Hansel, Bettina Homestay Program Orientation Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Ball En Ban B

,,. , Vol. 57-No. 2 Philadelphia, March 18, 1911 Price 5 Cents President Johnson, of the American League, in an Open Letter to the Press, Tells of Twentieth Century Advance of the National Game, and the Chief Factors in That Wonderful Progress and Expansion. SPECIAL TO "SPORTING LIFE." race and the same collection of players in an HICAGO, 111., March 13. President exhibition event in attracting base ball en Ban B. Johnson, of the American thusiasts. An instance in 1910 will serve to League, is once more on duty in illustrate the point I make. At the close C the Fisher Building, following the of the American League race last Fall a funeral of his venerable father. While in Cincinnati President John team composed of Cobb, the champion bats son held a conference with Chair man of the year; Walsh, Speaker, White, man Herrmann, of the National Commission, Stahl, and the pick of the Washington Club, relative to action that should be taken to under Manager McAleer©s direction, engaged prevent Kentucky bookmakers from making in a series with the champion Athletics at a slate on American and National League Philadelphia during the week preceding the pennant races. The upshot is stated as fol opening game of the World©s Series. The lows by President Johnson: ©©There is no attendance, while remunerative, was not as need for our acting, for the newspapers vir large as that team of stars would have at tually have killed the plan with their criti tracted had it represented Washington in the cism.- If the promoters of the gambling syn American League. -

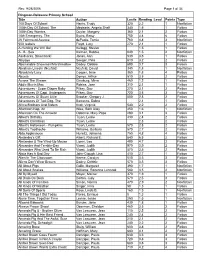

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Dingman-Delaware Primary School Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points Type 100 Days Of School Harris, Trudy 320 2.2 1 Nonfiction 100th Day Of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 340 1.5 1 Fiction 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 360 2.1 2 Fiction 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 750 4.4 6 Fiction 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tomie 760 4.8 3 Nonfiction 500 Isabels Floyd, Lucy 270 2.1 1 Fiction A-Hunting We Will Go! Kellogg, Steven 1.5 1 Fiction A...B...Sea Kalman, Bobbie 640 1.5 2 Nonfiction Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 3.5 1 Fiction Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete 610 3.2 2 Fiction Abominable Snowman/Marshmallow Dadey, Debbie 690 3.7 3 Fiction Abraham Lincoln (Neufeld) Neufeld, David 340 1.8 1 Nonfiction Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 360 1.8 4 Fiction Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 3.5 2 Fiction Across The Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 460 1.2 1 Fiction Addie Meets Max Robins, Joan 310 2.1 1 Fiction Adventures - Super Diaper Baby Pilkey, Dav 270 3.1 2 Fiction Adventures Of Capt. Underpants Pilkey, Dav 720 3.5 3 Fiction Adventures Of Stuart Little Brooker, Gregory J. 500 2.8 2 Fiction Adventures Of Taxi Dog, The Barracca, Debra 2.1 1 Fiction Africa Brothers And Sisters Kroll, Virginia 540 2.2 2 Fiction Afternoon Nap, An Wise, Beth Alley 450 1.6 1 Nonfiction Afternoon On The Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 290 3.1 3 Fiction Albert's Birthday Tryon, Leslie 430 2.4 2 Fiction Albert's Christmas Tryon, Leslie 2.3 2 Fiction Albert's Halloween - Pumpkins Tryon, Leslie 570 2.8 2 Fiction Albert's Toothache Williams, Barbara 570 2.7 2 Fiction Aldo Applesauce Hurwitz, Johanna 750 4.8 4 Fiction Alejandro's Gift Albert, Richard E. -

Leonardo Reviews

LEON4004_pp401-413.ps - 6/21/2007 3:40 PM Leonardo Reviews LEONARDO REVIEWS this book’s ability to convey the world- aid the organizational structure in the Editor-in-Chief: Michael Punt wide connectivity that was emerging in effort to present basic themes. These, Managing Editor: Bryony Dalefield the second half of the 20th century. in turn, allow us more easily to place One of the stronger points of the book the recent art history of Argentina, Associate Editor: Robert Pepperell is the way the research translates the Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela, A full selection of reviews is regional trends of the mid-1940s into Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary published monthly on the LR web site: an environment that was setting the and Poland in relation to that of the <www.leonardoreviews.mit.edu>. stage for the international art world of West. the 1960s to take form. In effect, the The range of artists is equally local communities gave way to a global impressive. Included are (among vision, due, in part, to inexpensive air others) Josef Albers, Bernd and Hilla BOOKS travel, the proliferation of copying Becher, Max Bill, Lucio Fontana, Eva technologies and the growing ease Hesse, On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Bruce of linking with others through long Nauman, Hélio Oiticica, Blinky distance telecommunication devices. Palermo, Bridget Riley, Jesus Rafael BEYOND GEOMETRY: Authored by six writers (Lynn Soto, Frank Stella, Jean Tinguely, and XPERIMENTS IN ORM E F , Zelevansky, Ines Katzenstein, Valerie Victor Vasarely. Among the noteworthy 1940S–1970S Hillings, Miklós Peternák, Peter Frank contributions are the sections integrat- edited by Lynn Zelevansky. -

