A Study on Occupational Status & Utilization Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the High Court of Kerala at Ernakulam Present The

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE RAJA VIJAYARAGHAVAN V WEDNESDAY, THE 28TH DAY OF APRIL 2021 / 8TH VAISAKHA, 1943 WP(C).No.33596 OF 2019(Y) PETITIONERS: 1 THE KODUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.R.1523, VALIYAD, KODUR P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 676 504, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY K.MOHANADASAN. 2 PULAMANTHOLE SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F 1565, PULAMANTHOLE P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 323, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY ABOOBACKER. 3 THE ELAMKULAM SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F.1536, KUNNAKKAVU P.O., MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 340, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY T.ARUNKUMAR. 4 THE PUNNAPPALA SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.F.928, P.O.NADUVATH, VIA WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY SATHIANATHAN K.P. 5 THE PORUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.357, P.O.CHATHANGOTTUPURAM, WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY RAGHUNATH E. 6 THE CHOKKAD SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.602, P.O.CHOKKAD, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 352, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY SAJEEVAN NAIR V.P. 7 THE WANDOOR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.387, P.O.WANDOOR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 679 328, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY UMMER A.P. 8 THE TRIPRANGODE SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.1890, P.O.TRIPANGODE, TIRUR, MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, PIN - 676 108, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY P.V.SURESH. 9 THE NIRAMARUTHUR SERVICE CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD.NO.M.612, KUMARANPADI P.O., PIN - 676 109, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY CHANDRAN V.K. -

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT GENERAL CATEGORY Sl

NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION (NMMSE)-2019 (FINAL LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES) MALAPPURAM DISTRICT GENERAL CATEGORY Sl. Caste ROLL NO Applicant Name School_Name No Category 1 42191650108 THANVEERA K P General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 2 42191740040 FATHIMA NIDA N General P K M M H S S Edarikkode , EDARIKODE 3 42191580133 RANIYA I P General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 4 42191680372 MOHAMMED SINAN V K General T S S Vadakkangara , vadakkangara 5 42191760362 AYISHA HENNA K General G. H. S Pannippara , PANNIPPARA 6 42191770018 DILSHAN K General SOHS Areacode , Areekode 7 42191820084 AYISHA ZIYA E P General G G V H S S Wandoor , wandoor 8 42191750228 FATHIMA HUDA KANNATTY General IUHSS Parappur , Parappur 9 42191580122 MUHAMMED SALAH A General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 10 42191650029 MOHAMMED SHAMIL M General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 11 42191750303 AHMED SABIQUE K General P K M M H S S Edarikkode , EDARIKODE 12 42191610381 SHIFNA M General G V H S S Makkaraparamba , Makkaraparamba 13 42191580131 NIHAL AHMAD E T General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 14 42191640123 ADHILA P General P.P.M.H.S.S. Kottukkara , KOTTUKKARA 15 42191620135 MUBEEN N General T S S Vadakkangara , vadakkangara 16 42191590136 ADIL SHAN P C General GHSS POOKKOTTUR , Aravankara,Pookottur 17 42191730306 SHIFANA PULLAT General P P T M Y H S S Cherur , VENGARA 18 42191620144 SABEEHA P General T S S Vadakkangara , vadakkangara 19 42191590151 FATHIMA SULHA P General GHSS POOKKOTTUR , Aravankara,Pookottur 20 42191620108 RINSHAD C P General G H S S Kadungapuram , KADUNGAPURAM 21 42191640160 FATHIMA HIBA K General P.P.M.H.S.S. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

