Accessibility and Public Transport in Sheffield: Case Studies of Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

51 Cardoness Road | Crosspool | Sheffield

Tenure Freehold Council Tax Band C Viewing Arrangements Strictly by appointment Contact Details All enquiries and negotiations are conducted via Cocker & Carr Ltd. We are 11 Sandygate Road obliged under the Estate Agency Act 1991 to qualify all offers and as such an independent mortgage consultant will speak to you to substantiate your details. 51 Cardoness Road | Crosspool | Sheffield | S10 5RT Sheffield The property particulars are for guidance only and do not constitute part of an South Yorkshire offer or contract. • No onward chain S10 5NG Whilst every attempt has been made to ensure the accuracy of the floor plan and • Three bedrooms details contained within this brochure, measurements of room sizes and any www.cockerandcarr.co.uk other items are approximate and no responsibility is taken for any error, • Two reception rooms omission or mis-statement. The plan is for illustrative purposes only and sho uld [email protected] be used as such by any prospective purchaser. The services, systems and • Rear garden 01142 687777 appliances shown have not been tested and no guarantee as to their operability or efficiency can be given. Guide Price £260,000 - £270,000 size and can be tailored to the needs of the new Ciccio's, The Sportsman Pub and Crosspool owners. To the front of the property is off street Tavern Pub. Access to Sheffield City Centre, parking and a small low maintenance garden. central hospitals and Sheffield University is simple by car and bus with the 51 bus route General information running regularly throughout the day. Local The property benefits from double glazing and schools include Lydgate Lane Infant & Junior gas central heating, the Worcester combination School and Tapton Secondary School. -

™ OPEN MEETING Lollipop Man's Final Patrol

Summer2021 The Official Newsletter of the Crosspool Forum Volume 18 Issue 2 Having a voice . Making a difference ™ CROSSPOOL NEWS - crosspool.info 3000 copies delivered quarterly Editor: Ian Hague Lollipop Man’s Final Patrol Crosspool Community Hub As the Maundy Thursday school bell rang out, all Still Here to Help the staff, parents and Despite all the focus on the pupils of Lydgate Infants extremely well organised and School in Crosspool con- effective Vaccination Pro- gregated on the school gramme at St Columba’s, we crossing to say a fond want to emphasise that we farewell to their very pop- are still available to help with ular (lollipop) crossing any needs arising from the patrolman. pandemic and its aftermath, Eddie Parton, who lives just down the road in Crookes, has which includes Shopping, or been a familiar face seeing many hundreds of children safe- help sourcing home deliveries ly across Lydgate Lane for the past 11 years come rain or Collecting Prescriptions Dog shine and never having a day off. Walking Telephone chats Eddie told the Crosspool News that, “this has been the best around isolation issues and job he has ever had and felt very privileged to have had a fears and any other situations job where he was greeted with so many happy and smiling you are struggling with faces every working day”. Eddie also went on to say, “I will miss the job and all the lovely people who have become my Thankfully, calls to us have friends, but I felt that now is the time to call it a day and let decreased significantly, and someone else take over the roll”. -

Agenda Item 3

Agenda Item 3 Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield S1 2HH, on Wednesday 5 December 2012, at 2.00 pm, pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor John Campbell) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Vickie Priestley) 1 Arbourthorne Ward 10 Dore & Totley Ward 19 Mosborough Ward Julie Dore Keith Hill David Barker John Robson Joe Otten Isobel Bowler Jack Scott Colin Ross Tony Downing 2 Beauchiefl Greenhill Ward 11 East Ecclesfield Ward 20 Nether Edge Ward Simon Clement-Jones Garry Weatherall Anders Hanson Clive Skelton Steve Wilson Nikki Bond Roy Munn Joyce Wright 3 Beighton Ward 12 Ecclesall Ward 21 Richmond Ward Chris Rosling-Josephs Roger Davison John Campbell Ian Saunders Diana Stimely Martin Lawton Penny Baker Lynn Rooney 4 Birley Ward 13 Firth Park Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Denise Fox Alan Law Sioned-Mair Richards Bryan Lodge Chris Weldon Peter Price Karen McGowan Shelia Constance Peter Rippon 5 Broomhill Ward 14 Fulwood Ward 23 Southey Ward Shaffaq Mohammed Andrew Sangar Leigh Bramall Stuart Wattam Janice Sidebottom Tony Damms Jayne Dunn Sue Alston Gill Furniss 6 Burngreave Ward 15 Gleadless Valley Ward 24 Stannington Ward Jackie Drayton Cate McDonald David Baker Ibrar Hussain Tim Rippon Vickie Priestley Talib Hussain Steve Jones Katie Condliffe 7 Central Ward 16 Graves Park Ward 25 Stockbridge & Upper Don Ward Jillian Creasy Ian Auckland Alison Brelsford Mohammad Maroof Bob McCann Philip Wood Robert Murphy Richard Crowther 8 Crookes Ward 17 Hillsborough Ward 26 Walkey Ward Sylvia Anginotti Janet Bragg Ben Curran Geoff Smith Bob Johnson Nikki Sharpe Rob Frost George Lindars-Hammond Neale Gibson 9 Darnall Ward 18 Manor Castle Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Harry Harpham Jenny Armstrong Trevor Bagshaw Mazher Iqbal Terry Fox Alf Meade Mary Lea Pat Midgley Adam Hurst 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Jackie Satur Page 5 Page 6 Council 5.12.2012 1. -

