Tracing the Tradition of Comic and Constructive Criticism by Jesters in Imperial Courts of India Rajpal Jangir Abstract: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Akbar and Birbal – Reunion

10. AKBAR AND BIRBAL – REUNION One day, when Akbar and Birbal were in discussion, Birbal happend to pass a harmless comment about Akbar's sense of humour. But Emperor Akbar was in a foul1 mood and took great offense to this remark. He asked Birbal, his court jester, friend and confidant to not only leave the palace but also to leave the walls of the city of Agra. Birbal was terribly hurt at being banished2. A couple of days later, Akbar began to miss his best friend. He regretted3 his earlier decision of banishing him from the court. He just could not do without Birbal and so sent out a search party to look for him. But Birbal had left the town without letting anybody know of his destination4. The soldiers searched high and low but were unable to find him anywhere. Then, one day a wise saint came to visit the palace accompanied by two of his disciples5. The disciples claimed that their teacher was the wisest man to walk the earth. Since Akbar was missing Birbal terribly6, he thought it would be a good idea to have a wise man that could keep him company. But he decided that he would first test the holy man's wisdom. The saint had bright sparkling7 eyes, a thick beard and long hair. The next day, when they came to visit the court, Akbar informed the holy man that, since he was the wisest man on the earth, he would like to test him. All his ministers would put forward questions and if his answers were satisfactory he would be made a minister. -

Portrait of Tansen

Portrait of Tansen Moti Chandra There is a genuine desire among music lovers to discover the person ality of a great artist. Stray details of his life, lively anecdotes, stirring or evocative moments during a performance go to build a picture of the man. And the externals of his personality are indicated by portraits, which, for all their limitations, afford a glimpse of the maestro. The first six Moghul rulers prized learning and culture, and, above all, the art of miniature painting. While Humayun took the initial steps to develop this branch, it was Akbar who laid the actual foundations of a proper school of this art form. The city built by Akbar at Fatehpur Sikri was the ideal locale for a community of craftsmen and aesthetes devoted to the pursuit of the arts. That remarkable chronicler of the times, Abul Fazl, has in his two works, the Akbar Namah and the Aini Akbari, left us a faithful account of the varied interests of Akbar's court. Akbar attracted a wealth of talent towards himself. The Aini Akbari has a special chapter on the art of painting and mentions Akbar's personal interest in the atelier at his court. The master painters were the two Persians, Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali; the rest of the artists were mainly Hindus. The painters concentrated on two branches of the art of miniature: book illustration and portraiture. In drawing a portrait, the artist's primary concern was to seize a likeness. Thus we have a pictorial record of the Nine Jewels who added lustre to Akbar's court. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Folk and Feudal Crossover at the Imperial Court Rajpal PhD Research Scholar Department of English Indira Gandhi University Meerpur, Rewari (HR) & Professor Nikhilesh Yadav Department of English Indira Gandhi University Meerpur, Rewari (HR) Abstract The present paper is based on two anecdotes of Birbal and Tenali Raman‟s entry in the royal courts of Akbar and Krishan Dev Rai. The researchers have attempted to bring to fore the folk and feudal cross over that takes place in the imperial court. The paper implicitly attempts to problematize the whole idea of representation which seems less effective than the meritocracy that seems at full swing in both the narratives undertaken for research in this paper. The researchers find that the feudal mode of governance provides a democratic space to the folk to enter the ministerial body through wit. On the contrary, the contemporary democratic mode of governance provides this space through „representation‟ which is subjected to other factor excluding „wit‟ or sagacity or prudence. Key Words: Anecdote, folk fools, feudal, governance, jesterdom, comic criticism, meritocracy, democracy, folk wit, critique In the present paper, the researchers undertake a close comparative critical reading of anecdotes of Akbar-Birbal and King Krishan Dev Rai-Tenali Raman with specific emphasis primarily on two aspects: (a) how these folk fools enter the royal courts and (b) how these courtiers treat the irrational in a so called „democratic space‟ protecting themselves. The idea of comparing the feudal mode of governance with our contemporary mode of governances, aims at developing a critique of the contemporary one. -

Mulla Nasruddin in Cinema

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 2 April 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 MULLA NASRUDDIN IN CINEMA Mona Agnihotri PhD Scholar Centre of Russian Studies (CRS) School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies (SLL&CS) Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, India Abstract: Mulla Nasruddin is a folk hero. His tales are popular the world over. It is believed that he originally belonged to Turkey. His tales are short and humorous. But through humor these tales teach important life- lessons which people otherwise fail to learn. This paper portrays Mulla Nasruddin in a new role – that of a film hero. During the Soviet period many of his tales were made into films in the Central Asian Republics of the erstwhile Soviet Union, mainly Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Some of his films are described in this paper. The material for this paper has been collected from the Internet sources especially Youtube.com which has these Mulla Nasruddin full-length feature films. The links to these films have been provided as footnotes in the paper. Keywords: Mulla Nasruddin, Films, Soviet Union, Central Asian Republics. Otto von Bismarck ones quoted that – “Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”1 Mulla Nasruddin’s version, who is considered to be a ‘wise fool’2, goes one step further than this, saying – “However, a wise fool is generous enough to let others learn from his failures.” The moment one hears the name Mulla Nasruddin, an image of an old man with a long beard riding backwards on his donkey appears before one’s eyes. -