List of Participants

Centre for Academic Leadership and Education Management (CALEM) (Under the Scheme of PMMMNMTT HRD Ministry, Govt. of India, New Delhi) Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh – 202002 UP (India) List of Participants ONLINE ACADEMIC LEADERSHIP COURSE FOR TEACHERS (From 28.01.2021 to 03.02.2021) Theme: Online Teaching/Learning/Evaluation Project Coordinator : Professor A.R. Kidwai, Director, UGC HRDC, AMU, Aligarh Project Co-coordinator : Dr. Faiza Abbasi, Assistant Professor, UGC HRDC, AMU, Aligarh Course Coordinator : Mr. Rafeequeali Mundodan, E.M.E.A. College of Arts & Science, Kondotti, Malappuram (Kerala) Host Institution : E.M.E.A. College of Arts & Science, Kondotti, Malappuram (Kerala) S. Name & Designation Institutional Address Residential Address Mobile No. & email M / F SC/ST/ No. ID OBC/M/G 1. Ms. Saleema K M.E.S. Ponnani College, 8848197993 F/M Assistant Professor Ponnai South, Malappuram [email protected] (Kerala) m 2. Ms. Aneesath M E.M.E.A. College of Arts & Padippan kunnu house 8129158545 F/OBC Assistant Professor Science, Kondotty, pookkottur 676517 [email protected] Malappuram (Kerala) m 3. Ms. Amla. K. K E.M.E.A. College of Arts & Kolakkoden 9633160071 F/OBC Assistant Professor Science, Kondotty, amlarahmath @gmail. Malappuram (Kerala) com 4. Ms. Faseela NK E.M.E.A. College of Arts & Kuruvangath H 9744629799 F/OBC Assistant Professor Science, Kondotty, Pulliparamba Po nkfaseelahassan@gm Malappuram (Kerala) Chelembra - 673634 ail.com 5. Ms. Nusrath K Department of Computer Konnola House, Kolar 9846997113 F/M Head Science, M.E.S. Ponnani Road, Downhill P O, nusrathk.mescs@gma College, Ponnai South, Malappuram-676519 il.com Malappuram (Kerala) 6. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Kerala State Electricity Board

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (Incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1956) Power System Engineering CIN: U40100KL2011SGC027424 Office of the Director (Transmission & System Operation) Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 004, Kerala Phone: +91 471 2514528, 9446008567 Fax: 0471 2444738 : [email protected], [email protected], Website: www.pse.kseb.in. No.: D(T&SO)/PSE/SCPSP/2016-17/413 Date: 01.09.2016 To, 1) Sri. Pardeep Jindal Chief Engineer (SP&PA-1) System Planning & Project Appraisal Committee Central Electrical Authority Sewa Bhavan, R.K Puram New Delhi – 110066. 2) The Chief Operating Officer Power Grid Corp. of India Ltd “Saudamini”, Plot no.2, Sector – 29 Gurgaon 122001, Hariyana. Sir, Sub: Implementation of 400kV Madakkathara – Malaparamba - Nallalam feeder – Reg. Ref: Nil. Sanction was accorded in the 39th meeting of the Standing Committee on Power System Planning for Southern Region, for the construction of 400kV Madakkathara – Areekode and 220kV Madakkathara – Malaparamba - Nallalam feeder, utilizing the RoW of existing 220/110kV feeders as 400/220kV multi-voltage multi circuit feeders by KSEB Ltd. The sanctioned scheme is designed with the following elements: 1. Construction of two additional 400kV bays at existing 400kV Substation, Madakathara. 2. Construction of additional 220kV bays at Madakathara, Malaparamba and Nallalam. 3. Construction of a 220kV Switching Station at Mavoor (Ambalaparamba) with ten line bays for providing a pooling point by LILO of following 220kV feeders: Areakode – Nallalam D/c Areekode – Kaniampetta S/c and Madakathara – Areekode D/c. Registered Office: Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 004, Kerala. Website: www.kseb.in As per the agreed scheme, it is proposed to import the power from existing 400kV substation at Madakathara. -

