Interview with Michael Shakman IS-A-L-2008-009 February 14, 2008 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

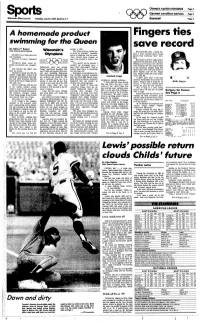

Swimming for the Queen Save Record by Andrew P

Olympic cyclist reinstated Page 2 Spoils Ganassi condition serious Page 2 Wisconsin State Journal Tuesday, July 24,1984, Section 2 • Baseball Page 3 A homemade product Fingers ties swimming for the Queen save record By Andrew P. Baggot Wisconsin's tember of 1979. State Journal sports reporter "My father always wanted me MILWAUKEE (AP) - Rollie Fin- to swim for England," Annabelle gers is more worried about saving •She didn't say a thing about tea Olympians said in a telephone visit last week. games than collecting "save" num- and crumpets. "He's always been English at bers. Princess Di wasn't mentioned heart and wanted to keep it that Milwaukee's veteran right-hander at all. way. registered his 23rd save of the season Liverpool's latest soccer tri- "If it weren't for my parents, I Monday in a 6-4 victory over the New umph was passed over complete- wouldn't be swimming here, I York Yankees. The save was his 216th ly. Parliament were not among know that," said added. "They've in the American League, tying him And, horrors, she didn't even Cripps' uppermost thoughts. She always been there to encourage with former New York and Texas re- have an accent. was 11 then, just another all-Amer- me and help me." liever Sparky Lyle for the league Chances are good, too, that An- ican girl, attending Edgewood Expensive encouragement, too. lead. Fingers holds the major-league nabelle Cripps didn't curtsy at all School in Madison and doing things The monthly overseas telephone Annabelle Cripps mark with 324. -

Peter J. Birnbaum President and Chief Executive Officer

PETER J. BIRNBAUM PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Peter Birnbaum has served as President and Chief Executive Officer of Attorneys’ Title Guaranty Fund, Inc. (ATG) since 1991. Under his leadership, the company has developed into a leading lawyer service organization with annual revenues in excess of $100 million. In 2015, Peter received the Justice John Paul Stevens Award for those who exemplify the Justice’s commitment to integrity and public service in the practice of law. In 2014, Peter was proud to receive the Illinois Bar Foundation Distinguished Award for Excellence. In 2011, Birnbaum was also inducted as a Laureate in the Academy of Illinois Lawyers, the highest honor bestowed by the Illinois State Bar Association. In 2013 he received the Chicago Bar Association Vanguard Award for promoting diversity in the profession. Also, in 2005, he received the Abraham Lincoln Marovitz Lend A Hand Foundation “Making a Difference” award. Birnbaum holds or has held leadership positions on several corporate and philanthropic boards. He served as president of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Metropolitan Chicago. Birnbaum is currently President of the Jesse White Foundation. He led the effort to build the Jesse White Community Center, a state of the art athletic and community center on the site of former Cabrini Green high rise. It opened in the Fall of 2014. A past president of the Alumni Board and current Board of Overseers member of the Chicago-Kent College of Law, Birnbaum was honored with a Distinguished Service Award from the College in 2004. In addition, in 2013 he was named one of Chicago-Kent College of Law’s 125 Alumni of Distinction of its 125 year history for his outstanding professional and community service achievements. -

In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016)

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2016 In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016) Douglas G. Baird Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Douglas G. Baird, "In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016)", 83 University of Chicago Law Review 1723 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 83 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1717 2016 Provided by: The University of Chicago D'Angelo Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Apr 7 12:52:01 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information The University of Chicago Law Review Volume 83 Fall 2016 Number 4 D 2016 by The University of Chicago IN MEMORIAM: ABNER J. MIKVA (1926-2016) Kenneth L. Adamst I first met Abner Mikva in May 1970, when he was a forty- four-year-old freshman congressman representing Hyde Park, Woodlawn, and South Shore. President Richard Nixon had just announced the invasion of Cambodia, and campuses all over the country were in an uproar, including Kent State University, where the National Guard shot and killed four students during a protest. -

In the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois County Department, Criminal Division