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections Sixth Grade Sixth Grade: Poetry 3 anyone lived in a pretty how town 3 At Breakfast Time 5 The Ballad of William Sycamore 6 The Bells 8 Beowulf, an excerpt 11 The Blind Men and the Elephant 14 The Builders 15 Casey at the Bat 16 Castor Oil 18 The Charge of the Light Brigade 19 The Children’s Hour 20 Christ and the Little Ones 21 Columbus 22 The Country Mouse and the City Mouse 23 The Cross Was His Own 25 Daniel Boone 26 The Destruction of Sennacherib 27 The Dreams 28 Drop a Pebble in the Water 29 The Dying Father 30 Excelsior 32 Father William (also known as The Old Man's Complaints. And how he gained them.) 33 Hiawatha’s Childhood 34 The House with Nobody in It 36 How Do You Tackle Your Work? 37 The Fish 38 I Hear America Singing 39 If 39 If Jesus Came to Your House 40 In Times Like These 41 The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers 42 Live Christmas Every Day 43 The Lost Purse 44 Ma and the Auto 45 Mending Wall 46 Mother’s Glasses 48 Mother’s Ugly Hands 49 The Naming Of Cats 50 Nathan Hale 51 On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer 53 Partridge Time 54 Peace Hymn of the Republic 55 Problem Child 56 A Psalm of Life 57 The Real Successes 60 Rereading Frost 62 The Sandpiper 63 Sheridan’s Ride 64 The Singer’s Revenge 66 Solitude 67 Song 68 Sonnet XVIII 69 Sonnet XIX 70 Sonnet XXX 71 Sonnet XXXVI 72 Sonnet CXVI 73 Sonnet CXXXVIII 74 The Spider and the Fly 75 Spring (from In Memoriam) 77 The Star-Spangled Banner 79 The Story of Albrecht Dürer 80 Thanksgiving 82 The Touch of the -

National Morgan Horse Show July ?6, 27

he ULY 9 8 MORGAN HORSE NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW JULY ?6, 27 THE MORGAN HORSE Oldest and Most Highly Esteemed of American Horses MORGAN HORSES are owned the nation over and used in every kind of service where good saddle horses are a must. Each year finds many new owners of Morgans — each owner a great booster who won- ders why he didn't get wise to the best all-purpose saddle horse sooner. Keystone, the champion Morgan stallion owned by the Keystone Ranch, Entiat, Washington, was winner of the stock horse class at Wash- ington State Horse Show. Mabel Owen of Merrylegs Farm wanted to breed and raise hunters and jumpers. She planned on thoroughbreds until she discovered the Morgan could do everything the thoroughbred could do and the Morgan is calmer and more manageable. So the Morgan is her choice. The excellent Morgan stallion, Mickey Finn, owned by the Mar-La •antt Farms, Northville, Michigan, is another consistent winner in Western LITTLE FLY classes. A Morgan Horse on Western Range. Spring Hope, the young Morgan mare owned by Caven-Glo Farm Westmont, Illinois, competed and won many western classes throughout the middle-west shows the past couple of years, leaving the popular Quar- ter horse behind in many instances. The several Morgan horses owned by Frances and Wilma Reichow of Lenore, Idaho, usually win the western classes wherever they show. J. C. Jackson & Sons operate Pleasant View Ranch, Harrison, Mon- tana. Their Morgan stallion, Fleetfield, is a many-times champion in western stock horse classes. They raise and sell many fine Morgan horses each year. -