No. G2-2188/2020/KATS Kerala Anti Terror Squad, Malappuram Dated

No. G2-2188/2020/KATS Kerala Anti Terror Squad, Malappuram Dated. 05-10-2020 TENDER NOTICE The Superintendent of Police ( Operations) KATS ,Police Depatment, Government of Kerala invites online bids from reputed manufacturers/ authorized dealers or reputed vendors for RECHARCHABLE LED FLASH LIGHTS (20 Nos) The bidders should comply with the following general conditions in addition to the additional conditions of the tender. General 1. The Bidder should be a reputed Original equipment Manufacturer (OEM) or authorized dealer of OEM, who is having an Authorization Certificate from the OEM to participate in the tender floated by Kerala Police. certificate from the OEM for sales and service, to be produced . 2. One bidder cannot represent two suppliers/OEMs or quotes on their behalf in a particular tender. 3. The OEM/Bidder should have a well equipped service centre functioning in India (preferable in Kerala) to cater to immediately after sales requiremnent, copy of Service Centre details must be enclosed along with Tender document. (Preferably bidder should have a service centre in Kerala/south India). 4. A reputed vendor can participate in the tender provided the vending outfit is functioning in the market for at lesat 10 years. 5. The Bidder should have valid GST registration. Copy of GST registration certificate should be enclosed along with the tender. 6. The bidder should have valid PAN/Taxation Index Number. Copy of PAN/Taxation Index Number allocation letter should be enclosed along with the tender. 7. The Bidder must fulfil the following minimum qualification criteria to prove the techno commercial competance and submit the documents in support thereof: 1. -

List of Blood Donors ,Emea College Nss Unit

LIST OF BLOOD DONORS ,EMEA COLLEGE NSS UNIT Sl Blood Mobile/What No. Full Name Group sApp No Address District Panchayat Sex Palliyali House, Melangadi P.O., 1 Mohammed Rafi P A +ve 9048991347 Kondotty Malappuram Kondotty Male Tk House Pariyarakkal Kavanur Po Malappuram 2 Muhammed Murshid Tk O +ve 7025575639 673639 Malappuram Kavanur Male 3 Muhammed Naseef Nm O +ve 8891479212 Narrikkottu Mecheri Malappuram Mooniyur Male 4 Najiya Nasrin. V O +ve 9562169553 Cholayilmattil(H) Puthur Pallikkal(Po) 673636 Malappuram Pallikkal Female 5 Muhammed Afnan.P A +ve 7558088665 Kanyavil (H) Panambra Po Thenhipalam 673636 Malappuram Thenhipalam Male Poochengal Kunnath (H) Pantherangadi Po Vm Bazar 6 Aneesha Binshi B +ve 7994153665 676306 Malappuram Tirurangadi Female 7 Ramees M O +ve 9747559185 Machingal House Mundappalam,Kondotty Malappuram Kondotty Male 8 Mohammed Jaseem P O +ve 8129005189 Kuyyam Kandathil (H) Kottukkara, Karimukku, Kondotty (P. O) 673638 Malappuram Kondotty Male Karattil(House) Pathanapuram , Areacode , Valillapuzha (Po) Keezhuparam 9 Anas.Karattil O +ve 9895287221 Pin .673 639 Malappuram b Male 10 Muhammed Anshif K B +ve 8129400691 Vilakkupparambil (H)Kuzhimanna(P.O) Malappuram Kuzhimanna Male 11 Abdulla Midhlaj Et O +ve 8156935760 Chalilthodi House Karaparamba Pulpetta Po Pin 676123 Malappuram Pulpetta Male 12 Muhammed Mubashir Ka O - ve 9446810826 Kudkkil Aramanakkotta(H) Balathilpuray Kizhisseri Malappuram kuzhimanna Male 13 Muhammed Binfas.K A +ve 8593922041 Manchalamkunn House Ozhukur Po Malappuram Morayur Male 14 Fawaz Anarath B +ve 9995767152 Anarath House Kozhikode Villiappally Male 15 Mohammed Fahiz C T A +ve 7593906596 Cheruthodika (H) Calicut Airport (Po) Kondotty Malappuram Kondotty Male 16 Naheema Kp A +ve 9847258429 Kodali Puthen Veetil House Mongam Malappuram Pookkottur Female parappanang 17 Afna C O +ve 9526665684 Chekkali House Parappanangadi Malappuram adi Female Perinkadakkatt House P.O Mampuram 18 Salva B +ve 6238918567 Pin 676306 Malappuram A.r nagar Female Thottiyil Kollencheri (H) Manalippuzha. -

