Papers on Parliament Number 66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Legislative Assembly Election (PDF, 3.7MB)

The Hon K Purick MLA Speaker Northern Territory Legislative Assembly Parliament House Darwin NT 0800 Madam Speaker In accordance with Section 313 of the Electoral Act, I am pleased to provide a report on the conduct of the 2012 Northern Territory Legislative Assembly General Elections. The Electoral Act requires this report to be tabled in the Legislative Assembly within three sittings days after its receipt. Additional copies have been provided for this purpose. Bill Shepheard Electoral Commissioner 24 April 2014 ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER’S FOREWORD The 2012 Legislative Assembly General Elections (LAGE) were the third general elections to be conducted under the NT Electoral Act 2004 (NTEA). The 2012 LAGE was also conducted under the substantially revised NTEA which had a significant impact on operational processes and planning arrangements. Set term elections were provided for in 2009, along with a one-day extension to the election timeframe. Further amendments with operational implications received assent in December 2011 and were in place for the August 2012 elections. A number of these changes were prescribed for both the local government and parliamentary electoral framework and, to some extent, brought the legislation into a more contemporary operating context and also aligned its features with those of other jurisdictions. The NTEC workload before the 2012 LAGE was particularly challenging. It was the second major electoral event conducted by the NTEC within the space of a few months. Local government general elections for five municipalities and ten shire councils were conducted on 24 March 2012, the first time their elections had all been held on the same day. -

DJ Playlist.Djp

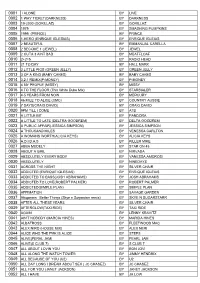

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

Report on the Conduct of the 2007 Federal Election and Matters Related Thereto

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Report on the conduct of the 2007 federal election and matters related thereto Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters June 2009 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-0-642-79156-6 (Printed version) ISBN 978-0-642-79157-3 (HTML version) Chair’s foreword The publication of this report into the conduct of the 2007 federal election marks 25 years since the implementation of major reforms to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 which were implemented by the Commonwealth Electoral Legislation Act 1983 and came into effect for the 1984 federal election. These reforms included changes to redistribution processes, the implementation of public funding of election campaigns and the establishment of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC). This report continues the tradition of examining and reporting on the conduct of federal elections and relevant legislation which has been carried out by the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters and its predecessor, the Joint Select Committee on Electoral Reform. Federal elections in Australia are remarkably complex logistical events. The 2007 election was the largest electoral event undertaken in Australia’s history, with 13,646,539 electors on the electoral roll, to whom 13,364,359 sets of ballot papers were issued, with some 12,930,814 actually being counted in House of Representatives Elections. Australian citizens enjoy a fundamental right to vote which has its basis in sections 7 and 24 of the Constitution. It is evident, however, that at least 466,794 electors were unable to exercise the franchise correctly at the 2007 election, either because they were not on the electoral roll, or they were on the roll with incomplete or incorrect details. -

638 EC Report

Elections in the 21st Century: from paper ballot to e-voting The Independent Commission on Alternative Voting Methods Elections in the 21st Century: from paper ballot to e-voting The Independent Commission on Alternative Voting Methods Elections in the 21st Century: from paper ballot to e-voting Membership of the Independent Commission on Alternative Voting Methods Dr Stephen Coleman (Chair), Director of the The Commission was established by the Electoral Hansard Society’s e-democracy programme, and Reform Society, and is grateful to them for lecturer in Media and Citizenship at the London hosting our meetings. School of Economics & Political Science The Electoral Reform Society is very grateful to Peter Facey, Director of the New Politics the members of the Independent Commission for Network the time which they have so freely given and for their commitment to the development of good Paul Gribble CBE, Independent consultant and electoral practices in the UK.The Society, which advisor on Election Law to the Conservative has since 1884 been campaigning for the Party; Editor of Schofield’s Election Law strengthening of democracy (although principally through reform of the voting system), believes Steven Lake, Director (Policy & External Affairs) that the Commission’s report is a major of the Association of Electoral Administrators, and contribution to the debate on the modernisation Electoral Registration Officer for South of the way we vote and that the report should Oxfordshire District Council guide the development of policy and practice -

![PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8157/party-listening-music-by-tune-3628157.webp)

PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]

[ PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ] 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 22 STEPS by Damien Leith 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A HARD RAIN'S A - GONNA FALL by Bryan Ferry And Roxy Music A LITTLE TOO LATE by Delta Goodrem {Karaoke} A NEW DAY HAS COME by Celine Dion {Karaoke} A PUBLIC AFFAIR by Jessica Simpson A THOUSAND MILES by Vanessa Carlton {Karaoke} A TOWN CALLED MALICE by The Jam ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE by Counting Crows {Karaoke} ADDICTED by Simple Plan {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO BASS by Puretone ADDICTED TO LOVE by Robert Palmer {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO YOU by Anthony Callea {Karaoke} ADVERTISING SPACE by Robbie Williams AIN'T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH by Jimmy Barnes ALL FOR YOU by Janet Jackson ALL I NEED IS YOU by Guy Sabastian {Karaoke} ALL I WANNA DO by Jo Jo Zep And The Falcons ALL I WANNA DO by Sheryl Crow {Karaoke} ALL MY LOVE by Led Zeppelin ALL NIGHT by Janet Jackson ALL NIGHT LONG by Lionel Richie ALL RIGHT NOW by Free {Karaoke} ALL SEATS TAKEN by Bec Cartright ALL THAT SHE WANTS by Ace Of Base {Karaoke} ALRIGHT by Supergrass ALWAYS BE WITH YOU by Human Nature AMAZING by Alex Lloyd {Karaoke} AMAZING by George Michael AMERICAN PIE by Don Mc Lean {Karaoke} AMERICAN PIE by Madonna AND SHE WAS by Talking Heads ANGEL by Amanda Perez {Karaoke} ANGEL by Shaggy {Karaoke} ANGEL EYES by Paulini {Karaoke} ANGELS BROUGHT ME HERE by Guy Sebastian {Karaoke} ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL by Pink Floyd {Karaoke} ANOTHER CHANCE by Roger Sanchez {Karaoke} -

The Sweet Taste of Forgiveness Catalog No

PENINSULA BIBLE CHURCH CUPERTINO THE SWEET TASTE OF FORGIVENESS Catalog No. 930 Luke 7:36-50 SERIES: PARABLES OF THE KINGDOM Sixth Message John Hanneman January 2, 1994 As we enter 1994 we return to a series of messages which we began and when she learned that He was reclining at the table in the last summer on the parables of Jesus from the gospel of Luke. We Pharisee’s house, she brought an alabaster vial of perfume, and will immerse ourselves once more in these marvelous, mysterious standing behind Him at His feet, weeping, she began to wet His texts which formed such a critical part of Jesus’ teaching ministry to feet with her tears, and kept wiping them with the hair of her his disciples. Our text today is Luke 7:36-50, the parable of the two head, and kissing His feet, and anointing them with the per- debtors. fume. Now when the Pharisee who had invited Him saw this, I want to begin this morning by quoting from a 1960’s song by he said to himself, “If this man were a prophet He would know Simon and Garfunkel. It is a rather short song but it is one that is who and what sort of person this woman is who is touching long on sadness: Him, that she is a sinner.” Time it was and what a time it was, And Jesus answered and said to him, “Simon, I have something It was…a time of innocence, a time of confidences. to say to you.” And he replied, “Say it, Teacher.” “A certain mon- Long ago…it must be…I have a photograph, eylender had two debtors: one owed five hundred denarii, and Preserve your memories, they’re all that’s left you. -

Singers News

Singers News Volume 3 Issue 8 August 2006 11612 S Western MAKE MONE Y WHILE GETTING DRUNK! Clarkson, Ain’t No Other Man by Christina Chicago, IL 60643 Stop in Beverly Records and pick up Aguilera, Crazy by Gnarls Barkley, Deja Vu by your free copy of Karaoke Nightlife. This 773-779-0066 Beyonce, Me & U by Cassie, Stars Are blind by publication lists hundreds of clubs that Paris Hilton, A Public Affair, by Jessica Simpson, have Karaoke Nights, many of these clubs Torn by Letoya, Do It To It by Cherish, So Sick offer cash prizes for best singers, some by Ne-Yo, Dani California by Red Hot Chili even give prizes for worst singer! Peppers, Let U Go by Ashley Parker Angel, Top 10 Beverly Records You High by James Blunt, Some Hearts by Carrie 1. Gnarls Barkley - Crazy PHM0906 Underwood, Over my Head by Fray, and What’s 2. Big & Rich - 8th of November CDSD0145 DID YOU KNOW? Left of Me by Nick Lachey. 3. Jewel - Good Day CDSD4609 Soundchoice offers custom made cds 4. Fergie - London Bridge PHM 1006 for only $5.00 per song! We have a couple new discs on Zoom, including 5. Dashboard Confessional - Don’t Wait CDSD4609 Beverly Records and Soundchoice have teamed 6. Black Eyed Peas - My Humps PSG1650 up for this unique service, compile your own a great rockabilly one from the early hits of 7. Jessica Simpson - A Public Affair CDSD4609 Johnny Cash. The instrumentation is fantastic! 8. James Blunt - You’re Beautiful THGP0604 karaoke disc using the Soundchoice catalog 9. -

