Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming for the Queen Save Record by Andrew P

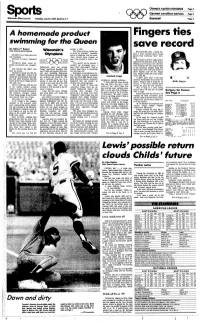

Olympic cyclist reinstated Page 2 Spoils Ganassi condition serious Page 2 Wisconsin State Journal Tuesday, July 24,1984, Section 2 • Baseball Page 3 A homemade product Fingers ties swimming for the Queen save record By Andrew P. Baggot Wisconsin's tember of 1979. State Journal sports reporter "My father always wanted me MILWAUKEE (AP) - Rollie Fin- to swim for England," Annabelle gers is more worried about saving •She didn't say a thing about tea Olympians said in a telephone visit last week. games than collecting "save" num- and crumpets. "He's always been English at bers. Princess Di wasn't mentioned heart and wanted to keep it that Milwaukee's veteran right-hander at all. way. registered his 23rd save of the season Liverpool's latest soccer tri- "If it weren't for my parents, I Monday in a 6-4 victory over the New umph was passed over complete- wouldn't be swimming here, I York Yankees. The save was his 216th ly. Parliament were not among know that," said added. "They've in the American League, tying him And, horrors, she didn't even Cripps' uppermost thoughts. She always been there to encourage with former New York and Texas re- have an accent. was 11 then, just another all-Amer- me and help me." liever Sparky Lyle for the league Chances are good, too, that An- ican girl, attending Edgewood Expensive encouragement, too. lead. Fingers holds the major-league nabelle Cripps didn't curtsy at all School in Madison and doing things The monthly overseas telephone Annabelle Cripps mark with 324. -

In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016)

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2016 In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016) Douglas G. Baird Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Douglas G. Baird, "In Memoriam: Abner J. Mikva (1926-2016)", 83 University of Chicago Law Review 1723 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 83 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1717 2016 Provided by: The University of Chicago D'Angelo Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Apr 7 12:52:01 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information The University of Chicago Law Review Volume 83 Fall 2016 Number 4 D 2016 by The University of Chicago IN MEMORIAM: ABNER J. MIKVA (1926-2016) Kenneth L. Adamst I first met Abner Mikva in May 1970, when he was a forty- four-year-old freshman congressman representing Hyde Park, Woodlawn, and South Shore. President Richard Nixon had just announced the invasion of Cambodia, and campuses all over the country were in an uproar, including Kent State University, where the National Guard shot and killed four students during a protest. -

In the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois County Department, Criminal Division

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CRIMINAL DIVISION ) ) ) IN RE APPOINTMENT OF SPECIAL PROSECUTOR ) No. 2001 Misc. # 4 ) ) ) PETITION FOR APPOINTMENT OF A SPECIAL PROSECUTOR The Petitioners, Lawrence E. Kennon, Mary D. Powers, and Mary L. Johnson, all three of whom are citizens of Illinois and residents of Cook County, together with Citizens Alert, the Coalition to End Police Torture and Brutality, First Defense Legal Aid, the Justice Coalition of Greater Chicago, the Cook County Bar Association, the Chicago Council of Lawyers, the Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Inc., the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, the Illinois Coalition Against the Death Penalty, the Illinois Death Penalty Moratorium Project, the National Lawyers Guild, Amnesty International, and Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, by their attorneys, Randolph N. Stone, of the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School, and Locke E. Bowman, of the MacArthur Justice Center, respectfully request that this Court appoint a special prosecutor to investigate allegations of torture, perjury, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and other offenses by police officers under the command of Jon Burge at Area 2 and later Area 3 headquarters in the City of Chicago during the period from 1973 to the present. In support, petitioners state: 1. During the period from 1973 to 1991, at least sixty-six individuals claimed that they 1 were tortured while in the custody of Jon Burge, or police officers under his command at Area 2 Police Headquarters and later Area 3 Police Headquarters in the City of Chicago. -