PA THOROUGHBRED REPORT March 2021 / Issue No

PA THOROUGHBRED REPORT March 2021 / Issue No. 84 Madam Meena Madam IN THIS ISSUE PENN VET TEST IS A SPORT BREAKTHROUGH PEACE AND JUSTICE - A SIRE ON THE RISE THE ULTRA-CONSISTENT MADAM MEENA Letter From the Executive Secretary Once again, Governor Wolf has proposed cutting $199 million from the Race Horse Development Trust Fund. Let me begin by saying that this is only a proposal and is very unlikely to gain any traction in the House or the Senate. This same proposal failed to gain any meaningful support last year. This move is illegal and we are confident that the RHDTF will withstand this assault, but we must take every attack on the fund very seriously. I would like to refer you to the following sections of the Trust language: S1405.1 Protection of the Fund – Daily assessments collected or received by the department under section 1405 (relating to the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development Trust Fund) are not funds of the State. S1405.1 – The Commonwealth shall not be rightfully entitled to any money described under this section and sections 1405 and 1406. Our Equine Coalition is made up of Breeder and Horsemen organizations throughout Pennsylvania, both Thoroughbred and Standardbred. We are hard at work with the best lobbying firms in the state to prevent this injustice from happening but we’re going to need your help! If you’re involved in our program and are a resident of PA, please contact your Representative and Senator and tell them your specific story, and if possible, ask others that you may know in our business to share their stories. -

Linda O' Carroll Memorial Adult Amateur Clinic

CALIFORNIA DRESSAGE SOCIETY AUGUST 2017 V. 23, I 8 PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER FRANKE Linda O’ Carroll Memorial Adult Amateur Clinic - North - June 9-11 Having the opportunity to ride with Hilda Gurney Thank you CDS for the 2017 Linda O’Carroll Memorial in the Adult Amateur Clinic series this year was really great! A big CDS Adult Amateur Clinic Series – North with Hilda Gurney. I was thank-you to CDS for sponsoring this educational series for AA’s lucky enough to be chosen from the wait list. and to my East Bay Chapter for selecting me to attend. The first day of the clinic, Hilda worked on basic things with us. I took my Trakehner gelding Tanzartig Ps whom I competed at Keep the reins short, ride with my legs not from my seat, don’t lean I-1 last year. As Hilda did with each horse and rider pair, she honed back. She said I was a very powerful and strong rider, but Ugo didn’t right in with specific instruction to improve our performance. The need that from me. Hilda liked all of my warm-up exercises, and specific exercises she had different pairs use are too numerous to said we had great rhythm and cadence, and our flying changes were outline here, but I particularly liked her comments about warming pretty good. She said that we needed help in learning how to count up our horses as she drew the parallel to the training pyramid and for the threes. Hilda said that I have great feel, and understood what using it as a guide when suppling the horse in warm-up. -

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature As Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature as Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012 List compiled by: Michelle Faught, Aldine ISD, Sheri McDonald, Conroe ISD, Sally Rasch, Aldine ISD, Jessica Scheller, Aldine ISD. April 2012 2 Enhancing the Curriculum with Children’s Literature Children’s literature is valuable in the classroom for numerous instructional purposes across grade levels and subject areas. The purpose of this bibliography is to assist educators in selecting books for students or teachers that meet a variety of curriculum needs. In creating this handout, book titles have been listed under a skill category most representative of the picture book’s story line and the author’s strengths. Many times books will meet the requirements of additional objectives of subject areas. Summaries have been included to describe the stories, and often were taken directly from the CIP information. Please note that you may find some of these titles out of print or difficult to locate. The handout is a guide that will hopefully help all libraries/schools with current and/or dated collections. To assist in your lesson planning, a subjective rating system was given for each book: “A” for all ages, “Y for younger students, and “O” for older students. Choose books from the list that you will feel comfortable reading to your students. Remember that not every story time needs to be a teachable moment, so you may choose to use some of the books listed for pure enjoyment. The benefits of using children’s picture books in the instructional setting are endless. The interesting formats of children’s picture books can be an excellent source of information, help students to understand vocabulary words in different contest areas, motivate students to learn, and provide models for research and writing. -

Results Book

Results Book Equestrian 6 - 19 August Version History 1.0 19/08/2016 Veronica Costa First version Report Update: Eventing - 1.1 13/09/2016 Veronica Costa Competition Officials Equestrian Hipismo / Sports equéstres Eventing CCE (Concurso completo de equitação) / CC (Concours complet) Competition Format and Rules Formato e regras da competição / Format et régles de compétition As of 25 JUL 2016 Olympic competition format Eventing at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games comprises the team and individual events, and is made up of the following distinct tests: dressage, cross-country and jumping. There will also be two official horse inspections to test the health and wellbeing of the animals. Each test takes place on consecutive days, during which each athlete rides the same horse. The results count towards the individual and team events. A team consists of three to four horse/rider combinations. The total points are calculated by combining the overall scores of the team’s best three athletes. After the three tests, the eventing team medals are awarded. The eventing individual competition adds a fourth round, as its jumping test has a qualifier preceding the final. After the first jumping test, the 25 highest ranked athletes (including all riders tied for 25th place, with a maximum of three participants per NOC) qualify for the jumping individual final. The final ranking of the individual athletes is determined by the combined points earned in all four tests (dressage, cross country, first jumping test, jumping individual final). The tests: Dressage This test of compulsory movements evaluates the horse's obedience, flexibility and harmony with the rider. -

