Lakeland Haute Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Windermere Guided Trail

Lake Windermere Guided Trail Tour Style: Guided Trails Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNLWI Trip Walking Grade: 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The Lake Windermere Trail is a circular walk that takes you on a lovely journey around Lake Windermere. The route takes in a mixture of lakeside paths and higher ground walking, all whilst experiencing some of the Lake District’s most stunning views. Lake Windermere is the largest lake in the Lake District and the largest in England. At 10½ miles long it has one end in the mountains and the other almost on the coast and is surrounded by very varied scenery. On the penultimate day we walk to the well known Bowness Bay. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The services of an HF Holidays' walks leader • All transport on walking days HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow lakeside paths and higher routes around Lake Windermere www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Take a boat trip on Lake Windermere • Views of the Coniston; Langdale and Ambleside Fells • Visit Bowness on Windermere TRIP SUITABILITY This Guided Walking /Hiking Trail is graded 3 which involves walks /hikes on well-defined paths, though often in hilly or upland areas, or along rugged footpaths. These may be rough and steep in sections and will require a good level of fitness. It is your responsibility to ensure you have the relevant fitness required to join this holiday. Fitness We want you to be confident that you can meet the demands of each walking day and get the most out of your holiday. -

Mountain Ringlet Survey Squares 2010

MOUNTAIN RINGLET SURVEY SQUARES 2014 – NOTES FOR SURVEYORS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- Please note: The following relates only to dedicated Mountain Ringlet searches. For casual records please use our website “Sightings” page where possible. Click on sightings report on: www.cumbria-butterflies.org.uk/sightings/ ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- We’d welcome surveys in any of the squares listed below, but are particularly interested in those marked * and +, ie where there have been recent positive sightings well away from known colonies or discovery of possible new colonies. The areas to be surveyed fall into 3 groups, in colour below, but also suffixed (1), (2) or (3) for those with black & white printers etc. 1. Grid squares that have previous positive sightings (shown in red) (1) 2. Grid squares adjacent to the above (shown in blue) (2) 3. Grid squares that are previously unrecorded but may have potential to hold Mountain Ringlet populations (shown in green) (3) The objective of these surveys is to try to determine the geographical spread of some known colonies, but also to survey areas that have suitable geology and which may hold previously unrecorded Mountain Ringlet populations. All the 1-km grid squares listed below lie in the 100-km square: NY AREA 1 - LANGDALE 2608 Martcrag Moor / Stake Pass (2) 2607 (north-east corner only) Part of Martcrag Moor (2) 2806 (northern edge) Raven Crag (1) 2807 Harrison Stickle (1) 2710 (eastern half only) -

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership Number: 3812 First Fell Climbed

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership number: 3812 First fell climbed: Coniston Old Man, 6 April 2003 Last fell climbed: Great End, 14 October 2019 I was a bit of a late-comer to the Lakes. My first visit was with my family when I was 15. We rented a cottage in Grange for a week at Easter. Despite my parents’ ambitious attempts to cajole my sister Cath and me up Scafell Pike and Helvellyn, the weather turned us back each time. I remember reaching Sty Head and the wind being so strong my Mum was blown over. My sister, 18 at the time, eventually just sat down in the middle of marshy ground somewhere below the Langdale Pikes and refused to walk any further. I didn’t return then until I was 28. It was my Dad’s 60th and we took a cottage in Coniston in April 2003. The Old Man of Coniston became my first summit, and I also managed to get up Helvellyn via Striding Edge with Cath and my brother-in-law Dave. Clambering along the edge and up on to the still snow-capped summit was thrilling. A love of the Lakes, and in particular reaching and walking on high ground, was finally born. Visits to the Lakes became more regular after that, but often only for a week a year as work and other commitments limited opportunities. A number of favourites established themselves: the Langdale Pikes; Lingmoor Fell; Catbells and Wansfell among them. I gradually became more ambitious in the peaks I was willing to take on. -