Law Clerks: a Jurisprudential Lens

Please do not remove this page Law clerks: a jurisprudential lens. Dane, Perry https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12663159710004646?l#13663159700004646 Dane, P. (2020). Law clerks: a jurisprudential lens. George Washington Law Review Arguendo, 88, 54–82. https://doi.org/10.7282/00000104 Document Version: Version of Record (VoR) Published Version: https://www.gwlr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/88-Geo.-Wash.-L.-Rev.-Arguendo-54.pdf This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/26 14:04:02 -0400 Law Clerks: A Jurisprudential Lens Perry Dane* INTRODUCTION 2019 was the putative hundredth anniversary of the formal institution of Supreme Court law clerks.1 It is understandable at this milestone to focus on biography, history, and warm personal reminiscences. As a former clerk to Justice William J. Brennan Jr., memories of my time with him remain sharply etched and deeply meaningful.2 My concern in this Essay is more abstract, however. My aim is to use the simple fact that law clerks (not just Supreme Court law clerks) often draft opinions as a lens through which to reflect on several jurisprudential issues, including the institutional structures of each of the three branches of our government, the nature of the judicial function, and the interpretation of judicial and other legal texts. Along the way, I also propose some tentative conclusions about the legitimacy and hermeneutical relevance of the law clerk’s role. -

Circuit Rider Vol 10.Pdf

April 2011 Featured In This Issue Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole TheThe A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between CirCircuitcuit Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole The 2009 Amendments to Rule 15(a)- Fundamental Changes and Potential Pitfalls for Federal Practitioners, By Katherine A. Winchester and Jessica Benson Cox Object Now or Forever Hold Your Peace or The Unhappy Consequences on Appeal of Not Objecting in the District Court to a Magistrate Judge’s Decision, By Jeffrey Cole RiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH Some Advice on How Not to Argue a Case in the Seventh Circuit — Unless . You’re My Rider Adversary, By Brian J. Paul C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Certification and Its Discontents: Rule 23 and the Role of Daubert, By Catherine A. Bernard Recent Changes to Rules Governing Amicus Curiae Disclosures, By Jeff Bowen C h a n g e s The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 Jerold S. Solovy: In Memoriam, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . ... 2-5 A Celebration of 35 Years of Judicial Service: Collins Fitzpatrick’s Interview of Judge John Grady, Introduction By Jeffrey Cole . 6-23 Great Expectations Meet Painful Realities (Part I), By Steven J. Harper . 24-29 The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26: Limitations on Discovery of Communications Between Lawyers and Experts, By Jeffrey Cole . -

Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT)

TORTURE IN THE HOMELAND: Failure of the United States to Implement the International Convention against Torture to protect the human rights of African- American Boys and African-American Men in Chicago, Illinois A Response to the fifth periodic report filed by The United States of America. The United States’ review will take place in Geneva on November 12 and 13, 2014. Submitted by: National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL) Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT) Contact Info: Stan Willis (312) 750-1950 or [email protected] Sali Vickie Casanova Willis, [email protected] Endorsed by the following organizations and individuals: Mothers & Their Torture Victim Sons: Jeanette Plummer (Johnny Plummer); Glades James Daniel (Erwin Daniels); Almeater Maxson (Mark Maxson); Armanda Shackelford (Gerald Reed); Shirley Burgess (Wilbur Driver); Bertha Escamilla (Nick Escamilla); Sara Ortiz (William Netron); Anabel Perez (Jaime Hauad); Mary L. Johnson (Michael Johnson). Torture Victims/Survivors: Fabian Pico; Anthony Sims; Tyrone Reyna; Enrique Valdez; Eric Gomez; Oscar Gomez; Abel Quinones; Daniel Taylor; George Anderson; William Ephraim; Rudy Davilla; Clayborn Smith; Keith Walker; David Turner; Kilroy Watkins; Alphonso Pinex; Keith Eric Johnson; Nick Escamilla; Derrick Flewellen; Antoine Anderson; Donell Edwards; Joseph Jackson; Michael Carter; Andre Brown; Sean Tyler; Malik Taylor; Tron Williams; Miguel Morales; Gregory Logan; Antonio Nicholas; Johnathan Tolliver; Enrique Valdez; Xavier Catron; Jerry Gillespie; James De Avila; Tyrone -

