Not for Citation Without Persmission of Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 January 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Harding, J. (2015) 'European Avant-Garde coteries and the Modernist Magazine.', Modernism/modernity., 22 (4). pp. 811-820. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2015 by Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modernism/modernity 22:4 (2015), 811-820. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine Jason Harding Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2015, pp. 811-820 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605720 Access provided by Durham University (24 Jan 2017 12:36 GMT) Review Essay European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine By Jason Harding, Durham University MODERNISM / modernity The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist VOLUME TWENTY TWO, Magazines: Volume III, Europe 1880–1940. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Download File

Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anita Tárnai All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai From 1914 to 1940 Russia lived through a series of traumatic events: World War I, the Bolshevik revolution, the Civil War, famine, and the Bolshevik and subsequently Stalinist terror. These events precipitated and facilitated a complete breakdown of the status quo associated with the tsarist regime and led to the emergence and eventual pervasive presence of a culture of violence propagated by the Bolshevik regime. This dissertation explores how the ongoing exposure to trauma impaired ordinary perception and everyday language use, which, in turn, informed literary language use in the writings of Viktor Shklovsky, the prominent Formalist theoretician, and of the avant-garde writer, Daniil Kharms. While trauma studies usually focus on the reconstructive and redeeming features of trauma narratives, I invite readers to explore the structural features of literary language and how these features parallel mechanisms of cognitive processing, established by medical research, that take place in the mind affected by traumatic encounters. Central to my analysis are Shklovsky’s memoir A Sentimental Journey and his early articles on the theory of prose “Art as Device” and “The Relationship between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style” and Daniil Karms’s theoretical writings on the concepts of “nothingness,” “circle,” and “zero,” and his prose work written in the 1930s. -

The T Ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism Gerald J Ara,Tek

The T ransrational Poetry of Russian Futurism E Gerald J ara,tek ' 1996 SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSilY PRESS Calexico Mexicali Tijuana San Diego Copyright © 1996 by San Diego State University Press First published in 1996 by San Diego State University Press, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California 92182-8141 http:/fwww-rohan.sdsu.edu/ dept/ press/ All rights reserved. -', Except for brief passages quoted in a review, no part of thisb ook m b ay e reproduced in an form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography r y , o any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, withoutthe written permission of thecop yright owners. Set in Book Antiqua Design by Harry Polkinhorn, Bill Nericcio and Lorenzo Antonio Nericcio ISBN 1-879691-41-8 Thanks to Christine Taylor for editorial production assistance 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Acknowledgements Research for this book was supported in large part by grants in 1983, 1986, and 1989 from the International Research & Ex changes Board (IREX), with funds provided by the National En dowment for the Humanities, the United States Information Agency, and the US Department of State, which administers the Russian, Eurasian, and East European Research Program (Title VIII). In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the fol lowing institutions and their staffs for aid essential in complet ing this project: the Fulbright-Bayes Senior Scholar Research Program for further support for the trips in 1983 and 1989, the American Council of Learned Societies for further support for the trip in 1986, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Brit ish Library; iri Moscow: to the Russian State Library, the Rus sian State Archive of Literature and Art, the Gorky Institute of World Literature, the State Literary Museum, and the Mayakovsky Museum; in St. -

Rayonists and Futurists: a Manifesto, 1913

MIKHAIL LARIONOV AND NATALYA GONCHAROVA Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 For biographies see pp. 79 and 54. The text of this piece, "Luchisty i budushchniki. Manifest," appeared in the miscel- lany Oslinyi kkvost i mishen [Donkey's Tail and Target] (Moscow, July iQn), pp. 9-48 [bibl. R319; it is reprinted in bibl. R14, pp. 175-78. It has been translated into French in bibl. 132, pp. 29-32, and in part, into English in bibl. 45, pp. 124-26]. The declarations are similar to those advanced in the catalogue of the '^Target'.' exhibition held in Moscow in March IQIT fbibl. R315], and the concluding para- graphs are virtually the same as those of Larionov's "Rayonist Painting.'1 Although the theory of rayonist painting was known already, the "Target" acted as tReTormaL demonstration of its practical "acKieveffllBnty' Becau'S^r^ffie^anous allusions to the Knave of Diamonds. "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," and David Burliuk, this manifesto acts as a polemical гейроп^ ^Х^ШШУ's rivals^ The use of the Russian neologism ШШ^сТиШ?, and not the European borrowing futuristy, betrays Larionov's current rejection of the West and his orientation toward Russian and East- ern cultural traditions. In addition to Larionov and Goncharova, the signers of the manifesto were Timofei Bogomazov (a sergeant-major and amateur painter whom Larionov had befriended during his military service—no relative of the artist Alek- sandr Bogomazov) and the artists Morits Fabri, Ivan Larionov (brother of Mikhail), Mikhail Le-Dantiyu, Vyacheslav Levkievsky, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romano- vich, Aleksandr Shevchenko, and Kirill Zdanevich (brother of Ilya). -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

Cubo-Futurism

Notes Cubo-Futurism Slap in theFace of Public Taste 1 . These two paragraphs are a caustic attack on the Symbolist movement in general, a frequent target of the Futurists, and on two of its representatives in particular: Konstantin Bal'mont (1867-1943), a poetwho enjoyed enormouspopu larityin Russia during thefirst decade of this century, was subsequentlyforgo tten, and died as an emigrein Paris;Valerii Briusov(18 73-1924), poetand scholar,leader of the Symbolist movement, editor of the Salles and literary editor of Russum Thought, who after the Revolution joined the Communist party and worked at Narkompros. 2. Leonid Andreev (1871-1919), a writer of short stories and a playwright, started in a realistic vein following Chekhov and Gorkii; later he displayed an interest in metaphysicsand a leaning toward Symbolism. He is at his bestin a few stories written in a realistic manner; his Symbolist works are pretentious and unconvincing. The use of the plural here implies that, in the Futurists' eyes, Andreev is just one of the numerousepigones. 3. Several disparate poets and prose writers are randomly assembled here, which stresses the radical positionof the signatories ofthis manifesto, who reject indiscriminately aU the literaturewritt en before them. The useof the plural, as in the previous paragraphs, is demeaning. Maksim Gorkii (pseud. of Aleksei Pesh kov, 1�1936), Aleksandr Kuprin (1870-1938), and Ivan Bunin (1870-1953) are writers of realist orientation, although there are substantial differences in their philosophical outlook, realistic style, and literary value. Bunin was the first Rus sianwriter to wina NobelPrize, in 1933.AJeksandr Biok (1880-1921)is possiblythe best, and certainlythe most popular, Symbolist poet. -

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience We . are satisfied if in our book the lyric and epic Futurist books were unconventionally small, and whether Margit Rowell evolution of our times is given shape. —El Lissitzky1 or not they were made by hand, they deliberately empha- sized a handmade quality. The pages are unevenly cut One of the revelations of this exhibition and its catalogue and assembled. The typed, rubber- or potato-stamped is that the art of the avant-garde book in Russia, in the printing or else the hectographic, or carbon-copied, early decades of this century, was unlike that found any- manuscript letters and ciphers are crude and topsy-turvy where else in the world. Another observation, no less sur- on the page. The figurative illustrations, usually litho- prising, is that the book as it was conceived and pro- graphed in black and white, sometimes hand-colored, duced in the period 1910–19 (in essentially what is show the folk primitivism (in both image and technique) known as the Futurist period) is radically different from of the early lubok, or popular woodblock print, as well as its conception and production in the 1920s, during the other archaic sources,3 and are integrated into and inte- decade of Soviet Constructivism. These books represent gral to, as opposed to separate from, the pages of poetic two political and cultural moments as distinct from one verse. The cheap paper (sometimes wallpaper), collaged another as any in the history of modern Europe. The covers, and stapled spines reinforce the sense of a hand- turning point is of course the years immediately follow- crafted book. -

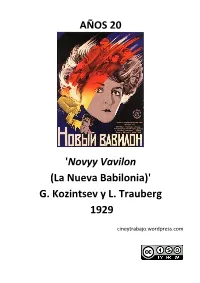

Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G

AÑOS 20 'Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G. Kozintsev y L. Trauberg 1929 cineytrabajo.wordpress.com Título original: Новый Вавилон/Novyy Vavilon; URSS, 1929; Productora: Sovkino; Director: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg. Fotografía: Andrei Moskvin (Blanco y negro); Guión: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg; Reparto: David Gutman, Yelena Kuzmina, Andrei Kostrichkin, Sofiya Magarill, A. Arnold, Sergei Gerasimov, Yevgeni Chervyakov, Pyotr Sobolevsky, Yanina Zhejmo, Oleg Zhakov, Vsevolod Pudovkin; Duración: 120′ “*...+¡La Comuna, exclaman, pretende abolir la propiedad, base de toda civilización! Sí, caballeros, la Comuna pretendía abolir esa propiedad de clase que convierte el trabajo de muchos en la riqueza de unos pocos. La Comuna aspiraba a la expropiación de los expropiadores.*...+” ¹ (Karl Marx) Sinopsis Ambientada en el París de 1870-1871, ‘La nueva Babilonia’ nos cuenta la historia de la instauración de la Comuna de París por parte de un grupo de hombres y mujeres que no quieren aceptar la capitulación del Gobierno de París ante Prusia en el marco de la guerra franco-prusiana. Louise, dependienta de los almacenes “La nueva Babilonia”, va a ser una de las más apasionadas defensoras de la Comuna hasta su derrocamiento en mayo de 1871. Comentario En 1929, Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg, dos de los creadores y difusores de la Fábrica del Actor Excéntrico (FEKS), escribieron y dirigieron la que se considera su obra conjunta de madurez: ‘Novyy Vavilon (La nueva Babilonia)’. Como muchas otras obras soviéticas se sirven de un hecho histórico real para exaltar la Revolución, pero la peculiaridad de la película de Trauberg y Kozintsev reside en que no sólo se remontan muchos años atrás en el tiempo, sino que además cambian de ubicación, situando la acción en la época de la guerra franco-prusiana de 1870 y la instauración de la Comuna de París al año siguiente. -

Chance Operations and Randomizers in Avant-Garde and Electronic Poetry Tying Media to Language

Chance Operations and Randomizers in Avant-garde and Electronic Poetry Tying Media to Language Jonathan Baillehache Abstract This article explores and compares the use of chance procedures and randomizers in Dada, Surrealism, Russian Futurism, and contemporary electronic poetry. I analyze the role of materiality of media in creating unexpected literary outcomes through a discussion of Freud’s concept of the uncanny and Katherine Hayles’s concept of computation as symptom. The goal of this essay is to compare the literary use of chance operations by historical avant-garde poets (Dadaists, Russian Futurists, and Surrealists) with the use of randomness in electronic lit- erature (specifically in generative poetry). In this essay, randomness and chance are essentially equivalent terms, but reflect different cultural and epistemological contexts. Chance is traditionally associated with art and print literature, such as automatic writing or the cut-up technique, whereas randomness in this essay is associated with computers and electronic litera- ture. Literary uses of chance or randomness are context-bound and reflect different artistic agendas: in the surrealists’ literary technique of automatic writing,1 for instance, randomness is used in order to explore the uncon- scious, whereas in Nanette Wylde’s electronic poem Storyland, randomness is used to explore the ambiguity between human subjects and machines. How do these different contexts of bibliographic publication and protocols . 1 André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s Les Champs Magnétiques, published in France in 1920, is considered one of the first books written with the method of “automatic writing”, or, as Breton puts it, “to blacken paper with a laudable disregard for any literary output” [“noircir du papier avec un louable mépris de ce qui pourrait en sortir littérairement” ]. -

1. Coversheet Thesis

Eleanor Rees The Kino-Khudozhnik and the Material Environment in Early Russian and Soviet Fiction Cinema, c. 1907-1930. January 2020 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London Supervisors: Dr. Rachel Morley and Dr. Philip Cavendish !1 I, Eleanor Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Word Count: 94,990 (including footnotes and references, but excluding contents, abstract, impact statement, acknowledgements, filmography and bibliography). ELEANOR REES 2 Contents Abstract 5 Impact Statement 6 Acknowledgments 8 Note on Transliteration and Translation 10 List of Illustrations 11 Introduction 17 I. Aims II. Literature Review III. Approach and Scope IV. Thesis Structure Chapter One: Early Russian and Soviet Kino-khudozhniki: 35 Professional Backgrounds and Working Practices I. The Artistic Training and Pre-cinema Affiliations of Kino-khudozhniki II. Kino-khudozhniki and the Russian and Soviet Studio System III. Collaborative Relationships IV. Roles and Responsibilities Chapter Two: The Rural Environment 74 I. Authenticity, the Russian Landscape and the Search for a Native Cinema II. Ethnographic and Psychological Realism III. Transforming the Rural Environment: The Enchantment of Infrastructure and Technology in Early-Soviet Fiction Films IV. Conclusion Chapter Three: The Domestic Interior 114 I. The House as Entrapment: The Domestic Interiors of Boris Mikhin and Evgenii Bauer II. The House as Ornament: Excess and Visual Expressivity III. The House as Shelter: Representations of Material and Psychological Comfort in 1920s Soviet Cinema IV.