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CRIMINAL DIVISION ) ) ) IN RE APPOINTMENT OF SPECIAL PROSECUTOR ) No. 2001 Misc. # 4 ) ) ) PETITION FOR APPOINTMENT OF A SPECIAL PROSECUTOR The Petitioners, Lawrence E. Kennon, Mary D. Powers, and Mary L. Johnson, all three of whom are citizens of Illinois and residents of Cook County, together with Citizens Alert, the Coalition to End Police Torture and Brutality, First Defense Legal Aid, the Justice Coalition of Greater Chicago, the Cook County Bar Association, the Chicago Council of Lawyers, the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Inc., the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, the Illinois Coalition Against the Death Penalty, the Illinois Death Penalty Moratorium Project, the National Lawyers Guild, Amnesty International, and Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, by their attorneys, Randolph N. Stone, of the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School, and Locke E. Bowman, of the MacArthur Justice Center, respectfully request that this Court appoint a special prosecutor to investigate allegations of torture, perjury, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and other offenses by police officers under the command of Jon Burge at Area 2 and later Area 3 headquarters in the City of Chicago during the period from 1973 to the present. In support, petitioners state: 1. During the period from 1973 to 1991, at least sixty-six individuals claimed that they 1 were tortured while in the custody of Jon Burge, or police officers under his command at Area 2 Police Headquarters and later Area 3 Police Headquarters in the City of Chicago. -

Guide to the Philip M. Klutznick Papers 1914-1999

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Philip M. Klutznick Papers 1914-1999 © 2004 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 6 Related Resources 8 Subject Headings 8 INVENTORY 9 Series I: Family and Biographical, 1914-1992 9 Series II: General Files, 1938-1990 15 Subseries 1: Early files, 1938-1946 17 Subseries 2: Business and Development files, 1950-1990 19 Subseries 3: Chicago files, 1975-1989 25 Subseries 4: Israel and the Middle East, 1960-1990 28 Subseries 5: Department of Commerce, 1979-1989 31 Subseries 6: Subject files, 1950-1990 32 Series III: Correspondence, 1946-1999 37 Subseries 1: Chronological Correspondence, 1983-1991 38 Subseries 2: General Correspondence, 1946-1993 41 Series IV: Organizations, 1939-1992 188 Subseries 1: B'nai B'rith, 1939-1990 190 Subseries 2: World Jewish Congress, 1971-1989 200 Subseries 3: Other Organizations, 1960-1992 212 Series V: Speeches and Writings, 1924-1992 257 Series VI: Clippings, Oversize and Audio/Visual, 1924-1999 291 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.KLUTZNICK Title Klutznick, Philip M. Papers Date 1914-1999 Size 175.5 linear ft. (306 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Philip M. Klutznick, businessman, philanthropist, diplomat, government official and Jewish leader. The Philip M. Klutznick Papers comprise 175.5 linear feet and include correspondence, manuscripts, notes, published materials, photographs, scrapbooks, architectural plans, awards and mementos and audio and video recordings. -

Law Clerks: a Jurisprudential Lens

Please do not remove this page Law clerks: a jurisprudential lens. Dane, Perry https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12663159710004646?l#13663159700004646 Dane, P. (2020). Law clerks: a jurisprudential lens. George Washington Law Review Arguendo, 88, 54–82. https://doi.org/10.7282/00000104 Document Version: Version of Record (VoR) Published Version: https://www.gwlr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/88-Geo.-Wash.-L.-Rev.-Arguendo-54.pdf This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/26 14:04:02 -0400 Law Clerks: A Jurisprudential Lens Perry Dane* INTRODUCTION 2019 was the putative hundredth anniversary of the formal institution of Supreme Court law clerks.1 It is understandable at this milestone to focus on biography, history, and warm personal reminiscences. As a former clerk to Justice William J. Brennan Jr., memories of my time with him remain sharply etched and deeply meaningful.2 My concern in this Essay is more abstract, however. My aim is to use the simple fact that law clerks (not just Supreme Court law clerks) often draft opinions as a lens through which to reflect on several jurisprudential issues, including the institutional structures of each of the three branches of our government, the nature of the judicial function, and the interpretation of judicial and other legal texts. Along the way, I also propose some tentative conclusions about the legitimacy and hermeneutical relevance of the law clerk’s role. -

Circuit Rider Vol 10.Pdf

April 2011 Featured In This Issue Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole TheThe A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between CirCircuitcuit Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole The 2009 Amendments to Rule 15(a)- Fundamental Changes and Potential Pitfalls for Federal Practitioners, By Katherine A. Winchester and Jessica Benson Cox Object Now or Forever Hold Your Peace or The Unhappy Consequences on Appeal of Not Objecting in the District Court to a Magistrate Judge’s Decision, By Jeffrey Cole RiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH Some Advice on How Not to Argue a Case in the Seventh Circuit — Unless . You’re My Rider Adversary, By Brian J. Paul C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Certification and Its Discontents: Rule 23 and the Role of Daubert, By Catherine A. Bernard Recent Changes to Rules Governing Amicus Curiae Disclosures, By Jeff Bowen C h a n g e s The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . ... 2-5 A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . 6-23 Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper . 24-29 The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole . -

Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT)

TORTURE IN THE HOMELAND: Failure of the United States to Implement the International Convention against Torture to protect the human rights of African- American Boys and African-American Men in Chicago, Illinois A Response to the fifth periodic report filed by The United States of America. The United States’ review will take place in Geneva on November 12 and 13, 2014. Submitted by: National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL) Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT) Contact Info: Stan Willis (312) 750-1950 or [email protected] Sali Vickie Casanova Willis, [email protected] Endorsed by the following organizations and individuals: Mothers & Their Torture Victim Sons: Jeanette Plummer (Johnny Plummer); Glades James Daniel (Erwin Daniels); Almeater Maxson (Mark Maxson); Armanda Shackelford (Gerald Reed); Shirley Burgess (Wilbur Driver); Bertha Escamilla (Nick Escamilla); Sara Ortiz (William Netron); Anabel Perez (Jaime Hauad); Mary L. Johnson (Michael Johnson). Torture Victims/Survivors: Fabian Pico; Anthony Sims; Tyrone Reyna; Enrique Valdez; Eric Gomez; Oscar Gomez; Abel Quinones; Daniel Taylor; George Anderson; William Ephraim; Rudy Davilla; Clayborn Smith; Keith Walker; David Turner; Kilroy Watkins; Alphonso Pinex; Keith Eric Johnson; Nick Escamilla; Derrick Flewellen; Antoine Anderson; Donell Edwards; Joseph Jackson; Michael Carter; Andre Brown; Sean Tyler; Malik Taylor; Tron Williams; Miguel Morales; Gregory Logan; Antonio Nicholas; Johnathan Tolliver; Enrique Valdez; Xavier Catron; Jerry Gillespie; James De Avila; Tyrone -

INTRODUCTION NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSI1Y LEGAL CLINIC News & Notes

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSI1Y LEGAL CLINIC News & Notes March 1991 INTRODUCTION This year the Clinic enrolled more students than ever in its casework and classroom components. Student interest in supervised practice is stimulated by the importance of the legal work that the Clinic does and by the variety of casework experience which the Clinic offers. Students in the Clinic work on behalf of children and their families seeking special education benefits, they represent children in Juvenile Court, and counsel and represent foster parents who are not receiving the benefits to which they are entitled from the Department of Children and Family Services. This year, the Clinic has taken an increasing number of domestic relations cases in which there are contested custody issues. The Clinic is also active in the representation of condemned prisoners. There is also exciting news from the classroom side. The interest in our trial advocacy and lawyering process courses continues to grow. Work on the integration of trial advocacy and ·evidence continues. In response to student demand, a course in poverty law was taught by Clinic faculty this year for the first time since 1974. The Clinical Fellows program, supported in large part by alumni donations, has been particularly successful this year. Our two Clinical Fellows, Julie Nice, '86, and Bruce Boyer, '86 have been outstanding casework supervisors and classroom teachers. Bruce taught in the trial practice-lawyering process sequence. Julie organized and taught the poverty law course. After two years as a Clinical Fellow, Julie Nice will join the University of Denver Law School's faculty where she will continue her work in clinical education. -

FY 2002 & 2003 Annual Report

THE CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION 2002 & 2003 ANNUAL REPORT h TOGETHER we are MAKING A DIFFERENCE 321 SOUTH PLYMOUTH COURT, 3RD FLOOR, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60604 PHONE: (312) 554-1204 ~ FAX: (312) 554-1203 ~ WEB SITE: WWW. CHICAGOBARFOUNDATION. ORG OUR MISSION the chicago bar foundation, the charitable arm of the chicago TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT 2 bar association, improves access to justice for people who are WHO WE ARE AND WHO WE HELP 3 impacted by poverty, abuse, and discrimination. HIGHLIGHTS FROM FY 2002 AND 2003 4 our mission is grounded in the belief that access to justice is HOW WE HELP central to our democratic society and that the concerted Supporting Legal Aid Organizations 7 efforts of a few can make a real improvement in the lives Our Grants 8 Organizational Support Grants 9 of many. Projects/Emerging Issues Grants 13 we accomplish our mission by awarding grants and other assistance Special Grants 14 to legal aid and public interest organizations, encouraging the Leadership, Resources and Assistance 15 Helping Ensure a New Generation of Legal Aid Lawyers 16 legal community to contribute time and money, functioning as a Promoting Pro Bono 17 clearinghouse for information and resources, and providing Increasing Access to the Court System For the Public 20 leadership in the community on access to justice issues. Promoting Broader Community Support for Access to Justice 21 HOW YOU HELP The Many Ways that Thousands Support the CBF 25 The Abraham Lincoln Circle of Justice 26 Life Fellows of the CBF 27 Our Many Law Firm and Corporate Supporters 30 OUR FINANCIAL STRENGTH 32 OUR YOUNG PROFESSIONALS BOARD 34 OUR LEND A HAND PROGRAM 36 OUR BOARD AND STAFF 38 FRIENDS, Thanks to your generous support, THE established the Leonard Jay Schrager who we are THE CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION improves access to justice for people CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION completed another Award. -

