Forest Certification Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Jack Buckley, Director

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Jack Buckley, Director June 16, 2015 Eammon Coughlin, Planner Berkshire Regional Planning Commission 1 Fenn Street, Suite 201 Pittsfield, MA 01201 Re: Open Space Plan; 98-3310 Town of Lee Dear Mr. Coughlin: Thank you for contacting the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP) regarding the update for the Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Lee. A letter was previously prepared for Lee in 1998 and this serves as an update to that letter. Enclosed is information on the rare species, priority natural communities, vernal pools, and other aspects of biodiversity that we have documented in Lee. The town is encouraged to include this letter, species list, appropriate maps, and the BioMap2 town report in the Open Space and Recreation Plan. Based on the BioMap2 analysis and additional information discussed below, NHESP recommends land protection in the BioMap2 cores or protecting lands adjacent to existing conservation land – or, best, a combination of both when feasible. All of the areas discussed below are important for biodiversity protection in Lee. Land adjacent to the Cold Water Fisheries is also important Enclosed is a list of rare species and natural communities known to occur or have occurred in Lee. This list and the list in BioMap2 differ because this list and discussion include all of the uncommon aspects of biodiversity in Lee that NHESP has documented and BioMap2 focused on occurrences with state-wide significance and included non-MESA listed species of conservation interest from the State Wildlife Action Plan. In addition, the NHESP database is constantly updated and the enclosed list may include species of conservation interest identified in town since BioMap2 was produced in 2010. -

Continuous Forest Inventory 2014

Manual for Continuous Forest Inventory Field Procedures Bureau of Forestry Division of State Parks and Recreation February 2014 Massachusetts Department Conservation and Recreation Manual for Continuous Forest Inventory Field Procedures Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation February, 2014 Preface The purpose of this manual is to provide individuals involved in collecting continuous forest inventory data on land administered by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation with clear instructions for carrying out their work. This manual was first published in 1959. It has undergone minor revisions in 1960, 1961, 1964 and 1979, and 2013. Major revisions were made in April, 1968, September, 1978 and March, 1998. This manual is a minor revision of the March, 1998 version and an update of the April 2010 printing. TABLE OF CONTENTS Plot Location and Establishment The Crew 3 Equipment 3 Location of Established Plots 4 The Field Book 4 New CFI Plot Location 4 Establishing a Starting Point 4 The Route 5 Traveling the Route to the Plot 5 Establishing the Plot Center 5 Establishing the Witness Trees 6 Monumentation 7 Establishing the Plot Perimeter 8 Tree Data General 11 Tree Number 11 Azimuth 12 Distance 12 Tree Species 12-13 Diameter Breast Height 13-15 Tree Status 16 Product 17 Sawlog Height 18 Sawlog Percent Soundness 18 Bole Height 19 Bole Percent Soundness 21 Management Potential 21 Sawlog Tree Grade 23 Hardwood Tree Grade 23 Eastern White Pine Tree Grade 24 Quality Determinant 25 Crown Class 26 Mechanical Loss -