INTRODUCTION NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSI1Y LEGAL CLINIC News & Notes

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSI1Y LEGAL CLINIC News & Notes March 1991 INTRODUCTION This year the Clinic enrolled more students than ever in its casework and classroom components. Student interest in supervised practice is stimulated by the importance of the legal work that the Clinic does and by the variety of casework experience which the Clinic offers. Students in the Clinic work on behalf of children and their families seeking special education benefits, they represent children in Juvenile Court, and counsel and represent foster parents who are not receiving the benefits to which they are entitled from the Department of Children and Family Services. This year, the Clinic has taken an increasing number of domestic relations cases in which there are contested custody issues. The Clinic is also active in the representation of condemned prisoners. There is also exciting news from the classroom side. The interest in our trial advocacy and lawyering process courses continues to grow. Work on the integration of trial advocacy and ·evidence continues. In response to student demand, a course in poverty law was taught by Clinic faculty this year for the first time since 1974. The Clinical Fellows program, supported in large part by alumni donations, has been particularly successful this year. Our two Clinical Fellows, Julie Nice, '86, and Bruce Boyer, '86 have been outstanding casework supervisors and classroom teachers. Bruce taught in the trial practice-lawyering process sequence. Julie organized and taught the poverty law course. After two years as a Clinical Fellow, Julie Nice will join the University of Denver Law School's faculty where she will continue her work in clinical education. -

FY 2002 & 2003 Annual Report

THE CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION 2002 & 2003 ANNUAL REPORT h TOGETHER we are MAKING A DIFFERENCE 321 SOUTH PLYMOUTH COURT, 3RD FLOOR, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60604 PHONE: (312) 554-1204 ~ FAX: (312) 554-1203 ~ WEB SITE: WWW. CHICAGOBARFOUNDATION. ORG OUR MISSION the chicago bar foundation, the charitable arm of the chicago TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT 2 bar association, improves access to justice for people who are WHO WE ARE AND WHO WE HELP 3 impacted by poverty, abuse, and discrimination. HIGHLIGHTS FROM FY 2002 AND 2003 4 our mission is grounded in the belief that access to justice is HOW WE HELP central to our democratic society and that the concerted Supporting Legal Aid Organizations 7 efforts of a few can make a real improvement in the lives Our Grants 8 Organizational Support Grants 9 of many. Projects/Emerging Issues Grants 13 we accomplish our mission by awarding grants and other assistance Special Grants 14 to legal aid and public interest organizations, encouraging the Leadership, Resources and Assistance 15 Helping Ensure a New Generation of Legal Aid Lawyers 16 legal community to contribute time and money, functioning as a Promoting Pro Bono 17 clearinghouse for information and resources, and providing Increasing Access to the Court System For the Public 20 leadership in the community on access to justice issues. Promoting Broader Community Support for Access to Justice 21 HOW YOU HELP The Many Ways that Thousands Support the CBF 25 The Abraham Lincoln Circle of Justice 26 Life Fellows of the CBF 27 Our Many Law Firm and Corporate Supporters 30 OUR FINANCIAL STRENGTH 32 OUR YOUNG PROFESSIONALS BOARD 34 OUR LEND A HAND PROGRAM 36 OUR BOARD AND STAFF 38 FRIENDS, Thanks to your generous support, THE established the Leonard Jay Schrager who we are THE CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION improves access to justice for people CHICAGO BAR FOUNDATION completed another Award. -

