Former NBA Player Brian Grant Combats Parkinson's with Exercise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Total Person Graduating Every Men’S Basketball Senior Since 1986

THE TOTAL PERSON GRADUATING EVERY MEN’S BASKETBALL SENIOR SINCE 1986 Xavier University has earned a reputation for student-athlete academic success. Every senior student-athlete in the men’s basketball program, including Matt Stainbrook (seen here at his graduation with Xavier University President Michael J. Graham, S.J.), has graduated for the last 30 school years. That streak began in the 1985-86 school year. Xavier makes a promise to each student it recruits. That’s a promise XU keeps and celebrates every May at graduation. 4 PLAYERS WHO COMPLETED THEIR % THAT XAVIER’S GRADUATION STREAK ELIGIBILITY GRADUATED 1986 6 100% 1987 NO SENIORS 1988 4 100% 1989 2 100% 1990 4 100% 1991 3 100% 1992 NO SENIORS 1993 6 100% 1994 4 100% 1995 5 100% 1996 1 100% 1997 4 100% 1998 4 100% 1999 4 100% 2000 1 100% 2001 3 100% 2002 3 100% 2003 3 100% 2004 3 100% 2005 1 100% 2006 5 100% 2007 4 100% 2008 3 100% 2009 3 100% 2010 1 100% 2011 6 100% 2012 5 100% 2013 3 100% 2014 3 100% 2015 2 100% SINCE 1986 96 100% SISTER ROSE ANN FLEMING XAVIER ATHLETIC HALL OF FAMER Since she became Xavier’s academic advisor in 1985, Sr. Rose Ann Fleming (seen here with 2010 graduate Jason Love) has helped every men’s basketball player who has reached his final year of athletic eligibility to graduate. A book has been written about her, “Out of Habit.” Last season her “retired jersey” banner was hung at Cintas Center. -

GAME DAY Saturday, March 1, 2014 • 4:15 P.M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Men's Basketball Programs Men's Basketball 3-1-2014 Cedarville vs. Salem International Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/mens_basketball_programs Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cedarville University, "Cedarville vs. Salem International" (2014). Men's Basketball Programs. 47. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/mens_basketball_programs/47 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Men's Basketball Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GAME DAY Saturday, March 1, 2014 • 4:15 p.m. Congratulations, Cedarville University Senior Brian Grant! vs. Salem International University Inside this issue.... • Today!s Game Preview 2 • Yellow Jacket Weekly Blog 2 • Stat Comparisons 3 • Probable Starting Lineups 3 • Last Time Out 5 • Looking Ahead 5 • Follow the Yellow Jackets 5 • 2013-14 CU Schedule / Results 7 • All-Time Series Records 8 • 500 Rebound / 1,000 Point Club 9 • 2013-14 Cedarville / Salem Stats 10 • Jacket / Tiger Rosters 11 • Meet Head Coach Pat Estepp 12 • G-MAC Men!s Basketball 12-13 • CU Season Top 10 Leaders 15 • CU Career Top 10 Leaders 15 • Yellow Jacket Profile 16 • NCAA II Rankings 17 • 2013-14 Cheerleaders 20 12 three-pointers combined by the Lady Jackets & Yellow Jackets today & everyone!s ticket is good for a FREE TACO at Taco Bell in Xenia or Springfield! yellowjackets.cedarville.edu Today’s Game Preview Lane Vander Hulst’s Blog The Cedarville University Yellow Jackets host the Salem February 25, 2014 International University Tigers in Great Midwest Athletic Conference action today in the Callan Athletic Center. -