Town of Erving

Design Alternatives for the Reuse of USHER MILLS Prepared for Town of Erving 12 East Main Street Index Erving, MA 01344 INTRODUCTION AND GOALS 1 CONTEXT 2 CONTEXT-HISTORY 3 BROWNFIELD DESIGNATION 4 EXISTING CONDITIONS 5 EXISTING CONDITIONS CROSS SECTION 6 ACCESS, CIRCULATION, AND RARE SPECIES 7 LEGAL ANALYSIS 8 SUMMARY ANALYSIS 9 COMMON ELEMENTS OF DESIGN ALTERNATIVES 10 DESIGN ALTERNATIVE #1 11 DESIGN ALTERNATIVE #2 12 DESIGN ALTERNATIVE #3 13 DESIGN ALTERNATIVE #4 14 DESIGN PRECEDENTS ALTERNATIVES #1 & #2 15 DESIGN PRECEDENTS ALTERNATIVES #3 & #4 16 PROPOSED PLANT PALETTE 17 RECOMMENDATIONS 18 Design Alternatives for the Reuse of Karen H. Dunn FALL 2010 Karen H. Dunn, FALL 2010 USHER MILLS Conway School of Landscape Design1 Conway School of Landscape Design Town of Erving 332 South Deerfield Road, Conway, MA 01341 12 E Main Street, Erving, MA 01344 332 South Deerfield Road, Conway, MA 1801341 NOT FOR CONSTRUCTION. THIS DRAWING IS PART OF A STUDENT PROJECT AND IS NOT BASED ON A LEGAL SURVEY. All of the Usher Mills project goals are in harmony with the goals and objectives of the Town of Erving 2002 Master Plan and the 2010 Open Space and Recreation Plan. These guides provide a framework for decisions dealing with land uses that may impact valuable natural resources and the lands that contain unique historical, recreational, and scenic values. Goals and objectives of the two plans that relate to the Usher Mills site include • Prioritize Town-sponsored land protection projects that conserve forestland, drinking water, streams and ponds, open fields, scenic views, wildlife habitat, river access and wetlands. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Massachusetts Forests at the Crossroads

MASSACHUSETTS FORESTS AT THE CROSSROADS Forests, Parks, Landscapes, Environment, Quality of Life, Communities and Economy Threatened by Industrial Scale Logging & Biomass Power Deerfield River, Mohawk Trail Windsor State Forest, 2008, “Drinking Water Supply Area, Please protect it!” March 5, 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The fate of Massachusetts’ forests is at a crossroads. Taxpayer subsidized policies and proposals enacted and promoted by Governor Patrick’s office of Energy and Environmental Affairs seriously threaten the health, integrity and peaceful existence of Massachusetts forests. All the benefits provided by these forests including wilderness protection, fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, clean water, clean air, tourism, carbon sequestration and scenic beauty are now under threat from proposals to aggressively log parks and forests as outlined below. • About 80% of State forests and parks are slated for logging with only 20% set aside in reserves. (p.4) • Aggressive logging and clear-cutting of State forests and parks has already started and new management plans call for logging rates more than 400% higher than average historical levels. (p. 5-18) • “Clear-cutting and its variants” is proposed for 74% of the logging. Historically, selective logging was common. (p. 5-18) • The timber program costs outweigh its revenue . Taxpayers are paying to cut their own forests.(p.19) • The State has enacted laws and is spending taxpayer money devoted to “green” energy to promote and subsidize the development of at least five wood-fueled, industrial-scale biomass power plants. These plants would require tripling the logging rate on all Massachusetts forests, public and private. At this rate, all forests could be logged in just 25 years. -

Singletracks #85 May 2006

NEMBAFest ~ June 11th ~ MTB Festival SSingleingleTTrackrackSS MayMay 2006,2006, NumberNumber 8585 www.nemba.orgwww.nemba.org GGoooodd OOlldd DDaayyss ooff FFrreeeerriiddiinngg Hey,Hey, Hey...Hey... MaahMaah DaahDaah Hey!Hey! NEMBA’sNEMBA’s MondoMondo EventsEvents CalendarCalendar 100s100s ofof Rides,Rides, TonsTons ofof EventsEvents SoSo littlelittle time,time, soso muchmuch toto do!do! WHEELWORKS THANKS our CUSTOMERS and VENDORS for recognizing our commitment to CYCLING. Visit us: March 31- April 5 AS The Original SuperSale kicks off the cycling season! SSingleingleTTrackS NEMBA, the New England Mountain Bike May 2006, Number 85 Association, is a non-profit 501 (c) (3) organi- zation dedicated to promoting trail access, maintaining trails open for mountain bicyclists, and educating mountain bicyclists to use these trails sensitively and responsibly. Hey, Hey... SingleTracks is published six times a year by the New England Mountain Bike Association for the trail community. Maah Daah ©SingleTracks Editor & Publisher: Philip Keyes Hey 16 Contributing Writer: Jeff Cutler Copy Editor: Nanyee Keyes Singletrack heaven snaking across North Dakota Executive Director: Philip Keyes makes for a great singlespeed adventure. By [email protected] Alexis Arapoff NEMBA PO Box 2221 Acton MA 01720 Good Old Voice 800.57.NEMBA Fax: 717-326-8243 [email protected] Days of Board of Directors Freeriding 21 Tom Grimble, President Bill Boles, Vice-President Anne Shepard, Treasurer Tom Masterson,1990 masters cyclocross champion, Tina Hopkins, Secretary reminisces about the early days of freeriding and why they got him to start his own mountain bike camp for young Rob Adair, White Mountains NEMBA and old. By Tom Masterson Norman Blanchette, MV NEMBA Todd Bumen, Mt. -

