View / Download Pdf Version of BPJ 63

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seborrheic Dermatitis: an Overview ROBERT A

Seborrheic Dermatitis: An Overview ROBERT A. SCHWARTZ, M.D., M.P.H., CHRISTOPHER A. JANUSZ, M.D., and CAMILA K. JANNIGER, M.D. University of Medicine and Dentistry at New Jersey-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey Seborrheic dermatitis affects the scalp, central face, and anterior chest. In adolescents and adults, it often presents as scalp scaling (dandruff). Seborrheic dermatitis also may cause mild to marked erythema of the nasolabial fold, often with scaling. Stress can cause flare-ups. The scales are greasy, not dry, as commonly thought. An uncommon generalized form in infants may be linked to immunodeficiencies. Topical therapy primarily consists of antifungal agents and low-potency steroids. New topical calcineurin inhibitors (immunomodulators) sometimes are administered. (Am Fam Physician 2006;74:125-30. Copyright © 2006 American Academy of Family Physicians.) eborrheic dermatitis can affect patients levels, fungal infections, nutritional deficits, from infancy to old age.1-3 The con- neurogenic factors) are associated with the dition most commonly occurs in condition. The possible hormonal link may infants within the first three months explain why the condition appears in infancy, S of life and in adults at 30 to 60 years of age. In disappears spontaneously, then reappears adolescents and adults, it usually presents as more prominently after puberty. A more scalp scaling (dandruff) or as mild to marked causal link seems to exist between seborrheic erythema of the nasolabial fold during times dermatitis and the proliferation of Malassezia of stress or sleep deprivation. The latter type species (e.g., Malassezia furfur, Malassezia tends to affect men more often than women ovalis) found in normal dimorphic human and often is precipitated by emotional stress. -

Hyperhidrosis: Sweating out the Details

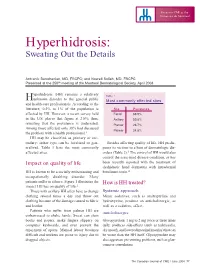

Focus on CME at the Université de Montréal Hyperhidrosis: Sweating Out the Details Antranik Benohanian, MD, FRCPC; and Nowell Solish, MD, FRCPC Presented at the 250th meeting of the Montreal Dermatological Society, April 2003 yperhidrosis (HH) remains a relatively Table 1 Hunknown disorder to the general public Most commonly affected sites and health-care professionals. According to the literature, 0.5% to 1% of the population is Site Prevalence affected by HH. However, a recent survey held Facial 68.9% in the U.S. places that figure at 2.8%; thus, Axillary 50.8% revealing that the prevalence is underrated. Plantar 28.7% Among those affected, only 38% had discussed Palmar 24.8% the problem with a health professional.1 HH may be classified as primary or sec- ondary; either type can be localized or gen- Besides affecting quality of life, HH predis- eralized. Table 1 lists the most commonly poses its victims to a host of dermatologic dis- affected sites. orders (Table 2).3 The control of HH would also control the associated disease condition, as has Impact on quality of life been recently reported with the treatment of dyshidrotic hand dermatitis with intradermal HH is known to be a socially embarrassing and botulinum toxin.4 occupationally disabling disorder. Many patients suffer in silence. Figure 1 illustrates the How is HH treated? impact HH has on quality of life.2 Those with axillary HH often have to change Systemic approach clothing several times a day and throw out Minor sedatives, such as amitriptyline and clothing because of the damage caused to fabric hydroxyzine, produce an anticholinergic, as and leather. -

Scalp Eczema Factsheet the Scalp Is an Area of the Body That Can Be Affected by Several Types of Eczema

12 Scalp eczema factsheet The scalp is an area of the body that can be affected by several types of eczema. The scalp may be dry, itchy and scaly in a chronic phase and inflamed (red), weepy and painful in an acute (eczema flare) phase. Aside from eczema, there are a number of reasons why the scalp can become dry and itchy (e.g. psoriasis, fungal infection, ringworm, head lice etc.), so it is wise to get a firm diagnosis if there is uncertainty. Types of eczema • Hair clips and headgear – especially those containing that affect the scalp rubber or nickel. Seborrhoeic eczema (dermatitis) is one of the most See the NES booklet on Contact Dermatitis for more common types of eczema seen on the scalp and hairline. details. It can affect babies (cradle cap), children and adults. The Irritant contact dermatitis is a type of eczema that skin appears red and scaly and there is often dandruff as occurs when the skin’s surface is irritated by a substance well, which can vary in severity. There may also be a rash that causes the skin to become dry, red and itchy. on other parts of the face, such as around the eyebrows, For example, shampoos, mousses, hair gels, hair spray, eyelids and sides of the nose. Seborrhoeic eczema can perm solution and fragrance can all cause irritant contact become infected. See the NES factsheets on Adult dermatitis. See the NES booklet on Contact Dermatitis for Seborrhoeic Dermatitis and Infantile Seborrhoeic more details. Dermatitis and Cradle Cap for more details. -

