Hagadda Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2015 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5775

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2015 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5775 Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons Featuring Divrei Torah from Rabbi Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Assaf Bednarsh Rabbi Josh Blass • Rabbi Reuven Brand Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman Rabbi Lawrence Hajioff • Rona Novick, PhD Rabbi Uri Orlian • Rabbi Ari Sytner Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner • Rabbi Ari Zahtz Insights on Yom Haatzmaut from Rabbi Naphtali Lavenda Rebbetzin Meira Davis Rabbi Kenny Schiowitz 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5775 We thank the following synagogues who have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Congregation Kehillat Shaarei United Orthodox Beth Shalom Yonah Menachem Synagogues Rochester, NY Modiin, Israel Houston, TX Congregation The Jewish Center Young Israel of Shaarei Tefillah New York, NY New Hyde Park Newton Centre, MA New Hyde Park, NY For nearly a decade, the Benajmin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go® series has provided communities throughout North America and Israel with the highest quality Torah articles on topics relevant to Jewish holidays throughout the year. We are pleased to present a dramatic change in both layout and content that will further widen the appeal of the publication. You will notice that we have moved to a more magazine-like format that is both easier to read and more graphically engaging. In addition, you will discover that the articles project a greater range in both scholarly and popular interest, providing the highest level of Torah content, with inspiration and eloquence. -

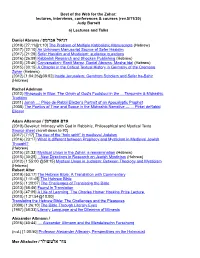

Best of the Web for the Zohar

Best of the Web for the Zohar: lectures, interviews, conferences & courses (rev.5/11/20) Judy Barrett a) Lectures and Talks דניאל אברמס / Daniel Abrams (2019) [27:11@1:10] The Problem of Multiple Kabbalistic Manuscripts (Hebrew) (2017) [22:10] An Unknown Manuscript Source of Sefer Hasidim (2017) [21:29] Sefer Hasidim and Mysticism: audience questions (2016) [26:09] Kabbalah Research and Shocken Publishing (Hebrew) (2015) [25:46] Conversation: Ronit Meroz, Daniel Abrams, Moshe Idel (Hebrew) (2015) [30:15] A Chapter in the Critical Textual History in Germany of the Cremona Zohar (Hebrew) (2012) [1:04:26@38:02] Inside Jerusalem: Gershom Scholem and Sefer ha-Bahir (Hebrew) Rachel Adelman (2012) Rhapsody in Blue: The Origin of God's Footstool in the ... Targumim & Midrashic Tradition (2011) Jonah ...: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer's Portrait of an Apocalyptic Prophet (2008) The Poetics of Time and Space in the Midrashic Narrative — ... Pirkei deRabbi Eliezer אדם אפטרמן / Adam Afterman (2019) Devekut: Intimacy with God in Rabbinic, Philosophical and Mystical Texts Source sheet (scroll down to #2) (2017) [7:17] The rise of the “holy spirit” in medieval Judaism (2016) [23:17] What is different between Prophecy and Mysticism in Medieval Jewish Thought? (Hebrew) (2015) [31:33] Mystical Union in the Zohar: a reexamination (Hebrew) (2015) [30:25] ...New Directions in Research on Jewish Mysticism (Hebrew) (2012) [1:55:00 @58:15] Mystical Union in Judaism: Between Theology and Mysticism (Hebrew) Robert Alter (2019) [53:17] The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (2018) [1:11:45] The Hebrew Bible (2015) [1:20:07] The Challenges of Translating the Bible (2013) [58:45] Found In Translation (2013) [47:09] A Life of Learning. -

Cutting-Edge Science Package Blossoms

קול “רמבם SUMMER 2015 dŠryz a`-fenz°oeiq KOL RAMBAM Cutting-Edge Science Package Blossoms Maimonides School is ready to launch an ence department coordinator Dr. ambitious seven-year enhanced instruc- Steven Stewart, following Mr. Mat- tional program of Middle and Upper School toon's assessment of all general science — defined as "a vision for our next- studies disciplines. He presented generation graduates." the details to Head of School Naty The multi-pronged approach will open with Katz and science faculty in Febru- expanded 90-minute weekly laboratory ses- ary, and they have been refining sions beginning with the 2015-16 academic the details since that time. year. Longer-range components include Mr. Mattoon defined the vision as upgrades in technology and physical infra- a blending of curricular and co- structure, selected elective opportunities, curricular lines into “a continuum and even online collaboration with stu- of knowledge, hands-on experi- dents and researchers at Technion in Haifa. ence, and application that goes Other goals are “fully-optimized” programs beyond our classroom walls.” in science, technology, engineering and This “robust blend of instructional mathematics (STEM); specialized electives efficacy in class with hands-on, for students in all the Middle and Upper experiential programs outside our School grades; internship programs in re- campus will build lasting scientific search labs for juniors and seniors; a visiting proficiency for 21st century Mai- instructor program “drawing on all sectors monides graduates,” Mr. Mattoon of scientific practice” in the region; and ad- said in his vision statement. ditional Advanced Placement options. Central to the proposal is a re- The proposal was designed by Scott Mat- vamped administrative structure toon, Middle and Upper School general that includes a science director. -

