Noble Hill Rosenwald School: a Community Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Rosenwald Schools on Black Student Achievement

THE IMPACT OF ROSENWALD SCHOOLS ON BLACK ACHIEVEMENT Daniel Aaronson Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Bhashkar Mazumder Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago June 2010 Abstract: The Black-White gap in completed schooling among Southern born men narrowed sharply between the World Wars after being stagnant for cohorts born between 1880 and 1910. We examine a large scale school construction project, the Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative, which was designed to improve the educational opportunities for Southern rural Blacks. From 1914 to 1931, nearly 5,000 school buildings were constructed, serving approximately 36 percent of the Black rural school-aged Southern population by 1930. We use historical Census data and World War II enlistment records to analyze the effects of the program on school attendance, literacy, high school completion, years of schooling, earnings, hourly wages, and migration. We find that the Rosenwald program accounts for at least 30 percent of the sizable educational gains of Southern Blacks born during the 1910s and 1920s. Using scores on the Army General Classification Test (AGCT), a precursor to the AFQT, we also find that access to the schools significantly improved cognitive skills. In the longer run, exposure to the schools raised the wages of Blacks who remained in the South relative to Whites in the South by about 35 percent, implying a private rate of return to a year of additional schooling of about 17 percent. Moreover, Rosenwald significantly increased northbound migration of young adult Blacks, likely fueling further income gains. Across all outcomes, the improvements were highest in counties with the lowest levels of Black school attendance suggesting that schooling treatments can have a very large impact among those with limited access to education. -

The Campaign to Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald

The Campaign To Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Historic Context Inventory & Analysis October 2018 2 Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools NHP Campaign The Campaign To Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Historic Context Inventory & Analysis October 2018 Prepared by: EHT TRACERIES, INC. 440 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 Laura Harris Hughes, Principal Bill Marzella, Project Manager John Gentry, Architectural Historian October 2018 3 Dedication This report is dedicated to the National Parks and Conservation Association and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for their unwavering support of and assistance to the Rosenwald Park Campaign in its mission to establish a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park. It is also dedicated to the State Historic Preservation Officers and experts in fifteen states who work so tirelessly to preserve the legacy of the Rosenwald Schools and who recommended the fifty-five Rosenwald Schools and one teacher’s home to the Campaign for possible inclusion in the proposed park. Cover Photos: Julius Rosenwald, provided by the Rosenwald Park Campaign; early Rosenwald School in Alabama, Architect Magazine; St. Paul’s Chapel School, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; Sandy Grove School in Burleson County, Texas, 1923, Texas Almanac. Rear Cover Photos: Interior of Ridgeley Rosenwald School, Maryland. Photo by Tom Lassiter, Longleaf Productions; Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald documentary. 4 Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools NHP Campaign Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Julius Rosenwald’s Life and Philanthropy 10 Biography of Julius Rosenwald 10 Rosenwald’s Philanthropic Activities 16 Rosenwald’s Approach to Philanthropy 24 Significance of Julius Rosenwald 26 African American Education and the Rosenwald Schools Program 26 African American Education in the Rural South 26 Booker T. -

Rosenwald Teaching Guide

Film and Bonus Features Teaching Guide This guide for the Rosenwald film and bonus features is available for free use by teachers, professors, after school program directors, and anyone else who chooses to use the lessons to introduce the film and bonus features to students. It is designed for use by middle school, high school, college, and teacher education. Copies can be made for individual classroom use. Reprint requests for use beyond the classroom should be submitted to the Ciesla Foundation. © Ciesla Foundation, 2018 The guide was produced with funding from the Righteous Persons Foundation. Teaching for Change produced the lessons for the Ciesla Foundation. The lessons are by Pete Fredlake and the design by Mykella Palmer. Editorial assistance provided by Lianna C. Bright, Thalia Ertman, Aviva Kempner, Alison Richards, and Athena Robles for the Ciesla Foundation. This educational guide is intended for use with the Rosenwald DVD. To purchase the DVD, go to www.rosenwaldfilm.org. TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 4 Viewing Guide 8 A Community of Learners: Creating a Classroom Vision Statement 26 Seeking Refuge: Connecting the Dots from 1933 to Today 34 “Social Justice Everywhere!” Rabbi Emil Hirsch and Rosenwald's Philanthropy 41 The Great Migration 46 Structured Academic Controversy: Freedom for Education, Education for Freedom 55 Meet and Greet the Rosenwald Fellows 64 Bonus Features for Classroom Use 87 Glossary 94 Additional Resources 96 OVERVIEW Students pose at the Rosenwald Pee Dee Colored School, South Carolina. In an act of defiance against the racist culture of Jim Crow — state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States from the late 19th century until 1965 — a prominent American Jewish businessman named Julius Rosenwald partnered with African American leaders and communities in the South to build more than 5,300 schools and buildings that supported the ed- ucation of more than 660,000 African American children. -