Singletracks #91 May 2007

Ride it like you mean it! SSingleingleTTrackrackSS MayMay 2007,2007, NumberNumber 9191 www.nemba.orgwww.nemba.org SSingleingleTTrackS NEMBA, the New England Mountain Bike May 2007, Number 91 Association, is a non-profit 501 (c) (3) organi- zation dedicated to promoting trail access, maintaining trails open for mountain bicyclists, and educating mountain bicyclists to use these trails sensitively and responsibly. 29ers SingleTracks is published six times a year by the Fad or fantastic? What’s behind the new craze to ride New England Mountain Bike Association for bigger wheels? Maybe one should be in your quiver of the trail community. bikes! By Brendan Dee 12 ©SingleTracks Editor & Publisher: Philip Keyes 17 Contributing Writer: Jeff Cutler Copy Editor: Nanyee Keyes Executive Director: Philip Keyes Riding Gooseberry [email protected] NEMBA Mesa PO Box 2221 Acton MA 01720 A stone’s throw from Zion National Park, Gooseberry offers Moab-like slickroad with to-die-for vistas. By John Isch Voice 800.57.NEMBA Fax: 717-326-8243 [email protected] Board of Directors 22 Bear Brook and Case Tom Grimble, President Harold Green, Vice-President Anne Shepard, Treasurer Mountain Tina Williams, Secretary Looking for a couple of great places to explore? New Hampshires’ Bear Brook State Park and Connecticut’s Case Rob Adair, White Mountains NEMBA Norman Blanchette, MV NEMBA Mountain should be high on your list. Todd Bumen, Mt. Agamenticus NEMBA Bob Caporaso, CT NEMBA Jon Conti, White Mountains NEMBA Peter DeSantis, Seacoast NEMBA SingleTracks Hey, get creative! We wel- John Dudek, PV NEMBA come submissions, photos and artwork. This is Bob Giunta, Merrimack Valley NEMBA your forum and your magazine. -

Baker-Polito Administration Announces Temporary Closure of Certain State Conservation and Recreation Managed Facilities

E M E R G E N C Y A L E RT S Coronavirus Update SHOW ALERTS Mass.gov PRESS RELEASE Baker-Polito Administration Announces Temporary Closure of Certain State Conservation and Recreation Managed Facilities FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 3/13/2020 Department of Conservation & Recreation MEDIA CONTACT Olivia Dorrance, Press Secretary Phone (617) 626-4967 (tel:6176264967) Online [email protected] (mailto:[email protected]) BOSTON - Out of an abundance of caution due to the spread of COVID-19 in Massachusetts, the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has announced the temporary closure of certain agency managed facilities effective Saturday, March 14, 2020 through Wednesday, April 1, 2020 at which time DCR will reassess circumstances. Additionally, during the temporary closure all associated events at these locations are cancelled. Importantly, all state parks and comfort stations across the Commonwealth remain open and available for the public to utilize. DCR reminds residents and visitors to avoid gathering in large groups, maintain social distancing, and practice healthy personal hygiene to stop the spread of the virus. The temproary closures of certain facilities is consistent with the State of Emergency declared (/news/governor-baker-declares-state-of-emergency-to-support-commonwealths-response-to-coronavirus) by Governor Baker on Tuesday, March 10, 2020 and guidance that conferences, seminars and other discretionary gatherings, scheduled and hosted by Executive Branch agencies involving external parties are to be held virtually or cancelled. Additionally, Governor Charlie Baker issued (/news/governor-baker-issues-order-limiting-large-gatherings-in-the-commonwealth) an emergency order prohibiting most gatherings of over 250 people to limit the spread of the COVID-19. -

