Overcoming Challenges in Seed Production of Bonamia Menziesii, a Critically Endangered and Hawai’I-Endemic Vine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recovery Plan for Tyoj5llllt . I-Bland Plants

Recovery Plan for tYOJ5llllt. i-bland Plants RECOVERY PLAN FOR MULTI-ISLAND PLANTS Published by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: Date: / / As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most ofour nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values ofour national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests ofall our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island Territories under U.S. administration. DISCLAIMER PAGE Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Costs indicated for task implementation and/or time for achievement ofrecovery are only estimates and are subject to change. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, otherthan the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position ofthe U.S. -

Sato Hawii 0085O 10652.Pdf

RESTORATION OF HAWAIIAN TROPICAL DRY FORESTS: A BIOCULTURAL APPROACH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BOTANY (CONSERVATION BIOLOGY) MAY 2020 By Aimee Y. Sato Thesis Committee: Tamara Ticktin, Chairperson Christian P. Giardina Rakan A. Zahawi Kewords: Tropical Dry Forest, Biocultural, Conservation, Restoration, Natural Regeneration, Social-Ecological 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my graduate committee for steering and guiding me through my thesis work. Dr. Tamara Ticktin, my thesis advisor who has been the greatest kumu (teacher) that I could have asked for in my research. I also thank my two committee members, Dr. Rakan A. Zahawi and Dr. Christian P. Giardina, who both brought their expansive levels of expertise to help develop this thesis. Thank you so much to the hoaʻāina (caretakers/restoration managers) of my two project sites. I thank the hoaʻāina of Kaʻūpūlehu, ‘Aunty’ Yvonne Carter, ‘Uncle’ Keoki Carter, Wilds Brawner, Kekaulike Tomich, Lehua Alapai, Kuʻulei Keakealani, and ‘Aunty’ Hannah Kihalani Springer. Thank you to the hoaʻāina of Auwahi, Art Medeiros, Erica von-Allmen, Ainoa and Kalaʻau Kaiaokamalie, Amy Campbell, Andy Bieber, Robert Pitts, and Kailie Aina. I would also like to acknowledge Kamehameha Schools and the Ulupalakua Ranch for allowing me to conduct this research on their lands. Thank you to the dry forest restoration managers and researchers that participated in the overview survey of Hawaiian dry forests. On Oʻahu Island: Lorena ‘Tap’ Wada, James Harmon and Kapua Kawelo. On Hawaiʻi Island: Elliott Parsons, Rebecca Most, Lena Schnell, Kalā Asing, Jen Lawson, and Susan Cordell. -

Comparative Biology of Seed Dormancy-Break and Germination in Convolvulaceae (Asterids, Solanales)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jayasuriya, Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan, "COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY- BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES)" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 639. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) ABSRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Art and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Lexington, Kentucky Co-Directors: Dr. Jerry M. Baskin, Professor of Biology Dr. Carol C. Baskin, Professor of Biology and of Plant and Soil Sciences Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Gehan Jayasuriya 2008 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) The biology of seed dormancy and germination of 46 species representing 11 of the 12 tribes in Convolvulaceae were compared in laboratory (mostly), field and greenhouse experiments. -

*Wagner Et Al. --Intro

NUMBER 60, 58 pages 15 September 1999 BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS HAWAIIAN VASCULAR PLANTS AT RISK: 1999 WARREN L. WAGNER, MARIE M. BRUEGMANN, DERRAL M. HERBST, AND JOEL Q.C. LAU BISHOP MUSEUM PRESS HONOLULU Printed on recycled paper Cover illustration: Lobelia gloria-montis Rock, an endemic lobeliad from Maui. [From Wagner et al., 1990, Manual of flowering plants of Hawai‘i, pl. 57.] A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1998 Research publications of Bishop Museum are issued irregularly in the RESEARCH following active series: • Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. A series of short papers PUBLICATIONS OF describing original research in the natural and cultural sciences. Publications containing larger, monographic works are issued in BISHOP MUSEUM four areas: • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology Numbering by volume of Occasional Papers ceased with volume 31. Each Occasional Paper now has its own individual number starting with Number 32. Each paper is separately paginated. The Museum also publishes Bishop Museum Technical Reports, a series containing information relative to scholarly research and collections activities. Issue is authorized by the Museum’s Scientific Publications Committee, but manuscripts do not necessarily receive peer review and are not intended as formal publications. Institutions and individuals may subscribe to any of the above or pur- chase separate publications from Bishop Museum Press, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA. Phone: (808) 848-4135; fax: (808) 841-8968; email: [email protected]. Institutional libraries interested in exchanging publications should write to: Library Exchange Program, Bishop Museum Library, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA; fax: (808) 848-4133; email: [email protected]. -

