Observation and Image-Making in Gothic Art � JEAN A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAILING CONTENTS PAGE.Pub

Clergy Mailing - September 2015 Contents 1. Nifty Notes 2. Big E Day information & workshop choices 3. Big E Day booking form 4. Diocesan Conference booking form 5. Ministry Vacancies Niftynotes news & information from the Diocese www.southwell.anglican.org SEPTEMBER 2015 Compiled by Nicola Mellors email: [email protected] A voice for the voiceless Leverhulme Research Fellow and a Human ARights Activist are the keynote speakers at this year’s Racial Justice Weekend, which aims to help give a voice to the voiceless. The event is held on Saturday 12th September (10am–3.30pm) at St Stephen’s and St Paul’s Church, Hyson Green and Sunday13th September from 6pm Dr Roda Madziva at the Calvary Family Church, publics are imagined, constituted, Nottingham. engaged and mediated in immigration politics. Roda’s topic Sonia Aslam On Saturday, ‘Voice of the will cover Christians from ‘Lack of Rights of Christian Voiceless’ features keynote Muslim majority countries, their Women in Pakistan’ led by Sonia speaker, Dr Roda Madziva, who arrival in the UK as asylum Aslam; ‘Issues Providing the is a Leverhulme Research Fellow seekers and the possible double Burden of Proof – in UK re: in the School of Politics and discrimination re: Islamaphobia Blasphemy Charges’ International Relations. She holds and the burden of proof at the Continued on page 12 an MA (Social Policy and Home Office. Roda’s research Administration, Distinction) and forms part of the Leverhulme In this month’s issue: PhD (Sociology and Social funded and University of Policy) from the University of Nottingham-led programme on 2 News in brief Nottingham. -

REACHING out a Celebration of the Work of the Choir Schools’ Association

REACHING OUT A celebration of the work of the Choir Schools’ Association The Choir Schools’ Association represents 46 schools attached to cathedrals, churches and college chapels educating some 25,000 children. A further 13 cathedral foundations, who draw their choristers from local schools, hold associate membership. In total CSA members look after nearly 1700 boy and girl choristers. Some schools cater for children up to 13. Others are junior schools attached to senior schools through to 18. Many are Church of England but the Roman Catholic, Scottish and Welsh churches are all represented. Most choir schools are independent but five of the country’s finest maintained schools are CSA members. Being a chorister is a huge commitment for children and parents alike. In exchange for their singing they receive an excellent musical training and first-class academic and all-round education. They acquire self- discipline and a passion for music which stay with them for the rest of their lives. CONTENTS Introduction by Katharine, Duchess of Kent ..................................................................... 1 Opportunity for All ................................................................................................................. 2 The Scholarship Scheme ....................................................................................................... 4 CSA’s Chorister Fund ............................................................................................................. 6 Finding Choristers ................................................................................................................. -

Burchard of Mount Sion and the Holy Land

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 4 Issue 1 5-41 2013 Burchard of Mount Sion and the Holy Land Ingrid Baumgärtner Universität Kassel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Baumgärtner, Ingrid. "Burchard of Mount Sion and the Holy Land." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 4, 1 (2013): 5-41. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol4/iss1/2 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baumgärtner ___________________________________________________________________________ Burchard of Mount Sion and the Holy Land By Ingrid Baumgärtner, Universität Kassel The Holy Land has always played an important role in the imagination of the Latin Christian Middle Ages. As a multi-functional contact zone between Europe and Asia, it served as a region of diverse interactions between the three Abrahamic religions, was a destination for pilgrims, and a place where many disputes over territory took place. The armed crusades of 1099 by the Latin Christians led to the formation of the crusader states, which fell again after the final loss of Jerusalem in 1244 and the fall of Acre in 1291 to the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil. Seizures and loss of territory resulted in the production of hundreds of travel and crusade accounts, as well as some of the first 1 regional maps created in Europe for precisely this part of the world. -