THE BENJAMIN and ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2016 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5776

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld April 2016 • Pesach-Yom Haatzmaut 5776 Dedicated in memory of Cantor Jerome L. Simons Featuring Divrei Torah from Rabbi Benjamin Blech • Rabbi Reuven Brand Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman • Rabbi Aaron Goldscheider Rabbi Yona Reiss • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner Ilana Turetsky, Ed.D • Rabbi Daniel Yolkut Insights on the Pesach Seder from the Rabbinic Alumni Committee of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Rabbi Binyamin Blau • Rabbi Eliezer Muskin • Rabbi Moshe Neiss Rabbi Shmuel Silber • Rabbi Eliezer Zwickler Insights on Yom Haatzmaut from Rabbi Nissim Abrin • Rabbi David Bigman • Mrs. Dina Blank Rabbi Jesse Horn • Rabbi Shaya Karlinsky • Rabbi Moshe Lichtman Rabbi Chaim Pollock • Rabbi Azriel Rosner • Rabbi Ari Shvat 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Pesach 5776 We thank the following synagogues who have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Congregation Ahavas Congregation Young Israel of Achim Shaarei Tefillah Century City Highland Park, NJ Newton Centre, MA Los Angeles, CA Congregation Ahavath The Jewish Center Young Israel of Torah New York, NY New Hyde Park Englewood, NJ New Hyde Park, NY Young Israel of Beth El in Congregation Beth Boro Park Young Israel of Shalom Brooklyn, NY West Hempstead Rochester, NY West Hempstead, NY Richard M. Joel, President -

Christian Friends of Israel

Fourth Quarter 2018 Jewish Year 5779 Christian Friends of Israel PO Box 1813 Jerusalem 9101701 ISRAEL Tel: 972-2-623-3778 Fax: 972-2-623-3913 [email protected] www.cfijerusalem.org For Zion’s Sake A Quarterly Publication / Printed in Israel EDITOR IN CHIEF MANAGING EDITOR / WRITER Stacey Howard Kevin Howard GRAPHIC DESIGNER COPY EDITOR The targeting of Jews worldwide Jennifer Paterniti Coral Mings should serve as a forewarning of WRITERS Marcia Brunson, Maggie Huang, Tiina Karkkainen, what we may expect in the future. Olga Kopilova, Jim McKenzie, and Patricia Cuervo Vera For Zion’s Sake is published by Christian Friends of Israel’s Jerusalem Office, free of charge to supporters. All articles may be quoted with proper attribution. Reproduction of any content of FZS magazine requires written permission. Direct inquiries to [email protected]. If you wish to help distribute CFI’s quarterly publications, please contact: [email protected]. How To Give: Contributions and love gifts for the ongoing ministry work and outreaches may be sent by personal check payable to Christian Friends of Israel (see address below or local Representative). We accept the following currencies: US dollars, Canadian dollars, Brit- ish pounds, Euros, and New Israeli Shekels. Please be sure to note all “Where needed most”, “Ministry needs” and undesig- nated gifts as “FOR JERUSALEM” if giving in your nation. Mail checks to : CFI, PO Box 1813, Jerusalem 9101701, ISRAEL. Dear CFI Family, Automatic Deposits: Wire Transfer Information: Over the last matter of months, there has been Israel Discount Bank, 15 Kanfei Nesharim (Branch # 331), much violence in the Gaza region. -

Parshat Chukat July 15-16, 2016 10 Tammuz 5776

CONGREGATION BETH AARON ANNOUNCEMENTS Parshat Chukat July 15-16, 2016 10 Tammuz 5776 SHABBAT TIMES This week’s announcements are sponsored by Lamdeinu. For information on their schedule of classes, see page 4 and go to lamdeinu.org. Friday, July 15 Study in depth; be inspired! Plag Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 6:40 p.m. Earliest Candles: 6:57 p.m. Mincha/Early Shabbat: 7:00 p.m. SCHEDULE FOR THE WEEK OF JULY 17 Latest Candles: 8:08 p.m. Sun Mon Tues Wed Thu Fri Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 8:10 p.m. 17 18 19 20 21 22 Shabbat, July 16 Earliest Tallit 4:40 4:41 4:41 4:42 4:43 4:44 Hashkama Minyan: 7:30 a.m. Shacharit 6:30 MS 5:40 SH 5:55 SH 5:55 SH 5:40 SH 5:55 SH Main Minyan: 8:45 a.m. 7:15 MS 6:20 BM 6:30 BM 6:30 BM 6:20 BM 6:30 BM Sof Zman Kriat Shema: 9:20 a.m. 8:00 MS 7:15 BM 7:15 BM 7:15 BM 7:15 BM 7:15 BM Early Mincha: 1:45 p.m. 8:45 MS 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM Daf Yomi: 6:50 p.m. Mincha 1:45 BM Women’s Learning: 6:50 p.m., at the Greenberg home, 291 Schley Place, Mincha/ 8:05 MS 8:05 MS 8:05 BM 8:05 BM 8:05 BM 6:35 BM an overview to Shoftim Maariv 7:00 MS Meir Hirsch’s shiur: 7:00 p.m. -