2019-20 Horizon League Men's Basketball

2019-20 Horizon League Men’s Basketball Horizon League Players of the Week Final Standings November 11 .....................................Daniel Oladapo, Oakland November 18 .................................................Marcus Burk, IUPUI Horizon League Overall November 25 .................Dantez Walton, Northern Kentucky Team W L Pct. PPG OPP W L Pct. PPG OPP December 2 ....................Dantez Walton, Northern Kentucky Wright State$ 15 3 .833 81.9 71.8 25 7 .781 80.6 70.8 December 9 ....................Dantez Walton, Northern Kentucky Northern Kentucky* 13 5 .722 70.7 65.3 23 9 .719 72.4 65.3 December 16 ......................Tyler Sharpe, Northern Kentucky Green Bay 11 7 .611 81.8 80.3 17 16 .515 81.6 80.1 December 23 ............................JayQuan McCloud, Green Bay December 31 ..................................Loudon Love, Wright State UIC 10 8 .556 70.0 67.4 18 17 .514 68.9 68.8 January 6 ...................................Torrey Patton, Cleveland State Youngstown State 10 8 .556 75.3 74.9 18 15 .545 72.8 71.2 January 13 ........................................... Te’Jon Lucas, Milwaukee Oakland 8 10 .444 71.3 73.4 14 19 .424 67.9 69.7 January 20 ...........................Tyler Sharpe, Northern Kentucky Cleveland State 7 11 .389 66.9 70.4 11 21 .344 64.2 71.8 January 27 ......................................................Marcus Burk, IUPUI Milwaukee 7 11 .389 71.5 73.9 12 19 .387 71.5 72.7 February 3 ......................................... Rashad Williams, Oakland February 10 ........................................ -

Fashion Week Miami Beach

FUNKSHION: Fashion Week Miami Beach is a fi ve day event that provides an intelligent, innovative platform for progressive, established, and emerging designers to showcase their collections to media, celebrities, international buyers, and select style makers. The shows are geared towards designer diffusion collections and innovative lifestyle brands. Designers will integrate music into their shows, many personally selecting their favorite celebrity DJs or bands to preside over their runway spectacles. funkshion noun fusion of music and fashion worlds Real Time Funkshion ART Celebrating 15 seasons of Funkshion: Fashion Week Miami Beach, two artists created 15 art installations / sculptures inspired by fashion, music and Miami Beach. For 15 days in the tradition of the Real-Time- Art concepts Djordje IsHere and Vladimir composed one sculpture a day using recycled and found objects from the Funkshion warehouse. They even set up a temporary photo studio at the premises to shoot pictures of the art sculptures using Funkshion runway lights for fashion shows. The 15 works of art produced represent their creative answers to the connection of the art and fashion worlds – the outcome is extraordinary pieces created with limited resources and in limited time. Funkshion takes over Ocean Driveve withwith two custom built venues on the beach: Maxim Magazine Parkk on NinthN presented by FILA and the main tent where designers suchuch as Nicole Miller, Miss Sixty, Fred Perry, Marithe and Francois Girbaudaud andan others showcased their new collections. Among attendees werere P. Diddy,D Alonzo Mourning, Brian Grant, Patricia Fields and others. FunkshionFunk benefi ted Brian Grant and Alonzo Mourning Charities. -

Brian Grant's Battle with Parkinson Disease

Brian Grant's Battle with Parkinson Disease Friends quick to enlist in Brian Grant's battle against Parkinson's disease By Mike Tokito, The Oregonian, 7/29, 10:49 p.m. PT Lauren Forman remembers the day she and Brian Grant were sitting in Cafe DuBerry, discussing plans for an event to raise money to battle Parkinson's disease. Grant wanted one of his former NBA coaches, Pat Riley, to be the event's keynote speaker. So they called Riley. "Within seconds he's like, 'Brian, whatever you need, I'm there -- send me the info,'" said Forman, executive director of the Brian Grant Foundation. That sort of personal response to Grant, the highly-respected former Trail Blazers forward who is one of an estimated 1 million people in the United States with Parkinson's, explains the impressive guest list for "Shake It Till We Make It." The two-day event starts Sunday with a dinner, meet-and-greet and auction at the Rose Garden, and concludes Monday with a golf event at Pumpkin Ridge. The two celebrities most linked to Parkinson's will be there -- boxing great Muhammad Ali, and actor Michael J. Fox, whose foundation will be the beneficiary. Also slated to appear are Bill Russell, Bill Walton, Brandon Roy, Charles Barkley, Clyde Drexler, Greg Oden, Steve Nash, Terry Porter and Rasheed Wallace. 1 / 3 Brian Grant's Battle with Parkinson Disease "These guys are all flying in on their own dime," Forman said. "They're coming in because they care about him." Grant, 38, played 12 seasons in the NBA before retiring in 2006. -

