Daniel Eccleston of Lancaster 1745-1821: a Man Not Afraid to Stand on the Shoulders of Giants Carolyn Downs University of Lancaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973 Transcribed from index books within the Lancaster County Archives collection Name of Organization Book Page Office 316th Infantry Association 1 57 Prothonotary 316th Infantry Association 3 57 Prothonotary A. B. Groff & Sons 4 334 Recorder of Deeds A. B. Hess Cigar Co., Inc. 2 558 Recorder of Deeds A. Buch's Sons' & Co. 2 366 Recorder of Deeds A. H. Hoffman Inc. 3 579 Recorder of Deeds A. M. Dellinger, Inc. 6 478 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Denver, PA) 6 13 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Miller Hess & Co. Inc.) (merger) R-53 521 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Landis Inc. 6 554 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Snader & Company 3 3 Recorder of Deeds A. S. Kreider Shoe Manufacturing Co. 5 576 Recorder of Deeds A. T. Dixon Inc. 5 213 Recorder of Deeds Academy Sacred Heart 1 151 Recorder of Deeds Acme Candy Pulling Machine Co. 2 290 Recorder of Deeds Acme Metal Products Co. 5 206 Recorder of Deeds Active Social & Beneficial Association 5 56 Recorder of Deeds Active Social and Beneficial Association 2 262 Prothonotary Actor's Company 5 313 Prothonotary Actor's Company (amendment) 5 423 Prothonotary Adahi Hunting Club 5 237 Prothonotary Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster 1 11 Recorder of Deeds Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster (amendment) 1 46 Recorder of Deeds Adams County Girl Scout Council Inc. (Penn Laurel G. S. Council Inc.) E-51 956 Recorder of Deeds Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. 4 322 Prothonotary Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir From 1899 to 2013 this history is based on the writings of Roland Brooke and the first history contained in the original website (no longer operational). From 2013 it is the work of Dr Hugh Cutler sometime Chairman and subsequently Communications Officer and editor of the website. The Years 1899-1950 The only indication of the year of foundation is that 1899 is mentioned in an article in the Lancaster Guardian dated 13th November 1926 regarding the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. & Mrs. R.T. Grosse. In this article it states that he was 'for many years the Conductor of the Lancaster Male Voice Choir which was formed at the end of 1899'. The Guardian in February 1904 reported that 'the Lancaster Male Voice Choir, a new organisation in the Borough, are to be congratulated on the success of their first public concert'. The content of the concert was extensive with many guest artistes including a well-known soprano at that time, Madame Sadler-Fogg. In the audience were many honoured guests, including Lord Ashton, Colonel Foster, and Sir Frederick Bridge. In his speech, the latter urged the Choir to 'persevere and stick together'. Records state that the Choir were 'at their zenith' in 1906! This first public concert became an annual event, at varying venues, and their Sixth Annual Concert was held in the Ashton Hall in what was then known as 'The New Town Hall' in Lancaster. This was the first-ever concert held in 'The New Town Hall', and what would R.T. -