60Th-Anniversary-Boo

HORATIO ALGER ASSOCIATION of DISTINGUISHED AMERICANS, INC. A SIXTY-YEAR HISTORY Ad Astra Per Aspera – To the Stars Through Difficulties 1947 – 2007 Craig R. Barrett James A. Patterson Louise Herrington Ornelas James R. Moffett Leslie T. Welsh* Thomas J. Brokaw Delford M. Smith Darrell Royal John C. Portman, Jr. Benjy F. Brooks* Jenny Craig Linda G. Alvarado Henry B. Tippie John V. Roach Robert C. Byrd Sid Craig Wesley E. Cantrell Herbert F. Boeckmann, II Kenny Rogers Gerald R. Ford, Jr. Craig Hall John H. Dasburg Jerry E. Dempsey Art Buchwald Paul Harvey Clarence Otis, Jr. Archie W. Dunham Joe L. Dudley, Sr. S. Truett Cathy Thomas W. Landry* Richard M. Rosenberg Bill Greehey Ruth Fertel* Robert H. Dedman* Ruth B. Love David M. Rubenstein Chuck Hagel Quincy Jones Julius W. Erving J. Paul Lyet* Howard Schultz James V. Kimsey Dee J. Kelly Daniel K. Inouye John H. McConnell Roger T. Staubach Marvin A. Pomerantz John Pappajohn Jean Nidetch Fred W. O’Green* Christ Thomas Sullivan Franklin D. Raines Don Shula Carl R. Pohlad Willie Stargell* Kenneth Eugene Behring Stephen C. Schott Monroe E. Trout D.B. Reinhart* Henry Viscardi, Jr.* Doris K. Christopher Philip Anschutz Dennis R. Washington Robert H. Schuller William P. Clements, Jr. Peter M. Dawkins Carol Bartz Joe L. Allbritton Romeo J. Ventres John B. Connally, Esq.* J. R. “Rick” Hendrick, III Arthur A. Ciocca Walter Anderson Carol Burnett Nicholas D’Agostino* Richard O. Jacobson Thomas C. Cundy Dwayne O. Andreas Trammell Crow Helen M. Gray* Harold F. “Gerry” Lenfest William J. Dor Dorothy L. Brown Robert J. -

Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules

ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON BANKRUPTCY RULES September 21-22, 2000 Harriman, New York ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON BANKRUPTCY RULES Meeting of September 21-22, 2000 Arden Conference Center, Harriman, NY Agenda Introductory Items 1. Approval of minutes of March 2000 meeting. 2. Report on the June 2000 meeting of the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure (Standing Committee). 3. Report on the June 2000 meeting of the Committee on the Administration of the Bankruptcy System. 4. Status of "bankruptcy reform" bills. Action Items 5. Proposed amendments to Rule 2016 to make the rule applicable to non-attorney bankruptcy petition preparers. 6. Proposed amendment to Rule 8014 concerning taxation of costs in an appeal. 7. Report of the Forms Subcommittee: a) Proposed amendment to Official Form 15, Order Confirming Plan, to conform to the proposed amendments to Rule 3020 concerning injunctions contained in a plan that have been published for comment; b) Request for guidance concerning whether the subcommittee should undertake a general review of the official forms at this time. 8. Report of the Subcommittee on Privacy and Public Access. Consideration of privacy issues and possible amendments to the rules [e.g., Rule 1005] and official forms to reduce Internet exposure of personal information. 9. Report of the Subcommittee on Attorney Conduct, Including Rule 2014 Disclosure Requirements proposing a new Rule 7007.1 and conforming amendment to Rule 9014 requiring disclosure of financial interests by parties in adversary proceedings and contested matters. 10. Proposed amendments to Rule 3015(d) to de-link from the notice of a chapter 13 confirmation hearing the duty to provide a copy of the plan or a summary of the plan, and to require the debtor to provide a copy of the plan directly to the standing trustee and to each creditor.