Testimonial Privileges and the Federal Rules of Evidence Kenneth S

Hastings Law Journal Volume 53 | Issue 4 Article 2 1-2002 Giving Codification a Second Chance--Testimonial Privileges and the Federal Rules of Evidence Kenneth S. Broun Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth S. Broun, Giving Codification a Second Chance--Testimonial Privileges and the Federal Rules of Evidence, 53 Hastings L.J. 769 (2002). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol53/iss4/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Giving Codification a Second Chance- Testimonial Privileges and the Federal Rules of Evidence by KENNETH S. BROUN* The testimonial privilege rules in the Proposed Rules of Evidence submitted to Congress by the United States Supreme Court in 1972 almost doomed the total project. The presence of those rules became a rallying point for general opposition to the entire proposal and a symbol for all that was perceived to be wrong with the rules as a whole Not only was the substance of the proposed privilege rules vigorously attacked by scholars, practitioners, judges and members of Congress, the idea that the federal law of privilege should be codified was rejected by many.2 Many academics and practicing lawyers preferred an uncodified federal law of privilege, and, in particular, one that relied upon state privilege law. There was especially widespread criticism of a federal law of privilege insofar as it would govern diversity cases.' In the fallout that followed the submission of the Proposed Rules, what emerged was a set of evidence rules that included no codification of rules on testimonial privilege. -

The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation

THE FELLOWS OF THE AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION 2011 Chair 2011-2012 Doreen D. Dodson Chair – Elect Myles V. Lynk Secretary Don Slesnick The Fellows is an honorary organization of attorneys, judges and law professors whose profes- sional, public and private careers have demonstrated outstanding dedication to the welfare of their communities and to the highest principles of the legal profession. Established in 1955, The Fellows encourage and support the research program of the American Bar Foundation. The American Bar Foundation works to advance justice through research on law, legal institutions, and legal processes. Current research covers such topics as end-of-life decision making, the value of early childhood education, how lawyers in public interest law organizations conceptualize and pursue their goals, what people think of the civil justice system against the backdrop of the politics of tort reform and the changes in the law that have resulted from the tort reform movement, and the factors that play a psychological role in laypersons’ decisions about justice and responsibility. The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, 4th Floor Chicago, IL 60611 (800) 292-5065 Fax: (312) 988-6579 [email protected] www.americanbarfoundation.org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS OF THE OFFICERS OF THE FELLOWS, CONT’D AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION Don Slesnick, Secretary William C. Hubbard, President Slesnick & Casey LLP Hon. Bernice B. Donald, Vice President 2701 Ponce De Leon Boulevard, Suite 200 David A. Collins, Treasurer Coral Gables, FL 33134-6041 Ellen J. Flannery, Secretary Office: (305) 448-5672 Robert L. Nelson, ABF Director Fax: (305) 448-5685 Susan Frelich Appleton [email protected] Mortimer M. -

Interview with Michael Shakman IS-A-L-2008-009 February 14, 2008 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Michael Shakman IS-A-L-2008-009 February 14, 2008 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 DePue: Today is Thursday the 14th of February, 2008. My name is Mark DePue. I'm the Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. I'm here today with Mr. Michael Shakman, a lawyer and—how should I put this?—the plaintiff in what ended up being the Shakman Decree, which has had, in some people's measure, at least, a revolutionary impact on the nature of the way politics is conducted in Chicago and in Cook County. So this is one I've been looking forward to for a long time, Mr. Shakman. Thank you very much for taking time out of your busy schedule to talk with us today. Shakman: You are welcome. DePue: I should mention that we're in his offices, and if you could mention the business where you work. Shakman: We're a law firm, and its name is Miller, Shakman, and Beam. DePue: How long have you been with this firm? Shakman: I've been with this law firm or its predecessor law firms since October of 1967. -

Lessons in Democracy from the Jury Box

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 23 Issues 1&2 2018 Batson for Judges, Police Officers &eachers: T Lessons in Democracy From the Jury Box Stacy L. Hawkins Rutgers Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Courts Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Stacy L. Hawkins, Batson for Judges, Police Officers &eachers: T Lessons in Democracy From the Jury Box, 23 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2018). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol23/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATSON FOR JUDGES, POLICE OFFICERS & TEACHERS: LESSONS IN DEMOCRACY FROM THE JURY BOX Stacy L. Hawkins* In our representative democracy we guarantee equal participation for all, but we fall short of this promise in so many domains of our civic life. From the schoolhouse, to the jailhouse, to the courthouse, racial minorities are under- represented among key public decision-makers, such as judges, police officers, and teachers. This gap between our aspirations for representative democracy and the reality that our judges, police officers, and teachers are often woefully under-repre- sentative of the racially diverse communities they serve leaves many citizens of color wanting for the democratic guarantee of equal participation.