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld March 2017 • Purim 5777 A Special Edition in Honor of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Chag HaSemikhah 5777 CELEBRATING THE NEXT GENERATION OF RABBINIC LEADERS Dedicated in loving memory of Phyllis Pollack לע״נ פעשא יטא בת יהודה ז״ל by Dr. Meir and Deborah Pollack Aliza, Racheli, Atara, Yoni, Ilana and Ari 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Purim 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander, Vice President for University and Community Life, Yeshiva University Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Menachem Penner, Max and Marion Grill Dean, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Rabbi Robert Shur, Series Editor Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Content Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2016 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 419, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.0074 This publication contains words of Torah. -

Course Catalog

Course Catalog 2013-2014 תשע”ד Introduction to the Course Catalog eshivat Yesodei HaTorah prides itself on providing Y the finest Torah education available for post high students in Israel. Our goal is to expose each student to essential Torah topics as well as to issues and ideas that are important to him as an individual. Our core curriculum ensures that each talmid will develop the ability to approach any Torah topic with confidence wherever he may be, whether preparing for shiur in Yeshiva University, learning with his chavruta in a secular college, or delivering a shiur at his local shul as a baal habayit. Additionally, our elective courses allow our students to explore a large array of topics that they find to be personally meaningful. In fact, many of these courses were developed specifically at the request of our students. We are most famous for our morning shiurim, during which our students achieve the ability to learn Gemara independently and in depth, while developing a genuine love for learning. Our afternoon and evening shiurim are equally important parts of our broad and holistic curriculum. Our core shiurim, electives, options for independent study, and opportunities to learn one-on-one with rabbeim give our students an unparalleled learning experience. Daily Schedule: Shacharit thru Mincha SHANA ALEPH AND SHANA BET 7:30 Shacharit, Followed by Breakfast 9:00 Morning Seder and Shiur I RABBI KAHN, RABBI ARRAM, RABBI HERCZEG, RABBI KROHN, RABBI LICHTMAN 11:00 Break 11:10 Morning Seder and Shiur II RABBI KAHN, RABBI ARRAM, RABBI -

Christian Friends of Israel Christian

SecondThird Quarter 2018 Jewish Year 5778 “It is too small a thing for you to be my servant to restore the tribes of Jacob and bring back those of Israel I have kept. I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.” Isaiah 49:6 NIV Christian Friends of Israel PO Box 1813 Jerusalem 9101701 ISRAEL Tel: 972-2-6233778 Fax: 972-2-6233913 [email protected] www.cfijerusalem.org For Zion’s Sake A Quarterly Publication / Printed in Israel EDITOR IN CHIEF MANAGING EDITOR / WRITER Stacey Howard Kevin Howard GRAPHIC DESIGNER COPY EDITOR Jennifer Paterniti Coral Mings WRITERS Marcia Brunson, Patricia Cuervo, Maggie Huang, Tiina Karkkainen, Emma Kiser, Olga Kopilova, Jim McKenzie, and Sharon Sanders For Zion’s Sake is published by Christian Friends of Israel’s Jerusalem Office, free of charge to supporters. All articles may be quoted with proper attribution. Reproduction of any content of FZS magazine requires written permission. Direct inquiries to [email protected]. If you wish to help distribute CFI’s quarterly publications, please contact: [email protected]. How To Give: Contributions and love gifts for the ongoing ministry work and outreaches may be sent by personal check payable to Christian Friends of Israel (see address below or local Representative). We accept the following currencies: US dollars, Canadian dollars, Brit- ish pounds, Euros, and New Israeli Shekels. Please be sure to note all “Where needed most”, “Ministry needs” and undesig- nated gifts as “FOR JERUSALEM” if giving in your nation. Mail checks to : CFI, PO Box 1813, Jerusalem 9101701, ISRAEL. -

Attentive Spiritual Leadership SUMMER 2015 - AV 5775

Attentive Spiritual Leadership SUMMER 2015 - AV 5775 Page 2: Beit Hillel News Page 3: The New Sabra: Dignified on the Outside; Tender Within Page 4: Modesty, Dignity and ConversionThe Role of Beit Din in the Immersion of a Woman Page 6: Lest We Pour the Convert Out with the Bathwater: The Risks of Attempting to Improv an Imperfect Status Quo Page 8: Women as Poskot Halacha Page 11: A Community Bar-Mitzvah Celebration for a Child with Cognitive Disabilities1 We are pleased to bring Neuwirth, one of the founders of Beit Hillel, who managed you the latest "Beit Hillel" for three demanding, yet satisfying years. I thank him on publication and update behalf of Beit Hillel members, friends and the board, and I you with our current hope to be able to continue to lead Beit Hillel to the place activities. it strives to be: the center of Israeli Society and the Torah world. Beit Hillel continues with its ongoing unique and Beit Hillel is a leader in realizing the potential of women in historical partnership rabbinical teaching and Halachic ruling, and leads Modern between men and Orthodox Halachic and Ideological thinking in Israel. We women in our Batei are approaching the New Year with ambitions of becoming Hamidrash. We have the main hub for Women in Torah initiatives and for Modern always believed that Orthodox activities in Israel. women should be We believe that Beit Hillel is one of the most important involved in all areas Halacha and Ideology groups in Jewish society today. Our Rabbi Shlomo Hecht of Halacha as equals, members are involved in real life activities and incorporate judged only by their informed and sensible Halachic ruling into the frameworks capability to analyze Halachic, not their gender. -

Sample Viagra Pills

Page 5 Twice Rescued (How Ernest Winter Made it Out) Page 8 Making Your Seder Fun and Kid-Friendly… Page 12 Seder Listings! Page 17 Iran Alive Ministries Page 20 Ebenezer Home in Israel (Pt 1) One Man’s Response… NetFlix Series! Iran Alive! (“Isa” Yeshua in Farsi) An actual bas-relief from Iran where the Site of Suza / Shushan Sits (© Wikimedia) Vol. 30 Number 2 • March / April 2020 • Adar / Nisan / Iyyar 5780-81 • messianictimes.com • Canada/US $5 RPURIM—evival: aJoy M iniR theacle Midst inof UncertaintyRogRess P llsbrook By Cliff Keller by AAron A By Cliff Keller Was Qasem Soleimani’s early two millennia separate astor Lee marveled during the Seder at the recent death a “moment Nthe first Messianic Jews— collective memory of the Jewish people, the followersof liberation?” of Yeshua—from their Pcontinuity of historical identity of the Jewish latter-day peers. people, the “we were slaves in Egypt,” “our Purim is many things to many “They say miracles are past,” fathers,” and “the L-rd took us out with an people and, like most Jewish declared Lafeu, an old L-rd of Ber- outstretched arm.” He appreciated what the Jewish holidays, replete with paradox. tram’s court in Shakespeare’s All’s It is the “classic account of our people had to endure as a family. The celebration of Wellpeople’s that Endsconfrontation Well, but, thoughwith brute it Passover is one of the original festivals that depicts mayanti-Semitism,” not yet be obvious wrote to the some, late the the identity of the nation of Israel. -

TAMMUZ 5774 - Issue 4

Attentive Spiritual Leadership SUMMER 2014 - TAMMUZ 5774 - Issue 4 Page 2 Beit Hillel on the Tumultuous Events of Summer 2014 | Page 3 A Wake-Up Call For Israeli Society| Page 4 P'sak Halacha and All its Implications - The Path of Beit Hillel | Page 5 What Is Religious Zionism? Results Of Comprehensive Survey Regarding Religious Zionist Community | Page 8 Meaningful Military and National Service for Women | Page 11 Torah Perspectives and Halachic Decisions Regarding People with Disabilities | Page 14Women Dancing with a Sefer Torah on Simchat Torah | Page 15 News from Beit Hillel We lovingly dedicate this edition to the memories of Naftali Fraenkel, Gil-Ad Schaer and Eyal Yifrach, HY"D. The Schaers and Fraenkels are active members of the Beit Hillel family, and together with the Yifrachs, allowed all of Am Yisrael to feel as if their boys were ours, as well. Throughout the 18-day ordeal and beyond, the families acted with a level of grace and dignity that elevated the spirits of a demoralized nation when it needed it most. The multitudes of people who visited during the shiv'ah commented that although they went to provide strength to the families, they left feeling that they had been strengthened by the families. These remarkable occurrences are a tribute to the quality of character possessed by each of the parents, and a Kiddush Shem Shamayim that will, B'ezrat Hashem, be a zechut for the neshamot tehorot of our three precious boys. .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה BEIT HILLEL ON THE TUMULTUOUS EVENTS OF THE EARLY SUMMER This summer, Israeli society has experienced several tumultuous chinam’.