Caucasus — the Mountain of Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Robert Mobili: Thor Heyerdahl and the Udi People

10 Robert Mobili: Thor Heyerdahl and the Udi people This article reviews the interpretation and research of the prominent Nor - wegian traveller and world-renowned scholar, Thor Heyerdahl, and his visit to the village of Nij in Gabala District, a place mainly inhabited by Udi, one of the autochthonous peoples of Azerbaijan. According to Thor Heyerdahl’s theory, Odin, who in Scandinavian mythology was chieftain of the Asi tribe, came from the Caucasus. He also gave a hypothetical inter - pretation of, and scientific credence to, the modern-day Udi being the rem - nants and ancestors of Norwegians. While meeting the Udi, Thor Heyerdahl learnt about their cuisine, ethnography, customs and national traditions. In the attempt to maintain identity and culture against the backdrop of world events some ethnicities have clearly disappeared from the face of the earth, while others, some relatively small in number like the Udi, have struggled for their independence, historical past and integrity and withstood the difficult trials that have befallen them. The surge of interest of Norwegians in Azerbaijan and of Azerbaijanis (including Udi) in Norway began with the work of the great Norwegian traveller, ethnog - rapher, archaeologist and scientist, Thor Heyerdahl. The huge interest of Thor Heyerdahl led him to Azerbaijan at the end of the 20 th century and only then to the lower reaches of the Don in Azov. The differentiation of the ethnogenesis of the Udi people constitutes a lengthy process which took place on the basis of contacts of various cul - tures of east and west. The Udis, whose origins and history have for nearly 200 years been attracting the attention of the academic world, are indigenous peoples of the Caucasus and Azerbaijan (as the historical Motherland). -

Novus Ortus: the Awakening of Laz Language in Turkey”

DOI: 10.7816/idil-04-16-08 idil, 2015, Cilt 4, Sayı 16, Volume 4, Issue 16 NOVUS ORTUS: THE AWAKENING OF LAZ LANGUAGE IN TURKEY Nurdan KAVAKLI 1 ABSTRACT Laz (South Caucasian) language, which is spoken primarily on the southeastern coast of the Black Sea in Turkey, is being threatened by language endangerment. Having no official status, Laz language is considered to be an ethnic minority language in Turkey. All Laz people residing in Turkey are bilingual with the official language in the country, Turkish, and use Laz most frequently in interfamilial conversations. In this article, Laz language is removed from the dusty pages of Turkish history as a response to the threat of language attrition in the world. Accordingly, language endangerment is viewed in terms of a sociolinguistic phenomenon within the boundaries of both language-internal and -external factors. Laz language revitalization acts have also been scrutinized. Having a dekko at the history of modern Turkey will enlighten whether those revitalization acts and/or movements can offer a novus ortus (new birth) for the current situation of Laz language. Keywords: Laz language, endangered languages, minority languages, language revitalization Kavaklı, Nurdan. "Novus Ortus: The Awakening of Laz Language in Turkey”. idil 4.16 (2015): 133-146. Kavaklı, N. (2015). Novus Ortus: The Awakening of Laz Language in Turkey. idil, 4 (16), s.133-146. 1 Arş.Gör., Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Eğitim Fakültesi, İngilizce Öğretmenliği Bölümü, Ankara, nurdankavakli(at)gmail.com 133 www.idildergisi.com Kavaklı, Nurdan. "Novus Ortus: The Awakening of Laz Language in Turkey". idil 4.16 (2015): 133-146. -

Representation of Ethnic Identities in Turkish

French Journal For Media Research – n° 6/2016 – ISSN 2264-4733 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ REPRESENTATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITIES IN TURKISH ADVERTISEMENTS R.Gulay Ozturk Associate Prof of Advertising, İstanbul Commerce University, Advertising Department [email protected] Resumé Dans le monde d’aujourd’hui où tout est formé selon les besoins et les demandes des consommateurs, la détermination de ces derniers et la réalisation d’activités de marketing intégrées offre un avantage compétitif significatif aux marques. S’adresser aux consommateurs selon leurs besoins et demandes, et spécialement dans des pays à diversité culturelle, permet d’atteindre les buts du marketing. De ce point de vue, il est important de prendre en compte les différentes identités culturelles de la population. Chaque groupe ethnique possède sa propre langue, sa croyance, ses valeurs etc. Par contre leur représentation dans l’industrie médiatique peut différer de ce qu’il en est réellement. La Turquie est un pays multiculturel. Divers groupes ethniques y vivent. Par exemple les Kurdes, les Lazes, les Circassiens, les Caucasiens, les Arméniens, les Rums/Grecs, les Alévis, les Yazidis etc. Toutes ces identités ethniques représentent une importante valeur pour la Turquie. Ma recherche porte ainsi sur la représentation des identités ethniques dans les publicités turques. Ma question principale est donc celle-ci: “Comment ces identités sont-elles reflétées dans les pratiques publicitaires”. Les concepts d’identité ethnique, de marketing ethnique et de publicité ethnique y seront tout d’abord expliqués et débattus selon la littérature concernée, puis j’entreprendrais une analyse de contenu sur des exemples de publicité, pour finalement tenter d’expliquer pourquoi l’identité ethnique est importante pour les marques et la publicité en Turquie et dans le monde. -

