Light-Footed Clapper Rail Management, Study, and Propagation in California, 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION UC-Stallcup TEXT.indd 1 1/23/14 11:30 AM This contribution to the California Natural History Guide Series of the University of California Press follows a long tradi- tion of books that explain, explore, and celebrate the natural riches of California and beyond. Our intent is to tell beginning birders, or curious naturalists, the how, what, when, where, and why of birding. Because birds are so mobile, some individuals of most spe- cies can wander far from their natal homes and appear any- where. Here we have tried to include only those species most likely to be seen along the coast, from Big Sur to the Oregon border. This is not a field guide to bird identification, but a field guide to the birds themselves. Birding is a word that encompasses many concepts. For some, the activity of searching for and observing birds is a clear window into the natural world, an affirmation of its beauty and its peacefulness. To others, birding is a delightful diversion from the hectic or perhaps boring daily routine of the mod- ern world— providing calm amid the chaos. Birds are nature’s ambassadors, connecting us through their ancient lineage to evolution’s astonishing creativity and offering us some guid- ance, through our study of their habitat needs, in our steward- ship of the Earth. Some people have found the wonders of birds to be the perfect antidote to sadness or loneliness, or a path to comradeship with kindred spirits; others consider the complex- ities of identification or behavior an intellectual challenge. -

Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community Northeast Gulf Science Volume 2 Article 2 Number 1 Number 1 6-1978 Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C. Holliman Birmingham-Southern College DOI: 10.18785/negs.0201.02 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Holliman, D. C. 1978. Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama. Northeast Gulf Science 2 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol2/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holliman: Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 2, No.1, p. 24-34 June 1978 CLAPPER RAIL (Rallus longirostris) STUDIES IN ALABAMAl Dan C. Holliman Biology Department Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham, AL 35204 ABSTRACT: The habitat and distribution of the clapper rail Rallus longirostris saturatus in salt and brackish-mixed marshes of Alabama is described. A total of 4,490 hectares of habitat is mapped. Smaller units of vti'getation are characterized in selected study areas. A comparison of these plant communities and call, count data is shown for each locality. Concentrations of clapper rails generally occurrecj in those habitats with the higher percentage of Spartina alterniflora. A census techni que utilizing taped calls is described. Trapping procedures are given for drift fences and funnel traps. -

Light-Footed Ridgway's (Clapper) Rail in California

Light-footed Ridgway’s (Clapper) Rail in California 2018 Season By Richard Zembal, Susan M. Hoffman, John Konecny, and Beth Sabiston Final Report to US Fish and Wildlife Service and California Department of Fish and Wildlife Light-footed Ridgway’s (Clapper) Rail in California 2018 Season Richard Zembal, Susan M. Hoffman, John Konecny, and Beth Sabiston Clapper Rail Recovery Fund Huntington Beach Wetlands Conservancy 24821 Buckboard Lane Laguna Hills, CA 92653 December 21, 2018 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 2 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Population Monitoring .........................................................................................................4 Nest Monitoring ...................................................................................................................5 Breeding in Zoological Facilities .........................................................................................6 Banding and Tracking ..........................................................................................................8 STUDY AREAS ............................................................................................................................ -

Light-Footed Clapper Rail Management and Population Assessment, 1993

State of California The Resource Agency Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Management Division LIGHT-FOOTED CLAPPER RAIL MANAGEMENT AND POPULATION ASSESSMENT, 1993 by Richard Zembal Nongame Bird and Mammal Program Report, 94-6 FINAL REPORT TO California Department of Fish and Game 1416 Ninth Street Sacramento, CA 95814 CONTRACT FG2327 (FY 92/93) Partially Supported by Section 6 Federal Grant-in-Aid Funding for Endangered Species, California, EW92, X-l LIGHT-FOOTED CLAPPER RAIL MANAGEMENT AND POPULATION ASSESSMENT, 1993 CONTRACTOR California State University, Long Beach Foundation Long Beach, California 90840 PROJECT ADMINISTRATOR Dr. Charles T. Collins Department of Biology California State University Long Beach, CA 90840 AUTHOR AND PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR Richard Zembal Research Associate State of California The Resources Agency Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Management Division LIGHT-FOOTED CLAPPER RAIL CENSUS AND STUDY, 1993 by Richard Zembal Research Associate, Biology Department California State University Long Beach, CA 90840 ABSTRACT The fourteenth consecutive annual census of the endangered light-footed clapper rail (Rallus longirostris levipes) was conducted by call counts throughout the bird's range in California, 3 March - 15 April 1993. There were 300 pairs of clapper rails exhibiting breeding behavior in 13 marshes, a 9% increase over 1992. One hundred and forty-two pairs, or 47.3% of the state total, were detected at Upper Newport Bay. The subpopulations in the Tijuana Marsh National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), Seal Beach NWR, and Upper Newport Bay totalled 270 pairs, or 90% of the California population. Most of the subpopulations are small and face serious problems that should be dealt with through increased management and the provision of additional habitat or they will be lost. -