Kapunakea Long Range Management Plan 2016-2021

Kapunakea Preserve, West Maui, Hawaiʻi Final Long-Range Management Plan Fiscal Years 2016-2021 Submitted to the Department of Land & Natural Resources Natural Area Partnership Program Submitted by The Nature Conservancy – Hawai‘i Operating Unit April 2015 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 ANNUAL DELIVERABLES SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 5 RESOURCE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................... 7 General Setting ................................................................................................................................ 7 Flora and Fauna................................................................................................................................ 7 MANAGEMENT.............................................................................................................................................. 8 Management Considerations........................................................................................................... 8 Management Units ..................................................................................................................................... 14 Management Programs ............................................................................................................................. -

TAXON:Hyptis Pectinata

TAXON: Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. SCORE: 14.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. Family: Lamiaceae Common Name(s): comb hyptis Synonym(s): Mesosphaerum pectinatum (L.) Kuntze Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 21 Mar 2016 WRA Score: 14.0 Designation: H(Hawai'i) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Aromatic Herb, Crop Weed, Environmental Weed, Unpalatable, Small-Seeded Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 y 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans y=1, n=0 n 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle Tolerates a wide range of soil conditions (or limestone 410 y=1, n=0 y conditions if not a volcanic island) Creation Date: 22 Mar 2016 (Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit.) Page 1 of 16 TAXON: Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. -

Santalum Freycinetianum Var. Lanaiense Lanai Sandalwood (‘Iliahi)

Santalum freycinetianum var. lanaiense Lanai sandalwood (‘iliahi) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Santalum freycinetianum var. lanaiense / Lanai sandalwood (‘iliahi) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................................... 3 1.1 Reviewers .......................................................................................................................3 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review:................................................................. 3 1.3 Background: .................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS........................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Application of the 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) policy......................... 5 2.2 Recovery Criteria.......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status .................................................... 7 2.4 Synthesis.......................................................................................................................14 3.0 RESULTS .........................................................................................................................16 3.1 Recommended Classification:................................................................................... -

What Is the Evidence That Invasive Species Are a Significant Contributor to the Decline Or Loss of Threatened Species? Philip D

Invasive Species Systematic Review, March 2015 What is the evidence that invasive species are a significant contributor to the decline or loss of threatened species? Philip D. Roberts, Hilda Diaz-Soltero, David J. Hemming, Martin J. Parr, Richard H. Shaw, Nicola Wakefield, Holly J. Wright, Arne B.R. Witt www.cabi.org KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................. 1 Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 3 Keywords ................................................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................................................ 4 Background .............................................................................................................................. 5 Objective of the review ............................................................................................................ 7 The primary review question: ....................................................................................... 7 Secondary question 1: ................................................................................................. 7 Secondary question 2: ................................................................................................. 7 Methods -

Department of the Interior

Vol. 77 Monday, No. 112 June 11, 2012 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Listing 38 Species on Molokai, Lanai, and Maui as Endangered and Designating Critical Habitat on Molokai, Lanai, Maui, and Kahoolawe for 135 Species; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 21:18 Jun 08, 2012 Jkt 226001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\11JNP2.SGM 11JNP2 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with PROPOSALS6 34464 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 112 / Monday, June 11, 2012 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR writing, at the address shown in the FOR • Reaffirm the listing for two listed FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT section plants with taxonomic changes. Fish and Wildlife Service by July 26, 2012. • Designate critical habitat for 37 of ADDRESSES: You may submit comments the 38 proposed species and for the two 50 CFR Part 17 by one of the following methods: listed plants with taxonomic changes. • • Revise designated critical habitat [Docket No. FWS–R1–ES–2011–0098; MO Federal eRulemaking Portal: http:// 92210–0–0009] www.regulations.gov. Search for FWS– for 85 listed plants. R1–ES–2011–0098, which is the docket • Designate critical habitat for 11 RIN 1018–AX14 number for this proposed rule. listed plants and animals that do not • U.S. mail or hand delivery: Public have designated critical habitat on these Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Comments Processing, Attn: FWS–R1– islands. and Plants; Listing 38 Species on ES–2011–0098; Division of Policy and One or more of the 38 proposed Molokai, Lanai, and Maui as Directives Management; U.S. -