Dear Friends

Little St. Mary's, Cambridge NEWSLETTER October 2010, No. 424 Price: 25p Preachers on Sundays during October 3rd: 18th after Trinity: Harvest Thanksgiving 10.30am: The Vicar 6pm Fr Mark Bishop 10th: 19th after Trinity: 10.30am: Canon Frances Ward , Dean Elect of St Edmundsbury Cathedral 6pm: The Vicar 17th: 20th after Trinity: 10.30am: David Edgerton (Ridley Hall) 6pm: The Vicar 24th: 21st after Trinity: 10.30am: Canon Alan Cole 6pm: The Vicar Special Events Saturday 9th: Society of Mary to Ely Cathedral Walsingham Cell Saturday 16th: Outing to Southwell Minster and St Mary©s Nottingham Monday 18th: Feast of St Luke: Low Mass 7.45am Sung Mass 7pm Collections for the Homes of St Barnabas Saturday 23rd: Sponsored Walk to Ely (for the Parish Centre Development Fund) CONTENTS Vicar's Letter 2-4 Harvest and Jimmy©s 9 People for our Prayers 4 Parish Centre Fund Events 10 Calendar & Intentions 5-8 Whom to Contact 11 Services at LSM 12 1 Dear Friends, On August 31st we heard at last the name of the man who is to be the next Bishop of Ely. The Rt Revd Stephen Conway is the Area, or Suffragan, Bishop of Ramsbury, in the Diocese of Salisbury, which he is currently ‘minding’ as there is also an ‘episcopal interregnum’ in that diocese. Bishop Stephen was trained at Westcott House here in Cambridge, and until he became Bishop of Ramsbury in 2006 served all his ministry in the Diocese of Durham, in two curacies, then as a Parish Priest, as Director of Ordinands and Bishop’s Chaplain, and finally as an Archdeacon. -

Centenary Celebration Report

Celebrating 100 years CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2018 Front cover photograph: Choristers representing CSA’s three founding member schools, with lay clerks and girl choristers from Salisbury Cathedral, join together to celebrate a Centenary Evensong in St Paul’s Cathedral 2018 CONFERENCE REPORT ........................................................................ s the Choir Schools’ Association (CSA) prepares to enter its second century, A it would be difficult to imagine a better location for its annual conference than New Change, London EC4, where most of this year’s sessions took place in the light-filled 21st-century surroundings of the K&L Gates law firm’s new conference rooms, with their stunning views of St Paul’s Cathedral and its Choir School over the road. One hundred years ago, the then headmaster of St Paul’s Cathedral Choir School, Reverend R H Couchman, joined his colleagues from King’s College School, Cambridge and Westminster Abbey Choir School to consider the sustainability of choir schools in the light of rigorous inspections of independent schools and regulations governing the employment of children being introduced under the terms of the Fisher Education Act. Although cathedral choristers were quickly exempted from the new employment legislation, the meeting led to the formation of the CSA, and Couchman was its honorary secretary until his retirement in 1937. He, more than anyone, ensured that it developed strongly, wrote Alan Mould, former headmaster of St John’s College School, Cambridge, in The English -

The-History-Of-The-Minster-School PDF File Download

The History of the Minster School I. Introduction The present Southwell Minster School came into being in September 1976 as an 11-18, co- educational comprehensive. One of its "ancestors" was a grammar school, established in the Middle Ages. No precise date can be given to the grammar school's foundation. It was always a small school - on a number of occasions in danger of ceasing to exist. It did not develop a reputation for producing pupils who became household names, nor did it set any trends in education. Yet, through descent from the Grammar School, the Minster School is part of a line of development which may go back further than that represented by any other English school now outside the private sector. And, precisely because the Grammar School, and the other ancestors of the modern comprehensive, were not too much out of the ordinary, their story is the more important. II. The Grammar School 1. The Origins of the Grammar School The earliest schools were linked to a monastery, cathedral or other large church, such as the Minster at Southwell. Such "grammar" schools were at first very small - made up of perhaps less than twenty boys. Pupils probably started to attend between the ages of nine and twelve. Southwell's grammar school may have been created at the same time as its Minster - to provide education for Minster choristers. The Minster is thought to have been founded soon after the Saxon King Edwy gave lands in Southwell to Oscetel, Archbishop of York, in a charter dating from between 955 and 959. -

660268-69 Bk Strauss EU

MENDELSSOHN Choral Music Sechs Sprüche • Hear my prayer • Motets, Op. 39 Magnificat and Nunc dimittis • Ave Maria • Psalm 43 Peter Holder, Organ • St Albans Abbey Girls Choir Lay Clerks of St Albans Cathedral Choir • Tom Winpenny Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) MENDELSSOHN Choral Music (1809-1847) Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1809 into a marred by ill health, the result of over-work: distressed by Choral Music distinguished Jewish family. The grandson of philosopher the death of his sister Fanny a few months earlier, he died Moses Mendelssohn and the son of a banker, he was in November 1847. Sechs Sprüche, Op. 79 10:06 recognised as a prodigious pianist at a young age. The The significant output of smaller sacred choral works 1 I. Frohlocket, ihr Völker auf Erden 1:27 family moved to Berlin in 1811, later adopting the name is set against Mendelssohn’s towering achievements – 2 II. Herr Gott, du bist uns’re Zuflucht für und für 2:29 Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and being baptised into the the oratorios St Paul (1836) and Elijah (1846). The 3 III. Erhaben, o Herr, über alles Lob 1:34 Lutheran Church. influence of Palestrina prevails in the smaller works, 4 IV. Herr, gedenke nicht unser Übeltaten 1:21 Mendelssohn began composing around 1819 under inspired by Mendelssohn’s participation in the Berlin 5 V. Lasset uns frohlocken 1:35 the tutelage of Carl Friedrich Zelter, director of the Berlin Singakademie, and by his experience attending the Holy 6 VI. Um uns’rer Sünden willen 1:38 Singakademie. Zelter was a flagbearer for the Bach Week services in the Sistine Chapel in 1831. -

Medieval Portolan Charts As Documents of Shared Cultural Spaces

SONJA BRENTJES Medieval Portolan Charts as Documents of Shared Cultural Spaces The appearance of knowledge in one culture that was created in another culture is often understood conceptually as »transfer« or »transmission« of knowledge between those two cultures. In the field of history of science in Islamic societies, research prac- tice has focused almost exclusively on the study of texts or instruments and their trans- lations. Very few other aspects of a successful integration of knowledge have been studied as parts of transfer or transmission, among them processes such as patronage and local cooperation1. Moreover, the concept of transfer or transmission itself has primarily been understood as generating complete texts or instruments that were more or less faithfully expressed in the new host language in the same way as in the origi- nal2. The manifold reasons (beyond philological issues) for transforming knowledge of a foreign culture into something different have not usually been considered, although such an approach would enrich the conceptualization of the cross-cultural mobility of knowledge. In this paper, I will examine the cross-cultural presence of knowledge in a different manner, studying works of a specific group of people who created, copied, and modified culturally mixed objects of knowledge. My focus will be on Italian and Catalan charts and atlases of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, partly because the earliest of them are the oldest extant specimens of the genre and partly because they seem to be the richest, most diverse charts of all those extant from the Mediterranean region3. In addition, I have relied on the twelfth- century »Liber de existencia riveriarum et forma maris nostris Mediterranei«, a Latin 1 Charles BURNETT, Literal Translation and Intelligent Adaptation amongst the Arabic–Latin Translators of the First Half of the Twelfth Century, in: Biancamaria SCARCIA AMORETTI (ed.), La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel Medio Evo Europeo, Rome 1987, p. -

B R I D L I N G T O N P R I O R Y O R G a N R E C I T a L S 2 0

April 27th Paul Hale May 25th John Scott Whitely June 29th Peter King July 27th Gordon Stewart Aug. 31st Daniel Cook Sept. 28th Ian Tracey Southwell Minster York Minster Bath Abbey International Concert Organist Durham Cathedral Liverpool Cathedral Paul Hale was Cathedral Organist John Scott Whiteley is Organist Peter King was Director of Music at Gordon Stewart was born in Daniel Cook is Master of the Professor Ian Tracey has had a and Rector Chori at Southwell Minster Emeritus of York Minster and well Bath Abbey from 1986-2016 and where Scotland and studied at the Royal Choristers and Organist of Durham life-long association with Liverpool Manchester College of Music and the for twenty seven years and appointed known for his performances of the he is now Organist Emeritus. In 1997 Cathedral where he began his music Cathedral becoming the youngest Geneva Conservatoire gaining a cathedral organist in the country in Organist Emeritus following his complete organ works of Bach on BBC he established a girls' choir which education before spending a year as retirement. He was previously Assistant television. He studied with Ralph Performer’s Diploma with distinction in Organ Scholar at Worcester Cathedral. 1980. After 27 years in post the Dean quickly became one of the finest in the Manchester and a Premier Prix de Organist of Rochester Cathedral, Downes at the Royal College of Music From there he took up a place at the and Chapter created the post of country. Described as 'a virtuoso of Virtuosité in Geneva. A former Organist Organist Titulaire allowing him the Organist of Tonbridge School and and with Fernando Germani and Flor of Manchester and Blackburn Royal Academy of Music studying world class' he has an extensive and freedom to devote more time to Organ Scholar of New College, Oxford. -

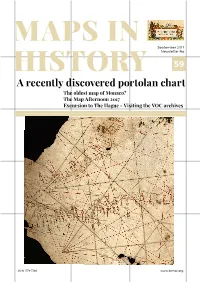

A Recently Discovered Portolan Chart the Oldest Map of Monaco? the Map Afternoon 2017 Excursion to the Hague - Visiting the VOC Archives

