Barra and Its History: Through the Eyes and Ears of a Modern Seanachaidh 1 Calum Macneil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anke-Beate Stahl

Anke-Beate Stahl Norse in the Place-nam.es of Barra The Barra group lies off the west coast of Scotland and forms the southernmost extremity of the Outer Hebrides. The islands between Barra Head and the Sound of Barra, hereafter referred to as the Barra group, cover an area approximately 32 km in length and 23 km in width. In addition to Barra and Vatersay, nowadays the only inhabited islands of the group, there stretches to the south a further seven islands, the largest of which are Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Bemeray. A number of islands of differing sizes are scattered to the north-east of Barra, and the number of skerries and rocks varies with the tidal level. Barra's physical appearance is dominated by a chain of hills which cuts through the island from north-east to south-west, with the peaks of Heaval, Hartaval and An Sgala Mor all rising above 330 m. These mountains separate the rocky and indented east coast from the machair plains of the west. The chain of hills is continued in the islands south of Barra. Due to strong winter and spring gales the shore is subject to marine erosion, resulting in a ragged coastline with narrow inlets, caves and natural arches. Archaeological finds suggest that farming was established on Barra by 3000 BC, but as there is no linguistic evidence of a pre-Norse place names stratum the Norse immigration during the ninth century provides the earliest onomastic evidence. The Celtic cross-slab of Kilbar with its Norse ornaments and inscription is the first traceable source of any language spoken on Barra: IEptir porgerdu Steinars dottur es kross sja reistr', IAfter Porgero, Steinar's daughter, is this cross erected'(Close Brooks and Stevenson 1982:43). -

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

Standard Committee Report

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE: 13 JUNE 2007 HEBRIDES ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION PROGRAMME Report by Director for Sustainable Communities PURPOSE OF REPORT: To report progress on implementation of the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial or other constraints to the recommendation being implemented. SUMMARY 2.1 The Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme (HAIP) was initiated to address the need for improved interpretation of archaeological sites in the Western Isles, funded jointly by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and the European Union through the Highlands and Islands Special Transitional Programme. The principal outputs comprise a series of guidebooks, development of websites, and installation of interpretative panels and access improvements at key sites throughout the islands. 2.2 A project officer was appointed, and delivery of the Programme’s objectives, now underway, is due for completion in 2008. Progress towards the stated objectives and targets is monitored by a Steering Group. This report provides a summary of progress. RECOMMENDATION 3.1 It is recommended that the Comhairle note the contents of the progress report on the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme. Contact Officer: Carol Knott, Archaeological Interpretation Officer (tel. 01851 860679) Background Papers: None REPORT DETAILS BACKGROUND 4.1 Implementation of the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme began in September 2005. The three principal objectives were progressed concurrently: • Production of a series of three guidebooks to the archaeological sites of the Western Isles, covering Barra; the Uists and Benbecula; and Lewis and Harris. • Development of websites: ‘Archaeology Hebrides’, linked to the ‘Visit Hebrides’ website, aimed at promoting the Western Isles archaeological heritage to prospective visitors; and on-line access to the Western Isles Sites and Monuments Record, a definitive database. -

Roads Revenue Programme 2008/2009 Purpose Of

DMR13108 TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE 16 APRIL 2008 ROADS REVENUE PROGRAMME 2008/2009 PURPOSE OF Report by Director of Technical Services REPORT To propose the Roads Revenue Programme for 2008/2009 for Members’ consideration. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial or other constraints to the recommendations being implemented. 1.2 Financial provision is contained within the Comhairle’s Roads Revenue Estimates for the 2008/2009 financial year which allow for the expenditure detailed in this report. SUMMARY 2.1 Members are aware of the continuing maintenance programme undertaken to the roads network throughout the Comhairle’s area on an annual basis with these maintenance works including such items as resurfacing, surface dressing, and general repairs etc. 2.2 The Marshall Block shown in Appendix 1 summarises the proposed revenue expenditure under the various heads for the 2008/2009 financial year and the detailed programme is given in Appendix 2. 2.3 Members are asked to note that because of the unforeseen remedial works that may arise, minor changes may have to be carried out to the programme at departmental level throughout the course of the financial year. 2.4 As Members will be aware the road network has in the last twelve months deteriorated at a greater rate than usual. This is mainly due to the aging bitumen in the surface together with the high number of wet days in the last few months. As a result it is proposed that a proportion of the road surfacing budget be used for “Cut Out Patching.” Due to the rising cost of bitumen products and the stagnant nature of the budget it is not felt appropriate to look at longer sections of surfacing until the damage of the last twelve months has been repaired. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Outer Hebrides (2013)