Toward a Better Understanding of the Spectrum of Morphea

STUDY ONLINE FIRST High Frequency of Genital Lichen Sclerosus in a Prospective Series of 76 Patients With Morphea Toward a Better Understanding of the Spectrum of Morphea Virginie Lutz, MD; Camille Francès, MD, PhD; Didier Bessis, MD; Anne Cosnes, MD; Nicolas Kluger, MD; Julien Godet, PhD; Erik Sauleau, PhD; Dan Lipsker, MD, PhD Objective: To compare the frequency of genital lichen diagnosis was 54 (13-87) years. Forty-nine patients had sclerosus (LS) in patients with morphea with that of con- plaque morphea, 9 had generalized morphea, and 18 had trol patients. linear morphea. Three patients (3%) in the control group and 29 patients (38%) with morphea had LS (odds ra- Design: A prospective multicenter study. tio,19.8; 95% CI, 5.7-106.9; PϽ.001). Twenty-two pa- tients with plaque morphea (45%) and only 1 patient with Setting: Four French academic dermatology depart- linear morphea (6%) had associated genital LS. ments: Strasbourg, Montpellier, Tenon Hospital Paris, and Henri Mondor Hospital Cre´teil. Conclusions: Genital LS is significantly more frequent in patients with morphea than in unaffected individu- Patients: Patients were recruited from November 1, 2008, als. Forty-five percent of patients with plaque morphea through June 30, 2010. Seventy-six patients with mor- have associated LS. Complete clinical examination, in- phea and 101 age- and sex-matched controls, who un- cluding careful inspection of genital mucosa, should there- derwent complete clinical examination, were enrolled. fore be mandatory in patients with morphea because geni- tal LS bears a risk of evolution into squamous cell Interventions: A complete clinical examination and, if deemed necessary, a cutaneous biopsy. -

Skin Conditions and Related Need for Medical Care Among Persons 1=74 Years United States, 1971-1974

Data from the Series 11 NATIONAL HEALTH SURVEY Number 212 Skin Conditions and Related Need for Medical Care Among Persons 1=74 Years United States, 1971-1974 DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 79-1660 U.S, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Md. November 1978 NATIONAL CENTIER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS DOROTHY P. RICE, Director ROBERT A. ISRAEL, Deputy Director JACOB J. FELDAMN, Ph.D., Associate Director for Amdy.sis GAIL F. FISHER, Ph.D., Associate Director for the Cooperative Health Statistics System ELIJAH L. WHITE, Associate Director for Data Systems JAMES T. BAIRD, JR., Ph.D., Associate Director for International Statistics ROBERT C. HUBER, Associate Director for Managewzent MONROE G. SIRKEN, Ph.D., Associate Director for Mathematical Statistics PETER L. HURLEY, Associate Director for Operations JAMES M. ROBEY, Ph.D., Associate Director for Program Development PAUL E. LEAVERTON, Ph.D., Associate Director for Research ALICE HAYWOOD,, Information Officer DIVISION OF HEALTH EXAMINATION STATISTICS MICHAEL A. W. HATTWICK, M.D., Director JEAN ROEERTS, Chiej, Medical Statistics Branch ROBERT S. MURPHY, Chiej Survey Planning and Development Branch DIVISION OF OPERATIONS HENRY MILLER, ChieJ Health -Examination Field Operations Branch COOPERATION OF THE U.S. BUREAU OF THE CENSUS Under the legislation establishing the National Health Survey, the Public Health Service is authorized to use, insofar as possible, the sesw?icesor facilities of other Federal, State, or private agencies. In accordance with specifications established by the National Center for Health Statis- tics, the U.S. Bureau of the Census participated in the design and selection of the sample and carried out the household interview stage of :the data collection and certain parts of the statis- tical processing. -

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

An Ayurvedic Approach in the Management of Darunaka (Seborrhoeic Dermatitis): a Case Study