MAPS IN September 2017 Newsletter No HISTORY 59 A recently discovered portolan chart The oldest map of Monaco? The Map Afternoon 2017 Excursion to The Hague - Visiting the VOC archives ISSN 1379-3306 www.bimcc.org 2 SPONSORS EDITORIAL 3 Contents Intro Dear Map Friends, Exhibitions Paulus In this issue we are happy to present not one, but two Aventuriers des mers (Sea adventurers) ...............................................4 scoops about new map discoveries. Swaen First Joseph Schirò (from the Malta Map Society) Looks at Books reports on an album of 148 manuscript city plans dating from the end of the 17th century, which he has Internet Map Auctions Finding the North and other secrets of orientation of the found in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Of course, travellers of the past ..................................................................................................... 7 in Munich, Marianne Reuter had already analysed this album thoroughly, but we thought it would be March - May - September - November Orbis Disciplinae - Tributes to Patrick Gautier Dalché ... 9 appropriate to call the attention of all map lovers to Maps, Globes, Views, Mapping Asia Minor. German orientalism in the field it, since it includes plans from all over Europe, from Atlases, Prints (1835-1895) ............................................................................................................................ 12 Flanders to the Mediterranean. Among these, a curious SCANNING - GEOREFERENCING plan of the rock of Monaco has caught the attention of Catalogue on: AND DIGITISING OF OLD MAPS Rod Lyon who is thus completing the inventory of plans www.swaen.com History and Cartography of Monaco which he published here a few years ago. [email protected] The discovery of the earliest known map of Monaco The other remarkable find is that of a portolan chart, (c.1589) ..........................................................................................................................................15 hitherto gone unnoticed in the Archives in Avignon. -

John Hendrix Keywords Architecture As Cosmology

John Hendrix Keywords Architecture as Cosmology: Lincoln Cathedral and English Gothic Architecture architecture, cosmology, Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln Academy, English Gothic Architecture, Robert Grosseteste (Commentary on the Physics, Commentary on the Posterior Analytics, Computus Correctorius, Computus Minor, De Artibus Liberalibus, De Calore Solis, De Colore, De Generatione Sonorum, De Generatione Stellarum, De Impressionibus Elementorum, De Iride, De Libero Arbitrio, De Lineis, De Luce, De Motu Corporali at Luce, De Motu Supercaelestium, De Natura Locorum, De Sphaera, Ecclesia Sancta, Epistolae, Hexaemeron), medieval, University of Lincoln, Early English, Decorated, Curvilinear, Perpendicular, Catholic, Durham Cathedral, Canterbury Cathedral, Anselm of Canterbury, Gervase of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, Becket’s Crown, Trinity Chapel, Scholasticism, William of Sens, William the Englishman, Geoffrey de Noyers, Saint Hugh of Avalon, Saint Hugh’s Choir, Bishop’s Eye, Dean’s Eye, Nikolaus Pevsner (Buildings of England, Cathedrals of England, Leaves of Southwell, An Outline of European Architecture), Paul Frankl (Gothic Architecture), Oxford University, Franciscan School, Plato (Republic, Timaeus), Aristotle (De anima, De Caelo, Metaphysics, Physics, Posterior Analytics), Plotinus (Enneads), Wells Cathedral, Ely Cathedral, Hereford Cathedral, Lichfield Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral, Beverley Minster, Chester Cathedral, York Minster, Worcester Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, Southwell Minster, Gloucester Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, Elias -

The Taste of Legends Baltic Outlook Journalists Natali Lekka and Chris Yeomans Visit Nottinghamshire in Search of History, Legend and Culinary Delights

OUTLOOK / TRAVEL The taste of legends Baltic Outlook journalists Natali Lekka and Chris Yeomans visit Nottinghamshire in search of history, legend and culinary delights. TEXT BY NATALI LEKKA AND CHRIS YEOMANS PHOTOS COURTESY OF EXPERIENCE NOTTINGHAMSHIRE AND VISITENGLAND Fly to Europe with airBaltic ONE from €29 WAY Newark Market he English county of Nottinghamshire is reminder of the country’s sometimes violent past. steeped in history and legend. From the In 2015, Newark plans to open a National Civil War famous Robin Hood to numerous kings and Museum devoted to this key event in English history. lords, many have traversed and left their mark. One of the most striking things about Newark-on- TToday’s visitors can get there much faster than the Trent is the large number of independent retailers and horses and carriages of medieval times, and our easterly restaurants, giving the high street a more bespoke starting point of Newark-on-Trent is only one hour and nature than in other market towns of a similar size. 15 minutes by train from London’s King’s Cross station. Known as a foodie’s paradise, Newark has restaurants The bustling market town of Newark brims with tales that cater to all appetites and budgets. Our first from yesteryear, and it has played a notable part in two culinary stop was at Gannet’s Day Café, a family-owned of the most significant wars in English history. During bistro housed in an elegant Georgian building near the the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487), King Edward IV of castle.