The First World War

OTHER PLACES OF INTEREST Lancaster & Event Highlights NOW AND THEN – LINKING PAST WITH THE PRESENT… Westfield War Memorial Village The First The son of the local architect, Thomas Mawson, was killed in April Morecambe District 1915 with the King’s Own. The Storey family who provided the land of World War Sat Jun 21 – Sat Oct 18 Mon Aug 4 Wed Sep 3 Sat Nov 8 the Westfield Estate and with much local fundraising the village was First World War Centenary War! 1914 – Lancaster and the Kings Own 1pm - 2pm Origins of the Great War All day ‘Britons at War 1914 – 1918’ 7:30pm - 10pm Lancaster and established in the 1920s and continued to be expanded providing go to War, Exhibition Lunchtime Talk by Paul G.Smith District Male Voice Choir Why remember? Where: Lancaster City Museum, Market Where: Lancaster City Museum, Where: Barton Road Community Centre, Where: The Chapel, University accommodation for soldiers and their families. The village has it’s Square, Lancaster Market Square, Lancaster Barton Road, Bowerham, Lancaster. of Cumbria, Lancaster own memorial, designed by Jennifer Delahunt, the art mistress at Tel: 01524 64637 T: 01524 64637 Tel: 01524 751504 Tel: 01524 582396 EVENTS, ACTIVITIES AND TRAIL GUIDE the Storey Institute, which shows one soldier providing a wounded In August 2014 the world will mark the one hundredth Sat Jun 28 Mon Aug 4 Sat Sep 6 Sun Nov 9 soldier with a drink, not the typical heroic memorial one usually anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. All day Meet the First World War Soldier 7pm - 9pm “Your Remembrances” Talk All day Centenary of the Church Parade of 11am Remembrance Sunday But why should we remember? Character at the City Museum Where: Meeting Room, King’s Own Royal the ‘Lancaster Pals’ of the 5th Battalion, Where: Garden of Remembrance, finds. -

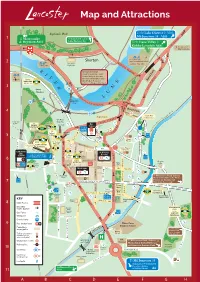

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values. -

JL-Friends-Newsletter-August-2020

1 LANCASTER JUDGES’ LODGINGS UPDATE Newsletter of the Friends of Lancaster Judges’ Lodgings Issue no 44 August 2020 The Judges’ Lodgings in August The final decision for the Judges’ Lodgings to reopen for Bank Holiday weekend was made at the beginning of the month, so although work had been going on to make the JL ready in itself, as well as covering all the Covid-secure requirements, the pace of activity quickened somewhat now that an actual date had been set. Staff had to be brought back into the JL as a team, volunteers confirmed, rotas set, new training provided, final tidy up of garden, collection cleaning – a flurry of excitement tinged with apprehension, with a new normal looming ahead so very different from the old. By opening day, Friday 28 August, all was ready (at least unready bits didn’t show), the doors were opened wide and the new glass porch was revealed on the way into the entrance hall. The porch has doors opening either to the right or the left, so was immediately the start of the one- way system round the building. Discreet Covid-secure signs were in place, guiding the flow, regulating distances and offering hand sanitisation stations. Even the display furniture was brought into use. Staff are wearing visors, visitors must wear face coverings, but none of it detracts from the charm of the JL itself. Once through reception in the main hall the way led to and through the brand new Welcome Gallery. A Charitable Incorporated Organisation Charity number 1171209 2 The Welcome Gallery This is an exciting initiative, now installed in what used to be the ticket and shop area. -

Early Stages of the Quaker

LA N CA s E N O N CON EOR M T T Y TH E EJECTED OF 1 66 2 I N C U M BER LA N D AN D WESTM ORLAN D H ISTOR Y O F I N DE P EN DENC Y I N TOC K HOLES TH E STOR Y O F TH E LANCASH I R E CON GRE GAT IONA L U N I ON TH E SER M ON ON TH E M OU NT I N R ELAT T ON T o THE P RESENT WA R CON SC I ENCE AN D THE WA R FRO M TH E GREAT AWA KE N T NG T o THE E V AN GELICAL R EV I V AL FI DELITY TO AN I DEAL CON G R EGATIONALIS M R E -E XAM IN ED I C A M BR E H E R E L l Gl O U S M Y TIC SAA OS , T S THO M AS j OLu E O F ALTH A M AN D WYM ON D HOU SES THE H ERox c A GE O F CON G RE GATIONA LISM EA R L Y ST A GE S O F T H Q UA K E R M O V E M EN T IN L A N CA SH IR E BB BB B R B M A . E . A D. V . m . NIGHTIN G LE , , CONGR EGAT I P R E FA CE A FEW years ago while engaged in s ome hist orical research or m r andPWestmorland r m w k in Cu be land , elating ainly t o 1 r m o o the 7th centu y , I ca e much int c ntact with the r mo of r o Not Quake vement that pe i d . -