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.10; Issue: 4; April 2020 Website: www.ijhsr.org Case Study ISSN: 2249-9571 An Ayurvedic Approach in the Management of Darunaka (Seborrhoeic Dermatitis): A Case Study Kumari Archana1, D.B. Vaghela2 1PhD Scholar, 2Assosiate Professor, Shalakyatantra Department, Institute for Post Graduate Teaching and Research in Ayurveda, Gujarat Ayurved University, Jamnagar, India. Corresponding Author: Kumari Archana ABSTRACT Darunaka is a Kapalagataroga but Acharya Sushruta has described this disease as a Kshudraroga due to the vitiation of Vata and Kapha Doshas with symptoms like Kandu (itching on scalp), Keshachyuti (falling of hair), Swapa(abnormalities of touch sensation on scalp), Rookshata (roughness or dryness of the scalp) and Twaksphutana (breaking or cracking of the scalp skin). Seborrhoeic Dermatitis, an irritative disease of the scalp in which shedding of dead tissue from the scalp with itching sensation is the cardinal feature which can be correlated with Darunaka. It has been reported that Seborrhoeic Dermatitisaffect about 4% of the population, and dandruff (which is mild seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp) can affect almost half of all adults. It can start at any time after puberty and is slightly commoner in men. It can result in social or self-esteem problems. A 56 yr old male patient from Jamnagar came to OPD of ShalakyaTantra, with chief complaint of ShirahKandu (itching on scalp), Rukshata (dryness on scalp), TwakSphutana (cracks in the skin) with blood mixed watery oozing, KeshaChyuti (hair fall). In this case Ayurvedic formulation of ArogyavardhiniVati (orally), TriphalaChurna (orally), ManjisthadiKwatha (orally), YashtiChurna mixed with coconut hair oil as external application followed by washing the hair with a Kwatha (decoction) of TriphalaYavkut and ShuddhaTankana. -

“The Red Face” and More Clinical Pearls

“The Red Face” and More Clinical Pearls Courtney R. Schadt, MD, FAAD Assistant Professor Residency Program Director University of Louisville Associates in Dermatology I have no disclosures or conflicts of interest Part 1: The Red Face: Objectives • Distinguish and diagnose common eruptions of the face • Recognize those with potential implications for internal disease • Learn basic treatment options Which patient(s) has an increased risk of hypertension and hyperlipidemia? A B C Which patient(s) has an increased risk of hypertension and hyperlipidemia? A Seborrheic Dermatitis B C Psoriasis Seborrheic Dermatitis Goodheart HP. Goodheart's photoguide of common skin disorders, 2nd ed, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2003. Copyright © 2003 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Seborrheic Dermatitis • Erythematous scaly eruption • Infants= “Cradle Cap” • Reappear in adolescence or later in life • Chronic, remissions and flares; worse with stress, cold weather • Occurs on areas of body with increased sebaceous glands • Unclear role of Malassezia; could be immune response; no evidence of overgrowth Seborrheic Dermatitis Severe Seb Derm: THINK: • HIV (can also be more diffuse on trunk) • Parkinson’s (seb derm improves with L-dopa therapy) • Other neurologic disorders • Neuroleptic agents • Unclear etiology 5MinuteClinicalConsult Clinical Exam • Erythema/fine scale • Scalp • Ears • Nasolabial folds • Beard/hair bearing areas Goodheart HP. Goodheart's photoguide of common skin disorders, 2nd ed, Lippincott • Ill-defined Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia -

LICHEN SCLEROSUS Lichen Sclerosus (Sometimes Called Lichen

LICHEN SCLEROSUS Lichen Sclerosus (sometimes called lichen sclerosus at atrophicus, or LS&A) is a skin condition that is most common on the vulva of older women who have gone through menopause. However, lichen sclerosus sometimes affects girls before puberty, as well as young adult women, and the penis of uncircumcised males. In females, lichen sclerosus can affect rectal skin also. Only rarely does lichen sclerosus affect skin outside the genitalia, and this is usually the back, chest or abdomen. Lichen sclerosus almost never appears on the face or hands. The causes of lichen sclerosus are not completely understood, but a main cause is an over-active immune system. The immune system, that part of the body that fights off infection, becomes over-active and attacks the skin by mistake. Why this happens is not known. Lichen sclerosus typically appears as white skin that is very itchy. The skin is also fragile, so rubbing and scratching can cause breaks, cracks and bruises that hurt. Sexual activity is often painful or impossible. Untreated, lichen sclerosus can cause scarring and, occasionally, narrowing of the opening of the vagina in women. In boys and men, the foreskin can scar to the head of the penis. Untreated lichen sclerosus is also associated with skin cancer of the vulva in about one in thirty women. There is also an increased risk of skin cancer of the penis in men. These risks can be lowered when lichen sclerosus is well-controlled. Irritating creams, unnecessary medication, soaps and over washing should be avoided. Washing should be limited to once daily with clear water only. -