SJS Stars of the Week Farwell To... Welcoming

www.stocksbridge-jun.sheffield.sch.uk Issue No. 401 19/07/2019 SJS Stars Of The Week Y3AW: Miley McCoid Y4JJ: Mika Butcher Y5CS: Morgan Damms Y6CP: Erin Rees Y3KT: Ellie Gaymond Y4RL: Jared Horner Y5DW: Alfie Noden Y6ER: Lexi-Giselle Kimpton Y3RD: Naomi Naylor Y4SS: Inza Sajid Y5HK: Flynn Rogers Y6MC: Ryan Beal Mr Tee: Precilia Tshibangu Y3/4 Yard: Harvey Stephenson Dining-Hall: Lillie Bowskill Mrs Foster: Arley Hughes Y5/6 Yard: Emma Tompkin Farwell To... We are sure you would all join us in wishing our departing members of staff well as they move on to new appointments and thank them for their contribution to our children and families. Mrs Hetherington is off to put her expert skills to great use across Sheffield in the Learning Support Service, Mr Janiszewski has been appointed as a Year 4 teacher at a school in High Green and Miss Hudson has been appointed as a Teaching Assistant in a school in Walkley. And a final message to our Year 6 children… Welcoming... We are very pleased to officially announce that the following members of staff will be joining us in September: Mr Gamban will be joining us as a Year 4 teacher from September. Mr Gamban was an absolute asset to our Year 4 and PE teaching teams this academic year during his initial teacher training placement and we are very much looking forward to him becoming a member of our teaching team. Mr Shaw and Miss Tether will be joining us as Teaching Assistant Apprentices. This Week's Class Attendance Y3AW: 98.1% Y4JJ: 98.8% Y5CS: 95.8% Y6CP: 94.4% Y3KT: 98.5% Y4RL: 96.9% Y5DW: 99.1% Y6ER: 95.8% Y3RD: 100% Y4SS: 96.1% Y5HK: 95.7% Y6MC: 98.5% This week’s whole school attendance = 97.3% Attendance We would like to say a very well done to the 123 children who have attended school every single day during the Summer term! Certificates will be coming home today. -