The Nature of the English Corresponding Societies 1792-95

‘A curious mixture of the old and the new’? The nature of the English Corresponding Societies 1792-95. by Robin John Chatterton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Arts by Research. Department of History, College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham, May 2019. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis relates to the British Corresponding Societies in the form they took between 1792 and 1795. It draws on government papers, trial transcripts, correspondence, public statements, memoirs and contemporary biography. The aim is to revisit the historiographical debate regarding the societies’ nature, held largely between 1963 and 2000, which focused on the influence on the societies of 1780s’ gentlemanly reformism which sought to retrieve lost, constitutional rights, and the democratic ideologies of Thomas Paine and the French Revolution which sought to introduce new natural rights. The thesis takes a wider perspective than earlier historiography by considering how the societies organised and campaigned, and the nature of their personal relationships with their political influences, as well as assessing the content of their writings. -

Thomas Paine and the Walkers: an Early Episode in Anglo-American Co-Operation

THOMAS PAINE AND THE WALKERS: AN EARLY EPISODE IN ANGLO-AMERICAN CO-OPERATION By W. H. G. ARMYTAGE TN THE year 1780, Thomas Paine was awarded the honorary l degree of Master of Arts by the University of Pennsylvania for his powerful literary cannonades against the Britsh govern- ment. Two years earlier, Samuel Walker,' a Yorkshire ironmaster, had prospered so well from the sale of guns that he obtained armorial bearings, 2 and in the year in which Paine was awarded a degree he completed an unprecedented casting of no less than 872 tons of cannon, a figure which he raised by fifty per cent the following year. That a principal armaments manufacturer for the British and an even more prominent pamphleteer against them, should be working on common ground within the decade seemed incredible. Yet it was so, and the link between them was itself symbolic: an iron bridge.3 Paine's invention for an iron bridge was as American as any- thing else about him. For, on his own avowal to Sir George Staun- ton,4 the idea was conceived as he witnessed the ice packs and melting snows which would bear so hardly on any bridge built on piers across the Schuylkill at Philadelphia. Scarcely was the war 11715-1782, an orphan at 14, then a self taught village schoolmaster who joined forces with his brother Aaron (1718-1777) to manufacture shoe buckles and laundresses' irons. Joining with John and William Booth (who had discovered the Huntsman secret of making steel), they built a foundry at Masborough in 1749, and developed the mineral resources of the district with great rapidity. -

ACTS, 1787-1790 G. M. Ditchfield, B.A., Ph.D

THE CAMPAIGN IN LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE FOR THE REPEAL OF THE TEST AND CORPORATION ACTS, 1787-1790 G. M. Ditchfield, B.A., Ph.D. N due season we shall reap, if we faint not'. A sermon on this Itext was preached by a Lancashire Dissenting minister on 7 March 1790, five days after the House of Commons had rejected a motion for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts by the decisive margin of 294 votes to IO5-1 The text serves to illustrate the religious nature of the issue in question and the sense of injustice which it aroused. Both points are significant. For many historians of the period seem to agree that a new 'political con sciousness' based on discontented radicalism and on a greatly increased degree of popular participation in political activity appeared in Lancashire and Cheshire in the late 17805 and in the 17905. It is proposed here to suggest at least one reason why this should have been so and to offer a religious dimension to what has been called 'the emergence of liberalism'.2 The continued existence of the Test and Corporation Acts, with their seventeenth century heritage, remained a potential source of conflict between the established church and those outside it. The renewed efforts to secure their repeal in 1787-90, though unsuccessful, helped to concentrate dissatisfaction with the 'old regime', to facilitate the development of the radical consciousness of the early nineteenth century and to promote the clearer identification and organisation of the forces which were opposed to change. This conflict took on a particularly bitter tone in Lancashire and Cheshire.