2003 - 2004 Roster

As of 11/19 2003 - 2004 ROSTER Team: JKnights 1 Team: Rainbows 2 Team: Madman 3 Owner: Isaac Owner: Carl Owner: Nathan NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM Kevin Garnett F Timberwolves Tim Duncan C Spurs Shaquille O'Neal C Lakers Ray Allen G Supersonics Shawn Marion F Suns Allen Iverson G 76ers Jermaine O'Neal C Pacers Steve Francis G Rockets Amare Stoudemire F Suns Vince Carter G Raptors Jason Terry G Hawks Steve Nash G Mavericks Gilbert Arenas G Wizards Ricky Davis F Cavaliers Jerry Stackhouse G Wizards Andrei Kirilenko F Jazz Donyell Marshall F Bulls Lamar Odom F Heat Predrag Stojakovic F Kings Jason Williams G Grizzlies Kurt Thomas C Knicks Jamal Crawford G Bulls Juwan Howard F Magic Michael Redd G Bucks Theo Ratliff C Hawks Eric Snow G 76ers Shane Battier F Grizzlies Ron Artest F Pacers Jamaal Magloire C Hornets Matt Harpring F Jazz Team: Wasabi Belly 4 Team: Blank 5 Team: Loose Screw 6 Owner: Randall Owner: Chris Owner: Keith NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM Dirk Nowitzki C Mavericks Tracy McGrady G Magic Paul Pierce G Celtics Elton Brand F Clippers Ben Wallace C Pistons Baron Davis G Hornets Gary Payton G Lakers Stephon Marbury G Suns Yao Ming C Rockets Shareef Abdur Rahim F Hawks Pau Gasol F Grizzlies Chris Webber F Kings Sam Cassell G Timberwolves Jamal Mashburn F Hornets Drew Gooden F Magic Zydrunas Ilgauskas C Cavaliers Rasheed Wallace F Trailblazers Caron Butler F Heat Brian Grant F Heat Jalen Rose G Bulls Michael Finley G Mavericks Jamaal Tinsley G Pacers Chauncey Billups G Pistons Rashard Lewis F Supersonics Troy Murphy F Warriors Alonzo Mourning C Nets Antonio Davis C Raptors Jason Richardson G Warriors Glenn Robinson F 76ers Anthony Carter G Spurs Team: Ctity Worker 7 Owner: Eric NAME POS TEAM Kobe Bryant F Lakers Jason Kidd G Nets LeBron James G Cavaliers Carmelo Anthony F Nuggets Michael Olowokandi C Timberwolves Karl Malone F Lakers Andre Miller G Nuggets Antoine Walker F Mavericks Kenyon Martin F Nets Brad Miller C Kings. -

Blue Devils Stalk Jayhawks for NCAA Title, 72-65

NCAA VICTORY EDITION At last Once college basketball's perennial brides maids, the Duke Blue Devils win it all in their THE CHRONICLE ninth trip to the Final Four. TUESDAY, APRIL 2, 1991 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 3,000 VOL. 86, NO. 125A DUKE TAKES CROWN! Blue Devils stalk Jayhawks for NCAA title, 72-65 By MARK JAFFE INDIANAPOLIS — For the first time in its history, the men's basketball team captured an NCAA Championship. The Blue Devils used a 17-7 run early in the second half to pull away from Kansas and fought off a furious late-game assault by the Jayhawks to win, 72-65, Monday night at the Hoosier Dome. "I'm so happy for our guys," said head coach Mike Krzyzewski. "I'm not sure if anyone's ever played harder for 80 minutes to win a national title." The Blue Devils (32-7) had fallen short ofthe championship in eight previous trips to the Final Four, including four ofthe last five years. But in 1991 Duke would not be denied. "I feel good but [not winning the title] has never been a monkey on my back," Krzyzewski said. "Did you see the players' faces? I looked at my three daughters and saw them crying. I'm just so happy." Christian Laettner, the most outstand ing player ofthe tournament, had his first double-double—18 points and 10 rebounds — in 12 games to lead Duke. "I'm just very happy about [most out standing player honors]," Laettner said. "But there are more things I'm more happy about — a national championship, a big trophy for coach to bring back to Duke. -

Reevaluating Amateurism Standards in Men's College Basketball

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 35 2002 Reevaluating Amateurism Standards in Men's College Basketball Marc Edelman University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Marc Edelman, Reevaluating Amateurism Standards in Men's College Basketball, 35 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 861 (2002). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol35/iss4/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REEVALUATING AMATEURISM STANDARDS IN MEN'S COLLEGE BASKETBALL Marc Edelman* This Note argues that courts should interpretNCAA conduct under the Principle of Amateurism as a violation of§ 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act and that courts should order NCAA deregulation of student-athletes' indirectfinancial activities. Part I of this Note discusses the history of NCAA regulation, specifically its Prin- ciple of Amateurism. Part II discusses the current impact of antitrust laws on the NCAA. Part III argues that the NCAA violates antitrust laws because the Princi- ple of Amateurism's overall effect is anticompetitive. Part IV argues the NCAA could institute an amateurism standard with a net pro-competitive effect by allow- ing student-athletes to pursue business opportunities neutral to college budgets; potential revenue sources would include: summer professional leagues, endorse- ment contracts, and paid-promotionalappearances. -

Memphis Grizzlies 2016 Nba Draft

MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 2016 NBA DRAFT June 23, 2016 • FedExForum • Memphis, TN Table of Contents 2016 NBA Draft Order ...................................................................................................... 2 2016 Grizzlies Draft Notes ...................................................................................................... 3 Grizzlies Draft History ...................................................................................................... 4 Grizzlies Future Draft Picks / Early Entry Candidate History ...................................................................................................... 5 History of No. 17 Overall Pick / No. 57 Overall Pick ...................................................................................................... 6 2015‐16 Grizzlies Alphabetical and Numerical Roster ...................................................................................................... 7 How The Grizzlies Were Built ...................................................................................................... 8 2015‐16 Grizzlies Transactions ...................................................................................................... 9 2016 NBA Draft Prospect Pronunciation Guide ...................................................................................................... 10 All Time No. 1 Overall NBA Draft Picks ...................................................................................................... 11 No. 1 Draft Picks That Have Won NBA -

When Is a Basket Not a Basket? the Basket Either Was Made Before the Clock Expired Or Nswer: When 3 the Protest by After

“Local name, national Perspective” $3.95 © Volume 4 Issue 6 NBA PLAYOFFS SPECIAL April 1998 BASKETBALL FOR THOUGHT by Kris Gardner, e-mail: [email protected] A clock was involved; not a foul or a violation of the rules. When is a Basket not a Basket? The basket either was made before the clock expired or nswer: when 3 The protest by after. The clock provides tan- officials and deter- the losing gible proof. This wasn’t a commissioner mina- team. "The charge or block call. Period. David Stern tion as Board of No gray area here. say so. to Governors Secondly, it’s time the Sunday, April 12, the whethe has not league allows officials to use Knicks apparently defeated r a ball seen fit to replay when dealing with is- the Miami Heat 83 - 82, on a is shot adopt such sues involving the clock. It’s last second rebound by G prior a rule," the sad that the entire viewing Allan Houston. Replays to the Commis- audience could see replays showed Allan scored the bas- expira- sioner showing the basket should be ket with 2 tenths of a second tion of stated, allowed and not the 3 most on the clock. However, offi- time, "although important people—the refer- cials disagreed. They hud- Stern © ees calling the game! Ironi- dled after the shot for 30 "...although the subject has been considered from time to cally, the officials viewed the seconds to determine if they time. Until it does so, such is not the function of the replays in the locker after the were all in agreement. -

MA#12Jumpingconclusions Old Coding

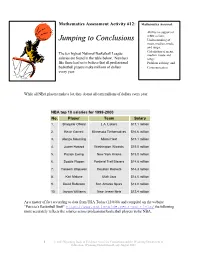

Mathematics Assessment Activity #12: Mathematics Assessed: · Ability to support or refute a claim; Jumping to Conclusions · Understanding of mean, median, mode, and range; · Calculation of mean, The ten highest National Basketball League median, mode and salaries are found in the table below. Numbers range; like these lead us to believe that all professional · Problem solving; and basketball players make millions of dollars · Communication every year. While all NBA players make a lot, they do not all earn millions of dollars every year. NBA top 10 salaries for 1999-2000 No. Player Team Salary 1. Shaquille O'Neal L.A. Lakers $17.1 million 2. Kevin Garnett Minnesota Timberwolves $16.6 million 3. Alonzo Mourning Miami Heat $15.1 million 4. Juwan Howard Washington Wizards $15.0 million 5. Patrick Ewing New York Knicks $15.0 million 6. Scottie Pippen Portland Trail Blazers $14.8 million 7. Hakeem Olajuwon Houston Rockets $14.3 million 8. Karl Malone Utah Jazz $14.0 million 9. David Robinson San Antonio Spurs $13.0 million 10. Jayson Williams New Jersey Nets $12.4 million As a matter of fact according to data from USA Today (12/8/00) and compiled on the website “Patricia’s Basketball Stuff” http://www.nationwide.net/~patricia/ the following more accurately reflects the salaries across professional basketball players in the NBA. 1 © 2003 Wyoming Body of Evidence Activities Consortium and the Wyoming Department of Education. Wyoming Distribution Ready August 2003 Salaries of NBA Basketball Players - 2000 Number of Players Salaries 2 $19 to 20 million 0 $18 to 19 million 0 $17 to 18 million 3 $16 to 17 million 1 $15 to 16 million 3 $14 to 15 million 2 $13 to 14 million 4 $12 to 13 million 5 $11 to 12 million 15 $10 to 11 million 9 $9 to 10 million 11 $8 to 9 million 8 $7 to 8 million 8 $6 to 7 million 25 $5 to 6 million 23 $4 to 5 million 41 3 to 4 million 92 $2 to 3 million 82 $1 to 2 million 130 less than $1 million 464 Total According to this source the average salaries for the 464 NBA players in 2000 was $3,241,895. -

STOP-DWI Holiday Classic Professional Alumni

STOP-DWI Holiday Classic Alumni and Professional Career Name High School Tournament Year College/Professional Charles Jones Bishop Ford (NY) 1992 College: Long Island Univ. Professional: LA Clippers/ Chicago Bulls/Houston Rockets Signed as a free agent with three NBA teams: Houston Rockets 1994-1997, Chicago Bulls 1998-1999 and Los Angeles Clippers 1999-2000. Bobby Lazor Norwich (NY) 1993 College: Syracuse/ Arizona State Professional: Has played at pro level in five different countries (USA, Japan, France, Italy & Puerto Rico). Eric Barkley Christ The King (NY) 1995 College: St. Johns Professional: Portland Trailblazers/San Antonio Spurs Drafted by the Portland Trail Blazers in the first round (28th pick overall) of the 2000 NBA draft…traded by the blazers with Steve Kerr and a 2003 second-round pick to the San Antonio Spurs for Antonio Daniels, Amal McCaskill and Charles Smith. Craig Speedy Claxton Christ The King (NY) 1995 College: Hofstra Professional: Philadelphia 76ers/ San Antonio Spurs/ Golden State Warriors/New Orleans Hornets/Atlanta Hawks Selected by Philadelphia 76ers in the first round (20th pick overall) of the 2000 NBA draft…traded by 76ers to the San Antonio Spurs in exchange for Mark Bryant and the draft rights to John Slamons and Rand Halcomb (June 26, 2002)…signed as a free agent by the Golden State Warriors July 23, 2003)…traded by Warriors with Dale Davis to New Orleans Hornets for Baron Davis (February 24, 2005)…signed as free agent by Atlanta hawks (July 12, 2006). Lamar Odom Christ The King (NY) 1995 College: Rhode Island Professional: LA Clippers Miami Heat/LA Lakers Selected after his sophomore season at Rhode Island by the Los Angeles Clippers in the first round (fourth pick overall) in the 1999 NBA draft…signed as a free agent by Miami Heat (August 26, 2003)…traded by Heat with Caron Butler, Brian Grant, a first –round draft choice and a second-round draft choice to Los Angeles Lakers for Shaquille O’Neal (July 14, 2004).