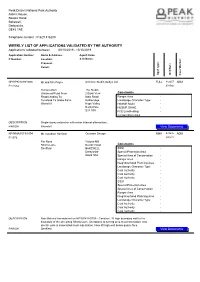

Weekly List of Applications

Peak District National Park Authority Aldern House, Baslow Road, Bakewell, Derbyshire, DE45 1AE Telephone number : 01629 816200 WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS VALIDATED BY THE AUTHORITY Applications validated between 09/10/2019 - 15/10/2019 Application Number: Name & Address: Agent Name P Number: Location: & Address: Proposal: Parish: Appl. type: Grid Ref.: Case Worker: NP/HPK/1019/1090 Mr and Mrs Payne Architect Studio Gedye Ltd FULL 412257 ADM P 11514 374566 Hunters Barn The Studio Unnamed Road From 2 Bank View Constraints Road Leading To Main Road Ranger Area - Tunstead To Glebe Farm Hathersage Landscape Character Type - Wormhill Hope Valley HBSMR MON - Derbyshire HBSMR SHINE - S32 1BB FCE Landholding - Conservation Area - DESCRIPTION Single storey extension with minor internal alternations. PARISH Wormhill View Documents NP/NMA/1019/1094 Mr Jonathan Harrison Oulsnam Design NMA 429626 ADM P 1076 380722 Far Nova Victoria Mill Shorts Lane Buxton Road Constraints Sheffield BAKEWELL SSSI - Derbyshire Special Protection Area - DE45 1DA Special Area of Conservation - Ranger Area - Neighbourhood Planning Area - Landscape Character Type - Coal Authority - Coal Authority - Coal Authority - SSSI - Special Protection Area - Special Area of Conservation - Ranger Area - Neighbourhood Planning Area - Landscape Character Type - Coal Authority - Coal Authority - Coal Authority - DESCRIPTION Non Material Amendment on NP/S/0818/0705 - Construct 4ft high boundary wall to the boundary of the site along Shorts Lane. Alterations to turning area to accommodate new electric pole & associated small sub-station. New 4ft high wall below quarry face. PARISH Sheffield View Documents WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS VALIDATED BY THE AUTHORITY Applications validated between 09/10/2019 - 15/10/2019 Application Number: Name & Address: Agent Name P Number: Location: & Address: Proposal: Parish: Appl. -

Rivelin Corn Mill North Sheffield Waw Circular Walk

This document was produced by and is copyright to the Bradfield and Stocksbridge Walkers are Welcome groups. It is distributed in association with Sheffield Lakeland Landscape Partnership Walkers are Welcome UK is a nationwide network which aims to encourage towns and villages to be ‘welcoming to walkers.’ Bradfield Walkers are Welcome https://bradfield-walkers.org.uk/ Stocksbridge Walkers are Welcome https://stocksbridge-walkers.org.uk/ Short Walk: Rivelin Corn Mill circular • Length – 2.6 miles (4.2 km) • Grade – A mixture of roads, surfaced tracks and unsurfaced paths. When walking near the river, watch out for tree roots. Most of the route is fairly level, but the terrain can be uneven and wet. There are a couple of steady climbs. In inclement weather, parts can be very muddy. • Start – Rails Road car park • Grid Reference – SK 291 872 • Parking – Rails Road car park • Public transport – the 257 bus route from Central Sheffield passes along the A57 close to the start point. • Refreshments – The Rivelin Hotel • Public Toilets – none on the route Description We commence by taking the riverside path, before ascending to views over the Rivelin Valley and returning via an ancient route, Coppice Wood, and a bridleway. The Packhorse Bridge at Rails Road (2) 1 Bradfield/Stocksbridge Walkers are Welcome Rivelin Corn Mill Circular Route Instructions The car park is the site of the Rivelin Corn Mill. This mill operated from the early 1600s, making it one of the earliest in the Valley. Rapid development of industry in the 1800s led to the mill prospering. This continued when the water supply improved with the building of dams further up the valley. -

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas Served Chapeltown Tankersley Stocksbridge Places on the Rout

Bus service(s) 201 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Chapeltown Chapeltown Station Tankersley Wentworth Business Park Stocksbridge Fox Valley Retail Park What’s changed Change of operator (Powells) following award of tender. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 201 18/10/2018 Oxspring Crane Moor Birdwell Thurgoland Pilley Green Moor Tankersley, Wentworth Way/Maple Rd Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road/ Stocksbridge, Ó Smithy Moor Lane Manchester Rd/ Tankersley, Maple Rd/ Opp Stocksbridge Library Wentworth Business Park Ò Stocksbridge, Fox Valley Way/Hunshelf Road 201 Stocksbridge, Manchester Rd/Victoria St Stocksbridge, Fox Valley Way/Manchester Rd High Green Howbrook Deepcar Chapeltown, Cart Rd/Newton Chambers Rd Chapeltown, Cart Rd/Chambers Dr Charltonbrook 201 Chapeltown, Lound Side/Chapeltown Stn database right 2018 and yright p o c own r C data © y e Wharnclie Side Grenoside v Sur e Oughtibridge c dnan r O High Bradfield ontains C 2018 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Stopping points for service 201 Chapeltown, Lound Side Station Road Cart Road Thorncliff e Road Tankersley Wentworth Way Maple Road Fox Valley Way Manchester Road Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road Manchester Road Fox Valley Way Tankersley Wentworth Way Maple -

Rotherham Sheffield

S T E A D L To Penistone AN S NE H E LA E L E F I RR F 67 N Rainborough Park N O A A C F T E L R To Barnsley and I H 61 E N G W A L A E W D Doncaster A L W N ELL E I HILL ROAD T E L S D A T E E M R N W A R Y E O 67 O G O 1 L E O A R A L D M B N U E A D N E E R O E O Y N TH L I A A C N E A Tankersley N L L W T G N A P E O F A L L A A LA E N LA AL 6 T R N H C 16 FI S 6 E R N K Swinton W KL D 1 E BER A E T King’s Wood O M O 3 D O C O A 5 A H I S 67 OA A W R Ath-Upon-Dearne Y R T T W N R S E E E RR E W M Golf Course T LANE A CA 61 D A 6 A O CR L R R B E O E D O S A N A A S A O M L B R D AN E E L GREA Tankersley Park A CH AN AN A V R B ES L S E E D D TER L LDS N S R L E R R A R Y I E R L Golf Course O N O IE O 6 F O E W O O E 61 T A A F A L A A N K R D H E S E N L G P A R HA U L L E WT F AN B HOR O I E O E Y N S Y O E A L L H A L D E D VE 6 S N H 1 I L B O H H A UE W 6 S A BR O T O E H Finkle Street OK R L C EE F T O LA AN H N F E E L I E A L E A L N H I L D E O F Westwood Y THE River Don D K A E U A6 D H B 16 X ROA ILL AR S Y MANCHES Country Park ARLE RO E TE H W MO R O L WO R A N R E RT RT R H LA N E O CO Swinton Common N W A 1 N Junction 35a D E R D R O E M O A L DR AD O 6 L N A CL AN IV A A IN AYFIELD E OOBE E A A L L H R D A D S 67 NE LANE VI L E S CT L V D T O I H A L R R A E H YW E E I O N R E Kilnhurst A W O LI B I T D L E G G LANE A H O R D F R N O 6 R A O E N I O 2 Y Harley A 9 O Hood Hill ROAD K N E D D H W O R RTH Stocksbridge L C A O O TW R N A Plantation L WE R B O N H E U Y Wentworth A H L D H L C E L W A R E G O R L N E N A -

Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Guide Price £190,000 - £200,000

Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Guide Price £190,000 - £200,000 Don't miss your opportunity to purchase this modern and spacious • THREE DOUBLE throughout three double bedroom semi-detached property situated on a BEDROOMS big corner plot in the highly sought after village of Mosborough. Offering • SEMI-DETACHED downstairs WC, conservatory, off road parking and well maintained • MODERN AND SPACIOUS garden. The property is well positioned for local amenities and road links THROUGHOUT to Sheffield City Centre and the M1 Motorway. This property is ideal for a • DOWNSTAIRS WC first time buyers or families alike! • CONSERVATORY Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Property Description Don't miss your opportunity to purchase this modern and spacious throughout three double bedroom semi- detached property situated on a big corner plot in the highly sought after village of Mosborough. Offering downstairs WC, conservatory, off road parking and well maintained garden. The property is well positioned for local amenities and road links to Sheffield City Centre and the M1 Motorway. This property is ideal for a first time buyers or families alike! HALLWAY Enter through composite door into welcoming hallway with neutral decor and wood effect laminate flooring. Ceiling light, radiator and stair rise to first floor landing. Doors to lounge, kitchen and downstairs WC. LOUNGE 15' 5" x 14' 10" (4.72m x 4.53m) A generous sized lounge with feature wall, laminate flooring and feature hole in wall currently housing a log burner and wood beam above. Ceiling light, radiator, TV point and two windows. Door to store room housing boiler. Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 KITCHEN 10' 2" x 11' 1" (3.10m x 3.39m) A modern kitchen fitted with ample high gloss wall and base units, wood effect worktops and tiled splash backs. -

