Environmental Baseline Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

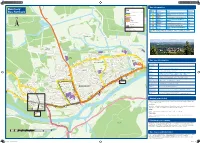

Banchory Bus Network

Bus Information A Banchory 9 80 Key Service Bus Network Bus services operating around Banchory Number Operator Route Operation 105 201 Stagecoach Aberdeen-Banchory-Aboyne-Ballater- Bluebird Braemar M-F, S, Su 201.202.203 202 Stagecoach 204 Bluebird Aberdeen-Banchory-Lumphanan/Aboyne M-F, S, Su Brathens VH5PM VH3 203 Stagecoach Aberdeen-Banchory/Aboyne/Ballater/ Wood Bluebird Braemar M-F VH5PM 204 Stagecoach Direction of travel Bluebird Aberdeen-Banchory-Strachan M-F ©P1ndar Bus stop VH3 Deeside Tarland-Aboyne-Finzean-Banchory Thu Building Drumshalloch Contains Ordnance Survey data VH5 Aboyne-Lumphanan-Tarland/Banchory © Crown copyright 2016 Deeside Circular F A980 Wood Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative www.pindarcreative.co.uk 01296 390100 Key: M-F - Monday to Friday Thu - Thursday F - Friday S - Saturday Su - Sunday Locton of Leys Upper Locton Wood VH5PM Upper Banchory Woodend Barn Locton Business Arts Centre Centre Biomass Road ’Bennie Energy Burn O Centre Business h ©P1ndar rc Tree C Centre a re L s ce t ©P1ndar n Pine Tree ry Eas H t ho Business il A Road ill of Banc l o 9 ©P1ndar H Centre f 8 B 0 ©P1ndar 201.202.203 ancho Raemoir 203 Pine Tree 201.202.203 Larch Tree Road ry Garden Centre d ©P1ndar E Crescent a a 203 o Hill of ©P1ndar s Oak Tree ©P1ndar R t y West e Banchory Avenue Hill of Banchor Larch Tree e ©P1ndar r Burn of Raemoir ©P1ndar Crescent Pine T Hill of Bus fare information Garden Sycamore ©P1ndar Bennie ©P1ndar Banchory ©P1ndar Centre Place ©P1ndar Sycamore Oak Tree Hill of Banchory Place Tesco Avenue ©P1ndar 203 est Tesco W d ry a Holly Tree ho 201.202 o VH5PM anc e R Ticket type Road f B Tre VH5PM ©P1ndar o aird’s W ll ne 201.202.203 C y i h Pi nd H t u ent VH5PM o resc Tesco S C ©P1ndar ©P1ndar stnut y he Single For a one-way journey, available on the bus. -

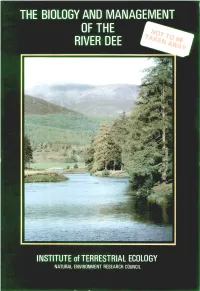

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

1 Rural Affairs and Environment Committee

RURAL AFFAIRS AND ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE WILDLIFE AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT (SCOTLAND) BILL WRITTEN SUBMISSION FROM DR ADAM WATSON Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Bill, consultation I request members of the Rural Affairs & Environment Committee to take the decisive action that is long overdue to end the widespread and increasing illegal persecution of protected Scottish raptors. Leading MSPs and Scottish Ministers in the previous Labour/Lib Dem coalition and the present SNP administration have condemned this unlawful activity, calling it a national disgrace. However, it continues unabated, involving poisoning as well as shooting and other illegal activities. Indeed, it has increased, as is evident from the marked declines in numbers and distribution of several species that are designated as in the highest national and international ranks for protection. In 1943 I began in upper Deeside to study golden eagles, which have now been monitored there for much longer than anywhere else in the world. I have also studied peregrines and other Scottish raptor species, and snowy owls in arctic Canada. This research resulted in many papers in scientific journals. An example was in 1989 when I was author of a scientific paper that reviewed data on golden eagles from 1944 to 1981. It showed the adverse effects of eagle persecution on grouse moors, in contrast to deer forests where the birds were generally protected or ignored by resident deerstalkers. Also it showed how a decline of such persecution during the Second World War, when many grouse-moor keepers were in the armed services, led to a notable increase of resident eagle pairs on grouse moors. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