Programa Saboloo

October 27 14 00 Symposium Opening (The Georgian National Academy of Sciences, 52 Rustaveli Ave., 5th floor, a conference hall) Opening address – President of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences, Acad. T. Gamkrelidze D. Shashkin – Minister of Education and Science of Georgia A. Kvitashvili – Rector of Iv.Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University L. Ezugbaia – Director of Arn. Chikobava Institute of Linguistics G. Gambashidze – President of Fund of Caucasus S. Pasov – Pro-rector of Karachay-Cherkessian State University Kh. Taov – Pro-rector of Kabardo-Balkarian State University A. Abregov – Head of the Chair of the Generel Linguistics of the Adyghe State University Ts. Baramidze – Full Professor at Iv. Javakhishvili State University I. Abdullaev – A senior research-worker of H.Tsadasa Institute of Language, Literature and Art A. Timaev – Head of the Chair of the Chechen language at Chechen State University S. Patiev – Docent of the Chair of the Ingush language at Ingush State Iniversity 15 00 Plenary Report G. Kvaratskhelia (Tbilisi) _ Like-Mindedness and Hereditariness in Science N. Machavariani (Tbilisi) _ Ketevan Lomtatidze's life and activity A. Arabuli, V. Shengelia (Tbilisi) _ Academician Ketevan Lomtatidze's contribution to studying the Abkhaz-Circassian and Kartvelian languages Address Speeches and Memories: M. Lordkipanidze, I. Asatiani, B. Outtier, R. Janashia, N. Andguladze, A. Chincharauli, T. Berozashvili, A. Arabuli, T. Ujukhu... 24 October 28 Sectional Meetings I Section 10 00 _ 11 30 Chairs : I. Abdullaev, G. Kvaratskhelia T. Uturgaidze (Tbilisi) _ On the Subject of the Mix of Models in Lingual Systems A. Khalidov (Grozny) _ About Ascertainment of Affinity of Ibero-Caucasian Languages (in support of M.E. -

Stress Chapter

Word stress in the languages of the Caucasus1 Lena Borise 1. Introduction Languages of the Caucasus exhibit impressive diversity when it comes to word stress. This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the stress systems in North-West Caucasian (henceforth NWC), Nakh-Dagestanian (ND), and Kartvelian languages, as well as the larger Indo-European (IE) languages of the area, Ossetic and (Eastern) Armenian. For most of these languages, stress facts have only been partially described and analyzed, which raises the question about whether the available data can be used in more theoretically-oriented studies; cf. de Lacy (2014). Instrumental studies are not numerous either. Therefore, the current chapter relies mainly on impressionistic observations, and reflects the state of the art in the study of stress in these languages: there are still more questions than answers. The hope is that the present summary of the existing research can serve as a starting point for future investigations. This chapter is structured as follows. Section 2 describes languages that have free stress placement – i.e., languages in which stress placement is not predicted by phonological or morphological factors. Section 3 describes languages with fixed stress. These categories are not mutually exclusive, however. The classification of stress systems is best thought of as a continuum, with fixed stress and free stress languages as the two extremes, and most languages falling in the space between them. Many languages with fixed stress allow for exceptions based on certain phonological and/or morphological factors, so that often no firm line can be drawn between, e.g., languages with fixed stress that contain numerous morphologically conditioned exceptions (cf. -

A Sociological Analysis of Internally Displaced Persons (Idps) As a Social Identity: a Case Study for Georgian Idps

A SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPS) AS A SOCIAL IDENTITY: A CASE STUDY FOR GEORGIAN IDPS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY HAZAR EGE GÜRSOY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AREA STUDIES AUGUST 2021 Approval of the thesis: A SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPS) AS A SOCIAL IDENTITY: A CASE STUDY FOR GEORGIAN IDPS submitted by HAZAR EGE GÜRSOY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Area Studies, the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Dean Graduate School of Social Sciences Assist. Prof. Dr. Derya Göçer Head of Department Department of Area Studies Prof. Dr. Ayşegül AYDINGÜN Supervisor Department of Sociology Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL (Head of the Examining Committee) Middle East Technical University Department of Political Science and Public Administration Prof. Dr. Ayşegül AYDINGÜN (Supervisor) Middle East Technical University Department of Sociology Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT Middle East Technical University Department of International Relations Assist. Prof. Dr. Yuliya BİLETSKA Karabük University Department of International Relations Assist. Prof. Dr. Olgu KARAN Başkent University Department of Sociology iii iv PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. -

Issues in Udi Orthography

JOHN CLIFTON (SIL International and University of North Dakota) GEORGI KEÇAARI (Udi Cultural Association) JONATHAN KIM (SIL International) Issues in Udi Orthography Caucasian languages are renowned for their phonological complexity, including large segmental inventories, long words, morphophonemic alternations, and variation between dialects. The size of the segmental inventories has been particularly problematic, requiring orthographies making extensive use of diacritics or diphthongs. In this paper we examine how the segmental inventories have been represented in various orthographies of the Udi language. In particular, we outline the role of linguistic, sociolinguistic and political factors in a newly proposed orthography currently being used in language development activities. The Udi language is a member of the Lezgi family of North Caucasian languages. Traditionally the Udi people lived in the villages of Oğuz (formerly Vartaşen) and Nic in the Qəbələ District of north-central Azerbaijan. Most speakers of the Vartaşen dialect now live in Georgia. Our research is focused on the Nic variety of Udi. The phonological system of Udi has 15 vowel phonemes and 35 to 38 consonant phonemes depending on the analysis. The Cyrillic orthography used in early Udi primers was based on the technical orthography used by Gukasjan (1974). It contained 15 graphemes for vowels, and 37 graphemes for consonants. Although the Cyrillic orthography was used in the schools, and a fair amount of literature was published using it, few people ever became proficient in using it. We present a number of factors that undoubtedly contributed to this. First, of the 52 total graphemes, 24 were digraphs and 2 were trigraphs. This made long words even longer, and therefore presented problems for developing word attack skills. -

C:\Users\Alice Harris\Documents\Current Docs\Cv

Some data from the project “Synchrony and Diachrony of the Word in Georgian” Alice C. Harris, P.I. (1) ert-i megobar-ta-gan-i one-NOM friend-PL.GEN-from-NOM ‘one of the friends’ (2) ert-i megobr-eb-isa gan one-NOM friend-PL-GEN from ‘one from the friends’ (3) ert-i am saxel-ta-gan-i, saxeldobr op’iza, c’minda č’anur-megruli one-NOM this noun-PL.GEN-from-NOM namely --- pure Laz-Mingrelian porma-a [Šani¥e 1957: 32] form-it.is ‘One of these nouns, namely op’iza, is a pure Laz-Mingrelian form.....’ (4) zogi am pakt’or-ta-gan-i dasaxelebuli-a [Topuria 1979: 263] some this factor-PL.GEN-from-NOM named-it.is ‘Some of these factors are named.’ (i.e. ‘...have names.’) (5) Nominative ert-i megobar-ta-gan-i ‘one of the friends’ Narrative ert-ma megobar-ta-gan-ma Dative ert megobar-ta-gan-s Genitive ert-i megobar-ta-gan-is Instrumental ert-i megobar-ta-gan-it (6) k’ac-i tav-is-i megobar-ta-gan-it ¥lier-i-a man-NOM self-GEN-NOM friend-PL.GEN-from-INST strong-NOM-he.is ‘A mani with [some of] hisi friends is strong.’ (7) ert-i čem-i megobar-ta-gan-isa-tvis es gavak’ete one-GEN my-GEN friend-PL.GEN-from-GEN-for this.NOM I.do.it ‘I did this for one of my friends.’ (9) (a) †megobar-ta gan friend-PL.GEN from ‘from (the) friends’ (archaic) (b) megobar-eb-isa gan friend-PL-GEN from ‘from (the) friends’ (10) mk’a-ta-tve mowing-PL.GEN-month ‘the month of mowing’, i.e. -