Grasmere & the Central Lake District

© Lonely Planet Publications 84 Grasmere & the Central Lake District The broad green bowl of Grasmere acts as a kind of geographical junction for the Lake District, sandwiched between the rumpled peaks of the Langdale Pikes to the west and the gentle hummocks and open dales of the eastern fells. But Grasmere is more than just a geological centre – it’s a literary one too thanks to the poetic efforts of William Wordsworth and chums, who collectively set up home in Grasmere during the late 18th century and transformed the valley into the spiritual hub of the Romantic movement. It’s not too hard to see what drew so many poets, painters and thinkers to this idyllic corner LAKE DISTRICT LAKE DISTRICT of England. Grasmere is one of the most naturally alluring of the Lakeland valleys, studded with oak woods and glittering lakes, carpeted with flower-filled meadows, and ringed by a GRASMERE & THE CENTRAL GRASMERE & THE CENTRAL stunning circlet of fells including Loughrigg, Silver Howe and the sculptured summit of Helm Crag. Wordsworth spent countless hours wandering the hills and trails around the valley, and the area is dotted with literary landmarks connected to the poet and his contemporaries, as well as boasting the nation’s foremost museum devoted to the Romantic movement. But it’s not solely a place for bookworms: Grasmere is also the gateway to the hallowed hiking valleys of Great and Little Langdale, home to some of the cut-and-dried classics of Lakeland walking as well as one of the country’s most historic hiking inns. -

Windermere Way

WINDERMERE WAY AROUND ENGLAND’S FINEST LAKE WINDERMERE WAY - WALKING SHORT BREAK SUMMARY The Windermere Way combines a delightful series of linked walks around Lake Windermere, taking in some of the finest views of the Lake District. Starting in the pretty town of Ambleside, the Windermere Way is made up of four distinct day walks which are all linked by ferries across the Lake. So you not only get to enjoy some wonderful walking but can also sit back and relax on some beautiful ferry journeys across Lake Windermere! The Windermere Way is a twin-centre walking holiday combining 2 nights in the lively lakeside town of Ambleside with 3 nights in the bustling Bowness-on-Windermere. Each day you will do a different walk and use the Windermere Ferries to take you to or from Ambleside or Bowness. From Ambleside, you will catch your first ferry to the lovely lakeside town of Bowness, where you will begin walking. Over the next four days you will take in highlights such as the magnificent views from Wansfell Pike, the glistening Loughrigg Tarn, and some delightful lakeshore walking. Most of the time you are walking on well maintained paths and trails and this is combined with some easy sections of road walking. Sometimes you will be climbing high up into the hills and at others you will be strolling along close to the lake on nice flat paths. Tour: Windermere Way Code: WESWW The Windermere Way includes hand-picked overnight accommodation in high quality B&B’s or Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday guesthouses in Ambleside and Bowness. -

Jennings Ale Alt

jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Grade: Time/effort 5, Navigation 3, Technicality 3 Start: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Finish: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Distance: 31.2 miles (50.2km) Time: 4 days Height gain: 3016m Maps: OS Landranger 90 (1:50 000), OS Explorer OL 4 ,5,6 & 7 (1:25 000), Harveys' Superwalker (1:25 000) Lakeland Central and Lakeland North, British Mountain Maps Lake District (1:40 000) Over four days this mini expedition will take you from the sublime pastoral delights of some of the Lake District’s most beautiful villages and hamlets and to the top of its best loved summits. On the way round you will be rewarded with stunning views of lakes, tarns, crags and ridges that can only be witnessed by those prepared to put the effort in and tread the fell top paths. The journey begins with a stay at the Inn on the Lake, on the pristine shores of Ullswater and heads for Grasmere and the Travellers Rest via an ancient packhorse route. Then it’s onto the Scafell Hotel in Borrowdale via one of the best viewpoint summits in the Lake District. After that comes an intimate tour of Watendlath and the Armboth Fells. Finally, as a fitting finish, the route tops out with a visit to the lofty summit of Helvellyn and heads back to the Inn on the Lake for a well earned pint of Jennings Cocker Hoop or Cumberland Ale. Greenside building, Helvellyn. jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Day 1 - inn on the lake, glenridding - the travellers’rest, grasmere After a night at the Inn on the Lake on the shores of Ullswater the day starts with a brief climb past the beautifully situated Lanty’s Tarn, which was created by the Marshall Family of Patterdale Hall in pre-refrigerator days to supply ice for an underground ‘Cold House’ ready for use in the summer months! It then settles into its rhythm by following the ancient packhorse route around the southern edge of the Helvellyn Range via the high pass at Grisedale Hause. -