Land Management Plan

Deeside Woods LMP Moray & Aberdeenshire Forest District Banchory Woods Land Management Plan Plan Reference No: LMP 35 Plan Approval Date: Plan Expiry Date: 1 | Banchory Woods LMP 2018 -2027 | M Reeve | November 2018 Banchory Woods Land Management Plan 2018 - 2027 2 | Banchory Woods LMP 2018 – 2027 | M Reeve | November 2018 Banchory Woods Land Management Plan 2018 - 2027 FOREST ENTERPRISE - Application for Forest Design Plan Approvals in Scotland Forest Enterprise - Property Forest District: Moray & Aberdeenshire FD Woodland or property name: Banchory Woods Nearest town, village or locality: Banchory OS Grid reference: NO 688 948 Areas for approval Conifer Broadleaf Clear felling 196.9ha 3.2ha Selective felling 11.5ha Restocking 117.0ha 133.0ha New planting (complete appendix 4) 1. I apply for Forest Design Plan approval*/amendment approval* for the property described above and in the enclosed Forest Design Plan. 2. * I apply for an opinion under the terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment (Forestry) (Scotland) Regulations 1999 for afforestation* /deforestation*/ roads*/ quarries* as detailed in my application. 3. I confirm that the initial scoping of the plan was carried out with FC staff on July 2015 4. I confirm that the proposals contained in this plan comply with the UK Forestry Standard. 5. I confirm that the scoping, carried out and documented in the Consultation Record attached, incorporated those stakeholders which the FC agreed must be included. 6. I confirm that consultation and scoping has been carried out with all relevant stakeholders over the content of the of the design plan. Consideration of all of the issues raised by stakeholders has been included in the process of plan preparation and the outcome recorded on the attached consultation record. -

A3autumn 2007

Page 8 Autumn 2007 The Newsletter for the Cairngorms Campaign CAIRNGORM STORIES Enhancing the Conservation of the Cairngorms A Cairngorms Day their higher and lower peaks is often great. But the Scottish hills arose differently. Ice flows of the ice ages The forecast said that Friday would be one of the few and later weathering cut out corries, ridges etc from a fine days this miserable summer. You can’t afford to high plateau. There is thus is small difference in height T HE CAIRNGORMS CAMPAIGNER miss these limited chances, can you? August still gave between peaks. So, from the highest summits, immense Cairngorms panoramas open up to distant horizons of Autumn 2007 hills upon hills. The lungs breath deep but, looking at these scenes, the heart breaths deeply too. We chat INSIDE THIS ISSUE: pleasantly with a young lone hiker. He is up from Conserving the Mountain Hare? England and heading back to his camp. That apart, only one person passes between there and the final summit Few animals on the Scottish hills and sporting estates showing hundreds shot where lunch is occupied with discussions on which far Conserving the 1 mountains are more attractive than the and hung up. It is difficult to think of any peaks we see and which should be visited next. Mountain hare? mountain hare. Rob Raynor, Policy and time in the last fifty years or more when Advice Officer with Scottish Natural such drives would have produced this Action by the Heritage, states, “The mountain hare is result. Are there other more enduring Back at Corour hut, another hiker from England is 2-3 Campaign an iconic species which is highly factors at work such as prolonged heavy camping with his girl friend (“Hullo! Fine day!”) and there specialised to deal with its grazing by sheep and deer altering - crossing the bog and over the bridge, comes a small Brief Book review 3 environment. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

The Cairngorm Club Journal 110, 2013

76 BOOK REVIEWS The Cairngorms: 100 Years of Mountaineering. Greg Strange, 2101. Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 400pp. ISBN 978-1-907233-1-1 This magisterial volume by the author of a well-used SMC climbing guide to the Cairngorms, covers the century from 1893 (the ascent of the Douglas-Gibson Gully) onwards. To this Club, founded six years earlier, that choice of starting date may seem odd, even contentious, but it signals that the focus of this book is firmly about climbing on rock and ice, even if there are occasional mentions of skiing, bothies, some environmental issues (hill tracks, the Lurcher's Gully Inquiry, but not climate change) and even walks. Given that focus, it is hard to fault the book, at least from a non/ex-climber's viewpoint: it takes the reader through each main first ascent with a happy mixture of background information on the participants, the day (and/or night) as a whole, and sufficient detail on the main pitches, including verbatim (or at least reported) conversations. Delightfully, most pages carry a photograph of the relevant route, landscape or character(s), the accumulation of which must represent a tremendous effort in contacting club and personal archives. Throughout the century the energy and endurance of the pioneers are evident, perhaps most to those who have themselves tramped the approach miles, and sampled Cairngorm weather and terrain, even if they have never attempted the technical feats here described. The 12 main chapters cover the period in a balanced way, but the pride of place must go to the central chapters on 'The Golden Years' (1950-1960) in 56 pages, 'The Ice Revolution' (1970-1972) in 38 pages and 'The Quickening Pace' (1980-1985) in 58 pages. -