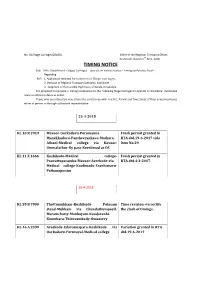

TIMING NOTICE Sub:- Mvs

No. G1/Stage Carriages/2018/D. Office of the Regional Transport Officer, Kozhikode, Dated 17 th April, 2018 TIMING NOTICE Sub:- MVs. Department – Stages Carriages - operate on various routes – Timing conference fixed – Regarding. Ref:- 1. Application received from owners of Stage carriages. 2. Decision of Regional Transport Authority, Kozhikode 3. Judgment of Honourable High Court of Kerala, Ernakulam. It is proposed to convene a timing conference for the following Stage Carriages to operate on the below mentioned route on different dates at 11AM. Those who are interested may attend the conference with the R.C, Permit and Time Sheet of their concerned buses either in person or through authorized representative. 25 -4-2018 KL 10 R 2919 Mavoor -Oorkadavu -Perumanna - Fresh permit granted in Manakkadavu-Pantheerankavu-Mathara- RTA dtd.19-6-2017 vide Athani-Medical college via Kovoor- item No.29 Ummalathur-By pass-Keezhmad as OS KL 11 X 1666 Kozhikode -Medical college - Fresh permit granted in Poovattuparamba-Mavoor-Areekode-via RTA dtd.4-3-2017. Medical college-Koolimadu-Eranhimavu- Pathanapuram 26-4-2018 KL 59 B 7900 Thottumukkam -Kozhikode Palayam Time revision –to rectify stand-Mukkam via Chundathumpoyil- the clash of timings . Maramchatty-Mankayam-Koodaranhi- Koombara-Thiruvambady-Omassery KL 46 A 2399 Areekode -Edavannapara -Kozhikode via Variation granted in RTA Oorkadavu-Peruvayal-Medical college dtd.19-6-2017 2-5-2018 KL 13 N 3441 Thusharagiri -Kozhikode via Variation granted in RTA Chembukadavu-Nooramthode dtd.19-6-2017 WPC No.5757/2018 -

Hospital Name District City/Town Pincode Address a a Rahim

Hospital Name District City/Town Pincode Address A A Rahim Memorial District Hospital Kollam 691008 Near Taluk Kachery Chinnakada Kollam Community Health Centre Cheruvathur Cheruvathur Po Chc Cheruvathur Kasaragod Cheruvathur 671313 Kasaragod 671313 Chc Chungathara Malappuram Chungathara 679334 Community Health Centre, Chungathara Chc Edapal Malappuram Edapal 679576 Edappal Community Health Centre, Chc Edavanna Malappuram Edavanna 676541 Chembakuth,Edavanna P.O Chc Edayarikkapuzha Kottayam Edayarikkapuzha 686541 Chc Edayirikkapuzha Chc Kalady Ernakulam Mattoor 683574 Community Health Centre Kalady Chc Kalikavu Malappuram Kalikavu 676525 Chc Kalikavu,Kalikavu,676525 Chc Kallara Thiruvananthapuram 500001 Chc Kanyakulangara Thiruvananthapuram Trivandrum 695615 Kanyakulangara Po,Trivandrum Chc Katampazhipuram Palakkad Katampazhipuram 678633 Katamapzhipuram Chc Kesavapuram Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor 695601 Community Health Centre Kesavapuram Chc Kumarakom Kottayam Kottayam 686563 Chc Kumarakom Chc Meenangdi Wayanad 673591 Chc Moothakunnam Ernakulam Paravour 683516 Chc Moothakunnam Chc Mukkam Kozhikode 673602 Chc Mukkam, Chc Narikkuni Kozhikode Kozhikode 673585 Chc Narikkuninarikkuni P.Okozhikode Chc Nenmara Palakkad Nenmara 678508 Chc Nenmara,Nenmara(Po)-678508 Chc Nilamel Nilamel Po Kollam Kerala Chc Nilamel Kollam Nilamel 691535 691535 Chc Omanur Malappuram Edavannapara 673645 Chc Omanur, Ponnad, Edavannapara Chc Panamaram Wayanad Panamaram 670721 Community Health Centre Chc Pandappilly Ernakulam Pandappilly 686672 Chc Pandappilly Chc -