Amanita Nivalis

Lost and Found Fungi Datasheet Amanita nivalis WHAT TO LOOK FOR? A white to greyish to pale grey/yellow-brown mushroom, cap 4 to 8 cm diameter, growing in association with the creeping Salix herbacea (“dwarf willow” or “least willow”), on mountain peaks and plateaus at altitudes of ~700+ m. Distinctive field characters include the presence of a volva (sac) at the base; a cylindrical stalk lacking a ring (although sometimes an ephemeral ring can be present); white to cream gills; striations on the cap margin to 1/3 of the radius; and sometimes remnants of a white veil still attached on the top of the cap. WHEN TO LOOK? Amanita nivalis, images © D.A. Evans In GB from August to late September, very rarely in July or October. WHERE TO LOOK? Mountain summits, and upland and montane heaths, where Salix herbacea is present (see here for the NBN distribution map of S. herbacea). A moderate number of sites are known, mostly in Scotland, but also seven sites in England in the Lake District, and four sites in Snowdonia, Wales. Many Scottish sites have not been revisited in recent years, and nearby suitable habitats may not have been investigated. Further suitable habitats could be present in mountain regions throughout Scotland; the Lake District, Pennines and Yorkshire Dales in England; and Snowdonia and the Brecon Beacons in Wales. Amanita nivalis, with Salix herbacea visible in the foreground. Image © E.M. Holden Salix herbacea – known distribution Amanita nivalis – known distribution Map Map dataMap data © National Biodiversity Network 2015 Network Biodiversity National © © 2015 GeoBasis - DE/BKG DE/BKG ( © 2009 ), ), Google Pre-1965 1965-2015 Pre-1965 1965-2014 During LAFF project Amanita nivalis Associations General description Almost always found with Salix herbacea. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

This Walk Description Is from Happyhiker.Co.Uk Red Pike And

This walk description is from happyhiker.co.uk Red Pike and High Stile Starting point and OS Grid reference Pay and display car park at Buttermere village (NY 173169) Ordnance Survey map OL4 The English Lakes – North Western Area Distance 7.7 miles Traffic light rating Introduction: This walk involves a very steep ascent up a scree gully on to aptly named Red Pike and an equally steep descent from Seat to Scarth Gap Pass. It is however a great ridge walk with contrasting views from the almost unreasonable prettiness of the Buttermere Valley to the north east and the rugged Scafell Range to the south east and a great profile of Pillar. There are also views down the usually deserted Ennerdale Valley. Depending on your fitness and enthusiasm, the walk could easily be lengthened to include Haystacks but after the ascent and descents mentioned above this might be a climb too far! Start: The walk starts from the car park at Buttermere village (NY 173169) where you will need plenty of change to meet the cost! There are toilets here too. Walk back down the car park road and turn right in front of the Fish Hotel and follow the sign for Buttermere Lake down a broad track. Where this forks, take the left fork. At the lake, turn right and follow the line of the lakeshore towards the trees. As you get to the corner of the lake, cross over the stream on the little bridge and take the attractive route through the trees on the steep stone stepped path (NY 173163). -