Report on the Real Property Owned and Leased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office for Administration and Finance Report on the Real Property Owned and Leased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Published February 15, 2019 Prepared by the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance Carol W. Gladstone, Commissioner This page was intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Report Organization 5 Table 1 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office 11 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 2 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by County 17 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 3 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office and Agency 23 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 4 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Site and Municipality 85 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 5 Commonwealth Active Lease Agreements by Municipality 303 Private leases through DCAMM on behalf of state agencies APPENDICES Appendix I Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office 311 Version of Table 1 above but for State-owned only (excludes Authorities) Appendix II County-Owned Buildings Occupied by Sheriffs and the Trial Court 319 Appendix III List of Conservation/Agricultural/Easements Held by the Commonwealth 323 Appendix IV Data Sources 381 Appendix V Glossary of Terms 385 Appendix VI Municipality Associated Counties Index Key 393 3 This page was intentionally left blank. -

Singletracks #104 July 2009

JulyJuly 20092009 #104#104 www.nemba.orgwww.nemba.org Great Places to Ride SSingleingleTTrackS NEMBA, the New England Mountain Bike July 2009, Number 104 Association, is a non-profit 501 (c) (3) organi- zation dedicated to promoting trail access, maintaining trails open for mountain bicyclists, and educating mountain bicyclists to use these trails sensitively and responsibly. Wendell State SingleTracks is published six times a year by the New England Mountain Bike Association for Forest the trail community. ©SingleTracks 10 Editor & Publisher: Philip Keyes Contributing Writer: Jeff Cutler Copy Editor: Nanyee Keyes Executive Director: Philip Keyes [email protected] Pachaug NEMBA PO Box 2221 State Park Acton MA 01720 13 Voice 800.57.NEMBA Fax: 717-326-8243 [email protected] Board of Directors Harold Green, President Fresh Singletrack at Peter DeSantis, Vice-President Anne Shepard, Treasurer Tom Grimble, Secretary Russell Mill 16 Rob Adair, White Mountains NEMBA Brian Alexander, CeMeNEMBA John Anders, Midcoast Maine NEMBA Brian Beneski, CeMeNEMBA Norman Blanchette, MV NEMBA Matt Bowser, Central NH NEMBA Matt Caron, Southern NH NEMBA Steve Cobble, SE MA NEMBA SingleTracks Hey, get creative! We wel- Jon Conti, White Mountains NEMBA come submissions, photos and artwork. This is Eammon Carleton, BV NEMBA Leo Corrigan, RI NEMBA your forum and your magazine. Be nice, and Kevin Davis, Midcoast Maine NEMBA share! Peter DeSantis, Southern NH NEMBA On the Cover: Elizabeth Pell at Opening Day at Bob Giunta, MV NEMBA Paper Trail Brad Herder, Berkshire NEMBA the Middlesex Fells. Photo by Philip Keyes Rich Higgins, SE MA NEMBA Have a pic that would make a good cover shot? Steve LaFlame, Central NH NEMBA NEMBA Calendar — 4 Email it to [email protected] Frank Lane, NS NEMBA Treadlines — 5 Casey Leonard, Midcoast Maine NEMBA Want to Underwrite in ST? Eric Mayhew, CT NEMBA SideTracks — 23 Liam O’Brien, PV NEMBA SingleTracks offers inexpensive and targeted Tim Post, GB NEMBA Basic Biking — 18 underwriting which helps us defray the cost of Matt Schulde, RI NEMBA producing this cool ‘zine. -