Historic Resources of the Rosenwald School Building Program in South

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. __X__ New Submission ____ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing The Rosenwald School Building Program in South Carolina, 1917-1932 B. Associated Historic Contexts The Rosenwald School Building Program in South Carolina, 1917-1932 C. Form Prepared By Name/title: Lindsay C. M. Weathers Organization: University of South Carolina Public History Program Date: 3 December 2008 Street & number: Gambrell Hall, University of South Carolina Telephone: (803) 315-0626 City or town: Columbia State: SC Zip code: 29208 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (___ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature and title of certifying official _________________________________________________________________________________________ Elizabeth M. -

The Rosenwald Plan: Architecture for Education Nancy Rohr

T hree D o llars Volume XXVII, No. 4 WINTER 2001 T h e H is t o r ic H u n t s v il l e Q u a r t e r l y of L ocal A rchitecture and Preservation T h e R o s e n w a l d P l a n : A rchitecture f o r E d u c a t io n HISTORIC HUNTSVILLE FOUNDATION Founded 1974 Officers for 2000-2001 Walter Kelley..........................................................................Chairman Richard Van Valkenburgh.............................................Vice Chairman Martha M iller........................................................................... Secretary Sarah Hereford.........................................................................Treasurer Buzz Heeschen (immediate past Chairman)......................ex officio Staff Lynne Lowery.........................................................Executive Director Heather A. Cross.........................................................Quarterly Editor Board Members Kay Anderson Martha Miller Escoe Beatty Sol Miller Ollye Conley Rod Moak Freeda Darnell Nancy Munson Bobby DeNeefe Nancy Orr Billie Grosser Gerald Patterson Margaret Anne Hanaw Dale Rhoades Buzz Heeschen Jorie Rieves Sarah Hereford Randy Roper Mike Holbrook Jim Roundtree Lynn Jones Stephanie Sherman Karol Kapustka Guy Spencer, Jr. Sarah Lauren Kattos Wenona Switzer Walter Kelley Malcolm Tarkington Jim Maples Steve Templeton Cathy McNeal Richard Van Valkenburgh Cover: Plan and perspective of a Rosenwald One-Room Community School from Samuel Smith's booklet, Community School Plans, circa 1920. ISSN 1074-567X The H istoric H untsville Q uarterly o r L o c a l A rchitecture a n d P reservation Volume XXVII, No. 4 Winter 2001 T h e R o s e n w a l d P l a n : A rchitecture f o r E d u c a t io n Table of Contents From the Editor: Heather A. -

Tennessee in the Era of Jim Crow Teacher Packet

Tennessee in the Era of Jim Crow Table of Contents Pages 1. Content Essay 2-5 2. Student Activity 6-7 Tennessee in the Era of Jim Crow Essential Question: How did W.E.B. DuBois, James Napier and Mary Church Terrell respond to Jim Crow? With the end of Reconstruction, AfricanAmericans saw the rights they had gained through the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments disappear once Federal troops were withdrawn from the South. In Tennessee, the story was somewhat different. Because Tennessee was not part of the military reconstruction in the South, African- American men had never gained the same political power that they held in states such as Mississippi during Reconstruction. However, African American men were not completely stripped of their voting rights when Reconstruction ended because Republicans and sometimes urban Democrats used African American votes to ensure victory for their candidates or issues. This gave African Americans in Tennessee leverage to negotiate better treatment in the era of Jim Crow. Tennessee passed its first Jim Crow law in 1875. Jim Crow laws legalized segregation of African Americans and whites. The laws were named after a character from a popular traveling show in the late 1800’s. The Jim Crow character, played by a white actor in blackface makeup, portrayed African Americans as stupid, brutish, and completely inferior to whites. The 1875 law, Chapter 130 of the Acts of Tennessee, allowed discrimination in hotels, trains, theaters, and most other public places. Under the law, business owners could simply refuse service to anyone they chose. If a patron complained, he or she could be fined up to one hundred dollars. -