Therapies for Common Cutaneous Fungal Infections

MedicineToday 2014; 15(6): 35-47 PEER REVIEWED FEATURE 2 CPD POINTS Therapies for common cutaneous fungal infections KENG-EE THAI MB BS(Hons), BMedSci(Hons), FACD Key points A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of common fungal • Fungal infection should infections of the skin and hair is provided. Topical antifungal therapies always be in the differential are effective and usually used as first-line therapy, with oral antifungals diagnosis of any scaly rash. being saved for recalcitrant infections. Treatment should be for several • Topical antifungal agents are typically adequate treatment weeks at least. for simple tinea. • Oral antifungal therapy may inea and yeast infections are among the dermatophytoses (tinea) and yeast infections be required for extensive most common diagnoses found in general and their differential diagnoses and treatments disease, fungal folliculitis and practice and dermatology. Although are then discussed (Table). tinea involving the face, hair- antifungal therapies are effective in these bearing areas, palms and T infections, an accurate diagnosis is required to ANTIFUNGAL THERAPIES soles. avoid misuse of these or other topical agents. Topical antifungal preparations are the most • Tinea should be suspected if Furthermore, subsequent active prevention is commonly prescribed agents for dermatomy- there is unilateral hand just as important as the initial treatment of the coses, with systemic agents being used for dermatitis and rash on both fungal infection. complex, widespread tinea or when topical agents feet – ‘one hand and two feet’ This article provides a practical approach fail for tinea or yeast infections. The pharmacol- involvement. to antifungal therapy for common fungal infec- ogy of the systemic agents is discussed first here. -

Natural Remedies for Dandruff

Natural Remedies for Dandruff Before you consider treating dandruff, you must first understand what it is, so that you can be sure you are suffering from dandruff and not a more serious condition. Dandruff is small pieces of dead skin found in a person’s hair. Dandruff can be mild and hardly noticeable, but in some cases can be itchy and the scalp can be red and inflamed. Dandruff can be a chronic condition or related to certain variables such as extreme temperatures and weather changes. If your dandruff is severe, the best option is to be seen by your dermatologist. If, however, it is mild there are several natural remedies that are thought to help improve dandruff. 1. Apple Cider Vinegar Possibly one of the best natural remedies for dandruff, rinsing your scalp with a half water half apple cider vinegar mixture can help decrease flakiness. Apple Cider Vinegar will remove dead skin cells and unclog pores. It also has strong anti-fungal properties, which can help fight off any dandruff caused by fungus on the scalp. Rinse your scalp with the mixture and leave it overnight. Wash your hair the next day with a gentle shampoo. 2. Chamomile Tea Chamomile is very soothing and safe for sensitive skin. It can help with redness and irritation. Brew three sachets of chamomile tea and be sure to allow ample time for the tea to cool. Once the tea has cooled to about room temperature, apply the liquid to the scalp and massage. Allow this to sit for several hours and then rinse thoroughly. -

PE2342 Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic Dermatitis What is seborrheic Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition. It causes redness, dermatitis? scaling, or flaky patches in infants, teens and adults. What parts of the • Scalp (this is known as dandruff, or cradle cap in infants) body are usually • Eyebrows affected? • Eyelids • Ears • Nose • Skin fold areas (such as armpits or thighs) What causes The cause of seborrheic dermatitis is not known. Some believe that it is seborrheic caused by an overgrowth of yeast. It is not related to what you eat and it is dermatitis? not contagious. Stress and sickness often make seborrheic dermatitis symptoms worse, but they do not cause it. Symptoms can get better or worse for no reason. What are the Symptoms include: symptoms of • Redness seborrheic • Itching dermatitis? • Scaly patches on your skin that may look greasy or oily • Scales or flakes on the head or in the hair • Crusty yellow flakes on the eyelids or eyelashes What are the There is no cure for seborrheic dermatitis, but there are ways to keep it treatment options? under control. Treatment options for seborrheic dermatitis depend on what part of the body is showing symptoms. Skin Seborrheic dermatitis of the skin can usually be controlled by putting on steroid or antifungal creams to the skin (topical). These medicines help with the redness and itching of your child’s skin. Check with your child’s healthcare provider before giving your child any type of topical medicine. They will help you determine which treatment option would be best. 1 of 2 To Learn More Free Interpreter Services • Dermatology • In the hospital, ask your nurse.