Media All Jessica, All the Time Lacey Rose, 10.06.06, 8:30 AM ET If You're a Jessica Simpson Fan, You May Be Headed to the Theat

Media All Jessica, All The Time Lacey Rose, 10.06.06, 8:30 AM ET If you're a Jessica Simpson fan, you may be headed to the theaters this weekend to see her in Employee of the Month. But if you can't make it to Lionsgate's new movie, fear not: You can catch Simpson's song stylings on her new album, A Public Affair. Or you can find her at the newsstand--the 26-year-old is currently on the cover of Allure, but she's certain to be on the front of US Weekly, People or Star sometime soon. You can also buy her new line of "Hair U Wear" wigs. Or her "Dessert Beauty" line of edible "bath and body" treats. It's no secret that the old scarcity model of celebrity culture--regular people only got a glimpse of famous people, which made them want to see them that much more--vanished sometime in the CompuServe era. You can get as much access to Simpson and a slew of other instant stars as you want, whenever you want it. But if the customer is always right, Simpson and her ilk may be taking the wrong approach-- apparently you can get too much of a good thing. According to Encino, Calif.-based E-Poll Market Research, which ranks more than 2,800 celebrities on 46 different personality attributes, Simpson’s "overexposed" score went from 17% in September 2003 to 41% in mid-2006. (The average for most celebrities at the peak of their careers is between 3% and 7%.) During that same period, Simpson’s “talented” score dropped from 36% to a disappointing 28%. -

Search the Works

{ } = word or expression can't be understood {word} = hard to understand, might be this [Opening remarks missing] ... we have laid down in this course. It is not true that the truth has to be run -- has to run down in the circulation of thought. Most of you obstruct any circula- tion of thought. As far as you go, you will not enter the state of doubt or protest. You will go on playing. We have seen in the -- your -- in your own papers, you have dealt with people who had not -- no time to play and therefore again for- feited their own bliss, because they wanted to be serious too early. All these Ten Commandments in these papers -- in many of your papers, have been mistreated as though they were natural laws. So gentlemen, today I may -- must first make this statement: in the social science, there may be laws, but they are laws against which every one of us can trespass. As you well know, I have heard something about juvenile delinquen- ... [Tape interruption] ... and you don't want to hear this. You want to identify yourself with nature. And you are waiting for the gospel that will prove to you that sex and every- thing -- digestion, the choice of profession -- can be given you by aptitude tests; that is, by nature. That is, it is unexceptional that any man under certain circum- stances will act the same way. Every one of you knows that this isn't true. But you want to believe it, because you would like to disappear within a classifica- tion. -

Candidates Handbook

~a”d~~, Handbook Election 0 Commonwealth of Australia 1996 ISBN 0 644 46520 4 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, Australian Government Publishing Service, GPO BOX 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Published by the Australian Government Publishing Service CONTENTS Abbreviations..................................................................................................................... iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 1 Qualifications....................................................................................................................... 2 Nomination.......................................................................................................................... 4 Thewrit.............................................................................................................................. 10 Ballotpapers..................................................................................................................... 12 Electionfunding andfinancialdisclosure.........................................................................15 Electoraloffences............................................................................................................. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title 1985 Bowling For Soup 2002 Anne-Marie 1 2 3 Len Berry 1 2 3 4 Feist 1 2 3 4 Sumpin New Coolio 17 (Seventeen) Mk 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 2 4 6 8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 2 Become 1 Jewel 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Find U Jewel 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 20th Century Boy T Rex 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 26 Cents Wilkinsons 48 Crash Suzi Quatro 5 4 3 2 1 Manfred Mann 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps 6345 789 Blues Brothers 68 Guns Alarm 7 Ways Abs 74 75 Connells 9 Crimes Damien Rice 99 Red Balloons Nena A and E Goldfrapp A Bad Dream Keane A Better Man Robbie Williams A Better Man Thunder A Big Hunk Of Love Elvis Presley A Boy From Nowhere Tom Jones A Brand New Me Dusty Springfield A Day In The Life Beatles A Deeper Love Aretha Franklin A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers A Different Corner George Michael A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley A Girl Like You Edwin Collins A Girl's Gotta Do Mindy Mccready A Good Heart Fergal Sharkey A Good Hearted Woman Waylon Jennings A Good Tradition Tinita Tikaram A Groovy Kind Of Love Mindbenders A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A House Is Not A Home Brook Benton A Kind Of Magic Queen A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf updated: March 2021 www.djdanblaze.com Can't Find one? Just ask DJ Dan Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Title A Kiss Is A Terrible Thing To Waste Meatloaf A Little Bit