Dunbar Rosenwald School Loudon, Tennessee Heritage

DUNBAR ROSENWALD SCHOOL LOUDON, TENNESSEE HERITAGE DEVELOPMENT PLAN MTSU CENTER FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Fall 2018 Prepared by Savannah Grandey, Fieldwork Coordinator Victoria Hensley, Graduate Assistant Tiffany Momon, Research Professor Carroll Van West, Director CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 3 WHY THE DUNBAR ROSENWALD SCHOOL MATTERS. 4 PRESERVATION NEEDS OF THE BUILDING. .. 7 POTENTIAL PARTNERSHIPS. 17 ADDITIONAL FUNDING SOURCES . 20 APPENDIX. 25 2 Introduction In 2007, the Center for Historic Preservation worked with the community in Loudon, Tennessee, to nominate the Dunbar Rosenwald School on Steekee Street to the National Register of Historic Places. Since the nomination, the community used the historic school for various functions but ten years later the building needs renovations and repair. In the late summer of 2018 Ms. Joyce Fields of the Dunbar Rosenwald Foundation contacted the Center regarding appropriate restoration and repair methods. A few weeks later, on September 6, 2018, community members, local government officials, and the Dunbar Rosenwald Foundation met with Center fieldwork coordinator Savannah Grandey, graduate assistant Victoria Hensley, research professor Tiffany Momon, and Center Director Dr. Carroll Van West at the school. They discussed goals and opportunities. Community members recalled activities and important events associated with the school. The meeting ended with a request that the Center prepare a Heritage Development Plan, which would help the Foundation and local officials move forward on restoration and the needed partnerships to ensure that this historic property survives as a vital community heritage asset for generations to come. 3 Why the Dunbar Rosenwald School Building Matters The Dunbar Rosenwald School in Loudon, Loudon County, Tennessee, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its local historical significance in education, social history, and African American ethnic heritage. -

Black Community Building in the Virginia Tidewater, 1865 to the Post-1954 Era

No Longer Lost at Sea: Black Community Building In the Virginia Tidewater, 1865 to the post-1954 Era Hollis Earl Pruitt Gloucester County, Virginia Bachelor of Arts, University of Arkansas at Little Rock 1979 Master of Arts, University of Tennessee at Knoxville 1991 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary May 2013 UMI Number: 3574204 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Di!ss0?t&iori Publishing UMI 3574204 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Copyright © 2013 by Hollis Earl Pruitt APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved^ the Committee, March, 2013 Professor Michael L. Blakey, National Endowment for the Humanities College of William and Mary ‘ Professor Grey Gundaker Duane A. and Virginia S. Dittman Professor of American Studies and Anthropology College of William and Mary /?Q6jx (^<^k\ V y ro fesso r Kimberly Phillips Dean of Brooklyn Colleges School of Humanities and Social Sciences (J Professor M. -

The Rosenwald Schools and Black Education in NC

The Rosenwald Schools and Black Education in North Carolina By THOMAS W. HANCHETT* Originally published in North Carolina Historical Review volume LXV, number 4 (October 1988), 387 – 444. This on-line edition published November 24, 2014: www.historysouth.org Today the structures stand almost forgotten, scattered across the North Carolina countryside. Some are now houses, businesses, or barns. Others -- particularly those that stand next to churches as community halls -- still retain the large banks of windows that mark them as school buildings. These are Rosenwald Fund schools, landmarks in the history of African American education. Conceived in the 1910s by black educator Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee Institute staff, the Rosenwald program represented a massive effort to improve black rural schooling in the South through public-private partnership. The name came from philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Rosenwald offered matching grants to rural communities interested in building black schools.1 Washington and Rosenwald hoped not only to improve black school facilities but also to promote black-white cooperation in those dark days of Jim Crow and spur southern localities to increase support for black education. * Mr. Hanchett is a doctoral student in history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The author wishes to thank Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Dr. Nell Irvin Painter, and Dr. George Brown Tindall for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. *When this article first appeared in 1988, Tom Hanchett was a doctoral student in history at UNC Chapel Hill. He thanks Dr. Dan L. Morrill, Dr. -