Democracy's Handmaiden: Humour: in Today's India, We Need More of a Funny Bone in Our Public Life

Indiatimes | The Times of India | The Economic Times | Like 37K AYURVEDIC GARGLE FOR 1/2/3 Bed Apartments near PAIN AND INFECTION-FR… Hebbal Blogs THROATAd KOFOL Ad Prestige Group Home Blogs Times View Readers' Blog Times Evoke City India World Entertainment Sports Lifestyle Environment Spirituality Q&A Foreign Media Business ... News » Blogs » Edit Page Blogs » Democracy’s handmaiden: Humour: In today’s India, we need more of a funny bone in our public life WRITE FOR TOI BLOGS Democracy’s handmaiden: Humour: In today’s India, we need more of a funny bone in our public life July 11, 2020, 7:45 AM IST Rohini Nilekani in Voices | Edit Page, India, World | TOI Book your home @ ₹50,000 only Experience the joy of connecting with nature at Earth & Essence. In these dark times, there is no harm in easing up with some sharp humour. Like the With 1.5 acre Earth club coronavirus, humour is infectious, but can spread much needed joy. The world over, AUTHOR social media is lighting up with witty memes around the pandemic. Bumbling politicians have been prime targets, and especially President Donald Trump. “Calm down, Rohini Nilekani everyone,” reads one meme, “A six-time bankrupted reality TV star is handling the situation.” MOST POPULAR MOST DISCUSSED MOST READ Encounter Pradesh – Where Vikas Dubey is shot dead before trial On Removal of SPG Cover to the Gandhis and the Spectacle of Petulant Politics Stepping back: India, China agree to disengage. But New Delhi must keep its guard up India must work with other countries to erode China’s economic influence The problem of distory: History is distorted by every group. -

Nasreddin Hodja/ Nebi Özdemir; Trans: M

THE PHILOSOPHER’S PHILOSOPHER NNASREDDINASREDDIN HHODJAODJA by Nebi ÖZDEMİR © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3311 Handbook Series 14 ISBN: 978-975-17-3565-2 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Özdemir, Nebi The Philosopher’s Philosopher Nasreddin Hodja/ Nebi Özdemir; Trans: M. Angela Roome.- Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2011. 172 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3311. Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 14) ISBN: 978-975-17-3565-2 Selected Bibliography I. title. II. Roome, M. Angela. III. Series. 927 Translated by M. Angela Roome Printed by Grafiker Ltd. Şti. Oğuzlar Mahallesi 1. Cadde 1396. Sokak No:6, 06520 Balgat-Ankara Tel: 0 312 284 16 39 • Faks: 0 312 284 37 27 www.grafiker.com.tr Photographs Grafiker Ltd. Şti. Archive, Akşehir Municipality Archive. First Edition Print run: 5000. Printed in Ankara in 2011. CONTENTS A. NASREDDIN HODJA’S HISTORICAL IDENTITY .......5 a. Nasreddin Hodja’s Historical Identity and Related Documentation .........................................5 b. Nasreddin Hodja’s Name ................................... 10 c. Nasreddin Hodja’s Life and Family ........................ 12 B. ANECDOTES ABOUT NASREDDIN HODJA ..........15 C. NASREDDIN HODJA’S WORLD OF WIT ...............17 D. NASREDDIN THE OMNISCIENT ........................34 E. THE NASREDDIN HODJA CANON ......................63 F. NASREDDIN HODJA PUBLICATIONS ...................77 G. NASREDDIN HODJAS TRADITIONAL HUMOUR ....83 a. Humour In the Press and Literature ...................... 83 b. Th eatre ........................................................ 85 c. Cinema and Animation ..................................... 89 d. Radio, Television and the Internet ........................ 92 H. SELECTIONS FROM THE NASREDDIN HODJA CANON ........................................................ 109 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................. -

Siegel, Lee. Laughing Matters: Comic Tradition in India. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987

180 BOOK REVIEWS non-Indo-European traditions, can all give deep insights into the transformation of the Indo-European ideology of the three functions in its Indian milieu. Particularly interesting in the last regard is Hiltebeitel,s ongoing work on the relationships between the <( Indo-European ” aspects of the Mahdbhdrata and the folk cults of Draupadi in their South Indian cultural matrix, which is an amalgam of Indo-Aryan and non-Indo- Aryan elements (See Alf H i l t e b e i t e l , 1988). Dubuisson should take his cue from Hiltebeitel, who proves that Dumezilian theory need not be an ideological straitjacket, but can instead be the stimulating starting point for exploration in Indian texts and phenomena. Attractive as structural paradigms are in their symmetry and neatness, they cannot yet compare to the scholarly challenge of the living, breathing, changing nature of a text in its cultural environment. REFERENCES CITED: H i l t e b e i t e l , Alf 1976 The ritual of battle: Krishna in the Mahdbhdrata. Ithaca; Cornell Uni versity Press. 1988 The cult of Draupadi’ volume I. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Indira Viswanathan Peterson Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, M A 01075 USA Siegel, Lee. Laughing Matters: Comic Tradition in India. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987. xviii+497 pages. Biblio graphic essay, illustrations, index of Indian texts and authors cited, sub ject index. Cloth US$40.25; ISBN 0-226-75691-2. Did you hear the one about the monkey that fucked the Buddha in the ear? Not likely, if you don’t read Sanskrit and are forced to rely upon the puritanical translations of 19th and 20th century indologists, whose concern was to retain the modern Western spiritualism of great Eastern traditions. -