2009-02-23-MA-FEA-Kapunakea

Final Environmental Assessment Kapunakea Preserve West Maui, Natural Area Partnership Program In accordance with Chapter 343, Hawai‘i Revised Statues Proposed by the State of Hawaii Department of Land & Natural Resources The Nature Conservancy – Hawai‘i Operating Unit January 2009 Kapunakea Final EA 2009 CONTENTS I. SUMMARY.......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Project Name................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Proposing Agency / Applicant...................................................................................................................................... 4 Approving Agency........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Anticipated Determination............................................................................................................................................ 4 Project Location............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Agencies Consulted during EA Preparation ................................................................................................................. 4 Federal................................................................................................................................................................ -

Conserving North America's Threatened Plants

Conserving North America’s Threatened Plants Progress report on Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving North America’s Threatened Plants Progress report on Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Andrea Kramer, Abby Hird, Kirsty Shaw, Michael Dosmann, and Ray Mims January 2011 Recommended ciTaTion: Kramer, A., A. Hird, K. Shaw, M. Dosmann, and R. Mims. 2011. Conserving North America’s Threatened Plants: Progress report on Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation . BoTanic Gardens ConservaTion InTernaTional U.S. Published by BoTanic Gardens ConservaTion InTernaTional U.S. 1000 Lake Cook Road Glencoe, IL 60022 USA www.bgci.org/usa Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Contents Acknowledgements . .3 Foreword . .4 Executive Summary . .5 Chapter 1. The North American Flora . .6 1.1 North America’s plant diversity . .7 1.2 Threats to North America’s plant diversity . .7 1.3 Conservation status and protection of North America’s plants . .8 1.3.1 Regional conservaTion sTaTus and naTional proTecTion . .9 1.3.2 Global conservaTion sTaTus and proTecTion . .10 1.4 Integrated plant conservation . .11 1.4.1 In situ conservaTion . .11 1.4.2 Ex situ collecTions and conservaTion applicaTions . .12 1.4.3 ParameTers of ex situ collecTions for conservaTion . .16 1.5 Global perspective and work on ex situ conservation . .18 1.5.1 Global STraTegy for PlanT ConservaTion, TargeT 8 . .18 Chapter 2. North American Collections Assessment . .19 2.1 Background . .19 2.2 Methodology . .19 2.2.1 Compiling lisTs of ThreaTened NorTh American Taxa . -

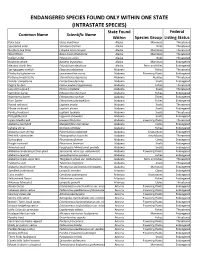

Endangered Species Only Found in One State

ENDANGERED SPECIES FOUND ONLY WITHIN ONE STATE (INTRASTATE SPECIES) State Found Federal Common Name Scientific Name Within Species Group Listing Status Polar bear Ursus maritimus Alaska Mammals Threatened Spectacled eider Somateria fischeri Alaska Birds Threatened Northern Sea Otter Enhydra lutris kenyoni Alaska Mammals Threatened Wood Bison Bison bison athabascae Alaska Mammals Threatened Steller's Eider Polysticta stelleri Alaska Birds Threatened Bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus Alaska Mammals Endangered Aleutian shield fern Polystichum aleuticum Alaska Ferns and Allies Endangered Spring pygmy sunfish Elassoma alabamae Alabama Fishes Threatened Fleshy‐fruit gladecress Leavenworthia crassa Alabama Flowering Plants Endangered Flattened musk turtle Sternotherus depressus Alabama Reptiles Threatened Slender campeloma Campeloma decampi Alabama Snails Endangered Pygmy Sculpin Cottus paulus (=pygmaeus) Alabama Fishes Threatened Lacy elimia (snail) Elimia crenatella Alabama Snails Threatened Vermilion darter Etheostoma chermocki Alabama Fishes Endangered Watercress darter Etheostoma nuchale Alabama Fishes Endangered Rush Darter Etheostoma phytophilum Alabama Fishes Endangered Round rocksnail Leptoxis ampla Alabama Snails Threatened Plicate rocksnail Leptoxis plicata Alabama Snails Endangered Painted rocksnail Leptoxis taeniata Alabama Snails Threatened Flat pebblesnail Lepyrium showalteri Alabama Snails Endangered Lyrate bladderpod Lesquerella lyrata Alabama Flowering Plants Threatened Alabama pearlshell Margaritifera marrianae Alabama Clams