Spring 12 Newsletter

Spring 2012 Well it has been a busy few months in the Venables household, thankyou for all your Upcoming cards and messages. We look forward to bringing Isaac on first Shot trip in the near Trips future to join all the other Shotlets. March, Glenridding Thanks Nigel Venables Friday 16th - Sunday 18th March, Glenridding, Lake District June, Cynwyd A welcome return to the well equipped Bury Hut. As most people know it is located l000ft up a valley on one of the main routes to Helvellyn accessed via a steep concrete track. Apparently, during last winter’s heavy snow some groups staying here had quite an epic just getting up to its front doors. Who knows what SHOT will encounter this year? October 12-14th Ignoring the detritus of the extensive lead Llanwrtyd Wells mining that once occurred in this valley our Stonecroft Lodge base is supremely sited for all manner of routes Details to up and around the Helvellyn Range above our follow...but it is heads to the west - and with a starting point at Dave and l000ft it is just a short huff and a puff away. Yvonne’s 40th Birthday Nethermost Pike, Dollywagon, Catstyy Cam, hopefully there Raise, Stybarrow Dodd, Fairfield, St. Sunday will be lots of Crag and of course Helvellyn itself are all well cake known to mums and dads, and in a short time the Shotlets as well. Striding Edge will surely test the nerves of any parent. More pedestrian and touristy options abound lower down in Patterdale and Ullswater where purses and wallets can be quickly lightened. -

Lecturer in Forestry Institute of Science, Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies

Lecturer in Forestry Institute of Science, Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies Location: Ambleside Starting Salary: £33,797 with incremental progression to £38,017 Post Type: Full Time Contract Type: Permanent Release Date: Friday 25 June 2021 Closing Date: 23.59 hours BST on Sunday 25 July 2021 Interview Date: Thursday 05 August 2021 Reference: XX037921 The Institute of Science, Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies is seeking to recruit a Lecturer in Forestry and woodland management with strong links to the sector. Details of the post can be found at: XX037921 Lecturer in Forestry - Jobs at University of Cumbria We are the University of Cumbria, a place where people are at the heart of all we do, where enriching the lives of our students, staff and the communities we serve means we make a difference that really matters. Now is a very exciting time to be joining us because we are delivering a new strategic plan focused on making the most of our three most valuable assets; People, Place and Partnerships, to become a catalyst for economic well-being for our region, nationally and internationally. We are seeking innovative, creative, high quality researchers, and scholars to foster a culture of exploration, discovery and intellectual challenge that generates international recognition, respect and engagement. The Institute of Science, Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies is one of five Institutes within the University. It is a busy and vibrant Institute which has strong links with a number of professional bodies and employers which is reflected in the high level of employment our students enjoy. The Institute is split across two sites, Ambleside and Carlisle, to suit the academic portfolio and delivery needs of the programmes. -

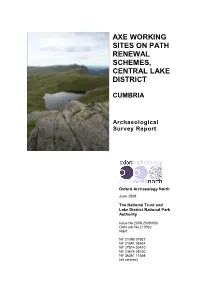

Axe Working Sites on Path Renewal Schemes, Central Lake District

AXE WORKING SITES ON PATH RENEWAL SCHEMES, CENTRAL LAKE DISTRICT CUMBRIA Archaeological Survey Report Oxford Archaeology North June 2009 The National Trust and Lake District National Park Authority Issue No 2008-2009/903 OAN Job No:L10032 NGR: NY 21390 07921 NY 21891 08551 NY 27514 02410 NY 23676 08230 NY 36361 11654 (all centred) Axe Working Sites on Path Renewal Schemes, Cumbria: Archaeological Survey Report 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................ 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ 3 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of the Project......................................................................... 4 1.2 Objectives..................................................................................................... 4 2. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Project Design .............................................................................................. 6 2.2 The Survey ................................................................................................... 6 2.4 Archive......................................................................................................... 7 3. TOPOGRAPHIC AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................ 8