ON 23(3) 461-466.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 23: 461–466, 2012 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society FIRST DESCRIPTION OF THE NEST AND EGGS OF THE PLAIN-FLANKED RAIL (RALLUS WETMOREI) Adriana Rodríguez-Ferraro1,2, Eugenia Sánchez2, & Miguel Lentino3 1Departamento de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Apdo. 89.000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela. E-mail: [email protected] 2Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular de Vertebrados, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Apdo. 89.000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela. 3Fundación William H. Phelps, Apdo. 2009, Caracas 1010-A, Venezuela. Primera descripción del nido y los huevos de la Polla de Wetmore (Rallus wetmorei). Key words: Plain-flanked Rail, Rallus wetmorei, eggs, mangrove, nest, Venezuela. INTRODUCTION conservation priorities in Venezuela (Rodrí- guez et al. 2004). Main threats for this rail The Plain-flanked Rail (Rallus wetmorei) is a are the loss and deterioration of mangrove Venezuelan endemic species deserving urgent habitat as a consequence of expanding attention from a conservation perspective. touristic developments and activities derived This bird was first described in the mid-1940s from petrochemical industries (Rodríguez & (Zimmer & Phelps 1944), and after a few Rojas-Suárez 2008). These problems even other observations during the following 10 exist within the boundaries of the few pro- years, it went unrecorded for almost three tected areas (three national parks and one decades, until rediscovered in 1999 (Hilty wildlife refuge) where the species is known to 2003). It is restricted to a small area along the occur. central coast of Venezuela where it is known Recovery efforts of endangered birds from eight localities (Taylor 1996), but in have been hampered by the lack of basic recent years, it has been found in only five of knowledge on their biology, thus, research these sites (Rodríguez-Ferraro & Lentino in focused on determining biological character- prep.). -

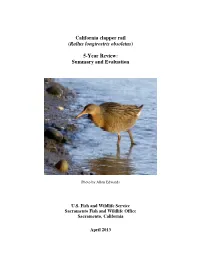

California Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris Obsoletus) 5-Year Review

California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus ) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photo by Allen Edwards U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office Sacramento, California April 2013 5-YEAR REVIEW California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. The California clapper rail was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act in 1970, so was not subject to the current listing processes and, therefore, did not include an analysis of threats to the California clapper rail. In this 5-year review, we will consider listing of this species as endangered or threatened based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of this species. We will consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

May2014 Newsletter.Pub

May 2014 Some things beautiful and some things rare in Oklahoma birds and wildlife Jim and Tony Solorio will be the presenters at the May 19 meeting of the Oklahoma City Audubon Society. They will talk about their adventures in good old Oklahoma. Jim has been lucky enough to have a job that gets he and his son Tony out all over the state. He works as the state of Oklahoma manager for a company that takes care of restaurants and nursing homes. They did their share of hunting and fishing over the years but, about 10 years ago, they got a couple of disposable cameras for Christmas and went to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge where they took a lot of disposable camera pictures. They then moved up to a DSLR camera. They had just watched an Outdoor America show where Marty Stouffer said that what modern hunters capture is not a dead body, but rather the living form of an animal, as a lasting mental image, a lifeless checkmark, or a photographic negative. This non- Photo © Tony Solorio consumptive use of wildlife is the fastest growing. Birders and photographers now out number hunters 2 to 1. Tony grew up just loving the outdoors. He does all the photography on their trips — he has the eye of an eagle! He spots the wildlife, when Jim can’t find it he points it out. Jim does most of the driving because at 9 months old Tony had spinal meningitis and he barely survived. He has had seizures ever since. Tony has attended OKCCC for three years and has been through two years of computer school. -

2020-2021 NEBRASKA BIRD LIST See Science Olympiad General Rules, Eye Protection & Other Policies on As They Apply to Every Event

2020-2021 NEBRASKA BIRD LIST See Science Olympiad General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event Kingdom – ANIMALIA ORDER: Pelecaniformes ORDER: Gruiformes Pelicans (Pelecanidae) Rails, Gallinules, and Coots (Rallidae) Phylum – CHORDATA American White Pelican Pelecanus Clapper Rail Rallus longirostris Subphylum – VERTEBRATA erythrorhynchos Sora Bitterns, Herons, and Allies Purple Gallinule Class - AVES (Ardeidae) American Coot Family Group (Family Name) American Bittern Cranes (Gruidae) Common Name Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Sandhill Crane Antigone canadensis [Scientific name is in italics] Snowy Egret Egretta thula Whooping Crane Grus americana Green Heron ORDER: Anseriformes Black-crowned Night-heron ORDER: Charadriiformes Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Ibises and Spoonbills Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Black-bellied Whistling-duck (Threskiornithidae) American Golden-Plover Snow Goose Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Canada Goose Branta canadensis Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Trumpeter Swan ORDER: Suliformes Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) American Oystercatcher Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Double-crested Cormorant Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) Northern Shoveler Phalacrocorax auritus Black-necked Stilt Green-winged Teal Darters (Anhingida) American Avocet Recurvirostra Canvasback Anhinga Anhinga anhinga americana Hooded Merganser Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Sandpipers, Phalaropes, -

Notes on the Food of the California Clapper Rail

270 Vol. 43 NOTES ON THE FOOD OF THE CALIFORNIA CLAPPER RAIL By JAMES MOFFITT Comparatively little has been published upon the food habits of the California Clapper Rail (Rallus obsoletus obsoletus). Grinnell, Bryant and Storer (Game Birds of California, 1918:288) devoted but one short paragraph to a summation of the infor- mation then available. Laidlaw Williams (Condor, 31, 1929:52-56) contributed an important paper on the subject. Because this is a “threatened species” which has been greatly reduced in numbers for various reasons in the past 50 years, knowledge of its natural history is especially desirable. The “spotty” distribution of this rail, its abundance in some localities and absence from others seemingly as suitable, suggests that ecological differences funda- mental to rails exist in marshes of similar external appearance. For instance, clapper rails are extremely abundant in the unreclaimed parts of south San Francisco Bay, where tide-flooded salicornia marsh provides the preferred habitat. Yet similar marshes in the northern part of the Bay and at the south end of Tomales Bay, Marin County, support but a small population of rails. The speciesis apparently unknown from Suisun Bay and the entire delta area above Carquinez Strait, where extensive salicornia marshes also exist. This region is one of reduced salinity, with quite fresh water seasonally in the spring, which may possibly affect rail distribution through influence upon food supply. This statement is necessarily pure surmise because of our meager knowledge of the ecology of the marshes and of the clapper rail. There is indeed need for a com- prehensive study of the natural history of the species along the lines suggested by the writer (The Gull, 22, 1940: 4546). -

Marsh Bird Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2010-2015 Marsh Birds Guild American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps American Coot Fulica americana Purple Gallinule Porphyrula martinica Black Rail Laterallus jamaicensis Sedge Wren Cistothorus platensis Clapper Rail Rallus longirostris Sora Porzana carolina Common Gallinule Gallinula galeata Yellow Rail Coturnicops noveboracensis King Rail Rallus elegans Virginia Rail Rallus limicola Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago delicata NOTE: The Black Rail is described in more detail in a separate species account. The Wilson’s Snipe is also referenced in the Migratory Shorebirds Guild. Contributor (2005): John E. Cely Reviewed and Edited (2012): Craig Watson (USFWS); (2013) Lisa Smith and Christy Hand (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions The members of the Marsh Birds Guild vary widely in appearance and size. The rails and bitterns have long, slender beaks and stilt-like legs for wading while the coot and grebe have shorter legs with webbed feet for paddling. Sizes for the species vary from the large American Bittern at 58 cm (23 in.) to the small Sedge Wren at 11 cm (4.5 in.). The most colorful of the group is the Purple Gallinule. The male has plumage in shades of green, purple, and blue with bright American Bittern photo by BLM yellow feet and long toes (Sauer et al. 2000). The Black Rail is the smallest North American rail measuring 10-15 cm (4 -6 in.) in length and 35 g (1.2 oz.) in weight (Eddleman et al. 1994). Adult rails have strikingly red irises, a dark gray to blackish head, gray neck and breast, rufous nape, and a black and white patterned back.