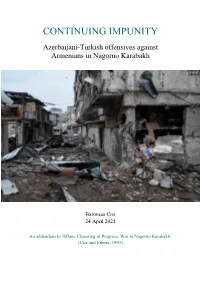

Continuing Impunity

CONTINUING IMPUNITY Azerbaijani-Turkish offensives against Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh Baroness Cox 24 April 2021 An addendum to ‘Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh’ (Cox and Eibner, 1993) CONTENTS Acknowledgements page 1 Introduction page 1 Background page 3 The 44-Day War page 3 Conclusion page 27 Appendix: ‘The Spirit of Armenia’ page 29 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to record my profound sympathy for all who suffered – and continue to suffer – as a result of the recent war and my deep gratitude to all whom I met for sharing their experiences and concerns. These include, during my previous visit in November 2020: the Presidents of Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; the Human Rights Ombudsmen for Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; members of the National Assembly of Armenia; Zori Balayan and his family, including his son Hayk who had recently returned from the frontline with his injured son; Father Hovhannes and all whom I met at Dadivank; and the refugees in Armenia. I pay special tribute to Vardan Tadevosyan, along with his inspirational staff at Stepanakert’s Rehabilitation Centre, who continue to co-ordinate the treatment of some of the most vulnerable members of their community from Yerevan and Stepanakert. Their actions stand as a beacon of hope in the midst of indescribable suffering. I also wish to express my profound gratitude to Artemis Gregorian for her phenomenal support for the work of my small NGO Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust, together with arrangements for many visits. She is rightly recognised as a Heroine of Artsakh as she stayed there throughout all the years of the previous war and has remained since then making an essential contribution to the community. -

Ethno-Cultural Issues and Correction of the Numbers of Ethnic Population in the Republic of Azerbaijan

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan Rezvani, B. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rezvani, B. (2013). Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan. Vossiuspers UvA. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056297336-ethno-territorial- conflict-and-coexistence-in-the-caucasus-central-asia-and-fereydan.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Appendix 3: Ethno-Cultural Issues and Correction of the Numbers of Ethnic Population in the Republic of Azerbaijan Many accounts suggest that the numbers of some ethnic populations in the (Soviet) Republic of Azerbaijan were (and are) underestimated in the official censuses, even in the last Soviet Census of 1989, which is seen as the most accurate Soviet census after the Second World War. -

Preparing Kingdom Leaders for Transformative Ministry

ANNUAL REPORT Preparing Kingdom Leaders for Transformative Ministry 20 18 Sergey Rakhuba, Redeeming the Time, President Preparing for the Future Preach the word; be prepared in “ season and out of season. —2 Timothy 4:2 ” Dear Friend, When the Apostle Paul wrote these words, he was expressing the great vision that God had entrusted to him: to spread the gospel through the Next Generation. He was confident about passing his ministry on to Timothy, his spiritual son. Paul knew that Timothy would face severe challenges—as Paul himself had. So he wrote this letter to encourage Timothy, urging him to “fan into flame the gift of God” and “be strong in the grace that is in Christ Jesus” (2 Timothy 1:6, 2:1). With an eye to the future, Paul also wrote, “The things you have heard me say in the presence of many witnesses entrust to reliable people who will also be qualified to teach others” (2 Timothy 2:2). This biblical concept is very important to us at Mission Eurasia, as we work to train and equip reliable, qualified leaders to bring the gospel to people who desperately need it, despite any challenges they may face. I’m always amazed and gratified to see the passion and commitment of our School Without Walls students and Next Generation leaders for new, strategic outreach ministries. When I see their work in the ministry field, I’m confident that God’s work is in good hands. But right now, the shadow of repression and persecution is descending on many parts of Eurasia. -

Turkey Date: 17 November 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: TUR34020 Country: Turkey Date: 17 November 2008 Keywords: Turkey – Armenians – Orthodox Christians – December 19 organisation – Azadamard publication – Law 302 – Illegal organisations This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Is there any evidence of Armenian Christians being targeted in Turkey in any way? 2. Please provide information regarding the organisation named December 19, including whether it distributes a bulletin called Azadamard. What sort of publication is Azadamard? 3. What is the penalty for a breach of Turkish Law 302, regarding membership of an illegal organisation? RESPONSE Preliminary Note According to a study on Turkish demographics carried out by several Turkish universities the current population of Armenians number 60 million: A report commissioned eight years ago by the highest advisory body in the land investigates how many Turks, Kurds and people of other extractions are living in Turkey. The report comes to light as part