Opus Distribution

OPUS DISTRIBUTION OPUS OPUS DISTRIBUTION OPUS DISTRIBUTION OPUS OPUS DISTRIBUTION WHY CHOOSE OPUS DISTRIBUTION? Opus Distribution is a social enterprise which provides unique distribution opportunities exclusively to independent traders, community groups, arts organisations, charities and local government. We distribute print to over 4,000 locations in Sheffield, North Derbyshire, Manchester, Leeds, Nottingham, Barnsley, Doncaster, Chesterfield and Rotherham. Opus Distribution firmly believes in the values of transparency, dedication and customer service. We do our best to give you the maximum amount of information about your print, from the point that we place it in the public sphere to the point that it is no longer in date and in need of recycling. We consider it an essential part of our service that for work completed in Sheffield and North Derbyshire we are able to recycle a client’s print once it goes out of date. The added benefit of this is that we can estimate how much print has been picked up by the public and in which areas it was best received. This allows you a great deal of feedback on which to base your next print distribution campaign. After completing each distribution run, we send our clients a detailed report of which locations have received their print and in what quantities. This helps you to track your print as time progresses. WHO DO WE SERVE? We work exclusively with local traders, community groups, local government, arts organisations, independent promoters and charities, creating and sustaining strong networks and shared ideologies of independent trading. Opus Distribution, like many other organisations in Britain today, is a firm believer in keeping our local economy strong enough to fulfil the needs of the community. -

CONSULTATION REPORT Overview of Comments Received and Officer Responses

Transformation and Sustainability SHEFFIELD LOCAL PLAN (formerly Sheffield Development Framework) CONSULTATION REPORT Overview of comments received and officer responses ‘City Policies and Sites and Proposals Map Consultation Draft 2010’ (June – August 2010) ‘Additional Site Allocation Options’ (January – February 2012) Development Services Sheffield City Council Howden House 1 Union Street SHEFFIELD S1 2SH March 2013 CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Consultations 2 3. Overall Results 5 4. Policy Comments 9 Economic Prosperity and Sustainable Employment 9 Serving the City Region 10 Attractive and Sustainable Neighbourhoods 10 Opportunities and Well-Being for All 13 Transport and Movement 14 Global Environment and Natural Resources 15 Green Environment 16 Character and Heritage 17 Areas that Look Good and Work Well 18 Land Uses in Policy Areas 19 5. Area Designations and Site Allocations Comments 21 Central Community Assembly Area 21 East Community Assembly Area 25 North East Community Assembly Area 30 South West Community Assembly Area 33 South Community Assembly Area 37 South East Community Assembly Area 41 Northern Community Assembly Area 46 Appendix 1a – City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft 2010, Policies 59 Appendix 1b – City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft 2010, Sites 67 Appendix 1c – City Policies and Sites Consultation Draft 2010, Proposals 71 Map Appendix 2 – Additional Site Allocation Options Consultation 2012 75 List of Tables Page Table 1 Total Number of Comments, Consultation Draft 2010 5 Table 2 Number of Comments by Chapter 6 Table 3 Number of Comments on Site Allocation by Community 6 Assembly Area Table 4 Number of Comments on Area Designations by Community 6 Assembly Area Table 5 Total Number of Comments, Additional Site Allocation Options 7 2012 1. -

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working / 43–62 Growth & Income / 63–82 Attainment & Ambition / 83–104 Health & Wellbeing / 105–115 Looking Forwards 03–16 Executive Summary 17–42 Living & Working 21 Population Growth 24 People & Places 32 Sheffield at Work 36 Working in the Sheffield City Region 43–62 Growth & Income 51 Jobs in Sheffield 56 Income Poverty in Sheffield 63–82 Attainment & Ambition 65 Early Years & Attainment 67 School Population 70 School Attainment 75 Young People & Their Ambitions 83–104 Health & Wellbeing 84 Life Expectancy 87 Health Deprivation 88 Health Inequalities 1 9 Premature Preventable Mortality 5 9 Obesity 6 9 Mental & Emotional Health 100 Fuel Poverty 105–115 Looking Forwards 106 A Growing, Cosmopolitan City 0 11 Strong and Inclusive Economic Growth 111 Fair, Cohesive & Just 113 The Environment 114 Leadership, Governance & Reform 3 – Summary ecutive Ex State of Sheffield State Executive Summary Executive 4 The State of Sheffield 2016 report provides an Previous Page overview of the city, bringing together a detailed Photography by: analysis of economic and social developments Amy Smith alongside some personal reflections from members Sheffield City College of Sheffield Executive Board to tell the story of Sheffield in 2016. Given that this is the fifth State of Sheffield report it takes a look back over the past five years to identify key trends and developments, and in the final section it begins to explore some of the critical issues potentially impacting the city over the next five years. As explored in the previous reports, Sheffield differs from many major cities such as Manchester or Birmingham, in that it is not part of a larger conurbation or metropolitan area.