Clyde Cruising Club Amendments to Sailing Directions © Clyde Cruising Club Publications Ltd. Outer Hebrides (2013) This PDF file contains all the amendments for the above volume of the CCC Sailing Directions issued since the edition date shown. They are grouped by the date of issue and listed by page number. Plans are included only where major changes have been made or when certain amendments are difficult to describe. Users should be aware that the amendments to this website are not made with the same frequency as those issued by official hydrographic and navigational sources . Accordingly it remains necessary for those who use the CCC Sailing Directions as an aid to navigation to consult the most recent editions of Admiralty charts, all relevant Notices to Mariners issued by the UKHO, NLB, Port Authorities and others in order to obtain the latest information. Caution Whilst the Publishers and Author have used reasonable endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the contents of the Sailing Directions, and these amendments to them, they contain selected information and thus are not definitive and do not include all known information for each and every location described, nor for all conditions of weather and tide. They are written for yachts of moderate draft and should not be used by larger craft. They should be used only as an aid to navigation in conjunction with official charts, pilots, hydrographic data and all other information, published or unpublished, available to the navigator. Skippers should not place reliance on the Sailing Directions in preference to exercising their own judgement. To the extent permitted by law, the Publishers and Author do not accept liability for any loss and/or damage howsoever caused that may arise from reliance on the Sailing Directions nor for any error, omission or failure to update the information that they contain. -

Hebrides Explorer

UNDISCOVERED HEBRIDES NORTHBOUND EXPLORER Self Drive and Cycling Tours Highlights Stroll the charming streets of Stornoway. Walk the Bird of Prey trail at Loch Seaforth. Spot Otters & Golden eagles. Visit the incredible Callanish standing stones. Explore Sea Caves at Garry Beach. See the white sands of Knockintorran beach Visit the Neolithic chambered cairn at Barpa Langais. Explore the iconic Kisimul Castle. View Barra Seals at Seal Bay. Walk amongst Wildflowers and orchids on the Vatersay Machair. Buy a genuine Harris Tweed and try a dapple of pure Hebridean whiskey. Explore Harris’s stunning hidden beaches and spot rare water birds. Walk through the hauntingly beautiful Scarista graveyard with spectacular views. This self-guided tour of the spectacular Outer Hebrides from the South to the North is offered as a self-drive car touring itinerary or Cycling holiday. At the extreme edge of Europe these islands are teeming with wildlife and idyllic beauty. Hebridean hospitality is renowned, and the people are welcoming and warm. Golden eagles, ancient Soay sheep, Otters and Seals all call the Hebrides home. Walk along some of the most alluring beaches in Britain ringed by crystal clear turquoise waters and gleaming white sands. Take a journey to the abandoned archipelago of St Kilda, now a world heritage site and a wildlife sanctuary and walk amongst its haunting ruins. With a flourishing arts and music scene, and a stunning mix of ancient neolithic ruins and grand castles, guests cannot fail to be enchanted by their visit. From South to North - this self-drive / cycling Holiday starts on Mondays, Thursdays or Saturdays from early May until late September. -

Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland

Wessex Archaeology Allasdale Dunes, Barra Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 65305 October 2008 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 65305.01 October 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology and Ownership ......................1 1.3 Archaeological Background......................................................................2 Neolithic.......................................................................................................2 Bronze Age ...................................................................................................2 Iron Age........................................................................................................4 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work at Allasdale ............................................5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................6 -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Aerial Survey of Northern Gannet (Morus Bassanus) Colonies Off NW Scotland 2013

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 696 Aerial survey of northern gannet (Morus bassanus) colonies off NW Scotland 2013 COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 696 Aerial survey of northern gannet (Morus bassanus) colonies off NW Scotland 2013 For further information on this report please contact: Andy Douse Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House INVERNESS IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725000 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Wanless, S., Murray, S. & Harris, M.P. 2015. Aerial survey of northern gannet (Morus bassanus) colonies off NW Scotland 2013. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 696. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2015. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Aerial survey of northern gannet (Morus bassanus) colonies off NW Scotland 2013 Commissioned Report No. 696 Project No: 14641 Contractor: Centre for Ecology and Hydrology Year of publication: 2015 Keywords Northern gannet; Sula Sgeir; St Kilda; Flannan Islands; Sule Stack: Sule Skerry; gugas; population trends. Background Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) commissioned an aerial survey of selected colonies of northern gannets (Morus bassanus) off the NW coast of Scotland in 2013. The principal aim was to assess the status of the population in this region, which holds some important, but infrequently counted colonies (St Kilda, Sula Sgeir, Sule Stack, Flannan Islands and Sule Skerry). In addition, an up-to-date assessment was required to review the basis for the licensed taking of young gannets (gugas) from the island of Sula Main findings Aerial surveys of all five colonies were successfully carried out on 18 and 19 June 2013. -

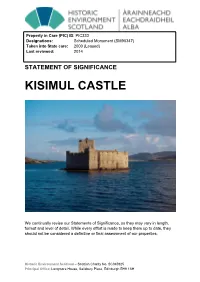

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders.