The Blood Sacrifice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Post-Apocalypse and Human Power in Cormac Mccarthy's the Road

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations from 2009 2015-08-05 A world-maker's will: the post-apocalypse and human power in Cormac McCarthy's The Road Jackson, Alexander David http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/662 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons A World-Maker's Will: The Post-Apocalypse and Human Power in Cormac McCarthy's The Road A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University Thunder Bay, ON In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English By Alexander David Jackson May 2nd 2014 Jackson 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... v Post-Apocalyptic Power: First Steps .............................................................................................. 1 The Apocalypse and its Alternate Forms ........................................................................................ 6 Situating Scholarship on The Road............................................................................................... 15 Making a World in the Ruins........................................................................................................ 20 The Man's Moral Imperatives -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Studies in Romans

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 1957 Studies in Romans R. C. Bell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bell, R. C., "Studies in Romans" (1957). Stone-Campbell Books. 470. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/470 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. STUDIESIN ROMANS R.C.BELL F IRM FOUNDATION PUBLISHING HOUSE AUSTIN , TEXAS COPYRIGHT, 1887 FIRM FOUNDATION PUBLISHING HOU SE LESSON 1 Though Romans was written near the close of Paul's mis sionary ministry, reasonably, because of its being a fuller 1-1.ndmore systematic discussion of the fundamentals of Christianity than the other Epistles of the New Testament, 'it is placed before them. Paul's earliest writings, the Thes salonian letters, written some five years before Romans, rea sonably, because they feature Christ's second coming and the end of the age, are placed, save the Pastoral Epistles and Philemon, last of his fourteen Epistles. If Mordecai, with out explicit evidence, believed it was like God to have Esther on the throne at a most crucial time (Esther 4 :14), why should it be "judged incredible" that God had some ~hing to do with this arrangement of his Bible? The theme of the Bible from Eden onward is the redemp tion of fallen man. -

Today We Have This Powerful Story of the Raising of the Widow's Son from the Dead. We Know There Are a Couple of Other Exampl

Today we have this powerful story of the raising of the widow’s son from the dead. We know there are a couple of other examples in the Scriptures of Jesus raising people from the dead. Of course, the story of the raising of Lazarus and the story of the raising of the daughter of Jairus. But this raising story, you’ll notice, is a little different. In this story no one is asking Jesus for help. For Lazarus, Martha says “If you had been here, my brother would not have died.” Jairus says, “My daughter is at the point of death. Please, come lay your hands on her that she may get well and live.” Jesus sets on His own initiative and in this we see His great compassion. Let’s look at the scene a little closer. The one who died was the only son of a widow. So she was alone. Her husband had died, and now her only son had died, so she has the terrible grief of losing her son after already having lost her husband. She has the prospect now of being alone, and on top of this, in those days women didn’t really work for income. So now she has to be completely dependent on the charity of others to live. Maybe she now would even have to be reduced to begging. The Lord sees all this going on. The exact scripture we heard was: “When the Lord saw her, He was moved with pity for her.” So we see the Lord’s great compassion here. -

Vulnerable Victims: Homicide of Older People

Research and Issues NUMBER 12 • OCTOBER 2013 Vulnerable victims: homicide of older people This Research and Issues Paper reviews published literature about suspected homicide of older people, to assist in the investigation of these crimes by Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC) or police investigators. The paper includes information about victim vulnerabilities, nature of the offences, characteristics Inside and motives of offenders, and investigative and prosecutorial challenges. Victim vulnerabilities .................................... 3 Although police and CMC investigators are the paper’s primary audience, it will Homicide offences ........................................ 3 also be a useful reference for professionals such as clinicians, ambulance officers Investigative challenges ................................ 8 or aged care professionals who may encounter older people at risk of becoming Prosecutorial challenges ............................. 10 homicide victims. Crime prevention opportunities .................. 14 This is the second paper produced by the CMC in a series on “vulnerable” victims. Conclusion .................................................. 15 The first paper, Vulnerable victims: child homicide by parents, examined child References .................................................. 15 homicides committed by a biological or non-biological parent (CMC 2013). Abbreviations ............................................. 17 Appendix A: Extracts from the Criminal Code (Qld) ................................................. -

A Practitioner's Guide to Culturally Sensitive Practice for Death and Dying Texas Long Term Care Institute

A Practitioner's Guide to Culturally Sensitive Practice for Death and Dying Prepared By Merri Cohoe, BSW Sue Ellen Contreras, BSW Debra Sparks, BSW Texas Long Term Care Institute College of Health Professions Southwest Texas State University San Marcos, Texas TLTCI Series Report 02-2 April 2002 Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes only. Please credit the Texas Long Term Care Institute. Additional copies may be obtained from the Texas Long Term Care Institute, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, Texas, 78666 Phone: 512-245-8234 FAX 512-245-7803. Email: L [email protected] Website: http://LTC-Institute.health.swt.edu CWe; w.auU eJw [o;~ tJus; ~fl/ [o;OU/tI~iIv~4tAwv~, ~, and~tuJi4i1vOW1l~. CWe; w.auU ~ eJw [0; ~ aft tJuv Soci.at CW~ wJuy Iuwe; ~ t/te; uuuJ; I<w USJ. ~it is; 0W1I ~ widv [0; ~ tAerrv p;uuul. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....... ........................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .......................... ...... ..... ... ............. .............. .... 6 African Methodist Episcopal .................. , ................. " ........... , .... ... .. .. 7 American Evangelical. .. 8 Anglican .................................................................................... 9 Anglican Catholic Church ......... " . " ................................................ '" 10 Assemblies of God .............. , ..... .................... ................ ....... .......... 11-12 Atheism..... .................. ....... .................... ............... -

The Human Encounter with Death

The Human Encounter With Death by STANISLAV GROF, M.D. & JOAN HALIFAX, PH.D. with a Foreword by ELISABETH KÜBLER-ROSS, M.D D 492 / A Dutton Paperback / $3.95 / In Canada $4.75 Stanislav Grof, M.D., and Joan Halifax, Ph.D., have a unique authority and competence in the interpretation of the human encounter with death. Theirs is an extraordin ary range of experience, in clinical research with psyche- delic substances, in cross-cultural and medical anthropology, and in the analysis of Oriental and archaic literatures. Their pioneering work with psychedelics ad ministered to individuals dying of cancer opened domains of experience that proved to be nearly identical to those al ready mapped in the "Books of the Dead," those mystical visionary accounts of the posthumous journeys of the soul. The Grof/Halifax book and these ancient resources both show the imminent experience of death as a continuation of what had been the hidden aspect of the experience of life. —Joseph Campbell The authors have assisted persons dying of cancer in tran scending the anxiety and anger around their personal fate. Using psychedelics, they have guided the patients to death- rebirth experiences that resemble transformation rites practiced in a variety of cultures. Physician and medical anthropologist join here in recreating an old art—the art of dying. —June Singer The Human Encounter With Death is the latest of many re cent publications in the newly evolving field of thanatology. It is, however, a quite different kind of book—one that be longs in every library of anyone who seriously tries to un derstand the phenomenon we call death. -

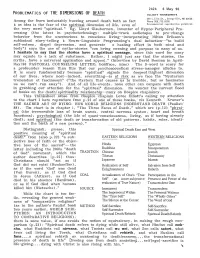

Problematics of the Dimensions of Death

2424 6 May 90 PROBLEMATICS OF THE DIMENSIONS OF DEATH ELLIOTT THINKSHEETS 309 L.Eliz.Dr., Craigville, MA 02636 Among the fears ineluctably buzzing around death both as fact Phone 508.775.8008 & as idea is the fear of the spiritual dimension of life, even of Noncommercial reproduction permitted the very word "spiritual." Eg, Lloyd Glaubermen, inventor of Hypno-Peripheral Pro- cessing (the latest in psychotechnology: multiple-track audiotapes to pre-change behavior from the unconscious to conscious living--incorporating Milton Erikson's subliminal story-telling & Neuro-Linguistic Programming's dual induction--"to build self-esteem, dispel depression, and generate a healing effect in both mind and body") says the use of myths-stories "can bring meaning and purpose to many of us. I hesitate to say that the stories have a spiritual message , since this word for many may equate to a lack of substance. Rather, I might just say that the stories, the myths, have a universal application and appeal." (Interview by David Beeman in April- May/90 PASTORAL COUNSELING LETTER; boldface, mine) The S-word is scary for a profounder reason than this that our psychoacoustical stress-manager alludes to. It is scary fundamentally because "spiritual" signals the deepest/highest dimension of our lives, where most--indeed, everything--is at risk as we face the "Mysterium tremendum et fascinosum" ("the Mystery that causes us to tremble, but so fascinates us we can't run away"). And of all life-events, none other can compare with death in grabbing our attention for the "spiritual" dimension. No wonder the current flood of books on the death/spirituality relationship--many on Hospice chaplaincy. -

Death in the Spirituality of the Desert Daniel Lemeni

The Untimely Tomb: Death in the Spirituality of the Desert Daniel Lemeni UDC: 27-788"03/05" D. Lemeni 27-35"03/05" West University of Timişoara Review Faculty of Teology Manuscript received: 22. 10. 2016. Str. Intrarea Sabinei, nr.1, ap. 6 Revised manuscript accepted: 07. 02. 2017. 300422 Timişoara, Timiş, Romania DOI: 10.1484/J.HAM.5.113743 [email protected] In this paper we will explore the “practice of death” in the spirituality of the desert. e paper is divided into two sections. Section 1 explores the desert as place of the death. e monk has symbolized this death by locating his existence in the desert, because the renunciation of secular life led the monk to regard himself as dead. Section 2 points out depictions of monks as dead or entombed. We will examine here the role played by “daily dying” in the Life of Antony. Antony the Great characterizes his life as a kind of “death”, because he lives as though dying each day. In other words, the monk, though not actually dead, eectively dies each day. is kind of “death” (daily dying) contains the seeds of later ascetic tradition on a “practice of death”. Keywords: death, Desert Fathers, Late Antiquity, monasticism, Antony the Great. INTRODUCTION growth of monasticism in fourth-century Egypt has long been recognized as one of the most significant and alluring The withdrawal from the world is the most powerful moments of early Christianity. In the withdrawal from the metaphor to describe the mortification in the spirituality mainstream of society and culture to the stark solitude of of the desert. -

From Ritual Crucifixion to Host Desecration 25 Derived the Information He Put to Such Disastrous Use at Lincoln

Jewish History 9Volume 12, No. 1 9Spring 1998 From Ritual Cruc,ifixion to Host Desecration: Jews and the Body of Christ Robert C. Stacey That Jews constitute a threat to the body of Christ is the oldest, and arguably the most unchanging, of all Christian perceptions of Jews and Judaism. It was, after all, to make precisely this point that the redactors of the New Testament reassigned resPonsibility for Jesus's crucifixion from the Roman governor who ordered it, to an implausibly well-organized crowd of "Ioudaioi" who were alleged to have approved of it. 1 In the historical context of first-century CE Roman Judea, it is by no means clear who the New Testament authors meant to comprehend by this term loudaioi. To the people of the Middle Ages, however, there was no ambiguity, ludaei were Jews; and the contemporary Jews who lived among them were thus regarded as the direct descendants of the Ioudaioi who had willingly taken upon themselves and their children the blood of Jesus that Pilate had washed from his own hands. 2 In the Middle Ages, then, Christians were in no doubt that Jews were the enemies of the body of Christ. 3 There was considerably more uncertainty, however, as to the nature and identity of the body of Christ itself. The doctrine of the resurrection imparted a real and continuing life to the historical, material body of Christ; but it also raised important questions about the nature of that risen body, and about the relationship between that risen body and the body of Christian believers who were comprehended within it. -

Let Me Distill What Rosemary Ruether Presents As the Critical Features Of

A Study of the Rev. Naim Ateek’s Theological Writings on the Israel-Palestinian Conflict The faithful Jew and Christian regularly turn to the texts of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament for wisdom, guidance, and inspiration in order to understand and respond to the world around them. Verses from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are regularly employed in the discussion of the Israel-Palestine conflict. While the inspiration for justice and righteousness on behalf of all who are suffering is a hallmark of both scriptures, the present circumstance in the Land of Israel poses unique degrees of difficulty for the application of Biblical text. The prophets of old speak eternal and absolute ideas, in the circumstance and the vernacular of their time. God speaks. Men and women hear. The message is precise. The challenge of course is to extract the idea and to apply it to the contemporary circumstance. The contemporary State of Israel is not ancient Israel of the First Temple period, 11th century BCE to 6th century BCE, nor Judea of the first century. Though there are important historical, national, familial, faith, and communal continuities. In the absence of an explicit word of God to a prophet in the form of prophecy we can never be secure in our sense that we are assessing the contemporary situation as the ancient scriptural authors, and, more importantly, God, in Whose name they speak, would have us do. If one applies to the State of Israel biblical oracles addressed to the ancient people Israel, one has to be careful to do so with a sense of symmetry. -

Of Contemporary Popular Music

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 11 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Winter 2009 Article 2 2009 The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music Tracy Reilly Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Tracy Reilly, The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music, 11 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 335 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol11/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music: An Alternative to the Legal Regulation of Death-Metal and Gangsta-Rap Lyrics Tracy Reilly* ABSTRACT The purpose of this Article is to contribute to the volume of legal scholarship that focuses on popular music lyrics and their effects on children. This interdisciplinary cross-section of law and culture has been analyzed by legal scholars, philosophers, and psychologists throughout history. This Article specifically focuses on the recent public uproar over the increasingly violent and lewd content of death- metal and gangsta-rap music and its alleged negative influence on children. Many legal scholars have written about how legal and political efforts throughout history to regulate contemporary genres of popular music in the name of the protection of children's morals and well-being have ultimately been foiled by the proper judicial application of solid First Amendment free-speech principles.