1.2 Who's the Greatest – Answers

J K Academy www.jkacademypro.com Grade: 6 Name of the Student ________________________________ 1.2 Who’s the Greatest – Answer Meanings: patron of art and culture : a person who appreciates, supports and encourages art and culture flog : beat someone hard, especially with a whip agitated : disturbed incur our displeasure : make me angry in a proper fix : in a tight corner, in a difficult situation vast: of very great size or area empire: a group of people or nations under an emperor’s rule. generations: a group of people living at a particular time. stunned: astonished, surprised, amazed moustache: facial hair growing on between a man’s upper lip and nose. lashes: to strike or beat with a whip whip: to beat with a belt, strap or thin object like a cane or rod offending: action disliked by others opinion: a personal view favours: a kind act compete: try to do better than the other curious: eager to learn or know banish: to expel or drive away someone from a country. POINTERS 1. Listen to the stories carefully, as your teacher reads them aloud. Note down the new words, ideas or concepts. Discuss them in the class. 2. Guess the meaning of the following words and phrases : untold wealth – a large amount of wealth closest to the Emperor’s heart – Emperor’s favourite grave offence – serious crime banish - to expel or drive away someone from a country. www.jkacademypro.com 3. Say with reasons, whether the following statements are true or false. (a) Akbar wanted to punish the person who pulled his moustache. -

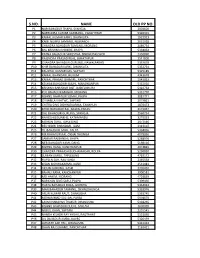

S.No. Name Old Pp No

S.NO. NAME OLD PP NO. P1 NAR BAHADUR THAPA, SYANGJA 2003600 P2 NARENDRA KUMAR KAMBANG, PANCHTHAR 5326301 P3 KAMAL KUMAR KARKI, DHANKUTA 1922923 P4 KAMI NURPU TAMANG, NUWAKOT 2031928 P5 CHANDRA BAHADUR TAMANG, MORANG 2089734 P6 BAL KRISHNA GHIMIRE, JHAPA 5334032 P7 RATNA BAHADUR SHRESTHA, SINDHUPALCHOK 2350890 P8 RAJENDRA PRASAD RIJAL, BHAKTAPUR 2511800 P9 CHANDRA BAHADUR GURUNG, NAWALPARASI 5333678 P10 KHIR BAHADUR KARKI, DHANKUTA 5333734 P11 KAUSHAL KUMAR DAS, SAPTARI 5325189 P12 KAMAL BHANDARI, RUKUM 4343678 P13 KAMAL PRASAD GHIMIRE, PANCHTHAR 1943823 P14 KESHAB BAHADUR MAJHI, MAKAWANPUR 5332010 P15 KRISHNA BAHADUR BIST, DADELDHURA 5322764 P16 KUL BAHADUR MAGAR, MORANG 5331770 P17 BISHNU BAHADUR SOMAI, PALPA 3081721 P18 CHHABILA KHATWE, SAPTARI 2073821 P19 CHITRA SING BISHWOKARMA, TANAHUN 1870473 P20 BHIM BAHADUR RAI, NAWALPARASI 2172957 P21 DAL BAHADUR GURUNG, SYANGJA 2560734 P22 RAMESH BISUNKHE, KATHMANDU 3279933 P23 MOHAN OJHA, TAPLEJUNG 2473546 P24 BED NIDHI BHANDARI, ILAM 3313107 P25 TIL BAHADUR SARU, PALPA 5334026 P26 BIR BAHADUR RAI, OKHALDHUNGA 4078036 P27 SANKAR RAJBANSHI, JHAPA 5268976 P28 NEB BAHADUR KAMI, DANG 5198116 P29 BISHNU RANA, KANCHANPUR 4074891 P30 CHANDRA PRAKASH BUDHAMAGAR, ROLPA 5290850 P31 SUMAN LIMBU, TAPLEJUNG 4719172 P32 RUPSEN SAH, RAUTAHAT 2365558 P33 KISAN BISHWAKARMA, KASKI 2531481 P34 ARJUN GURUNG, KASKI 2709420 P35 BAHALI RANA, KANCHANPUR 3900581 P36 MO HAKIM, MORANG 4729639 P37 NARAYAN SING SARU, PALPA 5309460 P38 HASTA BAHADUR ROKA, GORKHA 5334044 P39 MAN BAHADUR TAMANG, OKHALDHUNGA 5333976 P40 ARUN