ANNEX C: SITE BRIEF: South of Devil's Elbow Glenshee, A93

ANNEX C: SITE BRIEF: South of Devil’s Elbow Glenshee, A93, Cairngorms National Park Location The lay-by is located on A93 north of Spittal of Glenshee, Grid Reference NO140757 See attached Map 1. The site is within the Cairngorms National Park some 3 km south of Glenshee Ski Centre. Perth and Kinross Council is the roads authority. Ownership The land is owned by Invercauld Estate Background The A93 forms part of the Deeside Tourist Route which runs from Perth to Aberdeen via Blairgowrie, Braemar, and Ballater. This route is the main access from the south to the Glenshee Ski Area. As one of the classic Scottish ‘snow roads’ the A93 is often sought out as a test piece by cyclists, motor cyclists and classic car drivers: it is a well published option on the Lands End to John o’ Groats route. It forms the main link road between Deeside and Perthshire. This lay-by is well used by hill walkers wanting to access the four Munros west of Glenshee including Glas Maol 1068m. The current lay-by appears to have been formed as a result of realigning the road. Upgrading the lay-by has been an aspiration of the community for a number of years and it is a specific action in the Mount Blair Community Action Plan. Interpretation and Information Glenshee takes its name from the Gaelic word shith, signifying ‘fairies’. Until the old tongue died out in the late 1800’s the inhabitants were known as Sithichean a’ Ghlinnshith - ‘The Elves of Glenshee’. The road has been important for centuries as a route through the mountains. -

Piper PA-32R-300 Cherokee Lance, G-BSYC No & Type of Engines

AAIB Bulletin: 11/2009 G-BSYC EW/C2008/04/01 ACCIDENT Aircraft Type and Registration: Piper PA-32R-300 Cherokee Lance, G-BSYC No & Type of Engines: 1 lycoming IO-540-K1G5D piston engine Year of Manufacture: 1977 Date & Time (UTC): 5 April 2008 at 0948hrs Location: Cairn Gorm, Cairngorms, Scotland Type of Flight: Private Persons on Board: Crew - 1 Passengers - None Injuries: crew - 1 (Fatal) Passengers - N/A Nature of Damage: Aircraft destroyed Commander’s Licence: Private Pilot’s Licence Commander’s Age: 45 years Commander’s Flying Experience: Approximately 440 hours (of which at least 126 were on type) Last 90 days - not known Last 28 days - not known Information Source: AAIB Field Investigation Synopsis History of the flight The pilot had planned to fly the aircraft from the United The pilot had planned to fly from the UK to Orlando, Kingdom (UK) to the United States of America (USA) Florida, USA. He began the journey at Gamston Airfield, and was en route from carlisle to Wick. He was flying Nottinghamshire on Friday 4 April 2009, departing from VFR and was in receipt of a Flight Information Service there at 1025 hrs. He then flew to Wolverhampton from ATC. Heading north-north-east over the northern Halfpenny Green Airport, arriving there at 1111 hrs and part of the Cairngorms, he descended the aircraft from uplifted 177 litres of fuel. At 1123 hrs he departed for an altitude of 8,300 ft amsl to 4,000 ft amsl, whereupon Carlisle. At some point that morning he telephoned he encountered severe weather and icing conditions. -

The Cairngorms Guia

2018-19 EXPLORE The cairngorms national park Pàirc Nàiseanta a’ Mhonaidh Ruaidh visitscotland.com ENJOYA DAY OUT AND VISIT SCOTLAND’S MOST PRESTIGIOUS INDEPENDENT STORE The House of Bruar is home to in our Country Living Department the most extensive collection and extensive Present Shop. Enjoy of country clothing in Great a relaxing lunch in the glass- Britain. Our vast Menswear covered conservatory, then spend an Department and Ladieswear afternoon browsing our renowned Halls showcase the very best in contemporary rural Art Galley leather, suede, sheepskin, waxed and Fishing Tackle Department. cotton and tweed to give you Stretch your legs with a stroll up the ultimate choice in technical the Famous Bruar Falls, then and traditional country clothing, treat yourself in our impressive while our Cashmere and Knitwear Food Hall, Delicatessen and Hall (the UK’s largest) provides award-winning Butchery. a stunning selection of luxury To request our latest mail natural fibres in a vast range of order catalogue, please colours. Choose from luxurious call 01796 483 236 or homeware and inspirational gifts visit our website. The House of Bruar by Blair Atholl, Perthshire, PH18 5TW Telephone: 01796 483 236 Email: offi[email protected] www.houseofbruar.com COMPLETE YOUR VISIT NEWFANTASTIC FISH & CHIP REVIEWS SHOP welcome to the cairngorms national park 1 Contents 2 The Cairngorms National Park at a glance 4 Heart of the park 6 Wild and wonderful ENJOYA DAY OUT AND VISIT 8 Touching the past SCOTLAND’S MOST PRESTIGIOUS INDEPENDENT STORE 10 Outdoor