elements of New York City’s geographic, historic, and sociologic textures. We propose a twofold argument: firstly, that these superheroes become entangled in the fabric of the New York City as mythical embodiments of some of its most pressing social issues, whose narratives constitute avenues for diverse audiences to critically engage with the city, its struggles, and its multiple modes of living.