Eva's Death Is a Mystery the Death of Eva Blau, 17 Year Old Hut Appeared

- • W"I - THE BANK OF AMERICA ml rYou don't have to strain by any means to were arranging contracts to put their land in maintain five branches in South Vietnam. Manhattan Bank and our friend the Bank of vilify the Bank of America. Just a simple agricultural preserve the Bank of America Recently a banker was quoted as saying, America. account of it's policies and actions are btought suit against the farm ow11e;s whos~ "\\" e believe we're going to win this war These investors in conjunction with the enough to tell of the bank's predatory nature. land they held mortgages on to prevent and afterwards you '11 have a major job of Asian Development Bank underwrite the While Western Demokracies were acqui completion of the contract with the county reconstruction on your hands. That wiJl securities necessary for development of escing to the fascist dictators, the double government. The Bank certainly did not want mean financing and financing means banks." the Third World countries, This effectively diplomacy was at the same time mouthing the land they had underwritten to be put in That's why the Bank of America refused to puts the Third Wor Id under the directorship condemnations of fascism and the Bank of agricultural preserve when it could possibly oppose the war for they hope to stay and of American business which includes the Italy in true patriotic spirit became the be subdivided and built upon. The notion of make money after the war is \Von. Bank of America as the nation's largest Bank of America. -

Download the Report

inaugural report Oregon Cultural Trust fy 2003 – fy 2006 Grant dollars from the Cultural Trust are transformational. In historic Oregon City, they helped bring a more stable operating structure to separate organizations with marginal resources. As a result, we continue to share Oregon’s earliest stories with tens of thousands of visitors, many of them students, every year. —David Porter Clackamas Heritage Partners September 2007 Dear Oregon Cultural Trust supporters and interested Oregonians: With genuine pride we present the Oregon Cultural Trust’s inaugural report from the launch of the Trust in December 2002 through June 30, 2006 (the end of fiscal year 2006). It features the people, the process, the challenges and the success stories. While those years were difficult financial ones for the State, the Trust forged ahead in an inventive and creative manner. Our accomplishments were made possible by a small, agile and highly committed staff; a dedicated, hands-on board of directors; many enthusiastic partners throughout the state; and widespread public buy-in. As this inaugural report shows, the measurable results, given the financial environ- ment, are almost astonishing. In brief, more than $10 million was raised; this came primarily from 10,500 donors who took advantage of Oregon’s unique and generous cultural tax credit. It also came from those who purchased the cultural license plate, those who made gifts beyond the tax credit provision, and from foundations and in-kind corporate gifts. Through June 30, 2006, 262 grants to statewide partners, county coalitions and cultural organizations in all parts of Oregon totaled $2,418,343. -

Issue Two 2020

Issue Two T H E 2020 QUARTERLY Official Publication of the United States Icelandic Horse Congress Member Association of FEIF (InternationalISSUE Federation TWO of2020 Icelandic • ICELANDIC Horse Associations) HORSE QUARTERLY 1 2 ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY • ISSUE TWO 2020 ISSUE TWO 2020 • ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY 3 4 ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY • ISSUE TWO 2020 ISSUE TWO 2020 • ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY 5 Boarding Training d o n d Lessons Education a a l r e o c l Sales Trips I o d C n i Barn address 719-209 2312 n 13311 Spring Valley Rd [email protected] Larkspur, CO 80118 www.tamangur-icelandics.com F I 6 ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY • ISSUE TWO 2020 ISSUE TWO 2020 • ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY 7 ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY THE ICELANDIC HORSE QUARTERLY 10 NEWS Issue Two 2020 10 USIHC News Official Publication of the United States Icelandic Horse Congress (USIHC), 14 FEIF News a member association of FEIF 17 Club Updates (International Federation of Icelandic Horse Associations). ©2020 All rights reserved. 22 FEATURES The Icelandic Horse Quarterly is published in March, June, September, and December 22 Going Virtual by Alex Pregitzer & Emily Potts by the USIHC as a benefit of membership. Renew online at www.icelandics.org. 25 Made in Germany by Lisa Cannon Blumhagen Deadlines are January 1 (for the March 29 Devotion by Tory Bilski issue), April 1, July 1, and October 1. We reserve the right to edit submissions. All 30 Iceland’s First Horse Imports by Kristina Stelter articles represent the opinions of their authors alone; publication in the Quarterly does 32 The Road to Collection by Sigrún Brynjarsdóttir not imply an endorsement of any kind by the USIHC.