The History, Architecture, and Preservation of Rosenwald Schools in Georgia

THE HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE, AND PRESERVATION OF ROSENWALD SCHOOLS IN GEORGIA by SUMMER ANNE CIOMEK (Under the Direction of Mark Reinberger, Ph.D.) ABSTRACT Through the collaboration of a pioneer of African American education and a staunch businessman, six rural, African American schools were constructed in Alabama in 1914, financed with matching grants. The success of this experiment marked the beginning of the fruitful partnership between Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald. It was also the modest beginning of the Julius Rosenwald Fund, an African American educational philanthropy that was responsible for aiding in the construction of over 5,000 schools in fifteen states in the southern United States. The Rosenwald Fund quickly became a leader in the field of African American education as well as an innovator of rural schoolhouse design. This thesis recounts the history of the Rosenwald Fund, those responsible for its establishment and its school-building program, and the evolution of rural school design and its subsequent standardization. This thesis also examines three case studies of Rosenwald schools in Georgia that were successfully preserved, restored, and reused by community members and former students. Finally, a synopsis of efforts in the state of Georgia to find and protect these schools is presented as well as steps for preserving and reusing Rosenwald schools. INDEX WORDS: African American education, Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, school architecture, historic preservation THE HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE, AND PRESERVATION OF ROSENWALD SCHOOLS IN GEORGIA by SUMMER ANNE CIOMEK A.B., University of Georgia, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Summer Anne Ciomek All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE, AND PRESERVATION OF ROSENWALD SCHOOLS IN GEORGIA by SUMMER ANNE CIOMEK Major Professor: Mark Reinberger, Ph.D. -

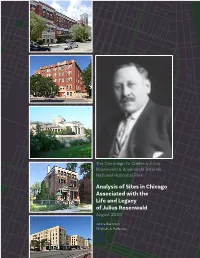

Analysis of Sites in Chicago Associated with Julius Rosenwald

The Campaign to Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Analysis of Sites in Chicago Associated with the Life and Legacy of Julius Rosenwald August 2020 Julia S. Bachrach Elizabeth A. Patterson 1 Cover Illustrations Left side, top to bottom: Sears, Roebuck & Company Administration Building, photo by Julia S. Bachrach Wabash Avenue YMCA, photo by Julia S. Bachrach Museum of Science and Industry, photo by Julia S. Bachrach South Side Community Art Center, photo by Dennis McClendon Rosenwald Courts, photo by Dennis McClendon Right side: Julius Rosenwald, photo from Notable Men 2 of Chicago and Their City, 1910 Contents 5 Executive Summary 7 Introduction 8 Sites Considered 9 Map of Chicago Sites Considered 11 Sears, Roebuck & Company Administration Building 19 Wabash Avenue YMCA 25 Museum of Science and Industry 33 Rosenwald Courts 39 South Side Community Art Center 45 Rosenwald Home 47 Conclusion 49 Bibliography Design layout and map by Dennis McClendon, Chicago CartoGraphics ©Julia S. Bachrach, Elizabeth A. Patterson, and the Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Campaign, 2020 3 Dedication This report is dedicated to the National Parks Conservation Association and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for their continuing steadfast support of and assistance to the Rosenwald Park Campaign in its mission to create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald 4 Schools National Historical Park. Executive Summary Founded in 2016, the Rosenwald Park Campaign seeks to honor and preserve the important contributions to American history by businessman and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald. The Campaign proposes the development of a multi-site National Historical Park with a small number of Rosenwald Schools in various locations and a visitor center in Rosenwald’s home city of Chicago. -

The Greatest 20Th-Century Donor You've Never Heard Of

EXCELLENCE IN PHILANTHROPY PHILANTHROPIC FREEDOM DONOR INTENT EVENTS WHO K-12 ECONOMIC ALLIANCE FOR ANNUAL VETERANS WE ARE EDUCATION OPPORTUNITY CHARITABLE REFORM MEETING ARTICLES ABOUT ALMANAC Home > Donor Intent > The Greatest 20th-century Donor Youve Never Heard Of > DONOR INTENT The Greatest 20th-Century Donor You’ve Never Interview with Christopher Heard Of Oechsli The president of Atlantic Julius Rosenwald built up black schools and spent down his endowment. Philanthropies reflects on Chuck Feeney’s legendary Cover Story from May / June 2006 issue of Philanthropy magazine generosity, and how to By Martin Morse Wooster recover donor intent. Four Brothers and the Apocalypse A biography of the Koch family Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of offers a fascinating window The Almanac into their life and philanthropy. Black Education in the American South of American By Peter M. Ascoli Philanthropy 409 pp., $35, Indiana University Press Benefits of a Gift Gone A compendium of the Great Wrong Donors, Great Achievements, Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932) was one of the twentieth century’s greatest Great Ideas, and Latest Facts philanthropists, but he’s little known today. He should not remain obscure. His Princeton’s failure led the Robertsons’ son Bill and his on private giving in the U.S. efforts to build thousands of schools for blacks in the South enabled a great many siblings to make an even black children to receive a better education than they would otherwise have had. greater gift—to the whole And his impassioned arguments against perpetual foundations raise questions that country.