MASTER HHT Facility Information

Department of Conservation and Recreation Healthy Heart Trails Location Information ADA Facility Name Name of Trail Surface Accessible Lenth of Trail Activity Level Starting Point Ashuwillticook Rail Trail Ashuwillticook Rail Trail Paved Yes 11 miles Easy Berkshire Mall Rd. Park at Lanesboro/Discover Berkshire Visitor Center-Depot St., Adams Beartown State Forest Benedict Pond Loop Trail Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Easy Boat Ramp Parking Area at Benedict Pond Beaver Brook Loop starting in main parking lot Partially Paved yes .75 Miles Easy Start at Main parking Lot Beaver Brook Reservation Beaver Brook Loop Partially Paved Yes .75 Miles Easy Begins at the main parking area on waverly Oaks Rd. in Waltham Belle Isle Marsh Reservation Belle Isle Meadow Loop Unpaved Yes 0.6 Miles Easy Start at the main parking lot off Bennington Street, East Boston Blackstone River & Canal HSP Blackstone Canal Towpath Trail Unpaved No 1 Mile Easy Tri River Health Center Parking Lot Borderland State Park Part of Pond Walk Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Easy Visitor's Center Bradley Palmer State Park Interpretive Trails #46 and #2 Unpaved No 1.2 Miles Easy Interpretive Trail #46 behind the Headquarters Building trail begins off main parking lot near visitor center Breakheart Reservation (fox run trail to Saugus River trail) Unpaved 1.4 Miles Moderate Breakheart Visitor Center Callahan State Park Backpacker/Acorn Trail Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Moderate Broad Meadow Parking Lot Castle Island Castle Island Loop Paved Yes .75 Miles Easy At the junction of the playground and main path Charles River Esplanade Esplanade Loop Paved Yes 1.5 Miles Easy Path begins at the Lee Pool Parking Lot Chestnut Hill Reservation Reservoir Loop Unpaved Yes 1.5 Miles Easy Start at the bulletin board on Beacon Street near the skating rink Chicopee Memorial State Park Loop Trail Paved Yes 2.4 Miles Easy Base of the Recreation Area Parking Lot Cochituate State Park Snake Brook Trail Unpaved Yes 1.5 Miles Moderate Rt 27 in Wayland. -

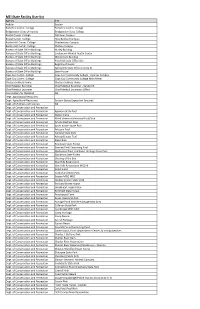

MEI State Facilities Inventory List.Xlsx

MEI State Facility User list Agency Site Auditor Boston Berkshire Comm. College Berkshire Comm. College Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State College Bristol Comm. College Fall River Campus Bristol Comm. College New Bedford Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Charlestown Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Chelsea Campus Bureau of State Office Buildings Hurley Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Lindemann Mental Health Center Bureau of State Office Buildings McCormack Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Pittsfield State Office Site Bureau of State Office Buildings Registry of Deeds Bureau of State Office Buildings Springfield State Office Liberty St Bureau of State Office Buildings State House Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College ‐ Hyannis Campus Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College Main Meter Chelsea Soldiers Home Chelsea Soldiers Home Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiner ‐ Sandwich Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiners Office Commission for the Blind NA Dept. Agricultural Resources Dept. Agricultural Resources Eastern States Exposition Grounds Dept. of Children and Families NA Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Agawam State Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Aleixo Arena Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Allied Veterans Memorial Pool/Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Amelia Eairhart Dam Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ames Nowell State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Artesani Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashland State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashuwillticook Trail Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bajko Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Beartown State Forest Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bennett Field Swimming Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park Dept.