Accused Persons Arrested in Malappuram District from 28.02.2021To06.03.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 28.02.2021to06.03.2021 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 63/2021 U/S BIPIN B MOOZHIYAN 05-03- 118(I) OF KP NAIR, SUB 73, HOUSE CHATTIPAR MALAPPUR BAILED BY 1 ALAVI SAIDALVI 2021 AT ACT & 6 R/W INSPECTOR MALE CHATTIPARAMBA AMBA AM POLICE 08:50 HRS 24 COTPA MALAPPURA MALAPPURAM ACT M BIPIN B 62/2021 U/S MEPPALLIKKAD,HA KAVUNGAL 04-03- NAIR, SUB 41, 13,63 MALAPPUR BAILED BY 2 BABURAJAN AYYAPPAN JIYARPALLI,MALAP ,MALAPPUR 2021 AT INSPECTOR MALE KERALA AM POLICE PURAM AM 16:40 HRS MALAPPURA ABKARI ACT M MANAYANTHODI BALACHAND (H), KOTTAMAD, 06-03- 69/2021 U/S 28, RAN IS, SI OF BAILED BY 3 SAJEER HUSSAIN CHEUR PO, VENGARA 2021 AT 118(I) OF KP VENGARA MALE POLICE POLICE VENGARA, 12:15 HRS ACT VENGARA PS MALAPPURAM. KAPRATTU BALACHAND BALAKRISH NARIYANCHERI 05-03- ANIL 40, 68/2021 U/S RAN IS, SI OF BAILED BY 4 NA HOUSE, VENGARA 2021 AT VENGARA KUMAR MALE 151 CRPC POLICE POLICE PANIKKAR CHOLAKUND, 11:55 HRS VENGARA PS PARAPPUR POOVANCHERI BALACHAND 05-03- 67/2021 U/S ABDUL 35, HOUSE, RAN IS, SI OF BAILED BY 5 HAMSA VENGARA 2021 AT 118(I) OF KP VENGARA JALEEL MALE KANNATTIPADI POLICE POLICE 10:50 HRS ACT P.O , VENGARA VENGARA PS KOLAMBIL 06-03- 66/2021 U/S MOIDEEN 60, HOUSE,CHENEKKA VASLSAN, GSI BAILED BY 6 KUNHEEN VENGARA 2021 AT 118(I) OF KP VENGARA -

19-11-2018 to 18-11-2024 Topic PERCEPTION and MEMORY: REPRESENTING HOLOCAUST and NAQBA in the POST MILLENIAL WORLD CINEMA Centre Department of English, PTM Govt

File Ref.No.220742/RESEARCH-B-ASST-2/2018/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract DoR - Ph.D. Programme 2018 - Registration to Ph.D. in English - Ms. Farsanah Moossa Kappil - Department of English, PTM Govt. College, Perinthalmanna as Research Centre - Granted - Orders issued Directorate of Research U.O.No. 14118/2018/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 03.12.2018 Read:-(1) Notification No.142314/DOA-ASST-3/2014/Admn dated 21-11-2017, (2) The application for Registration forwarded by The Principal, PTM Govt. College, Perinthalmanna, (3) Rules & Regulations for Ph.D Programme, 2016, (4) U.O. No. DOR/B3/Ph.D/General/2011 dated 31-05-2012, (5) Memo No. 220742/RESEARCH-B-ASST-2/2018/Admn dated 13-11-2018. ORDER As per papers read above, sanction has been accorded to grant registration to Ms. Farsanah Moossa Kappil for pursuing Ph.D. Programme in English for a period of six years as a Full-time research scholar with effect from 19- 11-2018 as per the Rules & Regulations referred to as 3 above. The details of Supervising Teacher, Topic, Category, Mode of Research, etc., are given as under; Name & Address of the Candidate Ms. Farsanah Moossa Kappil, Valiyapeediyekkal (H), Methalangadi, Edavanna PO, Malappuram - 676541 Name & Address of the Guide Dr. Abida Farooqui, Assistant Professor, Department of English, PTM Govt. College, Perinthalmanna Stream Full-Time Subject & Faculty English, Language & Literature Period 19-11-2018 to 18-11-2024 Topic PERCEPTION AND MEMORY: REPRESENTING HOLOCAUST AND NAQBA IN THE POST MILLENIAL WORLD CINEMA Centre Department of English, PTM Govt. College, Perinthalmanna Fellowship/Sponsorship Nil NB: The scholar shall attend the Research Centre and submit progress report with attendance details to this office once in every six months.